Unit 2. Managing Data

J Toby Mordkoff and Leyre Castro

Summary. This unit discusses the distinction between raw data and the pre-processed values that are used for the subsequent analysis. The various formats and rules with regard to managing and storing data are also reviewed.

Prerequisite Units

Unit 1. Introduction to Statistics for Psychological Science

Psychological Data

Psychology is an empirical science. This means that psychological theories are tested by comparing their predictions to actual observations, which are often referred to as data. If the data match the predictions, the theory survives; if the data fail to confirm the predictions, the theory is falsified (which is a fancy way of saying disproved). Because of their crucial role, psychological data must be handled carefully and treated with respect. They must be organized and stored in a logical and standardized manner and format, allowing for their free exchange between researchers. One useful saying that summarizes empirical science is that “while researchers are encouraged to argue about theory, everyone must agree on the data.”

In some (very rare) instances, the relevant data are quite simple, such as a single yes-or-no answer to one question that was asked of a sample of people. In such a case, a list of the yes or no responses would be sufficient. Usually, however, quite a lot of information is gathered from each participant. For example, besides an answer to a yes-or-no question, certain demographic information (e.g., age, sex,, etc.) might also be collected. Alternatively, maybe a series of questions are asked. Or the questions might require more complicated responses, which could be numerical (e.g., “on a scale of 1 to 10, how attractive do you find this person to be?”) or qualitative (e.g., “what is your favorite color?”). Or maybe the participant is asked to perform a task many times, instead of just once, with multiple pieces of information (e.g., response time and response choice) recorded on every, separate trial.

The variety and potential complexity of psychological data raises at least two issues. One issue concerns the storage of data: should all of the data from every participant be stored together in one file or should the data from each participant be stored separately? Another issue concerns the distinction between what can be called “raw data” – which are the individual observations as they were originally collected – and “pre-processed data” (or “data after pre-processing”) – which are the values that will be used for the formal analysis.

Pre-processing Data

Starting with the second issue, imagine an experiment in which participants must press the left button if the stimulus is blue and the right button if the stimulus is orange. The location of the stimulus is irrelevant – only the color matters – but sometimes the stimulus appears on the left and sometimes it appears on the right. (This task is based on work by J. Richard Simon of the University of Iowa, starting in the 1960s.) The participants are asked to respond as quickly as possible while making very few errors.

In such an experiment, it is typical for each of the four possible combinations of stimulus color and stimulus location to be used on a very large number of trials (e.g., 50 or more of each). Thus, the “raw data” from a single participant would be hundreds of sets of stimulus conditions (color and location) with multiple response values (which button was pressed and how long was required to make the response). But the analysis would not concern these individual sets of trial observations; instead, the raw data would be converted to a small number of summary scores (see Unit 1), such as average response time and percent correct for each of the four combinations of stimulus color and stimulus location.

Note that averaging is not the only change to the data that might occur during pre-processing. In the above example, the raw data were recorded in terms of stimulus color (blue vs orange), stimulus location (left vs right), response time (in milliseconds), and which response was made. During pre-processing, the stimulus locations might be re-coded in terms of whether the stimulus appeared near the correct response for the trial (which is often referred to as “congruent” or “compatible”) or on the opposite side (“incongruent” or “incompatible”), because that is what most theories predict to be important. Likewise, the value of which response was made would be converted to whether the response was correct. In other words, pre-processing in this case is doing two things: it is taking a huge number of pieces of raw data and reducing it down to just a few summary scores, and it is converting the data from the format of the events during the experiment to the format about which the theories make predictions.

Another example of pre-processing occurs when a long questionnaire is used to measure a small number of psychological constructs, such as measures of depression and anxiety. This often requires that participants provide ratings (e.g., on a 7-point scale) of how well each of many different statements (e.g., “I often feel sad” or “I’m often quite worried”) applies to them. In this case, the raw data are the individual ratings for each of the questions, but what is needed for the analysis are the condensed scores for each of the small number of constructs. During pre-processing, each participant’s answers to many questions are somehow combined to create these values, and then these are what are used for the actual analysis.

Pre-processing Data vs Analyzing Data

The key to the distinction between pre-processing data and subsequent analysis is best thought about in terms of why each is done. The purpose of pre-processing is to convert the raw data into the format for which the relevant theories make predictions. Pre-processing also simplifies matters by reducing the total number of pieces of data. Note that the theories are not yet being tested; the data are only being prepared for the subsequent test. For example, very few theories make predictions about response times on individual trials; they make predictions about average response time, instead. If the theories did make predictions about individual trials, then the raw data would not be pre-processed; they’d be left as individual response times.

Likewise, few theories make predictions about the answers a participant might give to a single, specific question, such as “how often do you skip breakfast?”; they make predictions about the underlying psychological construct, such as depression. As above, pre-processing the numerous, separate answers into one or two measures of psychological constructs is not only simplifying the data by reducing the number of values to be analyzed, it is also converting the data into the form that matches the theory.

File Formats

In both examples in the previous section, pre-processing produces a small number of values from a very large amount of raw data. This brings us to the second issue raised above: how many files should be used? To answer this question, we need to discuss the various formats for files.

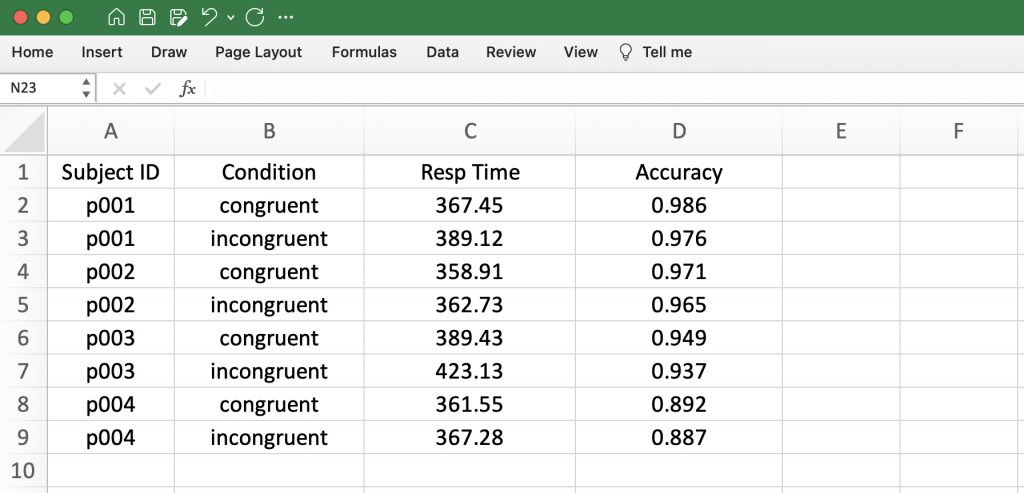

Psychological data are usually stored in large tables, often referred to as “spreadsheets,” which can be viewed and edited using various software packages, such as Excel. (All of the pictures below are screen-shots of parts of Excel spreadsheets.) Although the details of these tables vary considerably, they all obey one simple rule: each column in a spreadsheet always contains a single, specific piece of information, which does not change across rows, and each usually has a header (i.e., a special top row) that indicates what exactly is in every box in the column.

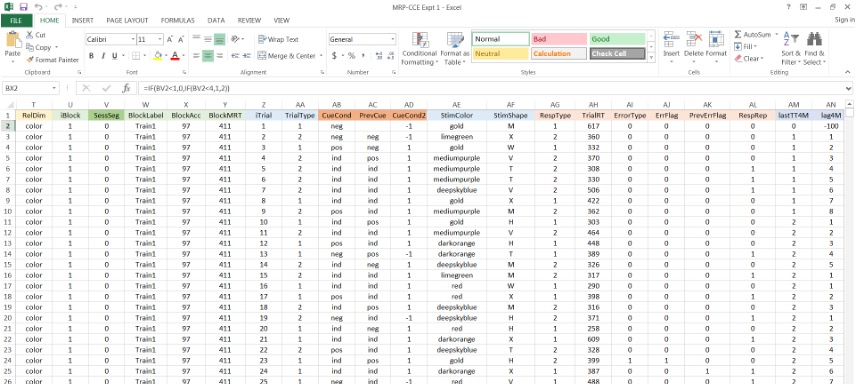

In the case of a response-time experiment, the raw data are usually produced by the software that runs the experiment, with each participant’s data in a separate file. A complicated example of this was provided at the beginning of this unit; a much simpler example that matches the experiment from above is provided in Figure 2.1:

Note how each column has a label value in the first row, while each subsequent row contains the information related to a single trial. You know this, because the first column tells you how the rows are defines. It is standard good practice to do this: have the first column in the spreadsheet specify what is contained in each row. In general, the raw data from a response-time experiment will use this format. From these data, the summary values would be calculated – repeated for each participant, separately – and then these calculated values would placed in a new file that uses a different format:

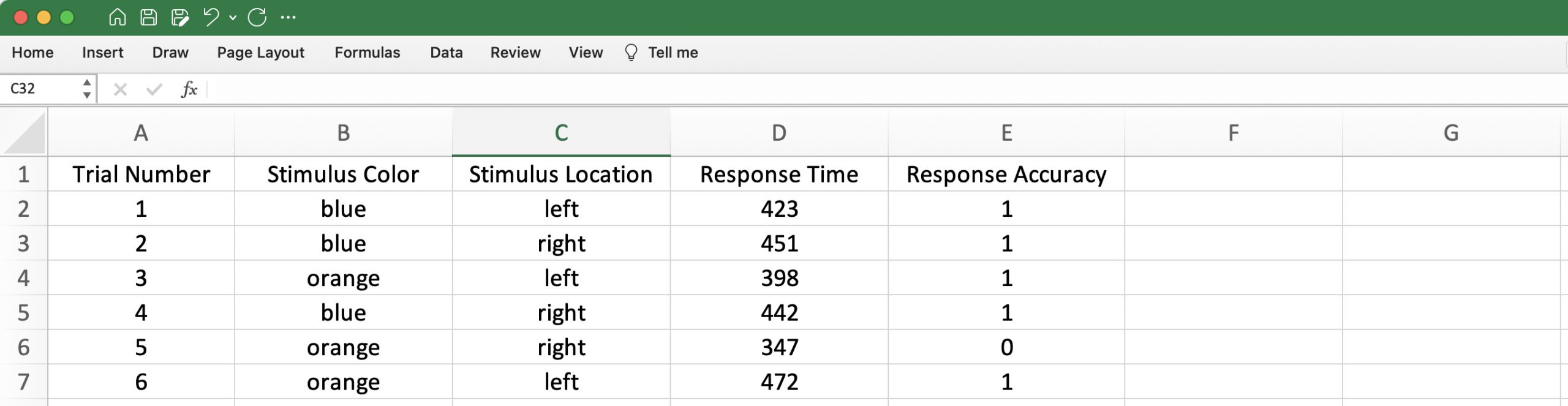

As was true the raw-data files, each column in this sheet contains a specific piece of information, as indicated by the header row at the top. In contrast to the separate files for each participant, in which each subsequent row was a trial, in this file, each row holds the data for a particular participant. This is the standard format for the data that will be used for the actual analysis: each participant gets a row in the spreadsheet.

Wide vs Long Format

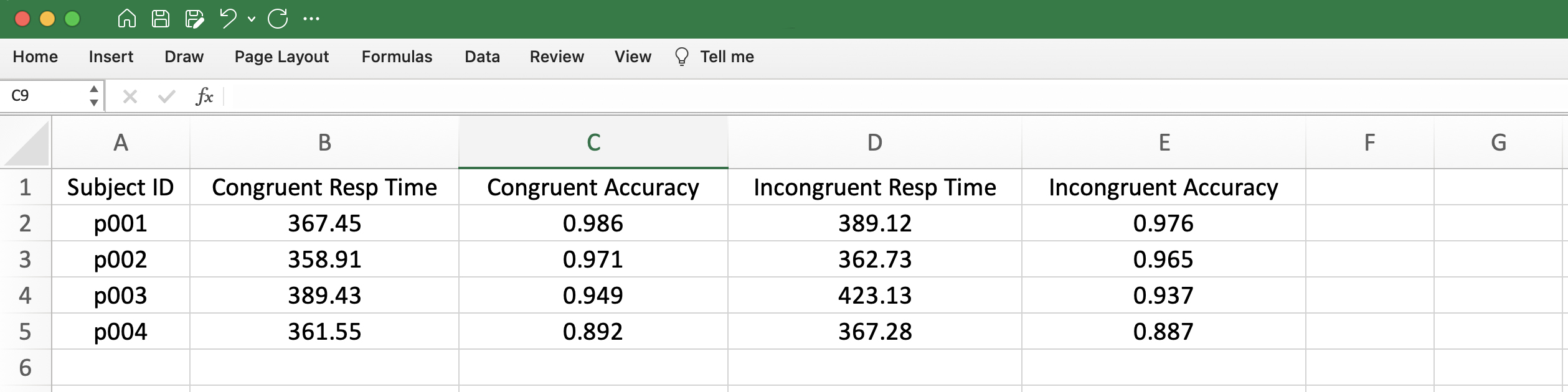

The technical label for a file that places all of the values for each participant on one (and only one) row is “wide format,” because these spreadsheets can often have a very large number of columns. This is the standard in psychology. An alternative format uses multiple rows for each participant, with some columns being used to indicate the condition(s) under which the subset of the data were collected. This is known as “long format.” Here is an example using the same values as previously, but now in long format:

Long format is rarely used and the software packages that still employ this format for certain analyses usually have a built-in procedure for converting one format to the other. For this reason, and to maintain consistency, psychological data are almost always stored in wide format.

In contrast to response-time experiments, in which each participant performs hundreds of trials and separate files are used for each participant’s raw data, all of the data from a questionnaire study is usually stored in one file. These files use the wide format: each item on the questionnaire gets a separate column, each participant get one row, and the first row in the file provides the label for each of the columns. When condensed scores are calculated (e.g., a measure of depression) based on the raw data in several columns, these can be added to the same file as a new, separate column, or placed in a new file that holds only the values that are needed for the subsequent analysis.

Data Storage

Before anything else, here is the cardinal rule: never throw any information away; keep all of the raw data, even if you don’t currently have a need or use for them. There are two main reasons for this: first, you might discover a use for these data later; second, someone else might already have a use for them. (It might also appear a bit suspicious if you collect certain data and then delete them, making them unavailable to others who might ask about them.)

This rule applies to all of the data as originally collected. If, for example, you omit a few trials of a response-time experiment during pre-processing, maybe because the response was abnormally fast or slow (i.e., an outlier), you do not delete the trial from the raw-data file; you merely skip over it during pre-processing. Likewise, if you decide to omit all of the data from a certain participant, maybe because they did not appear to follow instructions, you still keep the file that holds their raw data; you just don’t include their values in the file for subsequent analysis.

In situations where you have large amounts of raw data, such as response-time experiments or long questionnaires, the files that contain the raw data can stored separately from the single, small file that holds the pre-processed values that are ready for analysis. As discussed above, the raw-data files might use a format that is different from the final file – that is fine, as long as the header row in every file makes it clear what’s contained in each column. If condensed scores were added to a raw-data file, as is often done with questionnaire data, you can save two versions, if you wish: one with everything and another with only the final values that are needed for the analysis – that, also, is fine, as long as keep all of the raw data somewhere.

Set of observations representing the values of the variables under study (singular: datum; plural: data).

A variable whose values are indicated by numbers.

A variable whose values do not represent an amount of something; rather, they represent a quality. Also called categorical variable.

A research study in which the researcher manipulates one or more variables (independent variables) and then measures one or more other variables (dependent variables). In an experiment, there is at least one independent variable and at least one dependent variable.