22 Chemical Policy and Regulation (JP)

Chemical policy and regulation

Introduction to Chemical Hazards and Regulatory Frameworks

Before examining the labor laws and legislations that safeguard workers and encourage to apply safety measures in chemical-processing industries, it is essential first to clarify the definition of chemical hazards and how they affect the human body and the environment. Based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), chemical hazards are substances—ranging from solutions, vapors, gases, and aerosols to other particulate matter—that may be toxic or irritating to the human body[1]. These chemicals can also have detrimental effects on the environment. Depending on their nature, some substances may harm ecosystems, threaten biodiversity, and disrupt natural processes[2].

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), an agency within the U.S. Department of Labor, plays a big role in making sure workers have the right to a safe and healthy working environment. [3] OSHA’s mission is to require employers to create a workplace that is free of identified workplace health and safety hazards. OSHA also encourages workers to complain about conditions in the workplace for which their rights are believed to have been violated. Industries fall into distinct categories that follow rules to achieve compliance with the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSH Act). OSHA standards are found in Title 29 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) and are grouped by industry category, for example, General Industry, Construction, and etc.

Although OSHA’s framework assures the safety of domestic workers, international standards established by agencies like the International Labour Organization (ILO) enhance and support these efforts. U.S. agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) also play a big role in environmental and employee safety. Globally, other regulatory bodies, such as those in the European Union and Canada, offer comparative frameworks that ensure workplace safety and chemical regulation are harmonized across borders[4].

This chapter will examine the role of chemical regulation and policy, focusing particularly on chemical safety. It will examine the current legislation intended to protect the rights of workers and their health and outline areas that expose human life and the environment to risk due to chemical exposure.

II. Chemical Policies and Regulatory Frameworks

The increase in global chemical production has also resulted in the production of new materials and new substances, many of which are harmful threats to human health. To address these threats, international treaties were implemented as part of the solution. The Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants or POPs is one of these treaties. It was designed to provide a counter to the threats caused by persistent chemicals in the environment. The convention regulates about 29 POPs and endeavors to limit their production and application worldwide. [5] While the United States is not an active participant due to challenges in enforcement authority, it engages as an observer during conferences.

Another important accord is the Minamata Convention on Mercury, which was signed by the U.S. in 2013 after the catastrophic mercury pollution disaster in Minamata, Japan. The Minamata Convention was designed to lower worldwide mercury contamination by limiting mercury emissions from burning coal in power plants and industrial activities. [6] The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has designated mercury contamination a serious worldwide problem because the gas has the potential to be transported long distances through the air and water to distribute its toxicity.

The Basel Convention was founded in 1989 and manages hazardous waste. This international treaty addresses the transboundary movement of hazardous wastes and their disposal. It works towards safeguarding human and environmental well-being against the risks arising from waste mismanagement. The convention works towards reducing the generation of toxic waste, promoting sound disposal strategies, and fighting for responsible waste management worldwide. [7]

National Regulatory Agencies

On the national level, various regulatory bodies are responsible for managing chemical hazards and ensuring environmental protection. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is one of the most prominent agencies in this regard. Congress authorizes the EPA to develop regulations that implement environmental laws and ensure they are enforced effectively. The agency aims to protect human health and the environment by providing clean air, water, and land access.

One of the key regulations enforced by the EPA is the Clean Water Act (CWA), which aims to prevent the pollution of U.S. waters by controlling pollutant discharges from industries. The CWA was passed in 1948 and amended in 1972 to provide a system for regulating surface water quality and industries’ compliance with standards for controlling pollution. The EPA ensures compliance through enforcement by inspection, investigation, and monitoring. [8]

III. Major Chemical Regulations

The Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), enacted in 1976, is a key piece of U.S. legislation that confers upon the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) the authority to regulate a wide range of activities related to chemical substances. ¹ Through the TSCA, it grants the EPA the authority to mandate testing, reporting, and record-keeping for chemical substances. ² This enables the agency to gather crucial data on chemicals’ potential health and environmental effects. Based on this data, the EPA can continue to restrict the use of chemicals, including outright bans, if they pose an unreasonable risk to human health or the environment.

The Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) is a key component of U.S. chemical regulation. It empowers the EPA to identify, assess, and mitigate risks associated with chemical substances throughout their entire lifecycle. The EPA can mandate that companies report on the production and use of chemicals and maintain safety records. [9] The TSCA also allows the EPA to take enforcement action against companies that violate its regulations, including imposing fines and other penalties.9

The TSCA is a foundation of chemical regulation in the U.S. that equips the EPA to detect, determine, and limit the risks associated with chemical substances across their life cycle. The EPA can also mandate that firms submit the production and use of the chemical and keep safety records.

Additionally, the TSCA allows the EPA to take enforcement action against companies that violate its regulations, including imposing fines and other penalties.

In addition to the U.S. framework, the European Union has its chemical regulations. The European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) plays a important role in regulating chemicals through the REACH Regulation (Registration, Evaluation, Authorization, and Restriction of Chemicals). ³ Under REACH, manufacturers and importers must gather data on the properties of chemicals and register this information in a central database managed by the ECHA. ⁴ The rules are updated constantly to accommodate emerging scientific evidence so that chemicals can be used responsibly and safely.

Another principal regulation in chemical safety is the Clean Air Act, which outlines critical regulative requisites for safeguarding air quality. Originally established in 1955, the Clean Air Act has been thoroughly amended ⁵ in response to increasing concern about air contamination. It aims to protect the environment and human health from emissions that pollute outdoor or ambient air. The act requires the Environmental Protection Agency to create national standards for the lowest possible emissions levels and to leave responsibility for compliance to the states.

The act outlines measures to achieve compliance for areas that fail to meet these standards. It also sets federal standards for air pollution from mobile sources (such as vehicles) and their fuels and 187 hazardous air pollutants. Furthermore, the Clean Air Act introduced a cap-and-trade system to reduce emissions causing acid rain and established a comprehensive permitting system for significant sources of air pollution. The act also addresses pollution prevention in areas with clean air and includes provisions to protect the stratospheric ozone layer.

Federal legislation was introduced in 1955 before state and local governments mainly handled this air pollution. However, key amendments, particularly the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1970, greatly expanded the federal government’s involvement. These amendments introduced procedures for the EPA. This set national ambient air quality standards and required a 90% reduction in emissions from new automobiles by 1975, marking a big step forward in air pollution control.

Since its major revision in 1972, the Clean Water Act (CWA) has been a key piece of water quality regulation in the United States.[8] It holds industries accountable for wastewater discharge and defines enforceable standards to protect the environment and public health. As in the case of the Clean Air Act, the law granted the federal government the ability to regulate water pollutants, invest in wastewater infrastructure, and promote technological innovation and advances to improve water quality. The CWA aims to restore and preserve the country’s waters’ chemical, physical, and biological integrity. The legislation forbids the release of pollutants into open waters without a specific permit that establishes permissible pollution levels. This law was a leaving from the previously unregulated waste management system. The CWA established ambitious goals early on, including making all waters “fishable and swimmable” by 1983 and banning water pollution releases in 1985. Although these objectives weren’t complete, the CWA has played a big role in cleaning up many of the highly polluted waters and defending aquatic ecosystems by regulating industrial and municipal operations that might pose a risk to the environment and public health.

The Clean Water Act, in its current form, refers to the 1972 amendments to the Federal Water Pollution Control Act (FWPCA), which was originally passed in 1948.8 The FWPCA was the first federal law to address water pollution, providing funding to states and localities for research on pollution. However, it lacked the comprehensive federal oversight and clear pollutant limits that characterize the CWA.

One of the key provisions of the CWA is its requirement for states, territories, and tribes to develop and implement plans to uphold water quality standards (WQS). Based on pollution limits recommended by the EPA, the agency must review and approve these standards. WQS are not universal for all water bodies but are tailored to each body of water’s designated uses, such as protecting aquatic life, recreational activities, and public drinking water supplies.8

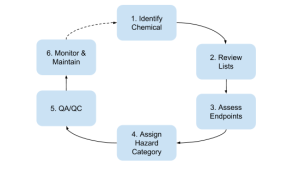

IV. Chemical Risk Assessment and Management

Risk assessment is a foundational element of chemical regulation, guiding decisions about the safe use of chemical substances. One of its primary components is hazard identification, which involves evaluating scientific evidence to determine whether a chemical can cause adverse health effects, such as cancer, congenital disabilities, or kidney damage, following either short-term or long-term exposure. [10]

Another key component is the dose-response assessment, which explores how varying levels of chemical exposure relate to changes in health outcomes. This process enables scientists to derive toxicity values—quantitative estimates of the exposure level at which health effects may begin to occur. These values are critical for comparing actual or estimated exposures to acceptable safety thresholds.

Risk assessments account for the route of exposure (inhalation, ingestion, dermal contact), duration, and intensity of exposure.1 Personal sampling provides the most accurate assessment of individual exposure, but it is often impractical. Consequently, environmental measurements—such as chemical concentrations in air, water, or soil—are frequently used as proxies to approximate human exposure.1 These assessments inform regulatory actions and help prevent harm to public health and the environment. This is how many of these policies and regulations look at to understand the underlying issue of some of these chemicals. As well as identify if they are too individual and to what extent.

V. Challenges in Chemical Regulation

The Growing Complexity of Modern Chemical Regulation

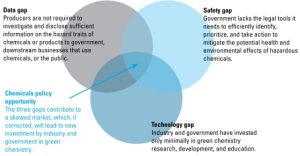

In the modern era, regulating chemicals has become increasingly complex. Scientific and industrial advancements continue introducing a vast array of new substances into commerce, often before their long-term health and environmental effects are fully understood. 1 Many chemicals are released into ecosystems and consumer products with minimal oversight, presenting significant regulatory challenges. Traditional frameworks often struggle to address emerging contaminants—particularly those with low-dose effects, cumulative exposures, or environmental persistence. 9

Recurrent data gaps, limited regulatory capacity, and disproportionate risks to vulnerable population segments exacerbate these challenges.[10] Delays in regulation or diluted responses also stem from lobbyism by industry and political pressures. [11] Fixing these system loopholes is necessary to increase public health protections and protect the environment in the face of increasing chemical complexity.

PFAS: A Persistent and Emerging Threat

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) exemplify the challenges of regulating emerging contaminants. First developed by 3M in 1938, PFAS gained widespread use by the 1950s due to their resistance to heat, water, and oil. [12]They became common in non-stick cookware, stain-resistant fabrics, and firefighting foams. However, as early as the 1970s, studies began linking PFAS exposure to serious health outcomes, including developmental delays, immune dysfunction, and certain cancers. 12

Despite limited regulation starting in the latter half of the 1990s, PFAS pervasively contaminates water, soil, and human tissues. Their persistence and toxicity have only continued to be confirmed by scientific consensus, and ongoing litigation has brought their long-held public health hazards into the spotlight. 12 Regulatory bodies are still under pressure to strengthen guidelines, prohibit high-risk PFAS substances, and clean up contaminated sites.12

Microplastics and Chemical Transport

Microplastics pose a second primary challenge to chemical regulation. They are plastic fragments that are less than 5 millimeters in diameter and are formed through the fragmentation of larger plastics and products such as exfoliants and cosmetics. [13] Today, microplastics are found across ecosystems—from oceans and rivers to soils and even human tissues. 2

Of particular concern is their role in transporting toxic chemicals like PFAS. Due to their hydrophobic surfaces, microplastics readily absorb environmental pollutants. 2 This enables them to act as vectors, distributing PFAS and other harmful substances throughout food chains.¹² Research has shown that this interaction may amplify the toxicity of both microplastics and the chemicals they carry.¹³Exposure in humans chiefly comes through ingestion, particularly through seafood, raising the issue of dietary exposure and long-term health impact.

Environmental and ecological implications

The global occurrence of microplastics and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) involves major environmental threats. Such contaminants can travel miles and last for decades while penetrating far-off ecosystems. Aquatics and wildlife on land are particularly vulnerable to a range of adverse effects that include blockages in the digestive system, hormonal imbalance, as well as harm to their reproductive systems. As these compounds accumulate in food chains and ecosystems, their long-term effects are also more complex to counter or effectively deal with.¹²

Challenges in Regulating Emerging Contaminants

The U.S. environmental regulatory system faces substantial challenges in addressing emerging contaminants like PFAS and microplastics. Many of these substances fall outside the scope of outdated legislation, including the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA). Designed initially to oversee chemical production and use, TSCA lacks strong provisions to restrict how hazardous substances are deployed in industrial or consumer contexts.¹³ Consequently, it has struggled to manage persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic chemicals.

Similarly, foundational regulations such as the Clean Water Act (CWA) and the Clean Air Act (CAA) emphasize pollution control through technology standards but often fail to keep pace with the innovation and proliferation of modern chemical compounds and plastics.¹⁴ These systems are not well-suited to manage new materials brought in many years after the legislation was passed, and there are gaps in environmental regulation.

Political and institutional reasons have also eroded the country’s capacity for regulation. Lobbying efforts by the industries have often postponed or watered down the imposition of controls on toxic substances.¹⁵ Meanwhile, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has consistently experienced budget deficits and staff constraints that limit its capacity to enforce regulation or strengthen safety standards in the face of new scientific evidence.¹⁶

One of the most dramatic demonstrations of regulatory inertia is the continued legal deployment of asbestos in the U.S. in defiance of overwhelming evidence of its cancer-causing properties, developmental toxicity, and genetic damage.¹⁷ Likewise, other toxicants, including a flame-retardant that interferes with the thyroid and fetal development and an industrial solvent that causes childhood cancer clusters, are still in use despite firmly established associated health risks.¹⁸

The effectiveness of environmental regulation also depends mostly on presidential administration priorities that establish the EPA’s ability to institute or enhance safeguarding measures. Presidential transitions generally result in changed policy agendas that strengthen or weaken environmental protections [19].

VI. The Role of the Public and NGOs

Public involvement plays a vital role in successful chemical regulation. Nonprofit organizations, communities, and citizens are essential in pushing for better protections, ensuring that regulatory agencies act responsibly, and pointing out chemical hazards that might otherwise not receive attention. Public comment periods are the simplest form of public involvement.

Regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) invite the public to provide input when new rules or rule changes are proposed. Public comment periods provide the opportunity for people and organizations to voice support, raise objections, or present scientific evidence to shape ultimate decisions¹. While technical expertise can strengthen a comment’s impact, grassroots voices are essential in signaling public concern and adding democratic legitimacy to regulatory processes.

Environmental advocacy organizations—such as the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), and local nonprofits—often act as intermediaries between scientific research and policy action. These NGOs perform autonomous studies, sue to force regulation and mount public pressure. They play a key role in advocating for transparency, unearthing regulatory shortcomings, and driving reforms like chemical safety revisions under the Lautenberg Chemical Safety Act.

In addition, citizen science and local monitoring efforts enable citizens to track chemical exposures in their communities. From water supply tests to air monitoring, these local efforts have made important information known—sometimes information that government agencies neglect or overlook. Community-based science empowers regulation, develops local capacity, and enforces environmental justice².

VII. Case Studies

There have been several cases where the essential role of public involvement and NGO advocacy in chemical regulation has happened. The most famous was the Flint Water Crisis, during which many were exposed due to regulatory failure. In 2014, Flint, Michigan, switched its water supply to the Flint River without implementing proper corrosion control measures. However, this lead from aging pipes entering the water system contaminates the city’s drinking water, even after repeated assurances from government officials that the water was safe. Many residents and independent researchers were committed to investigating the situation, as they noticed numerous health issues arising after the water system was changed. However, it wasn’t until pediatrician Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha presented data showing elevated lead levels in children’s blood that the issue gained widespread attention. Her research and continued advocacy from the community eventually led to action at both the state and federal levels. This crisis highlights the critical need for strong regulations and continuous monitoring to make sure drinking water safety. It also shows how crucial it is to evaluate the materials used in water infrastructure, as they can have long-term health impacts. In Flint, many children were exposed to harmful levels of lead—a toxic substance that has no safe level and causes irreversible neurological damage. The long-lasting effects of lead poisoning can include developmental delays, learning difficulties, and behavioral issues. Flint’s situation highlights the urgent need for stronger environmental health policies, better enforcement, and active community involvement to prevent similar disasters in the future.

Other cases studied that been done and can be seen as a challenge as well are PFAS (per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances). PFAS are another regulatory challenge where NGOs and the public have led the charge. These “forever chemicals,” used in products like non-stick cookware and firefighting foam, have been linked to cancer, immune suppression, and developmental issues. While federal regulation lagged for years, advocacy groups pushed for state-level bans and stricter standards, resulting in more aggressive action by the EPA starting in 20214.

Chemicals in Plastic. By UNEP, 2023, https://www.unep.org/topics/plastic-pollution/chemicals-plastics ©2023 by UNEP.

The asbestos regulation debate reflects the complexity of chemical policy. Although its health risks—particularly mesothelioma and lung cancer—are well known, asbestos is not entirely banned in the U.S. Public health advocates and NGOs have lobbied for decades for a complete ban, citing international precedent. Despite some restrictions, the EPA’s slow regulatory process and industry opposition have hindered comprehensive action5.

Conclusion

Chemical policy and regulation are essential for protecting our health and the environment from the dangers of harmful substances. As technology and industry advance, so do the challenges of managing the risks of producing, using, and disposing of chemicals. This is why, throughout the years, there have been both national and international regulations. These aim to monitor and limit the application of hazardous chemicals. Organizations such as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) implement legislation that ensures openness, accountability, and safety. But legislation alone cannot do the job.

The Flint Water Crisis shows that some of these issues can be overlooked and need to be addressed by other outside sources. Situations like this highlight the dangers of failing to enforce regulations and stress the need for policies backed by solid science.

As environmental challenges grow more urgent—from chemical pollution to climate change—the need for comprehensive, inclusive, and forward-looking chemical regulation becomes even more critical. Chemical regulation helps reduce harm and promotes fairness, especially for vulnerable communities more likely to face environmental risks. Governments, scientists, industries, and communities need to work together to build safer systems and ensure a healthier future.

Personal Statment

I wanted to do my research for this chapter on chemical policy and regulation because my understanding of the topic was minimal. I only knew that some chemicals were considered harmful, but I never really understood how or why certain chemicals were dangerous. I also knew little about the laws and regulations that help manage these risks. However, through my research, I’ve gained a deeper appreciation for the complexities of chemical safety and the systems in place to protect people and the environment.

One of the most eye-opening parts of my learning was discovering how chemicals are classified and labeled. Agencies like the U.S. Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) ensure that workplaces like construction sites and factories follow safety protocols. OSHA regulations require proper labeling and training so workers understand the dangers of the substances they’re handling. I learned that even basic labeling and safety data sheets are crucial for preventing accidents and long-term health issues.

I also encountered global efforts, such as international conventions and agreements that aim to reduce pollution and manage the use of toxic chemicals. These conventions bring leaders and advocates of countries together to protect the environment and public health. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) plays a huge role in the United States by conducting scientific research, assessing risks, and enforcing environmental laws. Their work helps limit the spread of harmful substances into our air, water, and soil.

This topic feels very personal because I live in Muscatine, Iowa, a community impacted by pollution. I remember a few years ago when a company on the south side of town faced a lawsuit due to the smoke, odor, and haze it released into the air. It affected surrounding neighborhoods, including mine. Over the years, another local company has been fined for polluting nearby water sources. These events made me realize how severe chemical exposure can be—and how much communities rely on regulatory agencies to hold polluters accountable.

Learning about these issues has inspired me to be more engaged and informed about environmental justice. Marginalized communities often live closest to industrial facilities and have a higher risk of chemical exposure. Through this research, I now see the importance of policies limiting pollution and supporting the health and rights of vulnerable populations. I hope to use this knowledge to advocate for stronger protections, better transparency, and more equitable enforcement of environmental laws—so that all communities, regardless of income or location, can live in a safe and healthy environment.

Reference

[1] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Chemical Hazards,” www.cdc.gov, May 22, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/learning/safetyculturehc/module-2/5.html.

[2] Xingyu Li et al., “Comprehensive Review of Emerging Contaminants: Detection Technologies, Environmental Impact, and Management Strategies,” Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 278 (May 2, 2024): 116420–20, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.116420.

[3] U.S. Department Of Labor, “1910.1 – Purpose and Scope. | Occupational Safety and Health Administration,” Osha.gov, 2020, https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/1910/1910.1.

[4] European Commission, “REACH Regulation,” environment.ec.europa.eu, 2023, https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/chemicals/reach-regulation_en.

[5] Office of Environmental Quality, “Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants,” United States Department of State, n.d., https://www.state.gov/key-topics-office-of-environmental-quality-and-transboundary-issues/stockholm-convention-on-persistent-organic-pollutants/.

[6] US EPA, OITA, “Minamata Convention on Mercury | US EPA,” US EPA, February 24, 2014, https://www.epa.gov/international-cooperation/minamata-convention-mercury.

[7] Basel Convention, “Basel Convention > the Convention > Overview,” www.basel.int, 2011, https://www.basel.int/TheConvention/Overview/tabid/1271/Default.aspx.

[8] US EPA, “Summary of the Clean Water Act,” United States Environmental Protection Agency, June 12, 2024, https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-clean-water-act.

[9] US EPA, OECA, “Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) Compliance Monitoring | US EPA,” US EPA, July 10, 2013, https://www.epa.gov/compliance/toxic-substances-control-act-tsca-compliance-monitoring.

[10] FEMA, “4.2. Risk Assessment Overview | FEMA.gov,” www.fema.gov, February 21, 2024, https://www.fema.gov/oet-tools/chemical-incident-consequence-management/4/2.

[11] Inci Sayki, “Chemical Industry Spent Millions Lobbying against Regulation of Toxic Substances,” Truthout, April 8, 2023, https://truthout.org/articles/chemical-industry-spent-millions-lobbying-against-regulation-of-toxic-substances/.

[12] Jocelyn C Lee et al., “Research Progress in Current and Emerging Issues of PFASs’ Global Impact: Long-Term Health Effects and Governance of Food Systems,” Foods 14, no. 6 (March 11, 2025): 958–58, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14060958.

[13] Robert W. Adler and Carina E. Wells, “PLASTICS and the LIMITS of U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL LAW,” PLASTICS and the LIMITS of U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL LAW, 2023.