19 Impacts and Environmental Challenges On National-Level

When it comes to climate change and global warming, the first issue that comes to my mind now is my pet turtle, Xiaojin (little gold). Xiaojin is a yellow-ringed shell turtle and has a natural habit of hibernation. Every autumn, it will reduce its diet and activities, getting ready to enter hibernation. Then I will prepare it with insulation and moisture-retaining materials for hibernation. In order to ensure the quality of its hibernation and thereby enhance its immunity and health, I do not control the temperature but let it hibernate at the natural temperature. Hibernation usually lasts from November of the previous year to April of the following year. But now a problem has emerged, that is, the global temperature is rising day by day. XiaoJin, who usually only showed signs of waking up in March, actually woke up in February this year. This is because my hometown has experienced an early high-temperature climate that has never been seen before but has been occurring frequently year by year. At the beginning of February, the highest temperature could reach 30 degrees Celsius for several days (usually around 10 degrees Celsius). That day, Xiaojin’s awakening surprised all the family members because it shouldn’t have woken up so early. Although pet turtles look hard on the outside, in fact, their stomachs are very fragile and their immunity is low when they just wake up from hibernation. If they wake up at the wrong time and the temperature drops sharply again before all their organs can adapt, there is a high risk of getting sick or even dying. Fortunately, in the end, we placed the hibernation box in a constant-temperature indoor area, allowing it to get through this crisis. But I can’t help thinking that if domestic pets that need to hibernate can receive human assistance due to the problem of global warming, then what about the hundreds of millions of species of wild animals and plants in the wild? When the climate changes too fast and they can’t make quick changes, is it a disaster for a group of animals and plants? This experience strengthened my eagerness to alleviate and solve the serious problem of global warming, making me pay more attention to and attach greater importance to this issue. And this time, I happened to have the opportunity to write down this story and my thoughts. Therefore, I decided to take this opportunity to do relevant research well to enhance my understanding of the problems of global climate change and temperature rise.(LZ)

In the previous chapter, my co-author Abigail Zimmerman provided a comprehensive scientific basis for understanding climate change, clarifying the mechanism of the greenhouse effect, the role of anthropic greenhouse gas emissions, and the chain environmental consequences ranging from global temperature rise and extreme weather events to biodiversity loss and ocean acidification. She further explored mitigation strategies, emphasizing the urgency of achieving net-zero emissions through carbon reduction, innovative clearance technologies and systematic social transformation. Based on this scientific framework, my part will shift the focus to the national context of the United States, studying its role as a historical and contemporary emitter, the impact of climate-driven disasters on public health, and the complex interaction of federal and state policies. I analyzed the differences in regional vulnerabilities, such as coastal flooding, agricultural instability and air quality crises, while criticizing the gap between ambitious climate goals and fragmented policy implementation. By integrating health equity into climate governance, this section emphasizes the need to combine global responsibility with national-level and more detailed localized solutions.(LZ)

First, let’s take a look at the greenhouse gas emission data. The United States remains a major emitter globally, and carbon dioxide emissions in certain industries are still increasing. The latest report from the US Environmental Protection Agency shows that during the period from 2021 to 2022, carbon emissions in the United States increased by 1%. The main reason is that the use of fossil fuels is not significantly reduced (EPA, 2023. This indicates that even as clean technologies continue to develop, it is not easy to truly achieve the emission reduction targets.(LZ)

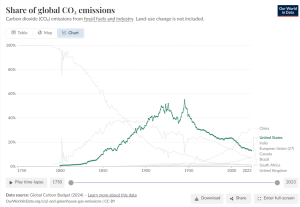

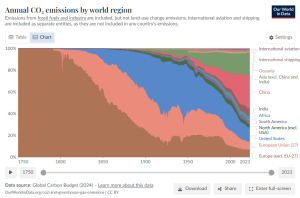

Being included in the global framework, in 2022, the United States accounts for about 14% of all CO ₂ emissions (global carbon budget, 2024). In contrast, China’s emissions are about 29%, and the European Union’s total emissions are about 7% (Our World In Data, 2024) These differences indicate that although the United States is by no means the largest single emitter, it is still one of the largest emitters globally. America’s per capita emissions are also greater than those produced by China and the European Union (Our World in Data, 2017).(LZ, ARZ)

As a student majoring in public health, I find it astonishing that the national emissions profile is influenced not only by total output but also by historical responsibilities. Since the Industrial Revolution, the United States has cumulatively emitted more carbon dioxide than any other country, accounting for nearly a quarter of the total emissions to date, while China, despite the recent surge, accounts for only about one-eighth of historical emissions (Our World in Data, 2017). This long-term industrialization background has led to a higher baseline for atmospheric carbon dioxide and highlights why the United States’ leadership in mitigation is ethically and scientifically important.(LZ, ARZ)

However, merely focusing on the percentages of global statistics might overlook regional dynamics. North America as a whole, dominated by the United States, makes up about a quarter of all the world’s carbon dioxide emissions every year, second only to Asia (China’s leading) (Our worldin Data, 2024). In this region, the intensity of emissions varies: Canada’s per capita emissions are comparable to those of the United States, while Mexico’s per capita emissions are much lower. These internal contrasts highlight that the policy choices of the United States have set the tone for the entire European continent.(LZ, ARZ)

When studying international climate financing, I have learned that the United States has also provided a large amount of funds for adaptation and mitigation projects in developing countries – these resources are designed to compensate for the disproportionate historical emissions (UNFCCC. 2023). However, despite the flow of billions of dollars through mechanisms such as the Green Climate Fund, questions remain about how these funds can effectively benefit vulnerable communities and whether they are linked to stronger domestic emission reduction efforts.(LZ)

Reflecting on this global positioning, I realize that the combined role of the United States – the current major emitter, the largest emitter in history and a major climate finance provider – has created both responsibilities and opportunities. Morally, the United States must promote innovation in the field of clean energy and support international equity. Meanwhile, domestic policies can also have a chain reaction abroad: When the United States raises energy efficiency standards for automobiles or invests in grid resilience, it sets benchmarks that other countries usually follow.(LZ)

However, transforming global leadership into local health outcomes is no easy task. For instance, in my hometown, the increase in ozone levels caused by emissions from regional coal-fired power plants has exacerbated the incidence of asthma in low-income communities. Although the per capita emissions of these communities are far lower than the national average, they bear a disproportionate burden. The disconnect between national percentages and actual experience explains why public health must be incorporated into climate policy design.(LZ)

Furthermore, the United States’ ambitious net-zero target, with the goal to be reached in the middle of this century (President Biden’s commitment by 2050), requires an unprecedented expansion of renewable energy capacity and carbon removal. However, the current federal and state policies have not yet been coordinated to narrow the remaining gap. For instance, only a few states have binding medium-term emission reduction targets, and the majority of states lack coherent plans to address historical inequalities or fund community adaptation. Without a cohesive national framework, the efforts of states and localities run the risk of duplication, or worse, leaving some regions behind.(LZ, ARZ)

In order to build a bridge between the global and local levels, I believe that public health professionals must bring the voices of the community into international forums. Local health indicators – such as the hospitalization rate for heat-related diseases – should inform national commitments. By integrating health indicators into global negotiations and domestic implementation, we can ensure that emission targets are translated into tangible health benefits.(LZ, ARZ)

The direct impact of climate change on health is no longer hidden in the future – today’s soaring temperatures and deteriorating air quality are obvious. Nearly half of Americans – 156.1 million people – live in counties with unhealthy ozone or particulate pollution as reported in the “State of the Air 2025” report, despite decades of efforts to reduce emissions (American Lung Association, 2025).These fine particles (PM₂.₅) and ground-level ozone penetrate deep into the lungs and bloodstream, triggering an increased risk of asthma attacks, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease attacks, heart attacks and strokes (EPA, 2024). This persistent air pollution is a chronic burden – even if the smoke from wildfires does not reach the city center, there will be a seasonal surge in the number of respiratory hospitalizations in hospitals.(LZ)

However, when wildfires rage, this burden will rise sharply. Last year’s long wildfire season in California produced thousands of miles of smoke, which was associated with a sharp increase in emergency room visits due to respiratory distress in multiple states (EPA, 2023).Scientific research has confirmed that exposure to wildfire smoke can exacerbate asthma and bronchitis in vulnerable populations and even lead to premature death (EPA, 2024). As a researcher of public health, I have found it astonishing that these accidental incidents not only overwhelm emergency services but also lead to a long-term decline in lung function among people who are repeatedly exposed to them.(LZ)

Edelson, J. (2020, September 8). Home is engulfed in flames during the Creek Fire in the Tollhouse area of California’s unincorporated Fresno County. Getty Images.

What makes the problem more complicated is that extreme high-temperature events have become more frequent and intense. During the warm season months of 2023 (May to September), the rate of emergency room visits related to high temperatures rose significantly in several regions of the United States, especially among males and adults aged 18 to 64 (CDC, 2023). High temperatures are now the leading cause of weather-related deaths, claiming more than 1,200 lives each year (NOAA, 2024). From the perspective of the health system, these heat waves have weakened the resources of the emergency medical system, forced cooling centers to be activated, and highlighted unfairness – low-income groups and the elderly often lack adequate air conditioning or have no access to cooling facilities.(LZ)

Given these trends, it is obvious that the climate-driven environmental health impacts require a comprehensive response. Traditional air quality management rooted in national environmental air quality standards has successfully reduced PM 2. 5. Since 2000, it has decreased by more than one-third, and ozone has decreased by 17% (EPA, 2024) However, these overall increases mask the persistent hotspots where emission sources remain unregulated and extreme high temperatures have exacerbated baseline pollution. It is precisely in these communities (usually low-income urban communities) that public health intervention measures, such as air filtration programs in schools and targeted high-temperature alert information, can have a huge impact.(LZ, ARZ)

In addition to emergency care, the harm caused by recurrent smoke and high temperatures to mental health cannot be ignored either. The Fourth National Climate Assessment emphasizes that climate change undermines mental health through anxiety, trauma from disaster exposure and the stress of repeated evacuations (USGCRP, 2018). As a student, I recognize that recovery strategies must include psychosocial support, such as mobile clinics that provide asthma treatment and counseling after a fire incident to meet comprehensive health needs.(LZ, ARZ)

To summarize here, the impact of climate change on environmental health at the national level is multi-faceted: chronic air pollution, occasional wildfire smoke and escalating heat waves come together to overwhelm the health system and exacerbate inequality. Although regulatory success has reduced the average pollutant levels, extreme weather has eroded these achievements and caused new public health emergencies. Looking to the future, my reflection is that cross-departmental cooperation – combining environmental regulation, emergency preparedness and community-based health intervention measures – is needed to protect people from the dual threats of climate change and air quality degradation.(LZ, ARZ)

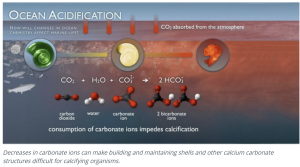

After conducting more research and exploration, I found that the situation in coastal cities is also not optimistic. Due to the dual pressure of land subsidence and sea level rise, places such as New York and Charleston have to spend billions of dollars every year to deal with floods (Shirzaei et al., 2025). Meanwhile, ocean acidification is quietly undermining the livelihoods of coastal fishermen as the ocean absorbs excessive carbon dioxide, making the seawater more acidic and threatening key industries. For instance, the lobster industry in Maine has been severely affected (NOAA Fisheries, 2023).(LZ)

NOAA. (2023). Ocean Acidification and Fisheries Impact. www.noaa.gov

Similarly, in major agricultural states, the outlook is equally worrying. Farmers in Iowa now have to struggle with continuous heavy rain and drought, forcing the corn planting cycle to be constantly adjusted (USDA, 2024). This unpredictable pattern not only threatens output but also has the potential to prompt rural population migration, which could fundamentally change the demographic structure of the entire Midwest.(LZ)

In addition to these regional snapshots, coastal subsidence and sea level rise have jointly magnified the flood risk and exacerbated the health problems of vulnerable communities. In New York City, more than 60% of the residents live in coastal counties, where high tide floods and extreme storms have pushed the sewage system to the brink. In 2010, the New York State Sea Level Rise Working Group estimated that upgrading urban sewage infrastructure alone could cost 36.2 billion US dollars within 20 years (New York State Sea Level Rise Working Group, 2015). These overburdened systems may allow pollution to enter drinking water, leading to gastrointestinal diseases, and the chronic stress of repeatedly damaging sanitation facilities adds a mental health burden to the affected population.(LZ)

In Charleston, South Carolina, tidal flood events – which used to occur only two to three “king tides” each year – now occur on average 11 times, and by 2045, there could be nearly 180 floods each year (Charleston City, 2015). Due to the flood bringing sewage and industrial pollutants into the community, skin infections, diarrheal diseases and asthma in low-lying areas have intensified. This sharp increase has put pressure on emergency services and health care facilities.(LZ)

Meanwhile, ocean acidification continues to quietly damage the Marine ecosystems that maintain coastal nutrition and economy. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s fisheries report, “Understanding Ocean Acidification,” emphasizes that shellfish larvae in Maine and Massachusetts deform under acidic conditions, leading to a decline in fish populations and an annual loss of over one billion US dollars in the fisheries market (NOAA Fisheries, 2023). This forces communities to import less healthy seafood substitutes, increasing the risk of foodborne diseases and diet-related chronic diseases.(LZ)

When it comes to familiar physical and mental health issues again, these environmental influences go far beyond physical diseases. Repeated floods and ecosystem loss have exacerbated chronic stress and mental health disorders. In the Big Swamp near Charleston, community surveys show that nearly a quarter of adults reported moderate to severe depressive symptoms after repeated “annoying floods”, but access to counseling and mental care remains scarce (Charleston, 2015). This highlights how ecological degradation harms physical and mental health.(LZ)

Turning the topic to the central region of the United States, the unpredictable weather patterns in the Midwest – spring heavy rains causing delays in planting, followed by summer droughts – illustrate the socio-economic impact of climate change on agriculture. The Midwest Climate Center of the United States Department of Agriculture predicts that without effective adaptation measures, arid regions could expand by 30% by the summer of 2050 (USDA, 2024). Although large farms invest in drought-resistant hybrid crops and precision irrigation, small-scale producers often lack funds, widening the economic gap in rural areas.(LZ)

The economic analysis of the U.S. Farmland Trust warns that due to rising temperatures and changes in rainfall patterns, 80% of farmland in the United States may be at risk (U.S. Farmland Trust, 2023). These threats endanger rural livelihoods, forcing younger residents to seek stable jobs in urban areas, while the elderly population has difficulty supporting community health infrastructure. With the closure of schools and clinics, local health departments are facing shortages of budgets and personnel, which is not conducive to preventive health care and chronic disease management.(LZ)

The Midwest chapter of the Fifth National Climate Assessment highlights that climate-smart agricultural practices – covering crops, conservation tillage, and diverse crop rotation – can mitigate soil erosion and enhance resilience, but their adoption remains uneven (USGCRP, 2023). Promotion services and cooperatives play a key role in knowledge transfer, but the constantly decreasing county budget hinders the funding of projects. If no significant investment is made in technology and community outreach, the rural health gap related to agricultural instability may deepen, thereby leading to an increase in the incidence of cardiovascular diseases and diabetes related to food insecurity.(LZ)

The migration of the population to the upper Midwest due to climatic reasons further complicates the situation. People who call themselves “mountaineers” seek a cool climate and reliable water supply near the Great Lakes. The towns they reach have limited sanitation and social services (Kallmorris, 2023). Although such immigration can revitalize the local economy, it may also overwhelm medical institutions that are already overburdened due to an aging population. Newcomers need to understand the health system and social networks, which is a task that clinics and community organizations with insufficient resources find difficult to accomplish.(LZ)

In addition to the direct impact on agriculture, the macroeconomic shock brought about by weather disasters will also affect food prices across the country. After the 2019 Mississippi River Basin floods, the United States Department of Agriculture estimated losses of crops and livestock to reach 2 billion US dollars, which dealt a blow to low-income urban families that relied on affordable groceries (USDA, 2022). This indicates that rural climate vulnerability affects the entire food supply chain and has a serious public health and nutrition impact on the food-insecure population.(LZ)

Dealing with these complex challenges requires an integrated strategy that combines the environmental and socio-economic fields. Federal initiatives such as the Rural Assistance Grants from the United States Department of Agriculture and the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s funds for building disaster-resistant infrastructure and communities have provided the necessary resources for upgrading rural water supply systems and flood clinics, but these grants often exceed the capacity of small towns. Public health professionals and students like us can enhance proposals by assisting with grant applications and conducting community health needs assessments.(LZ, ARZ)

The core of all these methods is the role of community participation. Public health practitioners should consider collaborating with farmers to jointly design heat stress protocols, integrate air quality sensors into school curricula near industrial operations, and formulate joint emergency response plans for health and agriculture. In coastal areas, health educators, in collaboration with fishermen, can monitor the safety of seafood during acidification events and provide real-time alerts to protect livelihoods and public health. I’m just mentioning the community aspect here. My teammates will conduct more detailed research based on the local level in the next chapter of the article.(LZ)

Finally, before moving on to the next part of the research, I would like to make a small summary of this part. The impact of climate change on environmental health at the national level – from coastal flooding and ocean acidification to agricultural fluctuations and population migration – constitutes a multi-faceted public health crisis. Although those targeted citations laid the foundation for this discussion, the broader narrative emphasized the necessity of integrating policy, technology and grassroots actions. As a student majoring in public health, I believe there is an urgent need for cross-departmental collaboration: streamlining federal funds, state authorization to integrate health assessments, and community-driven initiatives to empower residents. Only through such comprehensive participation can the United States address the challenges intertwined with environmental deterioration and socio-economic chaos, and pave the way for building healthier and more resilient communities.(LZ)

Next, I will conduct research and some analyses in the field of environmental-related policies within the United States. Although I personally sometimes think that issues related to policies and laws are very dull and boring, this is a very important field. Under reasonable policy management, it can make significant contributions to improving the environmental problems it is facing. In terms of policy, although the federal government has introduced clean energy subsidy policies such as the Inflation Reduction Act (EPA, 2023), their implementation is full of difficulties. Last year, in West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency, the Supreme Court ruled that under the Clean Air Act, the Environmental Protection Agency has no authority to force power plants to reduce carbon emissions through extensive “generation transfer” directives, which significantly limits the agency’s regulatory scope (Supreme Court, 2022). Meanwhile, the other efforts of the federal government – including small grants for environmental justice and expanded methane regulation – are moving forward, but they are facing persistent legal and political resistance. The EPA’s own model shows that, based on the current spending trajectory of the IRA, the carbon dioxide emissions of the US power sector could still be reduced by 49% to 83% by 2030 compared to the 2005 level (EPA, 2023) [Investopedia, 2023]. However, these predictions assume that there are no further legal challenges or financial changes, and therefore the public health benefits are uncertain.(LZ, ARZ)

Fuel Cells Works. (2025, January 29). Toyota Motor

In addition to the measures of the federal government, the responses of the states also showed obvious diversity. I noticed earlier that California took the lead in actively promoting zero-emission transportation by issuing Executive Order B-48-18, which set a goal of putting 5 million zero-emission vehicles on California’s roads by 2030. And it is required that 250,000 public chargers (including 10,000 DC fast chargers) and 200 hydrogen refueling stations be installed by 2025 (Executive Order B-48-18, 2018). Although this policy aligns with the state’s low-carbon fuel standards and the requirement and aspiration for 100% clean electricity, it has raised concerns about the affordability of cars and the fairness of the distribution of charging infrastructure in low-income and rural communities. In contrast, Texas mainly relies on market incentives and abundant wind energy resources: In 2022, wind energy accounted for 27% of the state’s power generation, the highest among all states in the United States (EIA, 2023). However, due to the lack of complementary demand response plans or targeted industrial emission regulations, wind power construction in Texas has had little effect on reducing pollutants in the transportation or heavy industry sectors, thus imposing a disproportionate burden on frontline residents.(LZ)

Despite these examples of leadership, many regions are underserved due to the lack of a unified national framework. The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) has demonstrated the role of key carbon pricing mechanisms: since its launch, the 10 participating countries have reduced carbon dioxide emissions in the power sector by more than 50% while their GDP has continued to grow, and have invested over 8.6 billion US dollars in energy efficiency and renewable energy (RGGI Benefits Report, 2021). However, the upper limit of RGGI only applies to generators, and heating, transportation and industrial emissions are largely unregulated. Similarly, the Western Climate Initiative spans multiple Western states and Canadian provinces, but lacks consistent implementation and fair terms. This chaotic situation has forced public health advocates to engage in sporadic battles, such as protecting air monitoring networks here or community solar projects there, rather than taking comprehensive intervention measures that combine environmental benefits with health equity outcomes.(LZ)

Given these regulatory challenges, effectively protecting public health in the face of climate-driven hazards clearly requires multi-level coordination. Federal agencies must re-establish regulatory powers – possibly through new legislation, such as strengthening the Clean Air Act – and explicitly require that the impact on health be considered in cost-benefit analyses. Countries should combine ambitious sectoral goals (electricity, transportation, heating) with cross-sectoral policies aimed at reducing common pollutants, such as aligning clean truck rules with standard pollutant standards to protect communities near freight corridors. Then, local governments can adjust these extensive policies by establishing localized emission inventories, community health needs assessments, and participatory decision-making channels centered on front-line voices. Only through this hierarchical and health-centered regulatory framework can the United States translate climate investment into cleaner air, greater safety, fewer extreme environments and fair health benefits for all.(LZ, ARZ)

All in all, my analysis and research highlight the multi-faceted climate challenges faced by the United States, ranging from its disproportionate historical emissions to the escalating health burden borne by marginalized communities. Despite the progress made in regulation, persistent policy disconnections, such as legal obstacles to federal emissions regulations and imbalances in state-level commitments, have hindered coordinated actions. Coastal erosion, agricultural fluctuations and systemic inequality require a comprehensive strategy, with public health given priority in climate adaptation. The struggles of these countries have highlighted the urgency of combining global leadership with grassroots resilience. In the following section, my co-author Farah Haider will delve into the crucial role of state and local governments in addressing climate change, taking Iowa as an example to explore the tensions between renewable energy initiatives, agricultural adaptation, and economic priorities and environmental management. Stay tuned!(LZ, ARZ)

References

EPA. (2023). Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/inventory-us-greenhouse-gas-emissions-and-sinks

Global Carbon Budget. (2024). Share of global CO₂ emissions. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/annual-share-of-co2-emissions

Our World in Data. (2017). Per capita CO₂ emissions. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/per-capita-co2

Our World in Data. (2024). CO₂ emissions by country. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions

Our World in Data. (2017). Contributed most to global CO₂ emissions. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/contributed-most-global-co2

UNFCCC. (2023). Submission to the first global stocktake under mandate: Global Carbon Budget. Retrieved from https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/202303061935—GCP%20GST%20submission%20letter%20FINAL%20Feb%202023.pdf

Edelson, J. (2020, September 8). Home is engulfed in flames during the Creek Fire in the Tollhouse area of California’s unincorporated Fresno County [Photograph]. Getty Images. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/severe-wildfires-raise-the-chance-for-future-monstrous-blazes/

EPA. (2023). Health Effects Attributed to Wildfire Smoke. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/wildfire-smoke-course/health-effects-attributed-wildfire-smoke

EPA. (2024). Our Nation’s Air 2024: A look back at combined ozone and PM₂.₅. Retrieved from https://gispub.epa.gov/air/trendsreport/2024/

EPA. (2024). Estimating PM₂.₅- and Ozone-Attributable Health Benefits. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2024-06/estimating-pm2.5-and-ozone-attributable-health-benefits-tsd-2024.pdf

NOAA. (2024). HEAT.gov – National Integrated Heat Health Information System. Retrieved from https://www.noaa.gov/heatgov-national-integrated-heat-health-information-system

USGCRP. (2018). Chapter 14: Human Health. In Fourth National Climate Assessment. Retrieved from https://nca2018.globalchange.gov/chapter/14/

American Farmland Trust. (2023). Report predicts climate change could drastically impact corn acres. Radio Iowa. https://www.radioiowa.com/2023/04/20/report-predicts-climate-change-could-drastically-impact-corn-acres/

City of Charleston. (2015). Sea Level Rise Strategy Plan. https://www.charleston-sc.gov/DocumentCenter/View/10089/12_21_15_Sea-Level-Strategy_v2_reduce?bidId=

Kallmorris. (2023). Climigrants: Mass Migration to the Midwest Amongst Climate Change. https://www.kallmorris.com/columns/climigrants-mass-migration-to-the-midwest-amongst-climate-change

New York State Sea Level Rise Task Force. (2015). Report of the New York State Sea Level Rise Task Force. https://dos.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2020/09/nys-sea-level-rise-task-force-report.pdf

NOAA Fisheries. (2023). Understanding Ocean Acidification. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/insight/understanding-ocean-acidification

Shirzaei, M., et al. (2025). 13 coastal cities in the US that are slowly sinking. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/us-coastal-cities-sinking-subsidence-flood-risk-2025-5

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). (2024). Climate Change Impacts on Iowa Agriculture. https://www.climatehubs.usda.gov/sites/default/files/Climate%20Change%20Impacts%20on%20Iowa%20Agriculture_3.pdf

U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP). (2023). Fifth National Climate Assessment: Chapter 24, Midwest. https://nca2023.globalchange.gov/chapter/24

Executive Order B-48-18. (2018, January 26). California Governor’s Proclamation. California Secretary of State. https://www.library.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/GovernmentPublications/executive-order-proclamation/39-B-48-18

EIA. (2023, December 15). Texas generated more electricity from wind than any U.S. state in 2022. U.S. Energy Information Administration. https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=52319

RGGI Proceeds Report. (2021). The investment of RGGI proceeds in 2021. Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. https://www.rggi.org/sites

EPA. (2023). Summary of Inflation Reduction Act provisions related to renewable energy. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/green-power-markets/summary-inflation-reduction-act-provisions-related-renewable-energy

Supreme Court. (2022). West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/21pdf/20-1530_n758.pdf

Fuel Cells Works. (2025, January 29). Toyota Motor Europe partners with Hydrogen Refueling Solutions and ENGIE for a fast and cost-efficient hydrogen refuelling infrastructure [Photograph]. https://fuelcellsworks.com/2025/01/29/fuel-cells/toyota-motor-europe-partners-with-hydrogen-refueling-solutions-and-engie-for-a-fast-and-cost-efficient-hydrogen-refuelling-infrastructure