26 Food Accessibility

cpknipper

Personal Statement: Why I chose food accessibility?

Having the ability to have access to a healthy diet is a privilege that not many people understand. Growing up, I never really thought about how different life can be for others when it comes to getting good food. But as I learned more, I realized that people around the world face all kinds of situations that make it tough to eat healthily. Some live in areas with no grocery stores nearby, while others can’t afford fresh food. It hit me that these differences aren’t just small inconveniences, they really shape people’s lives. That’s why I wanted to dig into this topic for my paper.

There are so many reasons why people struggle to get healthy food, and it’s not just one thing. Money is a big issue; if you fall into the lower-income sector, buying fresh fruits and veggies isn’t easy. Then there’s stuff like not having a car to get to a store or living somewhere where good food just isn’t available. Things like government policies or unfair systems can make it even harder, especially for certain groups. I got curious about which of these factors hit people the hardest and how they differ depending on where you live.

For this paper, I wanted to figure out what’s really going on with food access around the world and what people can do about it. I looked at different places and tried to understand what’s stopping people from eating well and what solutions might actually work. Writing this helped me see how complicated this problem is, but also how important it is to keep working toward answers. I hope my research sheds light on what’s happening and maybe even inspires some ideas for change.

Food Accessibility

Many adverse health outcomes stem from the diverse types of food that people consume in their daily lives. Just as there are healthy foods that have been proven to be beneficial to your body’s well-being, there are just as many food products that hinder the natural processes that your body carries out every single day. Whether it is the amount of food you consume or the quality of food you consume, it all influences your body even if you do not notice an immediate difference.

Having access to enough food to support an active and healthy lifestyle is pronounced as the term known as food security. Nutrition insecurity is the ability to have consistent access, availability, and affordability of foods and beverages that promote well-being and prevent disease (NIH, 2022). These two definitions affect individuals on all levels, all the way from individual households to public health as a whole. Lack of access to healthy and affordable food increases your risk of certain health conditions including diabetes, obesity, and heart disease among other chronic diseases.

Looking at accessibility at the global level, food scarcity is more complex than just not having access to affordable and nutritious food. A complex number of underlying issues have a significant effect that does not go unnoticed. Some of which consist of poverty, conflict, climate change, and inadequate infrastructure (Medical Ambassadors, 2024). Communities that fall under the impoverish category lack the financial resources to purchase healthier foods causing a consistent cycle of malnutrition and hunger that becomes hard to break free from. These communities tend to have more infrastructure disadvantages than those of individuals who live in wealthier communities. Transportation networks are essential for the transportation of food to markets and from the market to the consumer. This is most common in developing or rural areas where roads may be damaged or unpaved and sometimes not even existent. Not having these means of transportation affects the price of food as it makes transportation costs more expensive which results in the simultaneous increase of the actual food prices. Neighborhoods that fall into this low-income category have been labeled as “food deserts” due to not living in a location where supermarkets or other places where healthy affordable food is accessible (Ver Ploeg, 2010). These individuals do not have any another option but to rely on smaller neighborhood stores that may not carry healthy options, or if they do, they have price points that are not affordable to the common middle-class person.

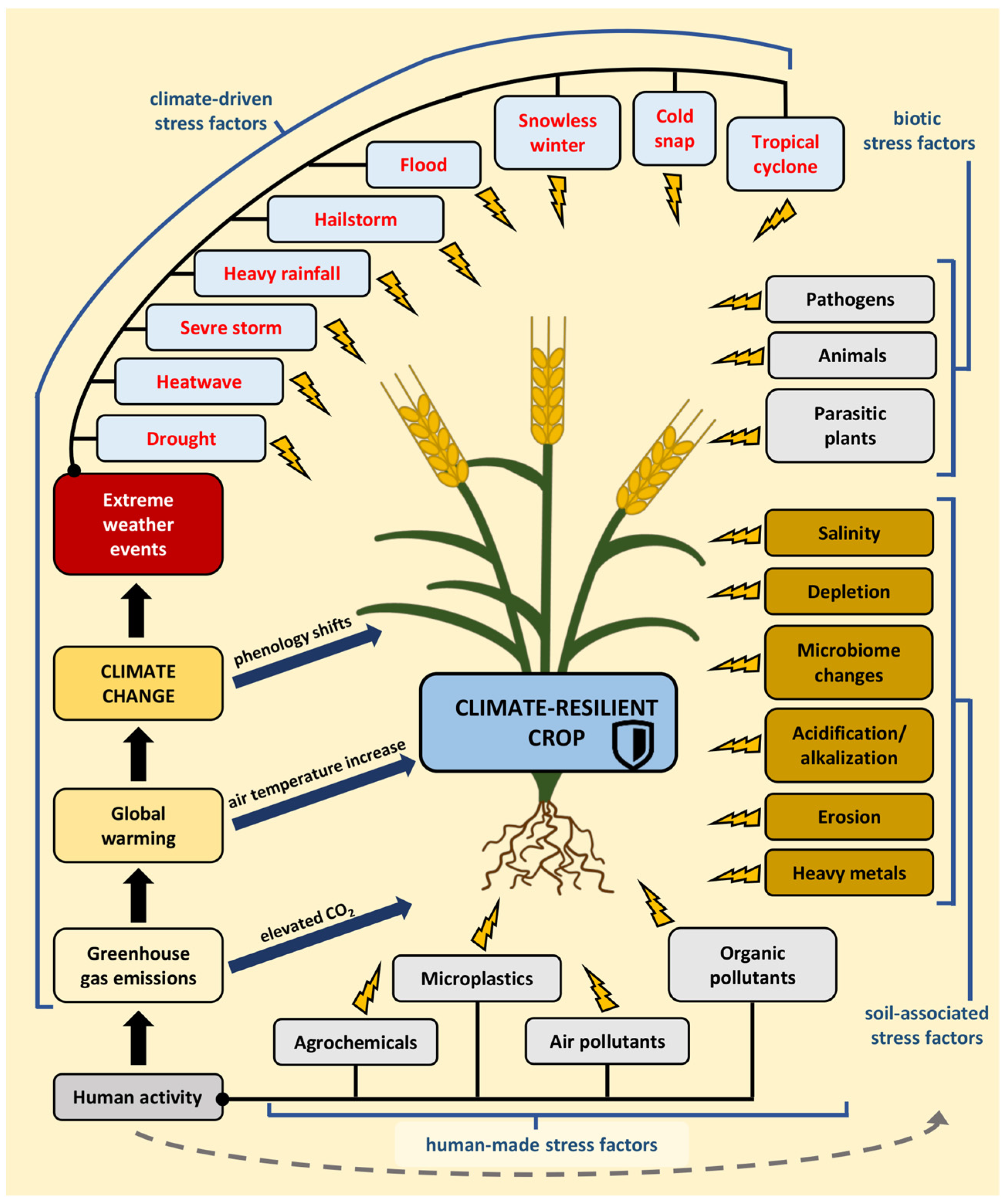

Climate Change

The impact climate change has on food accessibility around the world is harsh and if you happen to fall into the low-income category of the population, these effects are more extensive. Rising temperatures and unpredictable weather patterns are interfering with agricultural practices which are causing crop failures and food shortages. Farmers have experienced climate change effects for a long time, and these factors, and their simultaneous effects have only gotten worse. Agriculture and climate change are linked by the changes in weather patterns and temperatures (Chandler, 2023). The Earth’s temperature is rising at an unprecedented rate, directly affecting agricultural production and those who depend on it for their livelihood. Over the last two decades, the world has experienced the warmest temperatures since the 1800s, temperatures rising above the pre-industrial level by 1.1 degrees Celsius, much of which is from emissions released globally.

Smallholder farmers, individuals who raise crops and livestock on a smaller scale, are prone to experiencing these climate effects first and more drastically than others. To maintain their lifestyle and make a living, farmers need healthy land and reliable weather patterns. With these climbing temperatures and shifting growing seasons, it is becoming harder for farmers to maintain stable crop yields and adapt to unpredictable weather conditions. There are more frequent intense periods of rainfall, followed by flooding and more prolonged periods of drought where rain does not appear for long stretches of time (Chandler, 2023). For people living in coastal areas, natural disasters are becoming more frequent as hurricanes and typhoons and the melting of ice caps all impact the ability to fish and maintain livelihoods, infrastructure, and food security.

Farmers are struggling to keep their animals healthy in drier conditions and the lack of water is affecting the quality of soil, drying it into dust, creating problems with growing crops. As the volume of resources and fertile lands continue to decrease, competition and conflict between farms in certain areas is starting to arise as they compete for access to clean water and arable land. It is predicted that global food yields could decline by as much as 30% by 2050 if farmers are not able to adapt to these environmental changes (Chandler, 2023). In some areas these environmental challenges are so extreme that farming is not an option anymore. According to Mark Chandler of Heifer International, extreme weather displaced more than 23 million people (about the population of New York) globally due to people having to search for new means of work. In the world’s most vulnerable nations, climate change is worsening conflicts and competition over natural resources. When violence erupts, it disrupts communities, forces farmers to leave their land, and raises the risk of unemployment.

Conflict – Agribusinesses and Land Grabbing

Conflict is one of the main contributors to preventing food accessibility. Places affected by conflict must deal with the displacement of populations, destruction of agricultural infrastructure, and disturbance of food chains. All factors are increasing the effects of food scarcity. It is becoming common for large companies to expand their factories or plants to mass produce their products. This removes farmers from the land, which was once theirs, having no choice but to pursue another measure of work. However, this is not the only type of conflict that is taking place. Areas where active violence and war action occur encompass the other side of how conflict forcefully changes people’s way of life. This is currently happening to the people who live in Ukraine, where people are having to evading their homes due to violence and worrying about their safety. Not only do these people struggle to afford food after being displaced, but they also have limited access to quality grocery stores due to moving to unfamiliar areas.

The understanding of large scale “agribusiness” can be described with the term known as “land grabbing.” This term means having the ability to obtain larger than normal amounts of land either by a person or company through any means necessary whether it is by using legal or illegal actions. This is often done through ownership, contracts, leases, or deliberate power to extract resources or agricultural uses among many others. Over the past decade, multinational corporations, foreign investors, and local governments have been progressively acquiring large areas of farmland for agribusiness (Honkaniemi, 2021). The media coverage of these companies performing large land grabs has declined even though the problem remains prevalent. Large acquisitions of farmland by these companies, like stated above, are aggressively causing issues of displacement for rural communities.

Land grabbing received a lot more attention from the media in the early 2000’s, having it been around 20 years later, the problem remains far from solved. Between the years of 2006 and 2016, 491 land grabs motivated by agriculture took place (Honkaniemi, 2021). This amounted to 30 million hectares of land in 78 countries (74131614.44 acres). A recent example that has been floating around is the aggressive events that have taken place in Kiryandongo, Uganda. This investigation was conducted by Grain, a small international non-profit organization that works to support small farmers and social movements. With backing from the Ugandan government, three international corporations have been involved in aggressive land acquisitions, forcing thousands of families from their homes (AFSA, GRAIN, 2020). The three companies that are land grabbing in Kiryandongo are Kiryandongo Sugar Limited, Great Season SMC Limited, and Agilis Partners. Kiryandongo Sugar is a Kenyan-based business group that own a variety of plantation, food, and timber companies. Over the past decade they have become one of the continent’s largest players in the production and import of sugar. Several of its sugar companies are in conflict due to the continued and resulting displacement of 5,000 individuals. There is not a lot of information on Great Season SMC Unlimited, the local people of Kiryandongo believe it is owned by Sudanese businessmen that are based in Dubai (AFSA, GRAIN, 2020). Agilis Partners, founded by twin brothers Phillip and Benjamin Prinz from the United States, began its operations in 2013 with the establishment of the Joseph Initiative, a maize trading company. This company sources maize from out grower farmers in the Masindi District, who had previously been engaged in contract farming for British American Tobacco.

Bending the rules and finding loopholes in certain laws that are already in place is a big reason why land grabbing is beneficial for companies due to the accessibility of being able to participate in the practice. Land grabbing occurs both legally and illegally under current laws in place. In fact, most land grabs are considered legal meaning they obey both federal and local laws (Fuller, 2020). These laws, however, do not protect against instances where local community access to lands is obstructed because of land grabs. This brings up the question of why governments are allowing this to happen, and it’s a simple answer, profit. Money has great influence in this practice, it is very common for governments to have a price point, that if met, companies are able to claim land from people who don’t technically have proper ownership of it. Most of the time, small farmers or indigenous communities lack documented ownership of land because it was passed down from generation to generation. If the acquisition of land were to be pursued legally by an individual with no documented title to the land, they wouldn’t get very far and most likely losing their land anyway.

Governments are often promised economic development by large scale operations who plan on converting lands they acquire into areas where they can practice biofuel production. Companies well versed in land grabbing understand how to use money and promises with governments to acquire land, but they are also not afraid to directly meet the individuals who have owned the land for generations. In many cases, private militias and armed forces have been used to intimidate landowners and forcefully remove them. Due to present factors that affect the economy, some farmers are forced to sell their land because of rising debts or failing crops and this is where companies are able to again take advantage of small farming operations. By offering low prices for land and binding farmers to deceptive contracts, over time they are able to push people out of ownership of their property.

Focusing back in on the people in Uganda, the local community of Kiryandongo farmed a variety of crops and raised many animals before their lands were taken. Their lands have been converted into diverse farmlands used for growing maize, coffee, sugarcane, and soya which are all highly profitable exports that are being shipped elsewhere (Honkaniemi, 2021). Interesting enough, one of these companies is producing cereal for the United Nations World Food Program even though the people of the local community are suffering from malnutrition and hunger. Since being displaced and having no other options in finding new means of making a living, many people of the local community have been forced to seek out jobs within the companies who were responsible for their displacement. Receiving below minimum wage and working in conditions that are not always regulated for proper safety measures, they are forced to keep quiet through violent actions taken by company security forces and Ugandan officials. Incidents like those in Kiryandongo have become increasingly common in recent decades, as multinational corporations, foreign investors, and local governments frequently prioritize profits over the well-being and rights of rural communities.

Land grabbing as a whole has significant effects on food accessibility. When large companies displace small-scale farmers and convert their land for large-scale agricultural production, local food availability declines, and displaced individuals are often forced into unstable job situations. This shift not only limits access to affordable, locally grown food but also disrupts traditional farming methods that many communities rely on for survival. As more land is dedicated to exporting crops like maize, coffee, and sugarcane, local populations are left with fewer resources to meet their own food needs, worsening food insecurity. Addressing this issue requires stronger regulations, improved land rights protections for vulnerable groups, and increased awareness of the lasting impact on food accessibility.

Farmlandgrab.org, Illustration, 2018

Conflict – War Activity

Shifting back over to another side of conflict affecting many people around the world is the effect of war on communities and all the implications that come with it. In violent conflicts, the goal of each party is essentially to eliminate the other side, or their enemies. In doing so, the creation of battlefields, war zones, and frontlines are almost inevitable despite the advancements of increasing accurate weapons and machines used in war such as drones. This is why violent interactions are usually followed by destruction of physical infrastructure which affects the vulnerability of individuals and leads to continuous problems with violence and hunger (Kemmerling, Schetter, Wirkus, 2022).

On average, Collier (1999) reports that during civil wars, a country’s gross domestic product (GDP) per capita decreases by approximately 2.2% per year. The agricultural sector experiences disproportionately higher levels of physical destruction compared to other industries, as conflicts primarily occur in rural areas where insurgents and rebel groups can easily establish hideouts and strongholds (Fearon and Laitin, 2003). Small-scale farming and animal breeding, which are essential for subsistence economies, are particularly vulnerable to the destructive impacts of war. The damage or contamination of agricultural land—through bombings, land mines, or chemical weapons—along with the destruction of critical infrastructure such as irrigation systems, roads, and bridges, not only results in significant losses in agricultural production but may also force farmers to abandon farming entirely. Additionally, limited access to seeds, fertilizers, credit, and capital, combined with market disruptions and the displacement or loss of people, further prevents farmers from cultivating their land (Baumann and Kuemmerle, 2016).

It is important to understand that countries affected by war take long periods of time to recover from all the damage that it experienced from war conflicting activities. The rehabilitation of war zones doesn’t just occur within a couple weeks, especially regarding food production and food supply, this can take decades (Kemmerling, Schetter, Wirkus, 2022). Post-conflict reconstruction is typically slow and expensive, involving tasks such as removing landmines, restoring infrastructure, and re-establishing governance. These efforts are often complicated by intense disputes over land and water ownership, as property rights frequently shift during wartime. As a result, food insecurity, especially among poorer communities, often continues well after active conflict has ended (Van Leeuwen & Van Der Haar, 2016). Conflict has both immediate and long-lasting effects on food security. When people are displaced by violence, agricultural production often collapses, infrastructure deteriorates, and supply chains at both local and regional levels are disrupted. This leads to rising food prices and limited access to essential resources. Displaced individuals, many of whom were once food producers like farmers and pastoralists, lose their livelihoods and often face serious food insecurity, particularly if they’re unable to resume agricultural work in their new environments.

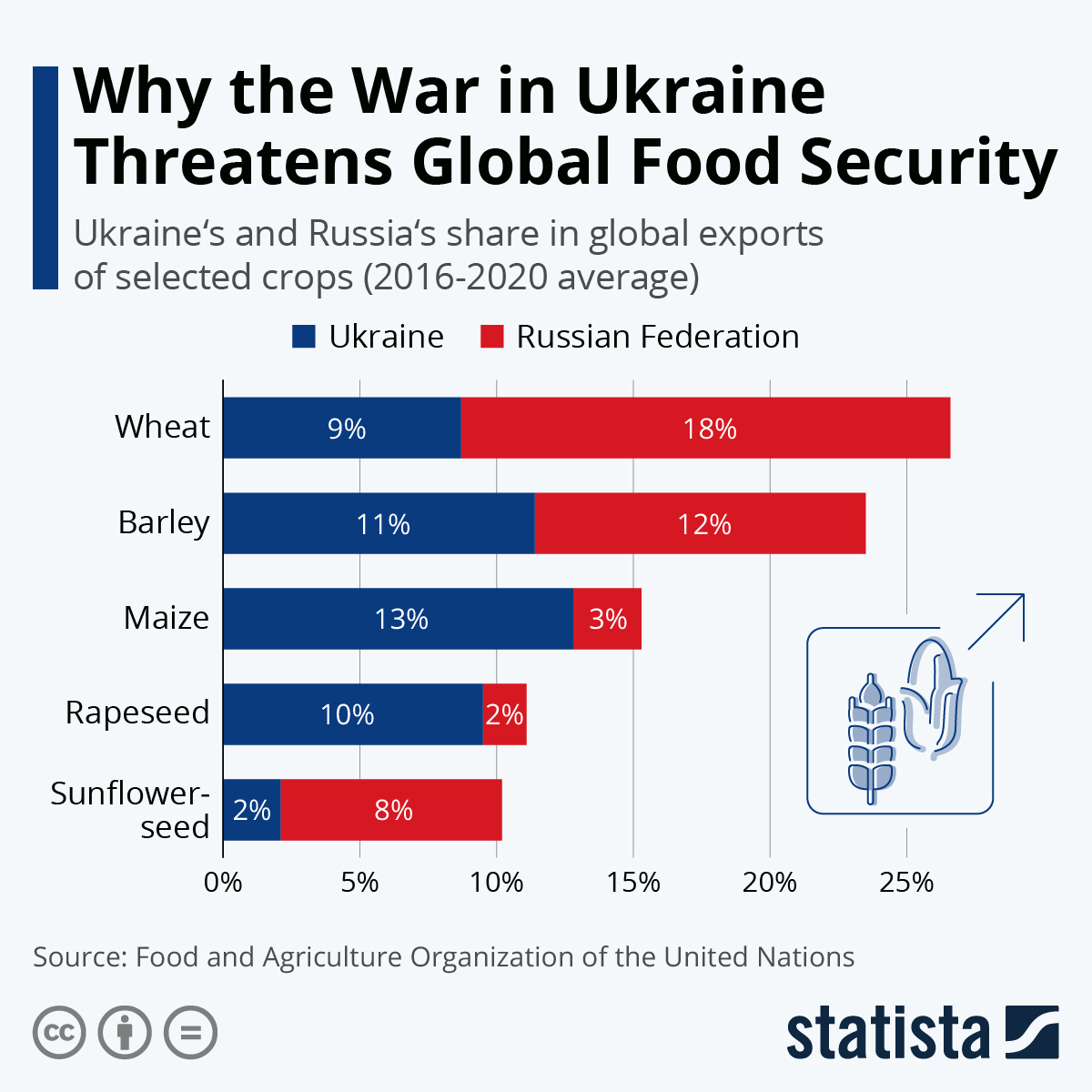

Like previously mentioned earlier, these outcomes and disadvantages that persist due to war conflicts is exactly what is occurring in Ukraine right now. The war in Ukraine, which began in February 2022, has significantly strained food security both within the country and around the world. This crisis is largely driven by rising food prices and major disruptions to global supply chains. As a key agricultural producer, Ukraine plays a critical role in global food markets, supplying about 20% of the world’s wheat exports, along with substantial portions of corn (10%) and sunflower (45%) production (Filho et al., 2023). Global food prices, which were already elevated prior to the conflict, have surged even further due to the war. The most heavily impacted commodities include wheat, maize, edible oils, and fertilizers. Several factors contribute to this trend, including reduced grain availability, rising energy and fertilizer costs, and major disruptions to trade caused by the closure of key ports.

The war has hindered Ukraine’s ability to transport commodities. Prior to the “Initiative on the Safe Transportation of Grain and Foodstuffs from Ukrainian ports” being signed, just about all of their grain exports went through the black sea which was not operational. The situation in Ukraine remained critical throughout 2023. Following the collapse of the Grain Deal, shelling directed at Ukrainian territory resulted in the destruction of 180,000 tonnes of grain and caused damage to 26 port infrastructure facilities and five civilian vessels, according to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine. Beyond immediate disruptions to food supply chains, the war is also expected to have long-term consequences for Ukraine’s agricultural production. The war is projected to significantly disrupt Ukraine’s agricultural production in the upcoming seasons. Planting periods for major crops including maize, barley, and sunflowers in the spring and winter wheat in the fall, are likely to be affected. Labor shortages, limited access to inputs such as fuel and fertilizers, destruction of farming equipment, and security concerns for growers are expected to have a substantial impact. Estimates suggest that Ukraine’s agricultural output could decline by 25 to 50 percent in the next season (Filho et al., 2023).

At the start of the crisis, food insecurity quickly became widespread across Ukraine, with a significant portion of the population struggling to access sufficient resources. The sharp decline in ships transporting agricultural goods led to major disruptions in food supply chains, driving prices even higher. In addition, the war caused widespread closures of Ukrainian ports and interrupted critical processes like oilseed crushing, further limiting food exports and intensifying global price spikes. The ripple effects of the conflict have contributed to record levels of food insecurity around the world. By mid-2022, millions more people faced acute food shortages or were at high risk, with particularly sharp increases across regions such as Asia and the Pacific, the Middle East, Africa, Eastern Europe, and Latin America. According to the FAO’s 2023 report, nearly 600 million people are projected to be chronically undernourished by 2030, highlighting the significant gap remaining before the Sustainable Development Goal of ending hunger can be achieved. This number is substantially higher than it would have been without the pandemic and the war in Ukraine, with the conflict alone adding an estimated 23 million more undernourished people (Filho et al., 2023). Building on this, the ongoing conflict in Ukraine has the potential to spark a global food crisis, as 36 of the 55 countries already experiencing food insecurity depend heavily on exports from Ukraine and Russia.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Graphic, 2022

What Can be Done?

It is no secret that there are many causes that contribute to issues with food accessibility and different parts of the world deal with these issues at more extreme levels than others. The war in Ukraine, along with other global issues, has seriously ramped up food insecurity like never before. With millions of people around the world struggling with hunger and unreliable food supplies, it’s super important to start talking about real solutions. We need a global effort that not only provides immediate help but also works on creating stronger, more sustainable food systems for the future.

According to the USDA, a significant portion of the food supply is wasted each year, with the United States alone discarding between 30 and 40% of its total food production. On a global scale, roughly 30% of food is lost or wasted, an amount that could feed up to 2 billion people. Food waste occurs at multiple points along the supply chain, from farms and factories to grocery stores and households. Whether it’s due to spoilage during transport, rejection for cosmetic imperfections, or disposal after passing sell-by dates, an overwhelming amount of food in the U.S. is ultimately discarded (Poverty USA, n.d.). One practical solution to reducing food waste is to enhance transparency and consistency in food labeling practices. Consumers are often confused by the differences between terms like “best-by,” “use-by,” and “sell-by,” which can result in perfectly safe food being thrown away prematurely. Implementing standardized date labeling could help reduce this confusion. In fact, the USDA notes that most foods remain safe to eat beyond these dates as long as there are no signs of spoilage and they have been stored properly.

Another systematic change that would be beneficial is for SNAP benefits to continue to be modernized. The supplemental nutrition assistance program has been helping millions of families around the country, but it has the potential to help many more around the world. SNAP benefits are currently based on the USDA’s “thrifty food plan” (TFP), which is one of four food plans USDA develops that estimates the cost of a healthy diet across various price points. However, the TFP is essentially outdated for several reasons including not reflecting current dietary guidelines and food prices and it doesn’t meet all the U.S.’s federal nutritional standards (Poverty USA, n.d.). Households in areas with high living costs often find themselves allocating a large portion of their income to essentials like housing, leaving limited funds for food. In many of these cases, government assistance programs such as SNAP fall short of meeting families’ nutritional needs. There is great potential for SNAP benefits to be a solution that will contribute to solving food insecurity, but it is need of systematic reconstruction and globalization.

Fairfaxcounty.gov, Illustration, 2023

On a larger scale, the impact of smallholder farms adapting to the current levels of climate change would be very beneficial. As mentioned before, implementing adaptation and mitigation strategies among smallholder farmers presents a significant challenge. These farms are often fragmented and operate on a small scale, with limited access to essential resources such as agricultural inputs, modern technologies, and financial support. There are small steps and practices that farmers at both small and large scales can take to resist disparities caused by climate change. Practices include improving animal and crop production, using farming land more efficiently, and reducing the loss and waste of crops during planting and harvesting.

Given these challenges, the effectiveness of adaptation strategies relies on aligning solutions with the unique environmental and agricultural contexts of different regions. Different countries have different priorities when it comes to adapting to climate change. These priorities usually depend on how much a country is exposed to climate-related risks and the types of farming systems used in those areas (Poverty USA, n.d.). For instance, drought-resistant seeds are more relevant in places like India or Mexico where droughts are common and crops are widely grown. In contrast, in Ethiopia’s drought-prone regions, people mostly rely on livestock instead of farming crops, so that kind of adaptation doesn’t make as much sense there. Ultimately, farmers who implement a combination of adaptive measures are likely to enhance their resilience to climate challenges.

While customized adaptation strategies help farmers tough out climate challenges, tackling food insecurity on a larger scale calls for community-driven efforts to ensure everyone has access to sufficient, nutritious food. Food insecurity affects every community, with varying degrees of severity, but no region remains untouched. Engaging in efforts to reduce hunger offers a meaningful way to strengthen local communities and foster resilience. Several accessible approaches exist to contribute, regardless of one’s available resources or time. Volunteering with food banks or community cooperatives provides critical support, delivering food to those in need while fostering local connections and mutual aid. Additionally, contacting local or national representatives to advocate for systemic solutions, such as expanding nutrition assistance programs or protecting smallholder land rights, amplifies community concerns. Donating money or food items to organizations addressing hunger also makes a significant impact, as even small contributions can help meet urgent needs. Globally, initiatives like the World Food Programme’s ShareTheMeal app enable individuals to fund meals for vulnerable populations, demonstrating how collective micro-actions can scale impact (World Food Program USA, 2025). By combining efforts with global cooperation and policy reform, we can envision a future where food accessibility is no longer a barrier, ensuring equitable access to nutrition for all.

Works Cited

Ambassadors, Medical. “Nourishing Hope: Tackling the Global Challenge of Food Scarcity.” Medical Ambassadors International, Medical Ambassadors https://www.medicalambassadors.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/medical-ambassadors-international-logo-300×138.png, 18 Jan. 2024, www.medicalambassadors.org/title-nourishing-hope-tackling-the-global-challenge-of-food-scarcity/?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQiAwOe8BhCCARIsAGKeD57cC6cOEU6p_M7Z77MWVd7XM4q5hupj9O1SvJX41u1f-PRdz_gfJQ8aAphYEALw_wcB.

Baumann, Matthias, and Tobias Kuemmerle. “The Impacts of Warfare and Armed Conflict on Land Systems.” Taylor and Francis Online, 8 Oct. 2016, www.researchgate.net/publication/232173635_httpwwwtandfonlinecomdoiabs101080009140390909763.

Chandler, Mark. “How Does Climate Change Affect Agriculture? | Heifer International.” Heifer International, Mar. 2023, www.heifer.org/blog/how-climate-change-affects-agriculture.html.

Collier, P. “On the Economic Consequences of Civil War | Oxford Economic Papers | Oxford Academic.” Oxford Economic Papers, Jan. 1999, academic.oup.com/oep/article-abstract/51/1/168/2361710?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

Fearon, James D., and David D. Laitin. “Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War: American Political Science Review.” Cambridge Core, Cambridge University Press, 12 Mar. 2003, www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-political-science-review/article/ethnicity-insurgency-and-civil-war/B1D5D0E7C782483C5D7E102A61AD6605.

Fuller, Hannah. “Deep Dive: Land Grabs.” Grounded Grub, Grounded Grub, 8 Dec. 2020, groundedgrub.com/articles/deep-dive-land-grabs.

GRAIN, et al. “Land Grabs at Gunpoint: Thousands of Families Are Being Violently Evicted from Their Farms to Make Way for Foreign-Owned Plantations in Kiryandongo, Uganda.” GRAIN, 25 Aug. 2020, grain.org/en/article/6518-land-grabs-at-gunpoint-thousands-of-families-are-being-violently-evicted-from-their-farms-to-make-way-for-foreign-owned-plantations-in-kiryandongo-uganda.

Honkaniemi, Sanna. “Global Agribusiness Continues to Displace Rural Communities.” FUF.Se, 3 May 2021, fuf.se/magasin/global-agribusiness-continues-to-displace-rural-communities/.

Kemmerling, Birgit, et al. “The Logics of War and Food (in)Security.” ScienceDirect, Elsevier, 4 Apr. 2022, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211912422000256.

Leal Filho, Walter, et al. “How the War in Ukraine Affects Food Security.” PubMed Central, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 31 Oct. 2023, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10648107/#:~:text=In%20May%202022%2C%20it%20was,on%20food%20prices%20%5B12%5D.

Leeuwen, Mathijs Van, and Gemma Van Der Haar. “Theorizing the Land–Violent Conflict Nexus.” Science Direct, Pergamon, Feb. 2016, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X15002338.

Ploeg, Michele Ver. “Access to Affordable, Nutritious Food Is Limited in ‘Food Deserts.’” Access to Affordable, Nutritious Food Is Limited in “Food Deserts” | Economic Research Service, 1 Mar. 2010, www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2010/march/access-to-affordable-nutritious-food-is-limited-in-food-deserts.

Poverty USA. “What Causes Food Insecurity and What Are Solutions to It?” Poverty USA, www.povertyusa.org/stories/what-causes-food-insecurity-and-what-are-solutions-it. Accessed 18 Apr. 2025.

US Department of Agriculture. “Food Waste Faqs.” Home, www.usda.gov/about-food/food-safety/food-loss-and-waste/food-waste-faqs. Accessed 18 Apr. 2025.

World Food Program USA. “Sharethemeal.” World Food Program USA, 1 Apr. 2025, www.wfpusa.org/sharethemeal/#:~:text=ShareTheMeal%20is%20the%20award%2Dwinning,a%20tap%20on%20their%20smartphone.

Zenk, Shannon N, et al. “Food Accessibility, Insecurity and Health Outcomes.” National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2022, www.nimhd.nih.gov/resources/understanding-health-disparities/food-accessibility-insecurity-and-health-outcomes.html.

Created by Cayden Knipper