11 Introduction to Disaster Preparedness and Response

smminer

What is Disaster Preparedness and Response?

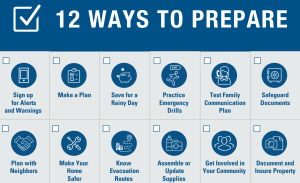

Disaster preparedness and response, also called emergency preparedness and response, is the practice of planning and preparation to ensure safety in the case of a disaster. The Primary objective of emergency preparedness and response is to protect lives by planning for potential disasters, swiftly responding to minimize damage when they happen, and limiting exposure to hazards and risks linked to an event. Preparedness happens before an incident occurs to help create a plan of action for when response is needed. It involves risk assessment and prevention strategies. (Paredes) Preparedness establishes a baseline for people to have the knowledge, skills, and supplies necessary in case a disaster occurs. Response occurs immediately after an incident and involves response personnel and mitigation of further hazards. (SM)

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) works to promote preparedness, coordination during a disaster, and recovery after a disaster on a national level. FEMA prepares the nation for possible risks through community understanding and engagement prior to the occurrence of a disaster. This is achieved through education and training as well as

community participation in everyday events. FEMA also offers a national Ready campaign which provides information on what tools and tips may be essential during specific emergencies or disasters. The campaign currently showcases information about winter weather, severe weather, wildfires, and power outages among many others. (How FEMA Works) (SM)

The history of FEMA outlines a nation dedicated to finding resilience amid disaster. The Congressional Act of 1803 followed a destructive fire in Portsmouth, New Hampshire in December 1802, and was the earliest legislative act regarding disaster relief in United States history. The devastation threatened the city’s commerce and Congress provided relief by suspending bond payments for several months following. On April 1, 1979, President Jimmy Carter signed Executive Order 12127, which established the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Just a few months later, on July 20, 1979, He signed Executive Order 12148 giving FEMA the dual responsibilities of emergency management and civil defense. In 1988, the Disaster Relief Act of 1974 was amended by the Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Amendments of 1988 and renamed the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act. The Stafford Act established clear direction for emergency management and established presidential disaster declarations that are still used in the current framework. On March 1, 2003, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security was created uniting FEMA and twenty-one other organizations. This followed the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and the signing of the Homeland Security Act in 2002 by President George W. Bush. After the devastation of Hurricane Katrina in August of 2005, Congress passed the Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act of 2006. Hurricane Sandy in 2012 devastated the East Coast and led to the Sandy Recovery Improvement Act of 2013. In 2017, a historic hurricane season in the Atlantic and wildfire disasters led to the enactment of the Disaster Recovery Reform Act of 2018. This legislation emphasizes the federal government’s commitment to investing in mitigation and building capabilities of partners at the state, local, tribal, and territorial level. (History of FEMA) (SM)

During a disaster, the local government will assess the damage to determine the impact and extent of incidence. When it is decided that local governments need assistance, a request for a federal disaster declaration is submitted. All declarations are made at the discretion of the President through the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act. The Stafford Act states that, “All requests for a declaration by the president that a major disaster exists shall be made by the Governor of the affected State.” A joint Federal, State/Tribal Preliminary Damage Assessment is conducted to determine the extent of the disaster, its impact on individuals and public facilities, and the types of federal assistance that may be needed. The results of the assessment are included in the request for a federal disaster declaration to show that the disaster is beyond the capabilities of the state and local governments. The Stafford Act describes two types of declarations, emergency declarations and major disaster declarations. Emergency declarations can be declared for any instance when it is determined that federal assistance is necessary. In this case, federal efforts are supplemented by providing emergency services to protect lives, property, public health and safety. For a single emergency, no more than five million dollars may be provided. If that amount is exceeded, the president must report to congress. Major disaster declarations are declared for any natural event that the President deems beyond the response capabilities of state and local governments. Major disaster declarations allocate more assistance than an emergency disaster declaration including federal assistance programs for individuals and public infrastructure. (How a Disaster Gets Declared) (SM)

Preparedness starts before a disaster begins. A basic disaster supplies kit ensures that an individual or household has the proper survival supplies in the case of an emergency. Food and water are among the most important items included in a disaster supplies kit, and each person should have enough of both to last several days. It is estimated that each person will need approximately one gallon of water each day for sanitation and hydration. Other items include flashlights, first aid kits, batteries, maps, and tools. In many emergency situations, the air can become contaminated with dust and debris from natural disasters, but chemical, biological, radiological, and explosive weapons pose risk to human health as well. A disaster supplies kit could also include dust masks to help filter contaminated air, plastic sheeting, duct tape, and scissors to shelter in place if necessary. (Build a Kit) (SM)

National Incident Management System

The National Incident Management System (NIMS) defines a common, interoperable approach regarding resource sharing, incident coordination and management, and communications in the case of national threats, hazards, and events. NIMS operates on principles of flexibility, standardization, and unity of effort. Components need to be adaptable to any situation as incidents vary widely. This scalability allows for a multifaceted approach involving multiagency, multijurisdictional, and multidisciplinary coordination. Incidents differ greatly in the type of hazard, geographical location and climate, demographics, culture, and organizational authority so it is essential for NIMS to maintain flexibility in their operations. Standardization ensures connectivity among multiple organizations during incident response measures. NIMS has standard definitions for organizational structures, practices, and terminology to maintain interoperability with effective communication. Unity of effort involves common objectives between various organizations through coordination. It allows support across multijurisdictional responsibilities while allowing them to maintain authority over their specific jurisdiction. Mutual aid is established through the NIMS principles. Due to the multijurisdictional approach across sectors, various public and private mutual aid systems can be utilized. Often, mutual aid agreements are established between neighboring communities as well as private sector organizations. (National Incident Management System: Third Edition) (SM)

National Response Framework

Four different categories constitute a public health emergency including the intentional or accidental release of a chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear agent, or explosives (CBRNE), natural epidemics or pandemics, natural disasters, and human-made disasters. The National Response Framework (NRF) provides structured response guidelines for all incidents that occur nationally. The NRF is used to implement NIMS and takes a community wide approach to coordination and response including government, private sector, and nongovernmental roles as a collaborative response. As identified in the NIMS principles, the NRF also functions off scalable, flexible, and adaptable concepts. The NRF provides a scope of information ranging from response to local incidents to those on a national level. The NRF defines the term “response” as action taken to save lives, protect property and environment, stabilize the incident, meet basic human needs following an incident, execution of emergency plans, and enabling of recovery. Goals and objectives are developed at local, state, tribal, territorial, insular area, and federal governments regardless of scale, scope, or complexity of the disaster. The objectives of the NRF aim at achieving the National Preparedness Goal, “A secure and resilient nation with the capabilities required to prevent, protect against, mitigate, response to, and recover from the threats and hazards that pose the greatest risk.” To reach this goal, five objectives of the NRF are taken from the Fourth Edition of the NRF as follows:

- Describe coordinating structures, as well as key roles and responsibilities for integrating capabilities across the whole community, to support the efforts of governments, the private sector, and NGOs in responding to actual and potential incidents.

- Describe how unity of effort among public and private sectors, as well as NGOs, supports the stabilization of community lifelines and prioritized restoration of infrastructure during an incident and enables recovery, including elements that support economic security, such as restoration of business operations and other commercial activities.

- Describe the steps needed to prepare for delivering the response core capabilities, including capabilities brought through businesses and infrastructure owners and operators in an incident.

- Foster integration and coordination of activities for response actions.

- and Provide guidance through doctrine and establish the foundation for continued improvement of the Response Federal Interagency Operational Plan (FIOP), its incident annexes, as well as department and agency plans that implement the FIOP. (National Response Framework: Fourth Edition) (SM)

In addition to the base document, the NRF includes Emergency Support Function (ESF) annexes and support annexes which provide details in assisting with the implementation of the NRF. The ESF annexes outline the federal coordinating structures that organize resources and capabilities into areas most frequently needed during a national response. The fifteen Emergency Support Functions are as follows:

- Transportation

- Communications

- Public Works and Engineering

- Firefighting

- Information and Planning

- Mass Care, Emergency Assistance, Temporary Housing, and Human Services

- Logistics

- Public Health and Medical Services

- Search and Rescue

- Oil and Hazardous Materials Response

- Agriculture and Natural Resources Annex

- Energy

- Public Safety and Security

- Cross-Sector Business and Infrastructure

- External Affairs (National Response Framework)

Support annexes detail other mechanisms where support is organized within private sector, non-governmental organizations, and federal partners. They outline essential support and considerations common to most incidents. NRF structures allow for a scalable response to each incident and can be partially or fully implemented at any time. Most incidents begin and end at a local level, so tiered levels of support are structured through the processes of the NRF. Support annexes include Financial Management, International Coordination, Public Affairs, Tribal Relations, Volunteer and Donations Management, and Worker Safety and Health. (National Response Framework) (SM)

Stabilization of community lifelines is a foundational component of the NRF. To protect public health and safety, the economy, and security, community lifelines become essential during response. There are seven community lifelines that represent the basic needs a community relies on. When the seven lifelines are restored and stable, all other activity is enabled. The community lifelines include Safety and Security; Food, Water, and Shelter; Health and Medical; Energy (Power and Fuel); Communications; Transportation; and Hazardous Materials. (National Response Framework: Fourth Edition) (SM)

Although the community lifelines do not directly include every important aspect of a community that can be affected by an incident, they encompass infrastructure, assets, and services. A community lifeline centered response allows for multijurisdictional alignment and prioritization of limited resources in both the public and private sectors. (National Response Framework: Fourth Edition) (SM)

CDC’s Priorities for Response Readiness (PRR)

The U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provides an agency-wide framework called Priorities for Response and Readiness (PRR) that aims to improve core capabilities regarding readiness and response capabilities across the CDC. The CDC is the nation’s health protection agency and a national security asset that focuses on preparation and response to public health emergencies and threats. The Priorities for Response and Readiness provide seven core capabilities for the CDC including planning, research, support, analysis, communication, mitigation, and detection. Efforts are put towards these seven core capabilities to improve readiness and response efforts. The Office of Readiness and Response works in collaboration with other experts from the agency to determine what actions can be taken over the next several years to improve each core capability. Input is gathered from lessons surrounding recent public health emergencies, the evolution of technology and science, and the anticipation of needs for the future. The PRR outlines two key goals, the first to identify the most significant readiness priorities for CDC attention and resources during the next three to five years, and the second is to assess the CDC’s progress accelerating response readiness. As a result, the PRR allows the agency-wide programs to accelerate readiness to respond as listed on their website by:

- Developing flexible and scalable resources

- Conducting applied research and evaluation to develop guidance and communication based in science

- Supporting jurisdictions’ readiness to respond through investments and guidance

- Expanding efforts to strategically place field staff

- Maintaining technical infrastructure and processes to support data sharing; Automate data collection and integration for real-time monitoring

- Strengthening risk communication activities to improve effectiveness in dissemination of critical public health information

- Expanding worldwide laboratory capacity to detect, diagnose, and monitor public health threats

- Prioritizing the development, clearance, and deployment of laboratory tests for public health threats. (CDC’s Priorities for Response Readiness) (SM)

Disaster Preparedness and Response Overview

Ultimately, there are many complex aspects of planning, preparation, and response to disasters. Nationally, we are given guidelines and management strategies that can be applied to various types of disasters on various levels. The United States has experienced many disasters throughout history, and we continue to see the need for public health and safety as well as disaster preparedness and response strategies. The following chapters will discuss Bioterrorism, Wildfires, Historical Disasters in the U.S., and Personal Reflections from the authors. (SM)

References:

“Build a Kit.” Build A Kit | Ready.Gov, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 9 July 2024, www.ready.gov/kit. Accessed 13 Mar. 2025.

“CDC’s Priorities for Response Readiness.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 7 Jan. 2025, www.cdc.gov/orr/about/cdcs-priorities-for-response-readiness.html. Accessed 05 May 2025.

“History of FEMA.” FEMA.Gov, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 4 Jan. 2021, www.fema.gov/about/history. Accessed 05 May 2025.

“How a Disaster Gets Declared.” FEMA.Gov, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 22 July 2024, www.fema.gov/disaster/how-declared. Accessed 05 May 2025.

“How FEMA Works.” FEMA.Gov, 23 Jan. 2024, www.fema.gov/about/how-fema-works. Accessed 13 Mar. 2025.

“National Response Framework.” FEMA.Gov, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 18 Apr. 2025, www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/national-preparedness/frameworks/response#esf. Accessed 05 May 2025.

“National Response Framework: Fourth Edition.” U.S. Department of Homeland Security FEMA, 28 Oct. 2019.

FEMA. “National Incident Management System: Third Edition.” U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 10 Oct. 2017.

Paredes, Rob. “The Ultimate Guide to Emergency Preparedness and Response.” SafetyCulture, 20 Dec. 2024, safetyculture.com/topics/emergency-preparedness-and-response/. Accessed 05 May 2025.