30 US Water Quality Issues and Regulations

The Impact of PFAS Contamination

In 2019, residents of Oscoda, Michigan, were shocked to learn that their drinking water had been contaminated with dangerous levels of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). The contamination stemmed from the nearby Wurtsmith Air Force Base, where firefighting foams containing PFAS had been used extensively for decades. Families who had lived in the area for generations began to see disturbing patterns—unexplained illnesses, rising cancer rates, and developmental delays in children. For many, the water they had trusted for cooking, drinking, and bathing was now a source of fear. Local activists fought tirelessly for clean-up efforts, but the response from government agencies was slow, and the health effects were already taking their toll (Dwyer and Herndon, 2024). (EF)

This is not an isolated case. Across the United States, from military bases to industrial sites, communities are facing similar struggles. In Parkersburg, West Virginia, the DuPont chemical company was sued for contaminating the drinking water with PFOA, a specific type of PFAS, leading to an increase in cancer cases and other severe health conditions. The landmark case, depicted in the film Dark Waters, brought national attention to the dangers of these chemicals and the challenges of holding corporations accountable. People who have unknowingly consumed contaminated water for years are now suffering from serious health conditions, and the full extent of PFAS exposure remains uncertain. (EF)

What are PFAS?

PFAS are a group of manufactured chemicals called per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. There are thousands of different PFAS, and some are used more frequently than others. These synthetic chemicals have been used in everyday products since the 1940’s-50’s including nonstick cookware, stain-resistant clothing materials, and highly effective firefighting foam. These chemicals are often referred to as “forever chemicals” because they take a very long time to break down in our environment. PFAS molecules contain a chain of linked carbon and fluorine atoms (polyfluoro-), and the bond between these atoms is very strong. Therefore, there aren’t many forces present in our natural environment that can degrade these molecules. (EF)

The PFAS that are studied most frequently include perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS). These specific chemicals have been phased out of use in the United States, but they may still be produced in other countries. While the removal of PFAS from US production may seem like a positive first step, we often develop new PFAS with similar properties to replace the restricted substances. This is one of the reasons why PFAS research is still developing- new experiments and methods of study are needed whenever a new variety of PFAS makes its way into production (US EPA, 2023). (EF)

How do they impact people? What are the health effects?

The health effects of PFAS exposure are still being investigated, but there have been some clear connections draw between increases in exposure to PFAS and a variety of negative health effects in humans. The risk of health effects from PFAS depends on multiple factors including dose, exposure frequency, exposure route, and exposure duration. Additionally, individuals may experience different health effects depending on personal health factors such as sensitivity and disease burden. Environmental justice- related issues also play a role in PFAS exposure. An individual’s access to safe drinking water and quality healthcare can be an external determinant of health and play a role in PFAS- related health issues. (EF)

Here is a list of some associations we see as a result of increased PFAS exposure (CDC, 2024):

- Decreases in birth weight

- Lower antibody responses to specific vaccines

- Increased cholesterol levels and/ or risk of obesity

- Kidney and testicular cancer

- Developmental delays in children

- Reproductive effects (decreased fertility, increased high blood pressure in pregnant women)

- Interference with the body’s natural hormones

How are people exposed to PFAS? How can we decrease these exposures?

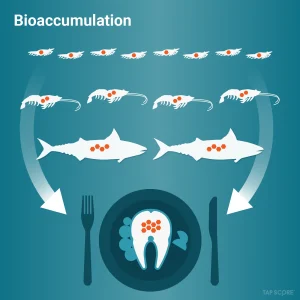

Because PFAS are used in a variety of industries, our exposure to them is very widespread and variable across different locations and lifestyles. Typically, humans are exposed to PFAS through contaminated water or food, by using products made with PFAS, or by breathing air contaminated with PFAS. These forever chemicals leach into our waterways from multiple sources, contaminating everything downstream and making it difficult to pinpoint any particular source. As previously discussed, these molecules take a long time to break down. This means that repeated exposures to PFAS simply increase the amount we have in our bodies. This process is called bioaccumulation, and it happens all over our environment with many different substances. One way PFAS can bioaccumulate is through food chains. When organisms lower in the food chain become contaminated with PFAS, the larger organisms that eat them are also contaminated. As this process continues, the amount of PFAS in each trophic level continues to increase. This makes it difficult to track the levels of PFAS contamination- I may only eat one fish that was contaminated with PFAS, but the amount that had bioaccumulated in that organism represents the amount of PFAS present in all lower levels of the food chain. (EF)

(Stovne, 2018)

Awareness of PFAS is one of the best ways to reduce exposures, and you can take steps to reduce the amount of these chemicals you come in contact with. One of the simplest examples of how we can make small changes is by not using non-stick cookware. Teflon is a notorious non-stick coating that is made with PFAS and is linked to several health risks. By swapping these pots, pans, and baking sheets for ones made of stainless steel or cast iron, you can easily reduce the amount of PFAS that make their way into your food and water. (EF)

How can we remedy this problem?

The Safe Drinking Water Act (1974) is the main federal law that protects public drinking water nationwide. It’s under this law that the EPA has the authority to set enforceable standards and regulations for specific substances in our water. They can also require testing of all public water supplies. It should be noted that the SDWA does not apply to private domestic wells or to other private or public water not being used for drinking (Interstate Technology Regulatory Council, 2016). (EF)

Regulating PFAS in the United States requires the collaboration of a number of federal and state governing agencies and policy initiatives. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are both key players in this arena. Beginning in 2021, the EPA released the first PFAS Strategic Roadmap, an annual progress report detailing the research, policy actions, and reporting methods regarding PFAS that the organization had worked on in the past year. In April 2024, the EPA issued the first-ever, “national, legally enforceable drinking water standard to protect communities from exposure to harmful PFAS, (CITE EPA)”. This rule dictates specific maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) for six different PFAS. These values range from 4 to 10 parts per trillion. The EPA estimates that this standard will prevent exposure to PFAS in drinking water for roughly 100 million people. Large-scale policy actions like this require lots of work and, subsequently, investment. After all, in order for public water utilities to meet these standards, they must monitor PFAS levels for three years. If this initial monitoring reveals PFAS in concentrations above the maximum contaminant levels, water utilities have until 2029 to implement appropriate solution. Beginning in 2027, public water systems must also provide information to the public about the levels of PFAS in their water. All of this additional work to regulate PFAS in drinking water will require more people and more money, so the EPA also allocated $1 billion from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. This is only one example of how complicated it can be to enforce national-level environmental policies. However, large-scale efforts yield large-scale results (“Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS),” 2024). (EF)

Lead Contamination and Water Infrastructure in the US

The integrity of water infrastructure in the US is fundamental to public health, ensuring the delivery of safe drinking water. Much of the nation’s water infrastructure is aging, leading to significant challenges. Included among these is concerning issues is lead contamination. Many US water systems are over 100 years old with pipes and treatment facilities reaching the end of their intended lifespans. This deterioration results in roughly 240,000 water main breaks each year, disrupting communities and introducing health risks. A critical concern is the presence of lead service lines in these aging systems. It is estimated that millions of households in the US receive water through lead-containing pipes, exposing approximately 22 million people to potential lead contamination (Fawkes and Sansom, 2021). (EF)

Lead is a toxic metal with no safe exposure level. In children, it can cause neurological damage, developmental delays, and behavioral issues. Adults may experience hypertension, kidney dysfunction, and reproductive problems. Notably, lead exposure accounts for roughly 412,000 deaths annually in the US, highlighting its severe public health implications (US EPA, 2018). The Flint, Michigan crisis showed us all the dangers of lead contamination from aging infrastructure. A switch in water source without proper corrosion control measures led to widespread lead exposure, affecting thousands of people and bringing national attention to the issue. In response, regulatory measures have been implemented. The US EPA set the maximum contaminant level goal for lead in drinking water at zero, indicating its high toxicity. Additionally, the Lead and Copper Rule (1991) mandates water systems to monitor and control lead levels with recent revisions aiming to strengthen protections and enforcement (McBride and Berman, 2023). Addressing the challenges posed by aging water infrastructure and lead contamination requires comprehensive strategies, including investment in infrastructure, policy actions and reforms, and increased public awareness. (EF)

US Water Infrastructure

The United States’ water infrastructure, including over 2.2 million miles of pipelines, is increasingly strained by environmental stressors and systemic disparities. Climate change poses significant challenges to water utilities. Rising temperatures and prolonged droughts decrease water recharge, affecting both water supply and quality. These conditions negatively affect utilities’ capacity to serve customers effectively and collect revenue. Additionally, extreme weather events, such as hurricanes and floods, can overwhelm aging infrastructure, leading to service disruptions and contamination risks. For example, excessive rainfall can cause sewer systems to overflow, discharging untreated wastewater into natural water bodies. The EPA emphasizes the need for utilities to adapt to changing environmental conditions (US EPA, ORD, 2019). (EF)

Access to reliable water services is not evenly distributed across the country. Approximately 13% of the US population is not served by public water systems, relying instead on domestic wells that may lack proper maintenance and monitoring (Allaire, et al., 2024). Racial and economic factors further exacerbate these disparities. Marginalized communities including Black, Indigenous, communities of color, and low-income populations often face structural inequities in water affordability and quality. These groups are more likely to experience service shut-offs, contamination issues, and less-than-adequate infrastructure investment (VanDerslice, 2011). Financial constraints also play a role in perpetuating water access disparities. The EPA estimates that 12.1- 19.2 million households lack access to affordable water services with annual unaffordable bills totaling between $5.1 billion and $8.8 billion. Addressing these challenges requires targeted investments and community engagement to ensure equitable access to safe and reliable water services across the country. (EF)

Lead Contamination and Public Health

Lead contamination in drinking water remains a major public health crisis in the United States, directly linked to aging water infrastructure and inadequate regulatory enforcement. Although lead is not naturally present in water, it can leach from lead pipes, solder, and plumbing fixtures as water flows through outdated systems. The EPA estimates that between 6 and 10 million U.S. households still receive water through lead service lines (US EPA, 2018). (EF)

Lead exposure, particularly through contaminated water, can lead to severe health consequences. In children, it causes irreversible brain damage, developmental delays, and learning disabilities. In adults, it increases the risk of high blood pressure, kidney damage, and cardiovascular diseases. These health risks are heightened in communities with aging infrastructure, where corrosion control measures are often insufficient, allowing lead to seep into the water supply. Addressing lead contamination requires not only replacing aging pipes but also enforcing strict water quality regulations and implementing corrosion control measures to protect public health. (EF)

Climate Change and Water Quality in the US

Climate change is reshaping the natural and built environments across the United States, with water systems among the most vulnerable to its impacts. Rising temperatures, shifting precipitation patterns, and more frequent extreme weather events are placing increasing stress on drinking water sources, treatment infrastructure, and public health safeguards. As climate change accelerates, the risks to water quality are multiplying—creating new challenges and compounding long-standing issues like microbial contamination, toxic algal blooms, and pollutant runoff. (EF)

Clean, safe drinking water is a fundamental public health necessity. Yet, in communities across the country, especially those already facing aging infrastructure or underinvestment, climate-related disruptions are threatening the reliability and safety of water supplies. In both rural areas reliant on groundwater and urban centers with combined sewer systems, climate change is making it more difficult to manage contamination risks and ensure equitable access to safe water. (EF)

Climate change is affecting water quality in the U.S. in ways that demand urgent attention, particularly where environmental stressors intersect with infrastructure vulnerabilities and public health. Flooding, drought, and rising water temperatures all contribute to contamination risks—from microbial outbreaks to harmful algal blooms and chemical pollutants. These challenges are especially acute in communities with outdated water systems or limited resources, where the effects of climate change are felt most severely. Addressing these threats requires a coordinated response that includes both short-term mitigation and long-term planning. Strengthening regulatory frameworks, investing in resilient infrastructure, and prioritizing equity in access to clean water are essential steps to protect both environmental and human health in an era of accelerating climate instability. (EF)

Environmental Stressors

Climate change is intensifying environmental stressors that directly impact water quality across the United States. Three major factors—flooding, drought, and rising water temperatures—are increasingly undermining the safety and reliability of drinking water supplies. (EF)

- Flooding and Stormwater Runoff

More frequent and intense storms are overwhelming aging stormwater systems, leading to increased runoff that carries pollutants like sediments, nutrients, and pathogens into water bodies. This runoff can degrade source water quality and pose significant health risks. In urban areas, combined sewer overflows during heavy rainfall can discharge untreated sewage directly into waterways, exacerbating contamination issues (“Storms and Flooding”, 2025).

- Drought and Water Scarcity

Prolonged droughts, particularly in the western U.S., are reducing surface water availability and increasing reliance on groundwater sources, which may be more susceptible to contamination. Lower water levels can concentrate pollutants, making treatment more challenging. Additionally, drought conditions can lead to higher water temperatures, further impacting water quality (“Drought and Climate Change, 2025).

- Rising Water Temperatures and Algal Blooms

Elevated water temperatures, combined with nutrient-rich runoff, create ideal conditions for harmful algal blooms (HABs). These blooms can produce toxins that contaminate drinking water sources and pose health risks to humans and animals. The frequency and intensity of HABs are increasing, affecting both freshwater and marine ecosystems (US EPA, 2016). (EF)

Climate change is intensifying water quality challenges that pose direct threats to public health. As environmental stressors increase in frequency and severity, so too does the risk of exposure to things like waterborne pathogens, toxicants, and contaminants. The health effects from these exposures are felt most acutely in communities with aging infrastructure or limited access to safe water treatment technologies. Flooding and stormwater runoff can overwhelm municipal water systems, causing combined sewer overflows and introducing dangerous pathogens like E. coli, Cryptosporidium, and Giardia into drinking water supplies. These microorganisms cause gastrointestinal illnesses, and the US EPA has found that these symptoms are more prevalent after extreme weather events (2016). Meanwhile, harmful algal blooms (HABs), driven by warmer water temperatures and nutrient-rich runoff, produce toxins that can lead to skin irritation, liver damage, and neurological effects (CDC, 2024). (EF)

Drought-related water scarcity can increase concentrations of contaminants such as nitrates and heavy metals in source water, exacerbating health risks—especially for populations relying on unregulated private wells. Warmer water temperatures also create favorable conditions for Legionella bacteria, which can proliferate in building plumbing systems and cause Legionnaires’ disease, a severe form of pneumonia. Low-income, rural communities often face higher exposure to these hazards due to systemic inequities in infrastructure investment and access to safe water systems (US EPA, 2016). As climate threats grow, ensuring equitable access to safe drinking water must become a public health priority. (EF)

Policy/ Regulatory Landscape

The United States’ approach to water quality and climate resilience is shaped by a complex interplay of federal, state, and local policies. At the federal level, the Environmental Protection Agency enforces key legislation such as the Clean Water Act, which regulates pollutant discharges into U.S. waters and sets water quality standards. However, these frameworks are increasingly challenged by the multifaceted impacts of climate change, necessitating more adaptive and comprehensive strategies. In response to these challenges, significant investments have been made to bolster water infrastructure and resilience. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law allocates over $50 billion to the EPA for improvements in drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater infrastructure—the largest federal investment in water infrastructure to date. This includes $15 billion dedicated to replacing lead service lines and $12 billion aimed at ensuring clean water for communities (EPA, 2021). (EF)

Despite these advancements, fluctuating policy shifts have introduced uncertainties. Efforts to roll back environmental regulations, including those related to coal ash waste management, have raised concerns about potential risks to groundwater and public health. Additionally, the suspension of grants under climate and infrastructure initiatives has been met with legal challenges, emphasizing the tension between executive actions and legislatively approved programs. At the state level, initiatives vary widely. Some states have developed comprehensive climate resilience plans, while others lack formal strategies, highlighting disparities in preparedness and resource allocation. Collaborative efforts, such as the Water Equity and Climate Resilience Caucus, aim to address these gaps by promoting policies that ensure equitable access to safe and affordable water, particularly for marginalized communities (“State Action on Resilience”). (EF)

Moving forward, it’s clear that the U.S. needs a more cohesive and equitable policy approach that fully integrates climate adaptation into water quality management. While current frameworks like the Clean Water Act and recent infrastructure investments are a good start, they often don’t go far enough to address the complex, climate-driven threats facing water systems today. Updating outdated water quality standards, increasing long-term funding, and expanding support for small or under-resourced utilities will be critical. It’s also important to encourage collaboration between federal, state, and local governments, especially in ways that prioritize historically marginalized communities. Ensuring everyone has access to safe, clean, and reliable water (regardless of geography or income) should be at the center of future U.S. public health and climate policy. (EF)