58 Water Regulations

ccschaefer

Introduction to Water Regulations

In order to guarantee safe and clean water supplies, governments and organizations around the world must regulate water. Water quality, pollution control, resource management, and access to safe drinking water are just a few of the topics covered by the wide range of laws and policies that make up water regulations. Governments can protect human health, maintain the environment, and guarantee sustainable development by enacting efficient laws at the local, national, and international levels (American Public University, 2023).

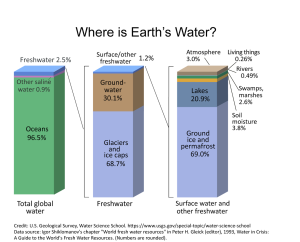

When looking at a satellite image, a map, or a globe, you can see how most of Earth is covered in water, 71% to be exact. Less than 3% of that is freshwater, which is needed to sustain life. Almost all freshwater is locked up in ice and in the ground. Only a little more than 1.2% of all freshwater is surface water, which serves most of life’s needs (Water Science School, 2019). Water is one of the most essential resources for life as it fuels ecosystems, supports agriculture, and is critical for human life. We take the quality of water for granted, despite it having a significant impact on public health and the environment. (CCS)

Figure 1: World freshwater sources

Figure 1: World freshwater sources

(Water Science School, 2019)

History of Water Regulations

Acting as a catalyst for environmental legislation, the 1969 Cuyahoga River Fire was an alarming wake up call in United States history. This fire in Cleveland, Ohio brought national attention to the state of our nation’s waterways.

On June 22 1969, a spark from a passing train or a nearby piece of equipment ignited oil and industrial waste floating on the surface of the Cuyahoga River. The fire, though quickly extinguished, burned intensely enough to cause damage to railroad bridges that crossed the river. While short lived and not the first of its kind, it later caught national media coverage from the New York Times and National Geographic, starting an uproar. The attitude amongst American’s began to change; environmental integrity would take reign over the booming industrial manufacturing pollution (Boissoneault, 2019).

At the time, the Cuyahoga River was so polluted it was often described as a “flowing dump for industrial waste.” Industries such as steel manufacturing and oil refineries along the river routinely discharged untreated waste into the waterway. For many years, this pollution was worn as a badge of honor as pollution meant industry was booming, jobs were created, and the economy was thriving (Boissoneault, 2019). But, the particular fire this day struck a nerve in the American people due to growing environmental awareness during the 1960s. When Time magazine ran the story on the fire , it noted the river “oozes rather than flows” and that a person “does not drown but decays” if they fall in the river (Time, 1969).

The national outrage this fire provoked helped fuel an environmental movement in the United States. The fire helped influence the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970 and the passage of significant federal legislation like the Clean Water Act of 1972. These actions are meant to regulate and reduce water pollution, prevent similar environmental disasters, and restore the health of American waterways.

Today, the Cuyahoga River remains a monumental moment in U.S. environmental history. It was a fiery wake up call that demonstrated the urgent need for environmental stewardship and regulation. (CCS)

Figure 2: Firemen stand on a bridge over the Cuyahoga River to put out fire.

Figure 2: Firemen stand on a bridge over the Cuyahoga River to put out fire.

(Boissoneault, 2019)

The Environmental Protection Agency

With the goal of safeguarding both the environment and human health, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the U.S. carries out the environmental laws passed by Congress by creating regulations. In order to lower pollution and advance sustainability, the EPA manages programs, conducts research, and offers education. The EPA is essential for protecting natural resources for current and future generations through public awareness campaigns and regulatory enforcement (EPA, 2024).

The Clean Water Act is one of EPA’s major initiatives. This important law, which was passed in 1972, was designed to control water contamination and protect American water supplies. This Act establishes quality criteria for surface waters and the fundamental framework for controlling pollution discharges into waterways. Additionally, the Clean Water Act gives the EPA the power to enforce laws for businesses and towns and to carry out pollution control (EPA, 2024).

Another initiative is the Safe Water Act, which regulates the nation’s drinking water supply, which includes groundwater wells, lakes, reservoirs, springs, and rivers. Private wells that serve less than 25 people are exempt from EPA regulations. The EPA establishes health-based regulations, similar to the Clean Water Act, to shield the public from pollutants. Without this legislation, human hazards, subterranean waste injections, pesticides, animal waste, poorly disposed of chemicals, and naturally occurring contaminants would all constitute a threat to our drinking water in the United States. There are health concerns associated with drinking water that has not been adequately cleaned, treated, or distributed through a system. (Office of Water , 2004).

As we dive deeper into environmental regulations, specifically water regulations, we will take a closer look into how these regulations are doing at maintaining water quality at the state, national, and global levels. (CCS)

Water Quality

Water quality refers to the chemical, physical, and biological characteristics of water (Water Science School , 2018). Water quality determines its suitability for drinking, recreation, and industry. Water pollution occurs when harmful substances such as heavy metals, bacteria, pesticides, and plastics enter bodies of water. This pollution makes the water unsafe to consume and can lead to adverse health effects. Ensuring access to clean and safe water is a global health priority. Contamination from pollutants, industrial waste, and agricultural runoff threatens both human health and the environment (Denchak, 2023).

Water quality is a critical issue in Iowa, influencing public health, environmental sustainability, and the state’s agricultural economy. Despite ongoing efforts to monitor and improve water conditions, challenges persist due to factors such as agricultural runoff, industrial activities, and aging infrastructure.

Iowa’s water bodies face significant impairment. According to the Iowa Department of Natural Resources (DNR), there are at least 721 water body segments in the state that do not meet water quality standards for recreation, public water supplies, and the protection of aquatic life. (Strong, 2024) This means that over half of the tested streams and lakes are classified as “impaired,” indicating widespread pollution concerns that require immediate attention. A list of impaired waters is sent to the EPA every two years to guide restrictions on pollution.

While we have declined four percent from the last report in 2022, just 24% of stream segments and 30% of lakes were considered “healthy” (Strong, 2024).

The degradation of water quality affects not only aquatic ecosystems but communities that also rely on these water sources for drinking and agricultural use. If over half of our waterway segments–which can be lakes, wetlands, and parts of streams, are deemed unhealthy, the conversation surrounding water quality in Iowa should be of major concern.

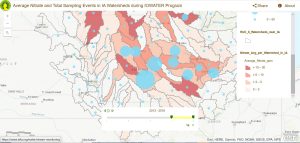

One of the most pressing issues affecting Iowa’s water quality is nutrient pollution, primarily from nitrogen. Nitrate occurs naturally in low concentrations, but excessive nitrate in water can cause environmental and human health risks. Nitrogen is typically the most abundant nutrient in chemical fertilizers used on farm fields, lawns, golf courses, and gardens, and this nitrogen becomes nitrate as it moves through the environment. Sewage, faulty septic systems, and animal feedlots can also be big contributors of nitrate. The map below shows nitrate levels in Iowa watersheds measured by the IOWATER program. (Izaak Walton League of America, n.d.)

Figure 3: Average Nitrate and Total Sampling Events in IA Watersheds during IOWATER Program

(Izaak Walton League of America, n.d.)

IOWATER, a statewide volunteer water monitoring program, played a significant role in assessing water quality across Iowa for nearly two decades. While no longer active, the magnitude of its community-driven data collection illustrates the importance of public engagement in environmental monitoring (Izaak Walton League of America, n.d.) .

The water quality in Iowa makes a major impact nationally. With the Mississippi River as our east border, excess nutrients from out state reach the Gulf. This excess nutrients stimulates an overgrowth of algae, which eventually die and decompose, depleting oxygen as they sink to the ocean floor. With the low oxygen levels near the bottom of the Gulf, marine life cannot be supported. Fish, crabs, and shrimp often move out of the area, but this is not always possible. The stress and inability to move out of low oxygen levels leaves a large dead zone, that occurs almost every summer. In 2020, the Gulf of Mexico Dead Zone measured 2,116 square miles, which is larger than the state of Delaware. (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), 2020)

According to the USGS, more than 50% of the sources delivering nitrogen to the Gulf is from corn and soybean crops, with Iowa ranking number one in the nation for production of these crops. In 2022, almost 30,000,000 acres of land were used for farming in Iowa (USDA, National Agriculture Statistics Service, 2022).

Efforts to improve Iowa’s water quality require a multifaceted approach that includes policy interventions, conservation strategies, and community engagement. One of the key initiatives in place is the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy, which aims to reduce nutrient loss. Created in 2013, the goal of this strategy is a total reduction of Nitrogen and Phosphorus by 45%, particularly from non-point sources. This involves implementing conservation practices, such as cover crops and buffer strips, to minimize runoff and improve soil retention (Clean Water Iowa). Additionally, promoting soil health through practices like no-till farming and the use of prairie strips has proven effective in reducing soil erosion, combatting nutrient pollution, and supporting biodiversity. Research has shown that prairie strips can reduce soil erosion by up to 95%, making them an essential tool in improving water quality in Iowa and beyond (The Guardian, 2024). Since a majority of excess nitrate comes from non-point sources, these practices cannot be mandated, just encouraged. Farmers voluntarily adopt better practices. As a public health student, I am interested in understanding the knowledge gap of landowners and farmers in their contributions to excess nutrients contributing to water quality issues in Iowa. We must make landowners and farmers aware of the Gulf Dead Zone and the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy in order to reduce water quality issues in not only Iowa, but the nation. (CCS)

Violating Water Regulations in Iowa

In Iowa, the DNR regulates our water. The Iowa DNR differs in enforcement of EPA regulations as the instrument of choice is voluntary compliance with national standards. The DNR continually encourages better actions. “Enforcement must take place when people choose to circumvent the law or do not understand the full impact of their actions on our environment. The compliance portion of the DNR improves our environment through educating citizens and promoting awareness.” (Iowa DNR, n.d.) Unlike national standards, in Iowa a consent order is issued alternatively to issuing an administrative order. With a consent order, the DNR voluntarily enters a legally enforceable agreement with the other party (Iowa DNR, n.d.).

My first example of water regulations being violated is with Brian Behrens in Carroll County, Iowa. Behrens violated animal feedlot operation regulations and water quality regulations that were discharged from his facility. “The administrative consent order (Order) requires Mr. Behrens to pay an administrative penalty of $2,500.00 pursuant to a payment plan, to implement a plan of action to prevent all discharges from the Feedlot, to maintain a heard of less than 300 head of cattle at the Feedlot until the plan of action is implemented, and in future comply with the laws and rules governing the animal feeding operations and water quality for the waters of the state.” (Iowa Department of Natural Resources Administrative Consent Order, 2020). This case highlights the importance of enforcing environmental regulations to protect Iowa’s water quality and ensure responsible management of animal feeding operations.

This next violation is with Calcium Products, Inc. in Webster County, Iowa. In 2020, Calcium Products Inc., a Fort Dodge-based fertilizer manufacturer, was fined $6,700 by the Iowa DNR for illegally and “unknowingly” discharging lignin sulfonate, a chemical used in its production process, into a creek that feeds the Des Moines River. The company attributed the incident to faulty equipment. As part of a consent order, the company agreed to the fine and committed to preventing future discharges (Decious, 2020).

In some cases, a company will notify the Iowa DNR about a spill they had at their facility. This past April, the DNR began investigating a fish kill in the South Branch of Lizard Creek in Fort Dodge after a fertilizer byproduct from CJ Bio America leaked into a stormwater channel and ultimately reached the creek. Although plant staff initially believed the spill was contained, but there was an issue with the berm (a flat strip of land, raised bank, or terrace bordering a river or canal), allowing an unknown amount of the byproduct to enter nearby surface water. DNR officials found the substance and dead fish several miles downstream (Koons, 2025).

The cases I’ve highlighted above demonstrate a range of water regulation violations in Iowa, from improper management to chemical discharges. While the Iowa DNR often promotes voluntary compliance and education to encourage adherence to environmental laws, enforceable actions like consent orders and fines are essential tools when violations occur to maintain environmental stewardship. Whether these violations are through accidental releases or failure to follow established guidelines, these incidents should make our public health officials, legislatures, and companies more proactive in prevention. Moreover, if you see something, say something. It is important to have timely reporting to reduce health risks and environmental damage. Lastly, our major polluters must be held accountable in order to keep Iowa’s waterways protected and the communities and ecosystems that rely on them safe. (CCS)

Regulating Water Nationally

As stated earlier, the EPA is federal agency that in part aims to protect water quality and ensure safe drinking water for people and the environment. The EPA sets national standards, while implementation and enforcement are often delegated to state environmental agencies, which may interpret and apply federal rules differently.

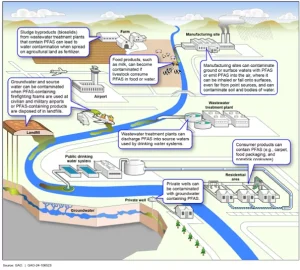

70,000 water bodies nationwide do not meet water quality standards. It is likely that across the country, most people have been exposed to per- and polyfluoralkyl substances (PFAS). PFAS are forever chemicals that can persist in our water, food, and air and cause adverse health effects (U.S. Government Accountability Office, n.d.).

Figure 4: Examples of How PFAS Enter the Environment

Figure 4: Examples of How PFAS Enter the Environment

(U.S. Government Accountability Office, n.d.).

The EPA’s major concerns that pertain to the quality and safety of waterways in the United States includes but is not limited to:

- Contaminants

- Cybersecurity

- Infrastructure funding

- Lead in drinking water

- Nonpoint source pollution

- Climate change

- Watershed restoration

- Sewage overflow

- Toxic algae

- International boundaries

To focus on one of these concerns, I will be discussing how lead in our drinking water remains a significant public health concern.Lead pipes were once claimed to be the most durable infrastructure solutions but are now recognized as a “silent killer” in America. Even in small amounts, lead exposure can cause neurotoxic damage, developmental delays in children, and an increased risk of chronic diseases. Even with these adverse health effects, the threat has remained overlooked.

According to an article published in the Daily Galaxy, “The EPA’s Lead and Copper Rule Improvements (LCRI), introduced in October, aim to tackle this long-standing issue. Over the next 10 years, utilities are required to identify and replace all lead service lines. These stricter measures also include rigorous water testing and improved community communication to ensure families are informed about risks, the locations of lead pipes, and plans for replacement.” (Amiri, 2024)

In urban centers like Iowa City, water contamination takes a different form. Aging infrastructure, particularly lead service lines, presents a serious health risk. In response, the city has implemented the Lead Reduction Program and developed a Lead Service Inventory to identify and replace hazardous pipes (Iowa City Government, 2023). These efforts align with national initiatives to eliminate lead exposure through drinking water, especially in vulnerable populations. (CCS)

Violations

Water violations can escalate to federal crimes under environmental laws when there is evidence of criminal intent or negligence. The EPA’s criminal enforcement policies allow for prosecution in cases involving illegal pollutant discharges into protected waters, failure to report such discharges, or tampering with public water systems.

In 2021, the owner and president of Oil Chem Inc. was sentenced to 12 years in prison for violating the Clean Water Act. Robert J. Massey was illegally discharging industrial waste over the span of eight years. The facility totaled more than 47 million gallons into Flint, Michigan’s sewer system. Oil Chem Inc. had a permit that prohibited them from discharging landfill leachate waste. “Landfill leachate is formed when water filters downward through a landfill, picking up dissolved materials from decomposing trash.” (U.S. Department of Justice , 2021). Massey told employees at the facility to discharge the leachate at the end of business hours so waste would flow out during the night, showcasing criminal intent.

This case is notable because of the location. Flint, Michigan was already facing the public health crisis of lead contaminated drinking water. Massey’s actions further endangered the Flint community already suffering from unsafe water.

Another federal case of water violations occurred in December 2021. Louie Sanft, the owner of Seattle Barrel and Cooperage Company, was sentenced to 18 months in prison after being convicted of conspiracy, 29 Clean Water Act violations, and making false claims to federal investigators. For more than a decade, Sanft directed his employees to illegally discharge the cleaning materials for industrial barrels into the King County sewer system. This waste bypassed the required treatment processes and entered the sewer system through a hidden drain that was purposefully installed to conceal the discharges from authorities. After years of county monitoring and data collection, the EPA obtained a search warrant a discovered the hidden pump leading directly into the sewer. In addition to the environmental violations, Sanft created false compliance certifications and misled investigators about his company’s practices. I highlight this case because it is a clear breach of environmental law and demonstrates the dangers of intentional pollution to make financial gains.

Water quality is not just a pressing public health challenge for Iowans. From PFAS contamination to lead exposure and criminal violations of the Clean Water Act, it is a health concern for individuals and ecosystems across the country. As a nation, we must continue to invest in our infrastructure, remain transparent, and hold companies and individuals accountable to continue our valuable water resources for generations to come. (CCS)

Regulating Water Globally

Regulating water on a global level varies depending on a country’s government, infrastructure, and economic resources. Water quality efforts are often led by organizations such as the United Nations, the World Health Organization (WHO), and the World Bank. Together, these entities set up international water standards, fund infrastructure development, and promote equity. Enforcement of water policies can be inconsistent across the globe. Lower income countries may may face challenges in poor sanitation infrastructure, lack of monitoring abilities, political instability, and industrial pollution. Moreover, climate change and population growth put pressure on global water systems.

One of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is Clean Water and Sanitation, as well as Life Below Water. The SDGs are a “…a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future. … are an urgent call for action by all countries – developed and developing – in a global partnership. … strategies that improve health and education, reduce inequality, and spur economic growth – all while tackling climate change and working to preserve our oceans and forests.”

The sixth goal ensures availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. In 2022, 2.2 billion people lacked safely managed drinking water. 3.5 billion people lacked safely managed sanitation. 2.2 billion people lacked basic handwashing facilities (United Nations, 2024). Goal six has total of eight targets, 37 publications, 301 events, and 1850 actions. The other goal that relates to water, goal 14, is to conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development. This SDG aims to combat coastal eutrophication, ocean acidification, ocean warming, plastic pollution, and over-fishing (United Nations, 2024).

While the SDGs are not legally binding, efforts like The Water Convention support the implementation and monitoring efforts to reach SDGs. Originally adopted in 1992 under the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), the convention was opened to all United Nations members in 2016. The primary aim of The Water Convention is to promote cooperation between countries that share rivers, lakes, and groundwater resources, to prevent conflict, protect ecosystems, and sustain water management. The Water Convention also sets legal and institutional frameworks for joint monitoring, information sharing, early warning systems, and dispute resolution. Over 150 countries share transboundary waters, and this agreement plays a vital role in encouraging peaceful collaboration over shared water sources, to avoid conflict in regions where water scarcity can intensify political tensions. António Guterres, United Nations Secretary-General states, “The Water Convention can help the world respond to the global challenge of sharing transboundary water resources in a sustainable and peaceful manner. I urge all United Nations Member States to accede to and implement this indispensable tool.” (UNECE, n.d.)

Effective global water regulation requires strong partnerships, sufficient resources, and political will. While international frameworks like the SDGs and the Water Convention offer guidance and support, their success depends on national commitment and local implementation. Coordinated international efforts remain crucial to ensuring safe, sustainable, and equitable access to water for all. (CCS)

Challenges to Regulating Water

Fragmented Oversight: Water regulation is split among multiple agencies like the EPA, state departments, and local utilities, leading to inconsistencies (GAO, 2018).

Aging Infrastructure: The U.S. faces an estimated $744 billion need for water system upgrades over the next 20 years (EPA, 2021).

Emerging Contaminants: Substances like PFAS are widespread but not yet fully regulated under the Safe Drinking Water Act (EPA, 2024; NRDC, 2022).

Funding Gaps: Many small and rural systems lack resources to meet regulatory standards (Congressional Research Service, 2023).

Climate Change: More intense droughts, floods, and changing precipitation patterns complicate regulation and water quality (IPCC, 2022; NOAA, 2023).

Equity and Access: Marginalized communities are more likely to face water quality violations and affordability issues (UCS, 2021; EWG, 2022).

(CCS)

What We Can Do

Actions must be taken at each level when following regulations including individuals, businesses, and governments. Here is how we can follow and support water regulations:

Individual Action

- Learn about your local water quality reports and regulations which are available through utilities or the EPA. By staying informed, you can ….

- Properly dispose your waste. Avoid flushing medications and chemicals down drains.

- If you notice illegal dumping or contamination, report it to the Iowa DNR, local authorities, or the EPA.

Business and Community Involvement

- Industries and fames must comply with discharge limits under relevant environmental laws (i.e. Clean Water Act).

- Adopt environmentally responsible practices such as buffer zones near bodies of waters or upgrade wastewater treatments.

- Engage with the public by supporting community efforts like IOWATER water quality monitoring efforts.

Government and Policy Level

- Ensure local, state, and federal agencies have the resources to inspect, monitor, and enforce regulations and standards.

- Support investment in infrastructure upgrades

- Advocate for stronger and update water laws to address current concerns like excess nutrients, PFAS, and climate change impacts.

(CCS)

Conclusion

Water regulation remains a critical and complex aspect of public health and environmental protection. As outlined in this chapter, efforts to ensure safe and sustainable water span multiple levels from local actions in Iowa to national standards enforced by the EPA, and international cooperation through frameworks like the Sustainable Development Goals and The Water Convention. While making progress, water resources still face challenges with climate change and emerging contaminants. However, meaningful change is still possible. Through individual action, big business engagement, and string governmental leadership, we can work toward a future where clean water is guaranteed for all. Now understanding the systems in place and the gaps that remain, we can all advocate for policies and practices that protect our most essential resource for life. (CCS)