12 Bioterrorism

Bioterrorism: What is it? Where has it been? Where is it going?

Disaster preparedness and response refers to the actions taken before, during, and after an emergency or catastrophic event (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) (Carr). This is an all-encompassing term to include disasters of many categories. The acronym “CBRNE” divides disasters into a variety of categories. Chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and high-yield explosives are the respective categories in this acronym. This section will discuss a type of biological threat that is a prominent issue in the modern world (CDC, “Bioterrorism Overview”). Bioterrorism is defined by the Center for Disease Control as “Intentionally releasing viruses, bacteria, or toxins to harm people, livestock, or crops” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)(Carr). This is a very broad definition to account for the many forms of bioterrorism that can exist. (MM)

Bioterrorism is a complex and highly volatile issue that has a history of creating mass casualty and mass chaos. Bioterrorism is used for many different personal and political agendas. There are many different ways that bioterrorism shows up in society and warfare. In this section, there will be exploration of prominent examples of bioterrorism, motives, results, and restorations being done in communities following bioterrorist events (CDC, “Bioterrorism Overview”). This section will explore the history of bioterrorism, levels of protections that are in place globally, nationally, and state-wide to prevent events of bioterrorism from occurring, and explore the future threats of bioterrorism (CDC, “Bioterrorism Overview”)(UNICRI)(Guillemin). (MM)

History of Bioterrorism

Bioterrorism has been a humanitarian threat for centuries. With origins as early as 1400 BC, events of bioterrorism are not novel (Carr)(Guillemin)(Biowarfare and Bioterrorism Timeline). Bioterrorism historically is motivated by civil or political unrest and is used as a mechanism for mass destruction, chaos, and trauma. Bioterrorism is not specific to one population, group of people, or political climate. There are thousands of examples of bioterrorism that have been enacted all around the world. From using contaminated clothing to attempt to harm and kill thousands of soldiers to infecting local restaurant food supplies to impact an election to infecting another species with the plague to cause mass destruction– there are so many different ways bioterrorism is seen on Earth (CDC, “Bioterrorism Overview”)(Biowarfare and Bioterrorism Timeline). In this section, there will be an exploration of prominent examples of bioterrorism over time and predictions for the future of bioterrorism as science, intelligence, and the world changes. Next are some notably alarming instances of bioterrorism in history to develop understanding of the broad scope of what bioterrorism can be (Biowarfare and Bioterrorism Timeline)(Carr)(Guillemin).

(MM)

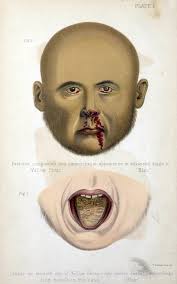

The United States Civil War: Dr. Luke Blackburn’s Attempted Yellow Fever Attack

Dr. Luke Blackburn was an experienced medical doctor known for providing humanitarian aid to nations impacted by infectious disease outbreaks like Yellow Fever (Carr)(Science History Institute, “Yellow Fever Fiend”). However, as civil unrest in the United States deepened and the nation grew closer and closer to civil war, Blackburn turned his knowledge into a weapon of mass destruction. His plan involved acquiring clothing and bedding infected with Yellow Fever and selling them to Union soldiers in hopes of spreading the deadly disease (CDC, “Bioterrorism Overview”)(Liese). (MM)

Despite his intentions, Blackburn’s plan ultimately failed because Yellow Fever is not transmitted through direct contact with contaminated clothing or bedding. Instead, it is a vector borne illness and is spread through mosquito bites, a crucial factor he overlooked. While this particular act of bioterrorism was unsuccessful, it highlighted the potential use of biological agents in warfare and raised concerns about the deliberate spread of infectious diseases as a means of warfare(CDC, “Bioterrorism Overview”)(Liese). (MM)

One of the most concerning parts about this attempt of bioterrorism is the realization that any person with knowledge of hazardous substances or diseases has the potential to cause a real disaster. Dr. Luke Blackburn had origins and humanitarian work. But, his hatred for the Union soldiers took over his motivation. Dr Luke Blackburn’s goals of helping people turned into the very opposite; an unimaginable twist of human evil (Carr)(Science History Institute, “Yellow Fever Fiend”). (MM)

Despite this public knowledge of Dr Blackburn’s attempts to kill thousands of people, Dr. Blackburn was still later elected as governor of Kentucky (Carr)(Science History Institute, “Yellow Fever Fiend”). This is a statement of the level of political unrest in the United States at this time as to where such an attempt at terror is overlooked. A leader was elected despite his horrifying background of attempting to kill hundreds of thousands of Union soldiers (Carr). (MM)

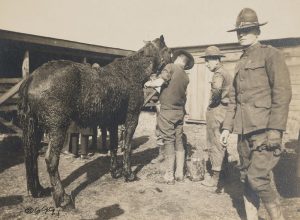

Tony’s Lab: Dr. Anton Dilger’s Anthrax and Glanders Bioweapons

Dr. Anton Dilger was an American-German doctor recruited by the German government to serve as a secret agent during World War I. With his advanced knowledge of microbiology, Dilger was tasked with creating biological weapons designed to inflict mass casualties on the American population and military assets (Wheelis)(Guillemin)(Koblentz). (MM)

Dilger established a secret laboratory where he successfully cultivated and weaponized anthrax and glanders, two deadly bacterial agents (Wheelis)(Guillemin)(Koblentz). These biological agents were then used to infect livestock and agricultural resources, leading to the deaths of over 3,000 animals and people. His bioterrorist activities posed a significant threat to food supplies, military resources, and public health. The case of Dr. Dilger demonstrates the potential for biological agents to be used as weapons in warfare, as well as the devastating consequences of such actions (Wheelis). (MM)

Similarly to that of Dr. Blackburn, this example of bioterrorism demonstrates the range of danger and threat that bioterrorism presents to humankind. Dr. Anton Dilger, a man of incredible intelligence of science and biological practices, uses his intelligence to cause extreme harm (Carr)(UNODA). Dr. Dilger worked with both the United States and the Germans but ultimately sided with the Germans. Causing extreme chaos and death, Dr. Dilger is yet another example of how the evil of humankind can utilize bioterrorism to reach their political and personal agendas (Wheelis)(Guillemin)(Koblentz)(Carr)(UNODA). (MM)

Japan’s Plague-Infested Fleas: The 150,000,000-Flea Infestation on China

During World War II, Japan engaged in a large-scale bioterrorist attack against China. A covert biological and chemical warfare research division. Japanese forces developed and released plague-infected fleas into Chinese cities, particularly in regions such as Ningbo and Changde (Koblentz), as part of a calculated effort to spread disease among civilians and enemy forces (Wheelis)(Guillemin)(Koblentz)(Carr)(UNODA).

The attack involved dropping approximately 150,000,000 fleas infected with a lab-grown strain of the bubonic plague from aircrafts over Chinese towns. The resulting outbreak led to widespread illness, suffering, and death (Harris)(Guillemin). The introduction of this laboratory-specific strain of the plague not only devastated the human population but also had long-term ecological effects by introducing a new invasive species to the environment. The use of biological warfare in this case stands as one of the most egregious examples of state-sponsored bioterrorism in modern history. There were mass casualties of civilians and irreparable damages to the Chinese people.

The bioterrorist attack made clear the possibilities of how harmful these attacks can be. Not only did this strain of the Bubonic plague that was crafted specifically for this event devastate the communities impacted, but the new and invasive species of flea led to eternal challenges with environmental change and disruption (Harris)(Guillemin). Yet again, this example of bioterrorism demonstrates the true level of harm that humans can cause (Harris) (Guillemin) (Koblentz) (Carr) (UNODA). (MM)

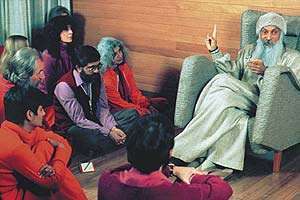

The Rajneeshee Bioterrorist Attack: Cult-Induced Salmonella Poisoning in Oregon

In 1984, a religious cult in Oregon, led by the controversial leader Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, orchestrated a bioterror attack with the aim of influencing a local election (Török et al.). The group hoped to make voters sick and unable to vote in order to manipulate the election outcome in order to ensure their preferred candidates would win positions of power in the local government (Koblentz)(Carr). (MM)

The cult members carefully planned their attack by cultivating Salmonella bacteria and contaminating salad bars at multiple restaurants in Oregon. Over the course of their systemic operation, they infected hundreds of residents. This led to widespread illness and disease in this community (Koblentz)(Carr). As a result, the voter turnout was significantly impacted, aligning with the cult’s objectives.In order to test this form of bioterrorist attack, the cult began assessing the efficacy of their infection methods through the salad bars, specifically the salad dressing stations in local restaurants (Koblentz)(Carr)(Török et al.). Following this, the members of the cult then infected the entire water supply for the city alongside their original plan of infecting salad bars and salad dressing stations. This led to over 700 cases of salmonella in the community and effectively incapacitated several voters from this community. Typically, there are around only five cases of salmonella in a community for a given year (Koblentz)(Carr)(Török et al.). (MM)

Beyond the immediate public health crisis, the attack raised serious concerns about the vulnerability of food sources and the potential for bioterrorism to be executed at a local level. It was one of the first documented instances of bioterrorism in the United States and demonstrated how individuals or politically driven organizations at the local level could weaponize biological agents to achieve their political or ideological goals. (MM)

This attack demonstrates the polarizing nature of politics and how bioterrorism is a real threat when political climates are unstable due to their effective nature in deterring or changing outcomes in official elections and proceedings. (MM)

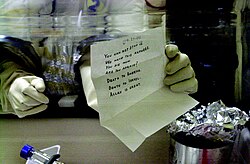

Amerithrax: The 2001 Anthrax Mail Attacks

The Amerithrax attacks of 2001 remain one of the most infamous cases of bioterrorism in modern U.S. history. Shortly after the September 11 attacks, letters containing anthrax spores were mailed to prominent news organizations and government officials, leading to the deaths of five people and infecting 17 others (Guillemin) (CDC, “Bioterrorism and Anthrax”). The attacks instilled widespread fear and uncertainty across the country, as authorities scrambled to determine the source and motivation behind them (Baumgaertner) (FEMA.gov) (Guillemin) (CDC, “Bioterrorism and Anthrax”). (MM)

Investigations led to the identification of Dr. Bruce Ivins, a scientist working at a U.S. government biodefense laboratory, as the primary suspect. Ivins was known for his expertise in anthrax research, and the strain used in the attacks was linked to his laboratory. Despite circumstantial evidence suggesting his involvement, Ivins died by suicide before he could be formally charged (Guillemin) (CDC, “Bioterrorism and Anthrax”).. This left a very dark and frightening tone in the United States. With extreme distrust of science and government workers and no clear answers, the Amerithrax attacks of 2001 leave a true stain of fear and devastation on the United States of America. (MM)

The Amerithrax attacks had profound consequences on national security policies and public health preparedness. In response, the U.S. government implemented stricter regulations on biological research and increased funding for biosecurity measures. The incident also highlighted the persistent threat of bioterrorism and the challenges associated with preventing and responding to such attacks (Baumgaertner) (FEMA.gov). Under the current administration, there are threats to cut or reduce monitoring and tracking of volatile substances and bioterrorism threats. As time goes on we move further and further away from the Amerithrax attacks of 2001, it is likely that there will be less and less understanding of the devastation that came from Amerithrax (Baumgaertner) (FEMA.gov). With this, there’s a threat of history repeating itself. Reducing regulations and monitoring is bound to cause more instability and less security for the United States (Guillemin) (Baumgaertner) (FEMA.gov) (CDC, “Bioterrorism and Anthrax”). (MM)

Global, National, and Local Protections Against Bioterrorism

To combat bioterrorism, governments and international organizations have established various layers of protection. Preventative systems in place vary greatly at the local level with customized differences based on the needs of different communities. For example, a community in Florida will have different protections and preventative measures in place than a community in the midwest. However, most communities have similar considerations for prevention of bioterrorism and terror related events. College campuses and universities and the surrounding communities are likely to have more protections in place for many reasons including a high prevalence of volatile materials in on-campus laboratories and learning facilities and a high density of people living in one area. With this in consideration, below is a generalized breakdown of the protections in place for each societal level. (MM)

Global Efforts

There are many interventions in place within the United States and beyond to work collaboratively with other nations of the world to prevent and prepare for bioterrorist events. There are prevention and protection efforts for disasters and crises of all kinds put in at the global level, but due to the volatile and unpredictable nature of bioterrorism, world leaders work together to deeply consider and work to prevent bioterror events. (MM)

The Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) prohibits the development, production, and stockpiling of biological weapons. This convention is one of the critical systems in place to prevent and control bioterrorism events in the international sphere. There was a treaty signed on April 10, 1972 and this agreement banned the use, production, and holding of biological weapons of mass destruction (United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs [UNODA]). (MM)

This treaty did not come into place out of nowhere. There were major historical events that were catalysts to stopping the production, development, and stockpiling of biological weapons of mass destruction. World War I was a notable time of bloodshed and chaos inflicted upon by the widespread use of bioterrorism and bioweapons. Japanese deployment of millions of lab developed fleas is one of the pivotal events that prompted regulations on the use of bioweapons. There were some regulations in place due to the Geneva Protocol to attempt to prevent bioterrorism events, but not enough. The Geneva Protocol is an international agreement that works to prevent the use of “asphyxiating, poisonous, or other gases, and bacteriological methods of warfare” (18 USC Ch. 10: BIOLOGICAL WEAPONS). This agreement, however, did not effectively stop and discourage the creation of new bioweapons and stockpiling of existing bioterror weapons. So, the biological weapons convention worked to fix this deficit in disaster preparedness and response and now provides complete and comprehensive prevention efforts of bioterrorist events. (MM)

Specifics of the BWC are illustrated in articles.

- Article I requires countries to not continue to develop or stockpile biowar agents for any reason at all. This article states that there is no justification at all to continue to develop these weapons (Koblentz 233).

- Article II required complete destruction of stockpiles that already exist including machinery used for deployment (Koblentz 233).

- Article III prohibits the sharing, donation, or transfer of biowarfare weapons to any party regardless of circumstances (Koblentz 233).

- Article IV is a call to action of peaceful use of biology and related science and collective international cooperation (Koblentz 233).

Overall, there are currently over 180 countries involved in this agreement but there are still some states that are non compliant or that have been found in violation (Wheelis, Rózsa, and Dando 22). Challenges with compliance are always going to be present in international agreements due to the broad call to action. There are not robust programs in place to ensure compliance and this makes it challenging to uphold the articles outlined in the BWC (Koblentz 235). In addition to this, there are extreme enhancements to research in scientific fields where there are more and more discoveries of dangerous biological advancements that need to be considered. Programs like BWC aim to maintain peace, but programs as such need to uphold the pace of the levels of technological advancement. (MM)

The UN Counter-Terrorism Center (UNCCT) is a global program that provides training for member states on terrorism events through capacity building, technical assistance and training courses. This program is one that stems from the work of the United Nations (UN). The UN Counter-Terrorism Center of UNCCT focused on providing technological support, support to build up safety precautions, and training services to members of the UN to better protect nations against the threats of terrorism and bioterrorism (United Nations Office of Counter-Terrorism). This program is in consideration of the laws of the international land and works to enforce things such as the BWC and uphold ideals from the Geneva Protocol. (MM)

The UNCCT was developed from the origins of the UN. This program was financially supported by nations in the UN with major contributions from Saudi Arabia. This program was developed to prevent extremism and behavior that is known to lead to terror and terrorism events. This program also aims to target broader goals such as promotion of equal human rights for all people in all places (United Nations General Assembly). This program is led and supported by UN agencies and has a board of advisors which includes nearly 2 dozen members of the UN that represent a diverse array of landscapes, leadership systems, and areas across the globe. This makes sure there is equal representation for the proceedings of the UNCCT adn all voices are heard in the decision making processes (UNCCT Annual Report 2023). (MM)

This program is broken down into pillars of action items and principles.

- Prevention of Violent Extremism- youth development programs, community resilience, and counter-narratives (UNCCT 2023).

- Border Security and Management- UN and the UNCCT supports states to create systems to uphold border security and detect terrorist travel (UNCCT).

- Protection of Vulnerable Targets- UNCCT works to protect places of worship, the public, and transportation networks (UNCCT 2023).

- Cyber Security and Counterterrorism in Technology Use- countering online radicalization, monitoring terrorist group propaganda, training local law enforcement on identifying terrorist propaganda (UNOCT).

- Prosecution, Rehabilitation and Reintegration- helping countries in teh UN to identirgy terrorists that have been prosecuted and help to reintegrate them with the guidelines of the human rights standards of the UN (UNCCT Annual Report 2023).

This program targets a wide variety of terrorist events and activities, but this is still a notable program that works in prevention of bioterrorism, biological attacks, and other categories in CBRNE.

The World Health Organization (WHO) monitors disease outbreaks and strengthens global preparedness for bioterrorist threats. WHO is a public health agency under the realm of the United Nations. This agency was established in 1948 and continues to lead the charge in public health prevention and emergency prevention in the biological sphere (World Health Organization, About WHO). (MM)

The headquarters of the WHO is in Switzerland with offices in over 250 countries. The overseeing body, aside from the UN, is the World Health Assembly or WHA. This brings together 194 members of the WHO and helps to involve all parties in decision making processes (World Health Organization, Governance). This body meets as a whole once per year to discuss budget and proposed plans for prevention on the international scale (Gostin and Meier 128). (MM)

The WHO has 6 core areas of focus in their program that work in prevention of public health disasters.

- Health Systems

- Noncommunicable Diseases

- Communicable Diseases

- Preparedness and Emergency Response

- Health Promotion and Environment

- Data Research and Innovation

(WHO, Thirteenth General Programme of Work).

There are many things within the WHO scope that work to address prevention of bioterrorism events. Among the most notable would be the prevention and intervention aspects of the WHO working to educate the public about potential risks. (MM)

National Protections (U.S.)

Among the extensive range of programs in the international scope are those in smaller scales. Countries across the world have individual programs in place to work to protect their communities. The United States has a variety of programs to prevent biological warfare and related disasters. The United States has had a complex history with bioterrorism and bioterror events which has encouraged the creation and development of these robust programs to prevent future disasters. As noted above, events like Amerithrax or Rajneeshee occured domestically and continue to inspire proactive preventative action. (MM)

Significant players in the role of prevention of bioterrorism events and disasters include, but are certainly not limited to, the CDC and Department of Homeland Security, and FEMA– the Federal Emergency Response Management Agency. (MM)

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) have biosecurity measures and response plans in place. The CDC works to Identify biological agents, monitor spread, and provide medical guidance for treatment and prevention. The CDC is mostly responsible for identifying and monitoring threats and spreads and distribution of guidance and advice for managing disease spread (CDC, 2022) (DHS, 2023). (MM)

Specifically related to biosecurity, the CDC has a Division of High-Consequence Pathogens and Pathology and an Office of Readiness and Response. These programs coordinate locally and nationally to manage disasters and plan responses for challenging pathogens. These offices work in collaboration with global partners to improve outcomes in emergency situations (CDC, 2022) (DHS, 2023). (MM)

The CDC works to stockpile necessary treatment supplies for highly volatile diseases and pathogens like anthrax, smallpox, and Ebola. CDC correlated agencies detect, contain, and diagnose national emergencies (CDC, 2022) (DHS, 2023). (MM)

The Federal Emergency Response Management Agency (FEMA) coordinates emergency response including logistics, resource allocation, and management of mass casualty events. FEMA is a sector of the US DHS and is in charge of the “response” part of disaster preparedness and response. There is less medical focus on response initiatives and more emphasis on the core logistical considerations of disaster response. Through training programs, response programs for different public entities, and distribution of protective materials, FEMA’s role is vast and critical (FEMA, 2019)(FEMA, 2020). (MM)

Local Readiness

Communities across the globe plan, prepare, and address bioterrorism threats and emergencies differently. For an example of a local action plan, below is a brief description and summary of the initiatives in place by the State of Iowa. (MM)

- Hospitals and emergency responders receive training for biological incident response.

- Cities have established disease surveillance and early detection programs.

- State of Iowa preparedness

- Iowa Health Disaster Council: IHDC. Public health information sharing venue that focuses on healthcare planning, preparedness initiatives, and response activities.

- Phase 1: Comprehensive needs assessment, medical direction, preparedness planning, initial implementation.

- Phase 2: Development and regional implementation of hospital and EMS services

- Iowa Health Disaster Council: IHDC. Public health information sharing venue that focuses on healthcare planning, preparedness initiatives, and response activities.

(University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics) (Upper Midwest Preparedness and Emergency Response Learning Center) (Iowa Department of Health and Human Services) (Polk County Health Department) (Iowa Disaster Human Resource Council) (MM)

Future Threats of Bioterrorism

With advancements in biotechnology and synthetic biology, new threats emerge. Gene editing tools could be misused to enhance pathogens, making future bioterrorism threats even more sophisticated. Governments must continue investing in surveillance, countermeasures, and research to stay ahead of potential biological threats. As mentioned above, changes in federal administration lead to changes in funding and different perspectives on the importance of preventative measures for Bio terrorism and public health. With reductions and funding, there is inherently more risk for a bioterrorism attack. There is less surveillance, less professional staff with the expertise to work to prevent and monitor bioterrorist threats, and less public health initiative work to educate the public on dangers of bioterrorism. (MM)

Understanding the history and impact of bioterrorism is crucial for global security and public health preparedness. (MM)

Public Health and Disaster Preparedness and Response in Washington D.C.

It is well known that as the transition to the new federal administration began in 2024 there was a significant shift in priorities toward improving the national debt status and reducing government spending. The administration took a particularly aggressive approach to identifying and cutting programs it viewed as unnecessary or excessive in alignment with goals and beliefs related to Trump’s Project 2025 (“Mandate for Leadership | a Product of the Heritage Foundation”). While fiscal responsibility and improvement is often a goal of leadership in the United States and beyond, this strategy has generated substantial public backlash on both sides of the aisle, particularly due to its immediate impact on federally funded research and grant programs (Baumgaertner) (FEMA’S ROLE IN MANAGING BIOTERRORIST ATTACKS AND THE IMPACT OF PUBLIC HEALTH CONCERNS ON BIOTERRORISM PREPAREDNESS). (MM)

Many of these programs, especially those dedicated to public health, education, and initiatives focused on minority populations, faced abrupt freezes in funding, new restrictions, or complete cuts. These constraints disrupted ongoing projects and limited the ability of organizations to investigate or respond to complex societal and health-related issues, including bioterrorism. This has led to a public health crisis. Specifically in the area of disaster preparedness and response in relation to CBRNE (FEMA.gov) (CDC Foundation). (MM)

These abrupt and unexpected changes have led to a notable increase in political engagement among public entities, academic institutions, advocacy groups, and private stakeholders (Mindy, Personal Notes). Many of these individuals and organizations depend on federal support for their survival or contribute to broader efforts for social and scientific advancement which has been made impossible or nearly impossible by the imposed cuts and restrictions of funding. (MM)

Among those taking part in this movement was Megan Mindy, the author of this chapter. In early April, Mindy traveled to Washington, D.C., through a University of Iowa–sponsored program aimed at educating legislators about pressing issues affecting communities and institutions related to the University of Iowa. The goal was to emphasize the consequences of current budget restriction choices and to advocate for the continuation of essential federal support for threatened or cut programs. (MM)

During her visit, Mindy attended the Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education Public Witness Day and the corresponding Subcommittee Hearing at the United States Capitol. The hearing was chaired by Representative Robert Aderholt, with Congresswoman Rosa DeLauro serving as the ranking member. The event provided a platform for ten witnesses from across the country to present the challenges facing their organizations in light of the current administration’s budget decisions (“Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education – Public Witness Day”) (Mindy, Personal Notes). (MM)

These individuals delivered deeply personal testimonies, each bringing stories from their respective communities. Their appeals ranged from calls for basic operational funding to in depth and passionate explanations of how cuts have threatened vital public services related to their community or organization (FEMA.gov)(Guillemin). One of the most impactful speakers was Christopher Frech, Co-Chair of the Alliance for Biosecurity. A former congressional staffer of eleven years, Frech returned to Capitol Hill to express his concerns about the federal government’s cuts to biodefense and public health preparedness (“Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education – Public Witness Day”). (MM)

Frech outlined the scope and significance of the work conducted by the Alliance for Biosecurity, which focuses on the development of vaccines, therapeutics, diagnostics, and medical devices. These innovations are designed in direct response to CBRN threats- chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear- including anthrax, smallpox, MPox, botulism, chemical weapons, and emerging dangers like fentanyl poisoning. Despite its private-sector status, the Alliance relies heavily on collaboration with the federal government. Its efforts serve as a leader of national disaster preparedness and emergency response. Bioterrorism was the main focus of Frech’s testimonial and the risks that have risen due to funding constraints (“Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education – Public Witness Day”). (MM)

During his testimony, Frech expressed grave concern over the depth of funding cuts facing programs critical to national security. He emphasized that the weakening of biosecurity infrastructure could place the entire country at risk. Among his key requests was a clear commitment to upholding the National Biodefense Strategy which is a framework that outlines how the country should prepare for and respond to biological threats. Without sustained investment (Frech) the nation’s ability to respond effectively to disasters could collapse. Not only could the preparedness initiatives collapse, but the safety, wellbeing, and prevention efforts of this organization would likely disappear. Bioterrorism threats are on the rise as the United States’ relationship with international entities rapidly changes and domestically, the extremely polarizing political climate is breeding civil unrest (“Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education – Public Witness Day”) (Mindy, Personal Notes). (MM)

Frech also raised concerns about the prior decision, under President Donald Trump, to withdraw the United States from the World Health Organization. He explained that if the U.S. intends to separate from international bodies that are responsible for prevention and public health monitoring, it must simultaneously enhance its domestic infrastructure through both public and private sectors. Frech once again touched on the powerful nature of working alongside federal administrations for preparedness, not separating power. Without this balance, the nation becomes vulnerable to global threats without sufficient internal resources to respond (Frech) (“Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education – Public Witness Day”). (MM)

Frech also emphasized the importance of preserving public-private partnerships, which allow for innovation and shared responsibility. These collaborations are essential to developing rapid responses to biological threats, but they cannot be sustained without consistent federal support. “Public-private partnerships depend on mutual trust and predictable funding. When funding becomes unstable, the partnership begins to erode, and the public faces the consequences (Frech- “Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education – Public Witness Day”)”. (MM)

The testimonies offered throughout the hearing made it clear that budget decisions impact people and organizations far and wide. Every dollar cut from public health preparedness or education weakens the infrastructure designed to protect the population. In areas such as biosecurity, underinvestment today could result in catastrophic outcomes on national and international fronts. As Frech noted, these concerns are not guesswork. They are grounded in the lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic and the gaps revealed in disaster preparedness and response during this time and decades of emergency response history (Frech- “Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education – Public Witness Day”). (MM)

Megan Mindy’s experience in Washington offered a front-row view of this urgent conversation on public health issues being under scrutiny in budgetary considerations. Her presence at the hearing was not only an educational opportunity but also a call to action. It revealed the crucial role that individuals, students, and professionals play in influencing policy. These efforts reflect a growing awareness that government policy, particularly concerning funding, must be informed by the realities on the ground and in the communities served (“Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education – Public Witness Day”). (MM)

As the current administration works to balance financial cuts with public responsibility, it must consider the long-term impacts of its decisions. Testimonies like Frech’s provide valuable insight into what is at stake. In many ways, these testimonies serve as evidence, not only of the need for funding but of the very real lives affected by decisions made behind closed doors and how these decisions can wreak havoc on centuries of preventative public health infrastructure that has been slowly developed and created in the United States (“Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education – Public Witness Day”). (MM)

Ultimately, Mindy’s participation in this program reinforces the importance of direct engagement in democratic proceedings. Advocacy at the federal level, especially when grounded in research, lived experience, and community representation, remains one of the most powerful tools for shaping a more equitable and prepared society (FEMA’S ROLE IN MANAGING BIOTERRORIST ATTACKS AND THE IMPACT OF PUBLIC HEALTH CONCERNS ON BIOTERRORISM PREPAREDNESS)(FEMA.gov)(CDC Foundation)(Mindy, Personal Notes)(Guillemin)(“Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education – Public Witness Day”)(Frech). (MM)

Reference List

- Carr, Joseph. Deadly Viruses and Warfare: A Historical Perspective. Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Bioterrorism Overview.” CDC, 2021, www.cdc.gov/bioterrorism/overview.html.

- Guillemin, Jeanne. Biological Weapons: From the Invention of State-Sponsored Programs to Contemporary Bioterrorism. Columbia University Press, 2005.

- Harris, Sheldon. Factories of Death: Japanese Biological Warfare, 1932-1945, and the American Cover-up. Routledge, 2002.

- Török, Thomas J., et al. “A Large Community Outbreak of Salmonellosis Caused by Intentional Contamination of Restaurant Salad Bars.” Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 278, no. 5, 1997, pp. 211-218.

- Wheelis, Mark. Deadly Cultures: Biological Weapons Since 1945. Harvard University Press, 2006.

- Promising Examples of FEMA’s Whole Community Approach to Emergency Management | CDC Foundation. (2025). Cdcfoundation.org

- https://www.cdcfoundation.org/whole-community-promising-examples CDC. (2024, June 21). Bioterrorism and Anthrax: The Threat. Anthrax.

- https://www.cdc.gov/anthrax/bioterrorism/index.html#:~:text=Bioterrorism%20involves%20intentionally%20releasing%20viruses,likely%20agent%20for%20such%20attacks.

- 4.7 Public Fear and Mental Health Impacts. (2023, May 30). Fema.gov. https://www.fema.gov/cbrn-tools/key-planning-factors-bio/kpf-4/7

- Biological Incident Annex August 2008 Biological Incident Annex BIO-1. (n.d.). https://www.fema.gov/pdf/emergency/nrf/nrf_BiologicalIncidentAnnex.pdf

- Preventing and Countering Bioterrorism in the wake of COVID-19 | Office of Counter-Terrorism. (2018). Un.org. https://www.un.org/counterterrorism/events/Preventing-and-Countering-Bioterrorism-in-the-wake-of-COVID-19

- Iowa Legislative Services Agency. (2021). Iowa Legislature. Iowa.gov. https://www.legis.iowa.gov/

- Joint Emergency Communications Center. (2025). Jecc-Ema.org. http://www.jecc-ema.org/ema/hazardmitigation.php

- Yellow Fever Fiend. (2023, May 15). Science History Institute. https://www.sciencehistory.org/stories/magazine/yellow-fever-fiend/

- FutureLearn. (2025). Biosecurity and Bioterrorism: Public Health Dimensions. FutureLearn. https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/biosecurity-terrorism

- UNICRI: United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute. (2020, July 2). Unicri.it. https://unicri.it/news/webinar-covid-19-and-future-pandemics-spectre-bioterrorism

- Biowarfare and Bioterrorism Timeline – 1960 through 2020. (2020). Auburn.edu. https://webhome.auburn.edu/~simmorb/samples/files/biotimeline/past/1960_2020.html

- The Ultimate Guide to Emergency Preparedness and Response. (2023, March 29). SafetyCulture. https://safetyculture.com/topics/emergency-preparedness-and-response/

- FEMA’S ROLE IN MANAGING BIOTERRORIST ATTACKS AND THE IMPACT OF PUBLIC HEALTH CONCERNS ON BIOTERRORISM PREPAREDNESS. (2025). Govinfo.gov. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-107shrg75441/html/CHRG-107shrg75441.htm

- Baumgaertner, E. (2017, May 28). Trump’s Proposed Budget Cuts Trouble Bioterrorism Experts. Nytimes.com; The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/28/us/politics/biosecurity-trump-budget-defense.html

- Mindy, Megan. Personal notes from the Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education Public Witness Day Hearing. United States Capitol, 4 Apr. 2025. Personal communication.

- Mindy, Megan. Personal summary of the Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education Public Witness Day Hearing. United States Capitol, 4 Apr. 2025. Heard live. Personal communication.

- “18 USC Ch. 10: BIOLOGICAL WEAPONS.” House.gov, 2024, uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title18/part1/chapter10&edition=prelim#:~:text=%E2%80%94Whoever%20knowingly%20possesses%20any%20biological,than%2010%20years%2C%20or%20both. Accessed 6 May 2025.

- GHS Index. Global Health Security Index 2021. Nuclear Threat Initiative and Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, 2021.

- Koblentz, Gregory D. “Biosecurity Reconsidered: Calibrating Biological Threats and Responses.” International Security, vol. 34, no. 4, 2010, pp. 96–132.

- Leitenberg, Milton. The Problem of Biological Weapons. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Oxford UP, 1997.

- Lentzos, Filippa. “Synthetic Biology and the BWC.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, vol. 67, no. 3, 2011, pp. 45–54.

- UNODA. “Biological Weapons Convention.” United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs, https://www.un.org/disarmament/biological-weapons/. Accessed 6 May 2025.

- Wheelis, Mark, Lajos Rózsa, and Malcolm Dando. Deadly Cultures: Biological Weapons Since 1945. Harvard UP, 2006.

- Liese, Andrea. “The Power of Human Rights in the Age of Counter-Terrorism.” Global Governance, vol. 25, no. 1, 2019, pp. 41–58.

- UNCCT. Annual Report 2023. United Nations Counter-Terrorism Centre, 2023.

- UNCCT and UN Women. Global Framework on Gender and Preventing Violent Extremism. United Nations, 2022.

- United Nations General Assembly. The United Nations Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy, A/RES/60/288, 2006.

- United Nations News. “UN Counter-Terrorism Chief Warns of Increased Threats from ISIL.” UN News, 22 June 2023, https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/06/1137682.

- United Nations Office of Counter-Terrorism. UNCCT Overview, https://www.un.org/counterterrorism/uncct. Accessed 6 May 2025.

- United Nations Security Council. Resolution 2396, S/RES/2396(2017), 21 Dec. 2017.

- UNOCT. UNCCT Cybersecurity Programme Highlights, United Nations Office of Counter-Terrorism, 2022.

- UNOCT. 2023 Strategic Review, United Nations Office of Counter-Terrorism, 2023.

- Burki, Talha. “The WHO’s COVID-19 Pandemic Response.” The Lancet Infectious Diseases, vol. 20, no. 5, 2020, pp. 529–30.

- Fenner, Frank, et al. Smallpox and Its Eradication. World Health Organization, 1988.

- Fidler, David P. “The Challenges of Global Health Governance.” Council on Foreign Relations Working Paper, 2010.

- Ghebreyesus, Tedros Adhanom. “Opening Address at the 148th Session of the WHO Executive Board.” World Health Organization, 2021.

- Gostin, Lawrence O., and Benjamin Mason Meier. Global Health Law and Governance: Concepts and Practice. Oxford UP, 2022.

- McCoy, David, et al. “The World Health Organization’s Funding Crisis.” The Lancet, vol. 372, no. 9642, 2008, pp. 2131–39.

- Piot, Peter, and Thomas C. Quinn. “Response to the AIDS Pandemic: A Global Health Model.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 378, no. 3, 2018, pp. 198–201.

- Usher, Ann Danaiya. “WHO Launches COVID-19 Technology Access Pool.” The Lancet, vol. 395, no. 10238, 2020, p. 2091.

- World Health Organization. About WHO. https://www.who.int/about. Accessed 6 May 2025.

- World Health Organization. Governance. https://www.who.int/about/governance. Accessed 6 May 2025.

- World Health Organization. International Health Regulations (2005). 3rd ed., 2016.

- World Health Organization. Strategic Priorities: Triple Billion Targets. https://www.who.int/about/what-we-do/triple-billion-targets. Accessed 6 May 2025.

- World Health Organization. Thirteenth General Programme of Work 2019–2023. https://www.who.int/about/what-we-do/thirteenth-general-programme-of-work-2019–2023. Accessed 6 May 2025.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Office of Readiness and Response: Emergency Preparedness and Response. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 28 Apr. 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/phpr/index.htm.

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security. BioWatch Program Overview. 10 July 2023, https://www.dhs.gov/biowatch-program.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency. Biological Incident Annex to the Response and Recovery Federal Interagency Operational Plans. U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Jan. 2019, https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_biological-incident-annex_01-2019.pdf.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency. Center for Domestic Preparedness Training Overview. 2020, https://cdp.dhs.gov.

- University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. Disaster Preparedness for Everyone. University of Iowa Health Care, https://uihc.org/disaster-preparedness-everyone. Accessed 6 May 2025.

- Upper Midwest Preparedness and Emergency Response Learning Center. About UMPERLC. University of Iowa College of Public Health, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Upper_Midwest_Preparedness_and_Emergency_Response_Learning_Center. Accessed 6 May 2025.

- Iowa Department of Health and Human Services. Emergency Preparedness & Response. Iowa HHS, https://hhs.iowa.gov/emergency-preparedness-response. Accessed 6 May 2025.

- Polk County Health Department. Emergency Preparedness. Polk County Iowa, https://www.polkcountyiowa.gov/health-department/services-and-programs/emergency-preparedness. Accessed 6 May 2025.

- Iowa Disaster Human Resource Council. Iowa’s Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster (VOAD). Safeguard Iowa Partnership, https://www.safeguardiowa.org/IDHRC. Accessed 6 May 2025.

- “Mandate for Leadership | a Product of the Heritage Foundation.” Mandateforleadership.org, 2023, www.mandateforleadership.org/. Accessed 7 May 2025.

- Ridge, Tom. “Tom Ridge and Joseph Lieberman: How Donald Trump Can Protect America from Bioterrorism.” TIME, Time, 13 Dec. 2016, time.com/4598145/donald-trump-biological-terrorism/. Accessed 7 May 2025.

- ChatGPT. “Discussion on Bioterrorism History and Protections.” OpenAI, 2025.

- Flaccus, Gillian. “Oregon Town Hasn’t Gotten over Its Bioterrorism Scare of 1984.” The Coos Bay World, 20 Oct. 2001, theworldlink.com/oregon-town-hasnt-gotten-over-its-bioterrorism-scare-of-1984/article_6f4b660f-b847-5512-859d-d83505a3e8b0.html. Accessed 7 May 2025.

- Watts, Jonathan. “Japan ‘Bombed City with Plague.’” The Guardian, The Guardian, 25 Jan. 2001, www.theguardian.com/world/2001/jan/25/jonathanwatts. Accessed 7 May 2025.

- “‘Tony’s Lab.’” National Archives, 18 Sept. 2017, www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2017/fall/tonys-lab. Accessed 7 May 2025.

- Newman, Tim. “Bioterrorism: Should We Be Worried?” Medicalnewstoday.com, Medical News Today, 28 Feb. 2018, www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/321030. Accessed 7 May 2025.

*AI tool used to assist in grammatical editing suggestions and research source gathering. Tool is cited above and all information is cited thoroughly with in-text style citations with exhaustive citation list.