43 Farming Smarter: Strategies to Reduce Agricultural Runoff

Example Mitigation Strategies:

- Bioreactors:Bioreactors have emerged as a valuable tool in addressing nitrogen pollution from agricultural runoff. These systems treat drainage water before it reaches rivers and streams, using a trench filled with wood chips. The wood chips support bacteria that break down excess nitrogen, converting it into harmless nitrogen gas, which escapes into the air. This method is particularly effective in Iowa, where tile drainage systems—used to prevent flooding—can funnel nutrient-rich water directly into waterways, bypassing natural filtration processes like soil and wetlands (Practical Farmers of Iowa, 2022). (CK)One of the key advantages of bioreactors is that they integrate well into existing farming operations. Farmers can install them at the end of their tile drainage systems without needing to overhaul their practices. While maintenance is necessary (for example, replacing wood chips periodically), bioreactors can be an efficient, low-disruption solution for reducing nitrogen runoff (EPA, n.d.; Practical Farmers of Iowa, 2022). (CK)In terms of broader impact, bioreactors serve as a complement to other strategies like wetlands restoration and cover crops, both of which are well-established in runoff mitigation efforts. Excess nitrogen is a major driver of harmful algal blooms and dead zones in aquatic ecosystems, which can degrade water quality and harm human health. By capturing and converting nitrogen before it reaches waterways, bioreactors contribute to curbing the effects of nutrient pollution (EPA, n.d.; Iowa Department of Natural Resources, n.d.). (CK)In Iowa, where tile drainage is common, bioreactors help ensure that nutrient-rich water is treated before it enters rivers and streams. This is crucial for preventing the negative environmental impacts associated with nitrogen pollution. However, bioreactors should not be seen as a standalone solution. They are most effective when part of a comprehensive nutrient management plan that includes practices like buffer strips, nutrient management, and soil health improvements (Iowa Department of Natural Resources, n.d.; Practical Farmers of Iowa, 2022). (CK)Together, these combined efforts can significantly reduce nutrient runoff, protecting both water quality and public health. Bioreactors are an important part of a holistic approach to mitigating agricultural runoff, and when used alongside other strategies, they can help address the challenges posed by nitrogen pollution in Iowa (EPA, n.d.; Practical Farmers of Iowa, 2022). (CK)

2. Saturated Buffers:

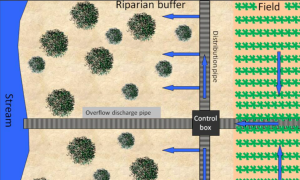

Saturated buffers are another effective mitigation strategy used to address agricultural runoff, particularly the nitrogen pollution that impacts water quality. This method involves installing a lateral tile system that runs parallel to a riparian buffer, diverting drainage water into the buffer zone before it reaches streams or rivers. A riparian buffer is a strip of land with plants—such as grasses, shrubs, and trees—that lies along the edge of a waterway. These plants act as a natural filter, catching and absorbing excess nutrients from the runoff before it enters the water. Once the water enters the buffer, it becomes saturated, allowing it to interact with both the soil and vegetation. In this zone, microbes and plants work together to remove excess nitrogen through denitrification and uptake. Saturated buffers are particularly effective in areas with flat terrain and well-established vegetation, where they can reduce nitrate levels by up to 85% (USDA ARS, 2022). Compared to bioreactors, which use wood chips to filter water, saturated buffers rely on natural plant and soil processes to achieve similar results. This strategy offers a low-maintenance, cost-effective solution for farmers, making it a promising tool in the effort to reduce nutrient runoff and protect water quality (Ohio State University, 2022). (CK)

Iowa’s Role in Agricultural Runoff

Iowa plays a huge part in the agricultural runoff issue, simply because of how much of the state is dedicated to farming. About 85–90% of Iowa’s land is used for agriculture, especially for growing corn and soybeans. These crops rely heavily on synthetic fertilizers, which contribute to nutrient runoff—particularly nitrogen and phosphorus—when rain washes the excess into nearby rivers and streams (EPA, n.d.). One major factor here is tile drainage. While this system helps farmers manage excess water and prevent flooding, the underground pipes also serve as direct highways for nutrient-loaded water to flow into rivers, bypassing natural filters like wetlands and topsoil entirely. (CK)

This has real consequences. A prime example is the 2015 Des Moines Water Works (DMWW) lawsuit, where the city’s water utility sued three upstream counties—Sac, Calhoun, and Buena Vista. The lawsuit claimed that tile drainage systems in those areas were sending high levels of nitrates into the Raccoon River, which DMWW relies on for drinking water. Nitrate levels were so high that the utility had to run its costly nitrate removal system for weeks just to meet safe drinking water standards. DMWW argued that these drainage systems should be considered point sources of pollution—meaning they discharge pollutants from a clear and identifiable origin, like a pipe—and therefore should require a permit under the Clean Water Act (Ohio State University, 2017). Traditionally, agriculture has been regulated under nonpoint source pollution, which refers to diffuse sources that are harder to trace and regulate, like runoff from entire fields. This lawsuit tried to challenge that framework by suggesting that tile systems act more like point sources, since they move pollutants in a direct and concentrated way. (CK)

Even though the lawsuit was ultimately dismissed in 2017—with the court deciding it was a matter for the legislature, not the courts—it was a wake-up call. It highlighted the gap between how pollution is defined legally and how it actually works in practice. And while DMWW chose not to appeal the decision, the lawsuit stirred a statewide and even national conversation about whether voluntary conservation is enough—or if more formal regulations are necessary to protect water quality (Des Moines Register, 2017). (CK)

This is where Iowa’s Nutrient Reduction Strategy enters the picture. The state’s plan aims to cut nitrogen and phosphorus loss by 45%, primarily through voluntary practices like cover crops, buffer strips, and wetland restoration. But since there are no strict requirements to participate, progress has been slow and uneven. Many environmental groups argue that while the strategy is a good start, it lacks the enforcement power needed to create large-scale change. As Iowa continues to wrestle with the balance between protecting agriculture and safeguarding public health, the legacy of the DMWW lawsuit remains a reminder that real accountability might require more than just good intentions. (CK)