32 Environmental Justice in Prisons

E.J. in Prisons

lchino

Introduction

Environmental justice touches just about everyone in society, directly or indirectly. It’s affecting the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the land we build on. Environmental Justice is the right that everyone is entitled to. The United States Environmental Protection Agency defines it as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income concerning the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies (US EPA, 2022). (LC)

Somehow, as society has progressed, the idea of environmental justice has been lost in application, particularly when addressing certain demographics and communities of people, such as those incarcerated. Incarcerated populations are consistently overlooked in environmental policies. From a country standpoint, this chapter will focus on how ecological justice affects those incarcerated in federal and state prisons across the United States. More specifically, it will focus on how prisons are often built in the worst conditions, making the living conditions exponentially worse and violating individual rights to environmental justice. (LC)

Background

For a background purpose, it is important to lay the groundwork of prisons, their initial goals, how locations are chosen, and the trends in those incarcerated. The birth of US prisons was in Philadelphia, dating back to 1790. Soon after, several other relatively small penitentiaries popped up in the Northeast. The main purpose of them is to keep “persons awaiting trial or execution hold runaways, slaves, indentured servants, and other law violators” (Musick & Gunsaulus-Musick, 2017). Mind, since this was so long ago, the caliber prisons were held to doesn’t come close to what it is now. Due to that, they were often built on the most unsought land in towns. This trend continued as those incarcerated were frequently viewed as outcasts in society. (LC)

However, the lack of knowledge about the impact of environmental elements was still unknown then. Now, the same line can’t be said. (LC)

As society has progressed, we’ve seen more intensive measures taken to address environmental justice inequities throughout the US, both at the state and federal levels. Yet, still, there hasn’t been much movement regarding the conversation of prisons and environmental justice. (LC)

How Location is Chosen

From the beginning stages, where a prison is located, environmental justice should come up. Often, there are conversions made of “former hospitals, mental health facilities, boys’ or girls’ training schools, industrial schools, college campuses, and forestry.” (Steinberg, Mills, & Romano, 2019). The conversion of old facilities into prisons that house the maximum capacity of persons poses environmental risks to those living and working in said facilities. From a high-level hazardous materials contamination perspective, there’s a higher risk of asbestos, lead paint, and polychlorinated biphenyls. These can be released during renovations, attempting to bring the structure up to code. These exposures most commonly can lead to respiratory issues, cognitive impairments, and reproductive health issues. Hand in hand, there is also a high concern about air quality and resource demand in these old buildings. (LC)

Prisons in America are also often built on or near hazardous land. As mentioned, this can be due to being converted from old structures. Most typically, these are built near or on landfills or chemical plants. (LC)

Billions of pounds of chemicals are released into the U.S. air, waterways, and land. Research and studies have shown a correlation to health consequences, from headaches to autoimmune diseases. While exposures are widespread nationwide, they are not equally distributed. (LC)

The U.S.’s Southern, Midwestern, and Mountain regions tend to have more toxic emissions than others (“Prison Ecology Project | Nation Inside,” n.d.). Areas with high poverty levels and large concentrations of people of color also tend to be more polluted (Evans & Kantrowitz, 2002). This opens the conversation to how, if every day, an individual is put at risk, how are those incarcerated affected by the toxic emissions? Of those detained in the U.S., which is roughly 1.2 million, 2/3 are identified as low income or have pre-existing health conditions. If those who are already in a vulnerable spot are then put into a prison that heightens all toxic exposure, who will the impact be? In a study done by Elisa L. Toman, she studied the correlation between prison location and emissions. Breaking down the density of the prison by ethnicity. (LC)

.

Physical Environments in Prison

Overcrowding

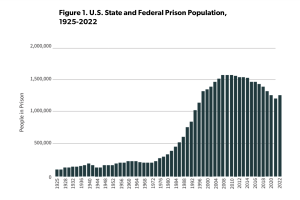

In the US, since the 1970s, there has been a massive influx in the incarceration rate, increasing by about 400%. This rate now puts us in first for the highest incarceration rate by country. In the 1970s, when President Nixon declared drug abuse to be “public enemy number one,” the “War on Drugs” began, initially causing an influx of incarcerated individuals. Since then, the US has ebbed and flowed with the number of individuals incarcerated, topping off at about 2 million today. (LC)

A graph from “The Sentencing Project” shows incarceration trends (Nellis, 2024)

While the number of people incarcerated has grown, the number of prisons has not been able to keep up at the same rate. This has been viewed as a social and political issue since the 1970s: “putting people in prison was easy, but building them was not” (Sawyer & Wagner, 2025). Originally, the answer was to fit as many people into one facility as possible, decreasing the quality of care as the ratio between prisoners and workers became skewed. However, as the rate of those incarcerated remained high, the boom in privatization of prisons happened. There was now a way to capitalize on those detained. This led to the flipping of abandoned facilities and less desirable land to be built upon, transforming them into prisons. Which, as previously discussed, also poses even more concerns with quality. (LC)

A necessary condition for the rapidly increasing incarcerated rate has been the “massive expansion in prison construction and capacity” (Sawyer & Wagner, 2025). As a result, cell blocks have become smaller while still typically remaining two to a block for standard prisons. Depending on the type and location of the prison, there may be a lack of green space or other open spaces for the inmates. (LC)

Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene

The overcrowding of prisons, combined with their lack of status in society, is a breeding ground for poor sanitation and hygiene. According to the World Health Organization, sanitation refers to the system and infrastructure used for managing all kinds of waste. At the same time, hygiene focuses on personal practices and behavior to prevent the spread of germs and diseases. Both of which are crucial to human health. As discussed in class, poor sanitation and hygiene can lead to the fall of countries, let alone stand-alone facilities like prisons. (LC)

Regardless of location in the U.S., the common thread regarding inmates and sanitation is rather poor in terms of appropriate language. Often, everything is communal or shared by at least two individuals. Many times, privacy is a privilege of the past. In a study done to look deeper into WASH inside U.S. prisons, a woman described her time as “’ feeling like I was not even a person, a woman. I felt as if I were just a caged animal to be observed, like in a zoo.’” (Crosson, Sylvester, & Worsham, 2024). She recalls this feeling being invoked by having a lack of sanitary products combined with a lack of privacy. The facility did not seem to have the resources to uphold the basic needs of those it was housing. (LC)

Another commonality was that the plumbing was often broken. This seemed to be a frequent experience, as the officers would dismiss it. At times, the problem would go days without being addressed. In extreme cases, correctional officers could interfere with the plumbing and deliberately withhold water (Crosson, Sylvester, & Worsham, 2024). (LC)

In prisons, everything is limited—a fixed number of resources are available to the inmates. This includes soap, toothpaste, and feminine hygiene products, which are the most basic hygiene products. Some facilities will include a wider variety, while the most crowded, public, and private facilities will not even have all the basics. The lack of products often dehumanizes the inmates, stripping them of dignity. (LC)

This systematic issue must be addressed at all levels, including the state and federal levels. The lack of knowledge of whether the water will work or the inability to access proper sanitary items violates human rights. In addition, not having privacy when using sanitation stalls adds another element to the mix. These things go beyond just hygiene and sanitation; they are also about preserving the human dignity of one of the most vulnerable populations. (LC)

Lighting and Noise

Lighting and noise are the last sections covered in the subsection on the physical environment in prisons. These are both factors that are put on the back burner when thinking about the overall production of a prison; however, they have proven to lead to worsening health conditions. Excessive lighting and noise exposure fall into the environmental justice category, as there is no way for one incarcerated person to control the amount of their exposure. (LC)

In prisons, the light source is almost always artificial, with minimal natural light exposure. Excessive number of lights affects not only sleep but tends to lead to long-term physical and mental health issues. Of those incarcerated, while it is not supposed to be a per se ‘comfortable’ way of life, it should cater to basic needs. Enforcing a different type of light rather than white light could contribute to better effects of sleeping and, therefore, improve sleep and wellness overall. (LC)

Excessive noise tends also to exacerbate preexisting health conditions, contributing to issues like hypertension and PTSD. In a study by Jacobson, following the line between loss of noise in prisoners, he concluded a ‘high incidence of hearing loss in the prison population’”(Moran, 2019). A lot of the time, these prisoners come into facilities with somewhat moderate hearing levels. Dependent on the amount of time spent in the facility determines the amount lost. The sources vary from fights between inmates to slamming cell doors and overhead speakers. Well, this is one of the more difficult problems to address. It’s worth noting that this is an environmental factor that inmates have no control over. (LC)

In prisons, these variables affect not only those incarcerated but also those staffed in the facility. This is a part of the problem when addressing environmental health issues within prisons because it is affecting incarcerated individuals who are being disproportionately marginalized. (LC)

Nutrition and Health Care Neglect

Access to Health Services

Healthcare is a fundamental right that those incarcerated are deprived of. The healthcare service is a broken system. This disparity is even more felt by those incarcerated. Prisons have the legal obligation to provide healthcare services to those incarcerated. However, the standard of care, like many other things in prisons, is extremely low. (LC)

For starters, the ratio between medical care providers and inmates is extremely skewed in all prisons, which impacts the quality of care doctors and nurses can physically give. Not to mention, the equipment they provide to perform care is limited. Public prisons turn to federal and state funding to ensure places like the infirmary are well-stocked. This is one of the first places it is felt when budget cuts are made. (LC)

Due to the nature of prisons, medical staff are always needed. There is no way around this problem. More medical staff will always be required to alleviate the pressure and workload for those already staffed. (LC)

Chronic conditions that are already present or worsen throughout one’s sentence may not receive proper care because of being short-staffed. Similarly, those injured throughout the sentence may not be given the best or adequate care depending on the injury or illness. This comes not only from being understaffed but also because of the goal of not having to outsource medical help. Having to send inmates to nearby hospitals to seek medical attention exhausts several resources, including guards, proper transportation, hospitals’ willingness to have the resources to house an inmate, etc. (LC)

Mental health counseling is another common health service that inmates do not receive adequate help with. Those in prisons are often at the lowest point of their lives, and not being able to have resources to help them work through mental health issues can result in the taking of life and harm to others or to oneself. Many prisoners enter with some prior history of mental health issues, addictive personality traits, or some physical condition, which again is almost always worsened when put into a confined space. The lack of ability to seek help with these problems only deepens the hole they are already in. (LC)

A barrier that seems to be prevalent in both the normal population and those incarcerated is the expenses that come with seeking medical attention. Even in prisons, there are some co-pays for medical visits. This poses a barrier and adds to a person’s willingness to seek help when needed. (LC)

Upon reading more about the healthcare disparities in prisons, it becomes apparent that the healthcare system is dysfunctional for all people in the U.S. and is felt more so with vulnerable populations. (LC)

The Takeaway

Environmental Justice is not just about having clean water and air, but also includes fair and accessible access to necessities. We are seeing a lack of that in prisons all around the United States. The incarcerated population remains one of the most vulnerable yet ignored populations. From prison location to lighting to everything in between, choices are made that further reveal systematic inequities. These conditions do not happen by accident but result from policies and laws being made. (LC)

The goal of prisons should be rehabilitation. Giving those incarcerated a fair chance with a clean, livable environment allows progress. If the environment is built to harm them and break them down, then the point of prisons has been lost. Addressing these injustices will require a policy change to happen not only at the federal level but also at the state level. If a blind eye keeps being turned when it comes to the prison population, there is just fuel being added to the fire. Environmental justice must extend to all people, including those behind bars. (LC)