23 Projects

Narrative Ethnography

Heartbeat

exhaustion from the long drive from Minneapolis, we headed down the stairs to dream of sugar

plums.

I woke up to the quiet hum of a toothbrush. As I moved to get up my body ached and groaned. I made my way slowly shifting to the open doorway. I looked in the mirror and saw golf balls sized bags under each eye, and a vampire complexion staring back at me. I slugged up the stairs and found a spot at the table. I must have picked up that cold Veronica had at work this week, I thought to myself. My mother-in-law took the chair across from me and sat down with her mug that read Everything’s Bigger in Texas. “Looks like someone’s not feeling well this morning.” She was clearly fishing for intel on the contents of my uterus. “I’m not pregnant, I know, I tested, It was negative,” I reply hoping that will end the interrogation. “If you say so,” she muttered, gazing toward the window, watching the small flecks of snow blowing in the wind. Christmas and New Year’s came and went, but I still had this awful cold. I sent Veronica an email asking her if she too had this long of an ailment. Her response was quite short:

Dear Karen,

No, but that’s how it was when I was pregnant with Max.

Take another test.

Love,

Your best friend who thinks you’re pregnant

I headed to the bathroom and stretched to reach the basket on the top shelf. I grabbed one frenemy from the box. By the time I reached the microwave to set the timer, there were already parallel blue lines. My heart skipped a beat. I’m pregnant…again…

Eight long weeks later

“Hello, checking in for Karen Smith.” I tried not to show my nervous excitement as I spoke. “Alright, you are checked in, please fill out this paperwork and give it to the doctor when she comes in.”

I found it odd that she did not have me state my birthdate. I go to this clinic all the time–well not this part of the clinic–-but they always ask. Maybe things run differently up here. I sat down next to Chris and could feel he was just as nervous as I was by the calmness of his hands. We were not sitting long before the nurse called us back to the room. I walked into a gallery of warning signs. The lists and lists of don’ts painted the walls, and armies of pamphlets littered the room with more cautionary tales. The nurse asked me a few questions, took my blood pressure, and left, leaving us to wait once more. My rising panic was

quickly interrupted by a knock at the door. A tall woman with long dark hair and twinkling eyes stepped in. She smiled as she sat down on the stool across from me. “Congratulations,” was the first word she spoke. She began asking question after question, going down what seemed like a never-ending list. After the interrogation, she set down her clipboard and spoke directly to us. “I do have a few higher-risk patients. However I might need to refer your case to another obstetrician, but we’ll

have to just wait and see how this all plays out.” This began an even longer conversation about what it meant to be a “geriatric pregnancy.” Chris squeezed my hand harder. She emphasized how we might need specialists and a different clinic, and I could feel my heart rate rising. I began spiraling at the thought of all the possible complications that could affect me or my baby. My heart was racing now. Was this normal for someone my age, 37, just two years into what is considered a “geriatric” pregnancy? I began zoning out, the world spinning around me, voices muffled as a high-pitched ring echoed in my head.

She paused suddenly, looking at me more intently. “Wait, how old are you again?” There was genuine curiosity in her voice. I was confused– shouldn’t that be in my chart? I have been coming to this clinic for over 10 years. “I’m 37,” I answered. She followed up, still puzzled. “So what year were you born?” Annoyance began to boil up under my skin, did this doctor not know how to do math? “I was born in 1966,” I replied plainly. “Ah,” she said, finally piecing it together. “I was trying to figure it out, your chart says you were born in 1956. I thought you did not look that old” I was momentarily frozen–not only was there an error in my chart, but this doctor had lectured me for hours and never bothered to check until the end of the visit. I began thinking back to how they never verified my age at check-in, and neither did the nurse nor the doctor. What should

have been an exciting first visit turned into a ball of perpetuating stress–not just because of one typo, but because of countless missed verification steps. The warmth of my husband’s hand grabbing mine snapped me out of my mental whirlwind. “….So, you can forget all that about specialists and switching clinics and such. Barring any major complication none of that will be necessary. I will have the nurse update your chart.

An awkward silence filled the air. I was waiting for an explanation for how this happened or at the very least, an apology for the stress she caused. But neither came. “So…what do you say, shall we get a listen here” her voice still a bit shaken. She grabbed a white box out of the cabinet next to the door. She grabbed a tube and squirted a generous amount of gel onto the wand. The liquid began dripping as she placed it on my stomach. The slimy cool wand glided across my flushed skin. The doctor’s smile faded as the seconds grew to minutes. My thoughts began to wander out of control. Maybe I am too old to be pregnant, maybe I’m not good enough to be a mother, maybe I’m the problem… Suddenly the machine noises changed from whooshing and swishing to a recognizable lub dub. At that moment, my worries quieted, replaced by the gentle rhythm of hope.

A heartbeat.

Creative Project

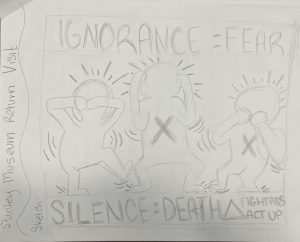

I enjoyed our visit to the Stanley Museum and was looking for a way to make the time to return. I decided to go in search of art that represents/resonates with my original topic for this project, eating disorders. However, as I was walking around the exhibit about Keith Haring interested me greatly. I found this beautiful poster that he had done (that I have attempted to sketch above) and knew that I wanted to dive into this piece and the topic of AIDS/HIV. I had very little knowledge about Keith Haring going into this exhibit other than a fellowship I was looking at as a possibility after grad school that was dedicated to him. When I first sat down it was obvious the issue I was exploring was written on the poster. This artistic poster was a gorgeous piece addressing the AIDS Epidemic and calling for change, through discussion and education. The artwork used the acclaimed pink triangle that was originally used as a marker by the Nazis for those who were believed to be homosexuals. This same pink color was used to make x’s on the 3 individuals representing that they had been “marked” by the disease. Also as I was sketching I was paying more attention to the hand placement of the individuals and noticed that they were representing see, hear, and speak no evil. I interpreted this as calling attention to those who are avoiding the AIDS crisis and are willfully ignorant of the disease. I also noticed that the individuals depicted were depicted with movement and was not sure if this was to represent dancing or another movement. I think that this can also be interpreted as “dancing” around the issue. I then read the plaque attached and it confirmed some of what I had described and interpreted from the piece. What I had not known was that Silence=Death was a key symbol in AIDS activism however Ignorance=Fear was something that Haring had added to bring more awareness to the need for education around the issue. Later when I was done with classes and took another look at my sketch I noticed more the straight line usage around their feet and head which makes it seem like they are in distress or agitated. I still do not know if there is a relevance to the other colors used in the piece.

Just as I had a calling to go back to the museum oftentimes art is a way to feel validated and represented. Museums and art, in general, are great creative expressions that can help heal individuals. Not only is art healing to the person who had created it, putting the emotion on paper or into clay but also to those who get to witness its beauty and messaging. Those who are struggling with mental health or a new possibly fatal diagnosis can walk the halls of a museum and find art that speaks to them in that moment. In many health crises often the individual can feel alone or isolated however finding an art piece that depicts what you are experiencing can validate you while also giving you inspiration on how to cope with your illness, through art. While a museum or creating art might not shrink a tumor or grow back a limb, it might just help someone through their journey and make them a healthier, happier person.

Synthesis Project:

Music Moves: Amplifying the Experiences of LGBT+ Youth Through Playlists of Resilience.

“Cause we are the hopeless, selfish, one of a kind, Millennium kids, that all wanna die”(Gray, 2018). Music has been a form of expression throughout every decade. Beats and melodies connect people by capturing both their joy and pain. Conan Gray is a young queer pop artist who shares his experiences and struggles through his music. This is a way that LGBT+ individuals can connect, find community, and feel validated in their experiences. LGBT+ youth have statistically higher rates of anxiety and depression and are 20% more likely than their peers to attempt suicide (Ream, 2022). While seeking mental health support has been widely advocated for among youth, efforts often fall short in addressing the specific needs of LGBT+ youth.

Specifically when looking at LGBT+ youth’s mental health, they have noticeably higher rates of suicide. A study conducted in Oregon by Hatzenbuehler found that LGBT+ youth had a 21.5% risk for suicide compared to their heterosexual peers had a 4.2% risk (Hatzenbuehler, 2011). This is a drastic uptick within the same geographical population that shows this increased risk. While this study focused on LGBT+ individuals as a collective within the community transgender and nonbinary individuals have an even greater risk of suicide. In 2020 a national survey in the United States partnered with the Trevor Project, found that, “Transgender and nonbinary youth were at increased risk of experiencing depressed mood, seriously considering suicide, and attempting suicide compared with cisgender lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, and questioning youth” (Price-Feeney et al., 2020).

While many often throw around these statistics there are often not many initiatives made to help those who have seriously considered or attempted suicide. However, in recent years initiatives and methods used for the greater spectrum of youth have been modified to apply to LGBT+ youth. In 2018 a music therapy tool was designed and tested for its benefits for the queer community. The study found that there were many strengths to the tool however, it needed additions to its design to better reach minorities and disparities within the LGBT+ community (Boggene & Grzanka, 2018). Through the implementation of Music Therapies LGBT+ youth who have attempted or seriously considered suicide can express their feelings and create a sensation of community and belonging.

My proposed intervention is to create group music therapy sessions for LGBT+ Youth who have seriously considered or attempted suicide by putting together playlists to depict their experiences and feelings. The group would be compiled of youth aged 12-18 who have attempted or considered suicide. These youth are reached through their school counselors, therapists, psychiatrists, and primary care physicians. The groups would range from 8-10 participants who identify as a member of the LGBT+ community. Groups would be organized to ensure that intersectional identities are present in each group. As this initiative would be formatted to be a study, parent or guardian approval is necessary for all participants under the age of 18.

Groups would meet weekly for an hour-long session, for 8 weeks. While longer sessions might be beneficial, keeping sessions consistent with typical therapy time commitments may allow for more participation. These sessions would be run by both a licensed music therapist, and a mental health expert (either a therapist or a psychiatrist). Eventually, previous group members could assist and provide testimonials for the group. If participants require accommodations or assistance in participating in the study paras, or caretakers are permitted to assist with study participation however, this must not be a parent. While parents may be the primary caretaker this could prohibit the youth from expressing themselves entirely. Similarly to therapy and psychiatrists if a participant shared that they are intending to cause themselves harm the parents would be notified.

Within the meetings, groups would check in and discuss both positive growth since the last meeting and setbacks. This will be a good opener to the group time however should not be longer than a third of the session’s time. Participants will then share songs that they have found, encountered, or written since the last session that speak to their experiences. While songs discussing mental health and suicide are expected, participants are encouraged to find songs that speak more to their queer identity, and how related struggles impact their mental health. In addition to these songs about their experiences, youth will also identify songs that bring them strength and help when they are struggling with their mental health.

The seventh session would have time dedicated to formulating a playlist composed of the songs that they found that spoke to their experiences. Participants would be allotted time in the following week to add or change their playlists. Before the last session, participants would also be asked to write a short statement of 100-150 words describing the themes they covered and expressed in the playlist. During the final session, students would share their statements and show their playlists. Students would be asked to play one song that well represented what their playlist was about. Following this session, youth are given the option to continue with the initiative and share the playlists that they have created.

The program would have three methods of spreading the information and playlists from the study to reach different audiences. One method would be to create a website that would house information about the groups, how to get involved, and educate on the risks. The site would also have a student music playlist tab which would anonymously house the participant’s playlists and statements. This site is to reach individuals who are experiencing serious thoughts of suicide, have attempted suicide, are friends with someone who has, and mental health professionals. Having a central place to organize both the project and the results will better engage the community than a paper. These audiences of younger generations are important to reach so that they can help a friend or themselves. However, to reach another important audience a second method can be used.

To reach an older audience that may not be actively looking for information surrounding LGBT+ issues may be more receptive to a radio or talk show hour. Sharing the playlists and their messages during rush hour periods. Throughout the hour the station would play songs selected from the playlists. The songs would be organized by their theming and the emotions they express. In between these music segments, radio hosts would discuss both the study and the purpose of educating LGBT+ issues and helping support LGBT+ youth.

Finally, for the parents of the participants, a group session would be held where the professionals share their children’s playlists and meanings. Professionals would share information anonymously, ensuring personal statements and playlists remain confidential. This way while they do not know what specific playlist is their own child’s they can apply what they learn from the overall collective themes to better understand and help their child.

Through both the focus groups themselves and the initiatives can address the gap in research and understanding when it comes to LGBT+ youth mental health. The groups will continue to help on a personal level with queer youth as they use music as a means of expressing and healing their well beings. Feedback from participants, music therapists, and mental health experts will guide improvements to the study’s effectiveness. In addition to this result through sharing the playlists and information surrounding the crisis of LGBT+ youth’s higher suicide rates the public can be more aware and educated surrounding these issues. Individuals who know LGBT+ youth who are struggling with suicide and self-harm are better equipped to understand their experiences and how to help them.

References

Boggen, Catherine & Grzanka, Patrick. (2018). “Perspectives on Queer Music Therapy: A Qualitative Analysis of Music Therapists’ Reactions to Radically Inclusive Practice.” Journal of Music Theory.

Conan Gray. “Generation Why.” Sunset Season, Republic Records, 2018.

Hatzenbuehler, Mark. (2011). “The Social Environment and Suicide Attempts in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youth.” Pediatrics.

Price-Feeney, Myeshia., Green, Amy., & Dorison, Samuel. (2020). “Understanding the Mental Health of Transgender and Nonbinary Youth.” Journal of Adolescent Health.

Ream, Geoffrey. (2022). “Trends in Deaths by Suicide 2014–2019 Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Questioning, and Other Gender/Sexual Minority (LGBTQ+) Youth.” Journal of Adolescent Health.