Burstein, Rajec & Sawicki, One Day on Designs

Design patents, which have existed since 1842, are available for “any new, original and ornamental design for an article of manufacture.” 35 U.S.C. § 171. Unlike utility patents, which protect how things work, design patents protect how things look.

The statutory subject matter provision for design patents is 35 U.S.C. § 171. In re Finch, 535 F.2d 70, 71–72 (C.C.P.A. 1976). Section 171(a) provides: “Whoever invents any new, original and ornamental design for an article of manufacture may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.” Therefore, “design patents are granted only for a design applied to an article of manufacture, and not a design per se . . . .” Curver Luxembourg, SARL v. Home Expressions Inc., 938 F.3d 1334, 1340 (Fed. Cir. 2019).

What types of designs might be applied to an article of manufacture? There are three longstanding types of patentable designs:

(1) A design for “surface ornamentation applied to an article”;

(2) A design for “the configuration or shape of an article”; or

(3) A design for the combination of both.

See U.S. Dep’t of Commerce, Patent & Trademark Office, Manual of Patent Examining Procedure § 1504.01 (9th ed. Jan. 2018) (“MPEP”). Today, applicants can obtain design patents for any of these types of designs, or any part (or parts) thereof. See In re Zahn, 617 F.2d 261 (C.C.P.A. 1980). The USPTO also allows applicants to claim designs that “encompass multiple articles or multiple parts within that article.” MPEP § 1504.01(b).

Section 171(b) states that “[t]he provisions of this title relating to patents for inventions shall apply to patents for designs, except as otherwise provided.” So what is “otherwise provided”? Sections 171-173 provide specific rules that apply only to design patents—specifically, § 172 provides only six months priority for international applications and § 173 sets the term of a design patent as “15 years from the date of grant.” Section 289 provides a special remedy that is only available for certain acts of design patent infringement. Otherwise, the statutory provisions we’ve studied in connection with utility patents also apply to design patents. So, for example, a patentable design must be novel and nonobvious. 35 U.S.C. §§ 102, 103. And a design patent must satisfy the requirements of § 112. However, the application of these sections and the tests used to analyze a design’s compliance with them are quite different. This sometimes strikes those who’ve studied only utility patents as odd or even troubling. But design patents cover fundamentally different types of inventions and use an entirely different claiming system; under these circumstances, it would be odd if the statutory requirements weren’t applied differently. Principles or practices developed with only utility patents in mind may or may not make sense for design patents and there is no reason why such principles or practices necessarily need to be applied to designs.

Like other patents, design patents are granted by the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office (USPTO) following substantive examination. Who examines design patent claims? Design patent examiners are not drawn from the general USPTO examiner corps. Instead, the USPTO hires people with backgrounds in design—people who majored (or have the equivalent experience) in fields like industrial design, architecture, graphic design, and fine arts—as design patent examiners. But you still have to have a technical background (i.e., be a member of the “patent bar”) to prosecute design patents for other people or to be lead counsel in a design patent proceeding before the PTAB. Does that make sense? For one argument for change, see Christopher Buccafusco & Jeanne C. Curtis, The Design Patent Bar: An Occupational Licensing Failure, 37 Cardozo Arts & Ent. L.J. 263 (2019).

A. Scope

Before diving into the design patent validity doctrines, it’s important to understand the scope of a design patent. So we’ll start with how designs are claimed and then look at the test for design patent infringement.

1. Claiming

A design patent can only have one claim and that “claim shall be in formal terms to the ornamental design for the article (specifying name) as shown, or as shown and described.” 37 C.F.R. § 1.153(a). How is a design “shown and described”? The applicant must submit drawings or photographs, including “a sufficient number of views to constitute a complete disclosure of the appearance of the design.” 37 C.F.R. § 1.152. See also MPEP § 1503.02 (noting that photographs are also allowed). Color can also be claimed as part of a design, either by using color drawings or photographs or by using certain color shading conventions. Id.

For line drawings, anything shown in full lines is part of the claimed design. Applicants are also allowed to use broken lines in their design patent drawings:

The two most common uses of broken lines are to disclose the environment related to the claimed design and to define the bounds of the claim. Structure that is not part of the claimed design, but is considered necessary to show the environment in which the design is associated, may be represented in the drawing by broken lines. This includes any portion of an article in which the design is embodied, or applied to, that is not considered part of the claimed design. See In re Zahn, 617 F.2d 261 (CCPA 1980).

MPEP § 1503.02. (Note that the rules for broken line use have changed over time; don’t assume that broken lines in older design patents mean the same things they mean today.) An applicant might use broken lines to show how a claimed design might look in use, as in this drawing from a design patent that claims a design for a “Litter Box”:

U.S. Patent D816,281, fig. 1 (issued Apr . 24 , 2018). The cat is shown in broken lines and, therefore, is not a part of the claimed design. (If you look closely, you can see some other details of the litter box are also disclaimed.)

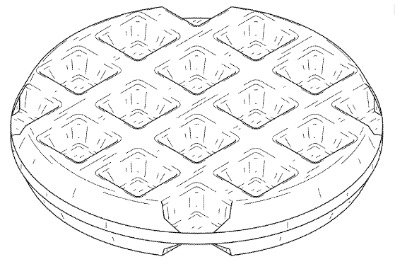

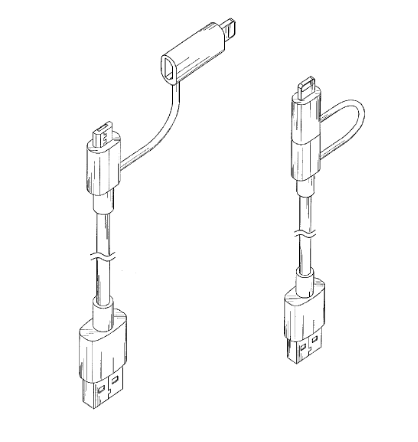

Broken lines can also be used to disclaim parts of an article’s shape or surface ornamentation. Consider, for example, this illustration from a design patent that claims a design for a “Pressed Shredded Potato Product”:

U.S. Patent No. D857,332, fig. 7 (issued Aug. 27 , 2019). The entire shape is shown in solid lines; therefore, the claim covers the entire shape. Compare that drawing to this one, from a design patent that was issued to the same patentee:

U.S. Patent D884,309 fig. 7 (issued May 19 , 2020). Why would an applicant want to disclaim part of a design? They do it to increase the scope of the design patent. As we’ll see below, a design patent is infringed when an accused product looks the same as the claimed design. If the claim only covers part of an article’s shape or surface ornamentation, then only the corresponding part of the accused product has to look the same. So this claim could be infringed by a pressed, shredded potato product that was round or square or any shape—as long as the dimple pattern (the part shown in solid lines) looks the same.

Broken lines can also be used to show unclaimed boundaries. In this case, “[i]t would be understood that the claimed design extends to the boundary but does not include the boundary.” MPEP § 1503.02. These boundary lines are often (though not always) depicted using dot-dash lines, while environmental and disclaimer lines are often depicted using plain dashed lines. Here is an example of a drawing, from a design patent that claims a design for “Footwear,” that uses both dashed disclaimer lines and dot-dash boundary lines:

U.S. Patent D787,798, fig. 1 (issued May 30, 2017). Why would someone want to draft a claim like this? Is it a “design for an article of manufacture”? See 35 U.S.C. § 171(a).

2. Infringement

It is an infringement to make, use, sell, offer to sell, or import a patented design (or to do any of the other things specified in 35 U.S.C. § 271). But how do we know if someone has made, used, or sold a patented design? The rules that have been developed to evaluate utility patent infringement don’t work for design patents because the claims and the inventions are so different. Indeed, ever since the Supreme Court’s first design patent case, Gorham v. White, courts have recognized that different infringement rules are needed.

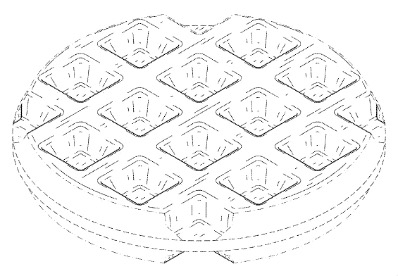

Gorham Co. v. White, involved U.S. Patent D1,440, issued in 1861 for a design for a “Fork and Spoon Handle.” Here is a representative drawing from that patent:

The lower court held that:

A patent for a design, like a patent for an improvement in machinery, must be for the means of producing a certain result or appearance, and not for the result or appearance itself. The plaintiffs’ patent is for their described means of producing a certain appearance in the completed handle. Even if the same appearance is produced by another design, if the means used in such other design to produce the appearance are substantially different from the means used in the prior patented design to produce such appearance, the later design is not an infringement of the patented one.

10 F. Cas. 827, 830 (C.C.S.D.N.Y. 1870). The lower court also held that infringement was to be determined from the point of view of an expert (“a person in the trade”), not from the perspective of “an ordinary purchaser.” Id. The patent owner appealed to the Supreme Court (which at that time, heard direct appeals in patent cases). As you read the excerpt below, pay close attention to how the Court answers the following questions: (1) What is the test for identity (infringement) of a design? and (2) From whose perspective should infringement be evaluated?

Gorham Co. v. White

81 U.S. 511 (1871)

Mr. Justice STRONG delivered the opinion of the court.

The sole question is one of fact. Has there been an infringement? Are the designs used by the defendant substantially the same as that owned by the complainants? To answer these questions correctly, it is indispensable to understand what constitutes identity of design, and what amounts to infringement?

The acts of Congress which authorize the grant of patents for designs were plainly intended to give encouragement to the decorative arts. They contemplate not so much utility as appearance, and that, not an abstract impression, or picture, but an aspect given to those objects mentioned in the acts. . . . The law manifestly contemplates that giving certain new and original appearances to a manufactured article may enhance its salable value, may enlarge the demand for it, and may be a meritorious service to the public. It therefore proposes to secure for a limited time to the ingenious producer of those appearances the advantages flowing from them. . . . The appearance may be the result of peculiarity of configuration, or of ornament alone, or of both conjointly, but, in whatever way produced, it is the new thing, or product, which the patent law regards. To speak of the invention as a combination or process, or to treat it as such, is to overlook its peculiarities. As the acts of Congress embrace only designs applied, or to be applied, they must refer to finished products of invention rather than to the process of finishing them, or to the agencies by which they are developed. . . .

We are now prepared to inquire what is the true test of identity of design. Plainly, it must be sameness of appearance . . . .

If, then, identity of appearance, or sameness of effect upon the eye, is the main test of substantial identity of design, the only remaining question upon this part of the case is, whether it is essential that the appearance should be the same to the eye of an expert. The court below . . . . thought there could be no infringement unless there was ‘substantial identity’ ‘in view of the observation of a person versed in designs in the particular trade in question—of a person engaged in the manufacture or sale of articles containing such designs—of a person accustomed to compare such designs one with another, and who sees and examines the articles containing them side by side.’ There must, he thought, be a comparison of the features which make up the two designs. With this we cannot concur. Such a test would destroy all the protection which the act of Congress intended to give. There never could be piracy of a patented design, for human ingenuity has never yet produced a design, in all its details, exactly like another, so like, that an expert could not distinguish them. No counterfeit bank note is so identical in appearance with the true that an experienced artist cannot discern a difference. . . . Experts, therefore, are not the persons to be deceived. Much less than that which would be substantial identity in their eyes would be undistinguishable in the eyes of men generally, of observers of ordinary acuteness, bringing to the examination of the article upon which the design has been placed that degree of observation which men of ordinary intelligence give. . . . The purpose of the law must be effected if possible; but, plainly, it cannot be if, while the general appearance of the design is preserved, minor differences of detail in the manner in which the appearance is produced, observable by experts, but not noticed by ordinary observers, by those who buy and use, are sufficient to relieve an imitating design from condemnation as an infringement.

We hold, therefore, that if, in the eye of an ordinary observer, giving such attention as a purchaser usually gives, two designs are substantially the same, if the resemblance is such as to deceive such an observer, inducing him to purchase one supposing it to be the other, the first one patented is infringed by the other. . . .

Context & Application

1. What does Gorham tell us about the purpose or purposes of design patent law? Do the goals identified by the Supreme Court seem like good goals for the system?

2. The most-quoted line from Gorham—“We hold, therefore, that if, in the eye of an ordinary observer, giving such attention as a purchaser usually gives, two designs are substantially the same, if the resemblance is such as to deceive such an observer, inducing him to purchase one supposing it to be the other, the first one patented is infringed by the other”—may strike contemporary readers as setting forth a trademark-like “likelihood of confusion” test. But that is not how the test was originally understood nor how it is understood today. Unette Corp. v. Unit Pack Co., 785 F.2d 1026, 1027 (Fed. Cir. 1986) (answering the question of “whether ‘likelihood of confusion’ is a factor to be determined under the Gorham test for infringement of a design patent” in the negative). See also Braun Inc. v. Dynamics Corp. of Am., 975 F.2d 815, 820 (Fed. Cir. 1992) (“Design patent infringement does not concern itself with the broad issue of consumer behavior in the marketplace.”). Read in the context of the case as a whole, Gorham sets forth a test of visual similarity. That most-quoted line tells us how similar the designs must be—so similar that an ordinary observer would mistake one for the other. See, e.g., Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. v. Hercules Tire & Rubber Co., 162 F.3d 1113, 1118 (Fed. Cir. 1998) (“Infringement of a design patent requires that the designs have the same general visual appearance, such that it is likely that the purchaser would be deceived into confusing the design of the accused article with the patented design.”) (emphasis added); Hector T. Fenton, The Law of Patents for Designs 129 (1889) (“The general rule for the determination of the question of infringement of design patents was enunciated by the Supreme Court, in Gorham v. White, to be similarity of general appearance to the eye of average observers.”) (emphasis added).

3. In Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc., the en banc Federal Circuit stated that:

In some instances, the claimed design and the accused design will be sufficiently distinct that it will be clear without more that the patentee has not met its burden of proving the two designs would appear “substantially the same” to the ordinary observer . . . . In other instances, when the claimed and accused designs are not plainly dissimilar, resolution of the question whether the ordinary observer would consider the two designs to be substantially the same will benefit from a comparison of the claimed and accused designs with the prior art, as in many of the cases discussed above and in the case at bar. Where there are many examples of similar prior art designs . . . differences between the claimed and accused designs that might not be noticeable in the abstract can become significant to the hypothetical ordinary observer who is conversant with the prior art.

543 F.3d 665, 678–89 (2008). So there are two steps. First, the claimed design and the accused design must be compared. If the designs are “sufficiently distinct that it will be clear without more that the patentee has not met its burden of proving the two designs would appear ‘substantially the same’ to the ordinary observer,” then there is no infringement. Second, if the designs are “not plainly dissimilar,” the prior art (i.e., earlier designs) may be used to narrow the presumptive scope of the patent. This is a one-way ratchet—the prior art can only be used to narrow the presumptive scope of a design patent, not to expand it. Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc. v. Covidien, Inc., 796 F.3d 1312, 1337 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (“[C]omparing the claimed and accused designs with the prior art is beneficial only when the claimed and accused designs are not plainly dissimilar.”) (emphasis added). How does this work in practice? An example might help. Here is the asserted design patent and accused product from Snap-On Inc. v. Harbor Freight Tools USA, Inc., No. 2:16-cv-01265, 2017 WL 44833 (E.D. Wis. Jan. 4, 2017):

Considered in the abstract, these designs might not be plainly dissimilar. But when viewed in light of the prior art, visual differences between the claimed design (top left) and accused design (bottom right) become more apparent:

See id. at *4. The court concluded that the patent owner was not likely to succeed on the merits and denied the patent owner’s motion for a preliminary injunction.

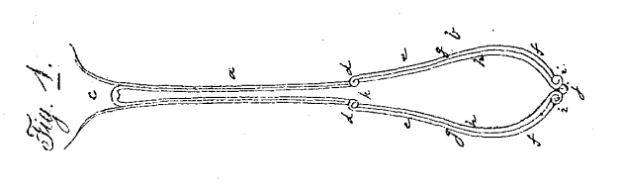

- How close is too close under Egyptian Goddess? In Lin v. Belkin International, Inc., the plaintiff alleged that this USB cable infringed this design patent:

The court granted summary judgment of noninfringement. Based on its own visual review, the court found that the designs were so “sufficiently distinct and plainly dissimilar . . . that no reasonable jury could find the two designs to be substantially the same.” Lin v. Belkin Int’l, Inc., No. 8:16-cv-00628, 2017 WL 2903261, at *6 (C.D. Cal. May 12, 2017).

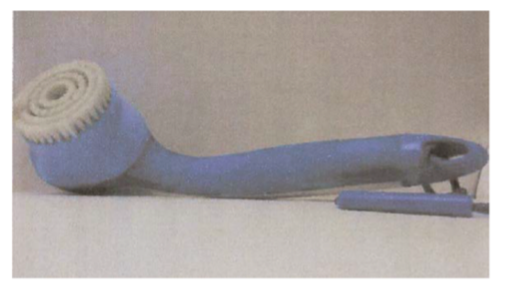

In Wallace v. Ideavillage Products Corp., the plaintiff alleged that this spinning brush infringed this design patent:

The district court granted the defendant’s motion for summary judgment of noninfringement, concluding, upon visual review, that the designs were “sufficiently distinct” and that the plaintiff could not, “as a matter of law, prove that the designs appear substantially the same.” Wallace v. Ideavillage Prods. Corp., No. 2:06-cv-05673, 2014 WL 4637216, at *4 (D.N.J. Sept. 15, 2014), aff’d, 640 F. App’x 970, 972 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

In Performance Designed Products LLC v. Mad Catz, Inc., the plaintiff alleged that this video game controller infringed this design patent:

The judge dismissed the claim with prejudice under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6), concluding that these designs were so “plainly dissimilar” under Egyptian Goddess that any attempt to amend the claim would be “futile.” Performance Designed Prods. LLC v. Mad Catz, Inc., No. 3:16-cv-00629, 2016 WL 3552063, at *6-7 (S.D. Cal. June 29, 2016).

In Boost Oxygen, LLC v. Oxygen Plus, Inc., No. 0:17-cv-05004, 2020 WL 4582253, at *6 (D. Minn. Aug. 10, 2020), the court ruled that this accused product was plainly dissimilar from this patented design:

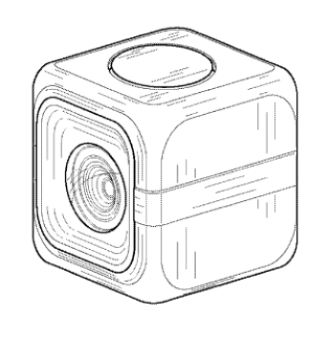

By contrast, in C&A Mktg., Inc. v. GoPro, Inc., No. 1:15-cv-07854, 2016 WL 1626018, at *1 (D.N.J. Apr. 25, 2016), the court ruled that these designs were not plainly dissimilar:

To be clear: A finding that an accused design is “not plainly dissimilar” is not the same as a finding of infringement. Even if the designs are not plainly dissimilar, there is still a second step of the Egyptian Goddess test. At step two, the accused infringer can introduce evidence of prior art designs to narrow the presumptive scope of the asserted patent. And the ultimate test is whether the designs look the same to the ordinary observer. See Sarah Burstein, Intelligent Design & Egyptian Goddess: A Response to Professors Buccafusco, Lemley & Masur, 68 Duke L.J. Online 94 (2019).

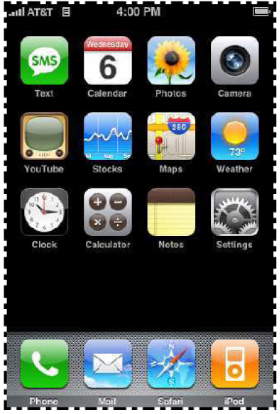

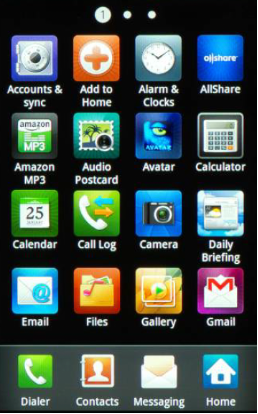

Courts sometimes give—or allow juries to give—design patents a broader scope. For example, in Apple v. Samsung, where the jury found that this design patent for a graphical user interface was infringed by various devices, including this one:

See Amended Verdict Form at 7, Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 5:11-cv-01846 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 24, 2012), ECF 1931. Is the jury’s verdict consistent with the other examples you’ve seen in this chapter? Note: Samsung did not seek summary judgment of noninfringement on this and similar claims. See Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 5:11-cv-01846, 2012 WL 2571719, at *20 (N.D. Cal. June 30, 2012).

- As you can see from these representative examples, design patents have narrow scopes. So why do people want them? One answer is remedies. Design patent owners are entitled to all of the basic patent remedies, such as injunctive relief under § 283 of the Patent Act and “damages adequate to compensate for the infringement, but in no event less than a reasonable royalty” under § 284. But, for certain acts of infringement, design patent owners have an additional remedy—namely, an award of the infringer’s “total profits” under § 289. Note that § 289 provides an alternative form of monetary relief; a design patent owner cannot recover under both § 289 and § 284 for the same act of infringement. Also, while a court may treble a damages award under § 284, it may not treble an award under § 289. Therefore, depending on the circumstances, a § 284 award may well be larger than a § 289 award. This “total profits” remedy has been around since 1887 but it’s still not entirely clear how it should be applied—especially in light of the contemporary broken-line claiming system. See Samsung Elecs. Co., Ltd. v. Apple Inc., 137 S. Ct. 429, 436 (2016) (creating a two-part test for applying § 289 but “declin[ing] to lay out a test for the first step . . . .”). For some suggestions about how courts should apply § 289 post-Samsung, see Pamela Samuelson & Mark Gergen, The Disgorgement Remedy of Design Patent Law, 108 Cal. L. Rev. 183, 184 (2020) and Sarah Burstein, The “Article of Manufacture” Today, 31 Harv. J.L. & Tech. 781, 835 (2018).

B. The Requirements of Patentability

Like other types of inventions, a design must be novel and nonobvious to be patentable. 35 U.S.C. §§ 102, 103. A patentable design must also be “ornamental.” 35 U.S.C. § 171(a). In theory, these might sound like difficult requirements to satisfy. We’ll see how the Federal Circuit has applied them in practice.

High Point Design LLC v. Buyers Direct, Inc.

730 F.3d 1301 (Fed. Cir. 2013)

SCHALL, Circuit Judge.

Buyer’s Direct, Inc. (“BDI”) appeals from a final judgment of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York holding BDI’s asserted design patent invalid on summary judgment and also dismissing BDI’s trade dress claims with prejudice. For the reasons set forth below, we reverse the grant of summary judgment of invalidity . . . and remand for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

Background

I

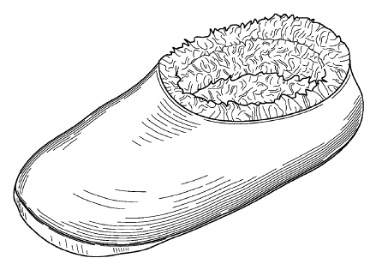

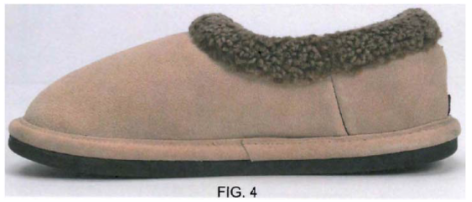

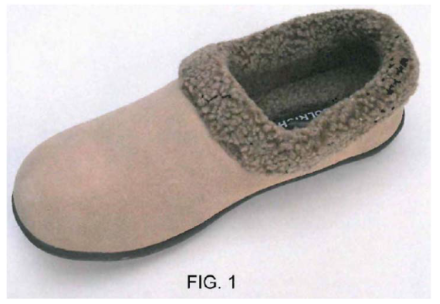

BDI is the owner of U.S. Design Patent No. D598,183 (the “’183 patent”) and the manufacturer of slippers known as SNOOZIES®. An exemplary pair of SNOOZIES® slippers is shown below:

The ’183 patent recites one claim, for “the ornamental design for a slipper, as shown and described.” [One] of the drawings included in the ′183 patent [is] shown below:

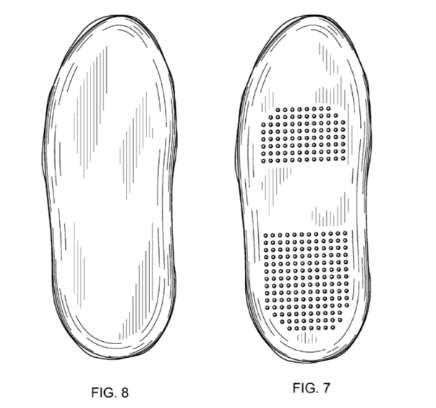

As additional design features, the ’183 patent discloses two different soles: a smooth bottom (as shown in Figure 8) and a sole with two groups of raised dots (as shown in Figure 7):

BDI alleges that SNOOZIES® are an embodiment of the design disclosed in the ’183 patent.

II

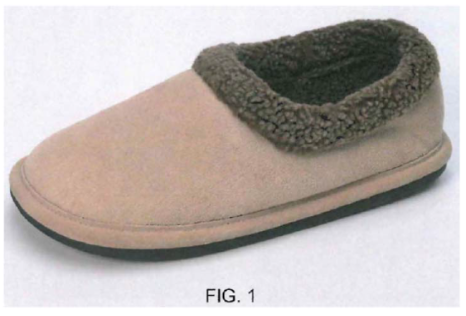

High Point Design LLC (“High Point”) manufactures and distributes the accused FUZZY BABBA® slippers, which are sold through various retailers, including appellees Meijer, Inc., Sears Holdings Corporation, and WalMart Stores, Inc. (collectively, the “Retail Entities”). An exemplary pair of FUZZY BABBA® slippers is shown below:

On June 22, 2011, after becoming aware of the manufacturing and sale of FUZZY BABBA® slippers, BDI sent High Point a cease and desist letter, in which BDI asserted infringement of the ’183 patent. With a responsive letter sent on July 6, 2011, High Point included a copy of a complaint for declaratory judgment that it had filed five days earlier in federal district court. In the complaint, High Point alleged (1) that the manufacturing and sale of FUZZY BABBA® slippers did not infringe the ’183 patent and (2) that the ’183 patent is invalid and/or unenforceable.

In its answer to High Point’s declaratory judgment complaint, filed on December 29, 2011, BDI lodged counterclaims for infringement of the ’183 patent and for infringement of the trade dress found in BDI’s SNOOZIES® slippers. That same day, BDI filed a third-party complaint alleging that the Retail Entities infringed the ’183 patent and infringed BDI’s trade dress based on sales of High Point’s FUZZY BABBA® slippers.

III

On May 15, 2012, the district court granted the motion for summary judgment, holding the ’183 patent invalid on the ground that the design claimed in it was . . . obvious in light of the prior art . . . . The court characterized the ’183 patent as disclosing “slippers with an opening for a foot that contain a fuzzy (fleece) lining and have a smooth outer surface.” As to the prior art, the court found that a consumer apparel company, known as Woolrich, had, prior to the effective filing date of the ’183 patent, sold two different models of footwear: the “Penta” and the “Laurel Hill” (collectively, the “Woolrich Prior Art”). The Penta and the Laurel Hill models are shown in photographs below:

J.A. 486–87 (Penta).

J.A. 490–91 (Laurel Hill).

The [district] court found that the Penta “looks indistinguishable from the drawing shown in the ’183 Patent,” and that the Laurel Hill, “while having certain differences with the Penta slipper that are insubstantial and might be referred to as streamlining, nonetheless has the precise look that an ordinary observer would think of as a physical embodiment of the drawings shown on the ’183 Patent.”

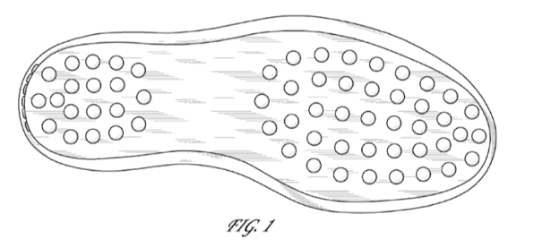

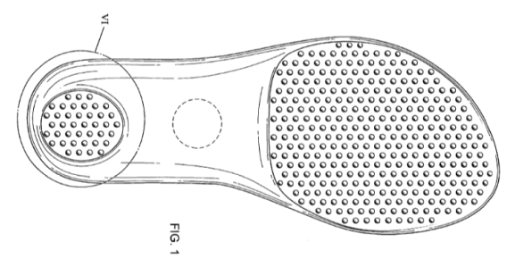

The district court also identified two secondary references—U.S. Design Patent Nos. D566,934 and D540,517 (collectively, the “Secondary References”)—that disclose “slippers with a pattern of small dots on the bottom surface.” Representative drawings from the Secondary References are shown below:

U.S. Design Patent No. D566,934 fig. 1.

U.S. Design Patent No. D540,517 fig. 1. Based on these findings, the court concluded that the design in the ’183 patent was invalid as obvious:

The overall visual effect created by the Woolrich prior art is the same overall visual effect created by the ′183 patent. To an ordinary observer, they are the same slippers. The only difference between the slippers relates to the sole of the slippers, which is quite minor in the context of the overall slipper. Even if, however, this Court were to find that the differences in the sole design were of any note, the design of the dots on the ’183 patent are anticipated by the dots on the Secondary References.

Since both of those design patents were noted on the face of the ’183 patent, and since both relate to slippers, they would have been available to a slipper designer skilled in the art—and would have easily suggested the addition of “dots” to the sole of a slipper. Combining the dots shown on those two design patents with the prior art in the Woolrich slipper would have been obvious to any designer. That combination would have created a slipper with a virtually identical visual impression as the ’183 patent.

Discussion

On appeal, BDI challenges both the grant of summary judgment of invalidity . . . .

II

A

When assessing the potential obviousness of a design patent, a finder of fact employs two distinct steps: first, “one must find a single reference, a something in existence, the design characteristics of which are basically the same as the claimed design”; second, “once this primary reference is found, other references may be used to modify it to create a design that has the same overall visual appearance as the claimed design.” Durling v. Spectrum Furniture Co., 101 F.3d 100, 103 (Fed. Cir. 1996) (internal quotations omitted); see also Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 678 F.3d 1314, 1329 (Fed. Cir. 2012).

Under the first step, a court must both “(1) discern the correct visual impression created by the patented design as a whole; and (2) determine whether there is a single reference that creates ‘basically the same’ visual impression.” Durling, 101 F.3d at 103. The ultimate inquiry in an obviousness analysis is “whether the claimed design would have been obvious to a designer of ordinary skill who designs articles of the type involved.”

B

BDI asserts that the district court erred by using the Woolrich Prior Art as primary references because their design characteristics are not “basically the same as the claimed design,” as required under the first step set forth in Durling. Specifically, BDI relies on the Rake Declaration to argue that various design features distinguish the ’183 patent from the Woolrich Prior Art, including differences in (1) the fleece collars, (2) the height of the sidewalls, and (3) the thickness of the soles. According to BDI, these alleged differences create genuine issues of material facts as to whether the Woolrich Prior Art can properly serve as primary references.

Next, BDI asserts that the district court identified no motivation to modify the Woolrich Prior Art to achieve the “same overall visual appearance as the claimed design,” as required under the second step set forth in Durling. According to BDI, the court erred by ignoring the design features that distinguish the ′183 patent from the Woolrich Prior Art, and finding that the only differences relate to the soles.

BDI also argues that the district court failed to perform a proper obviousness analysis. First, BDI asserts that the court erred by applying an “ordinary observer” standard, because this court’s case law requires application of an “ordinary designer” standard in an obviousness analysis relating to a design patent. Second, BDI argues that the district court failed to properly communicate its reasoning in either step of the obviousness analysis. Finally, BDI asserts that the court erred by not addressing secondary considerations, including copying and commercial sales.

In response, High Point and the Retail Entities (collectively, the “Appellees”) assert that either the Penta or the Laurel Hill could act as the primary reference for the obviousness analysis because they are both “basically the same as the claimed design,” which, according to the Appellees, is all that is required under the first step. The Appellees assert that BDI seeks to apply a “virtual identity” standard in the first step, rather than the proper standard, which allows for minor differences. According to the Appellees, under this court’s case law, a district court can assess the “overall visual appearance,” as required by the second step under Durling, without expert testimony and “almost instinctively.”

The Appellees also argue that the district court properly discounted the Rake Declaration because obviousness should be assessed from the vantage point of the ordinary observer, not an ordinary designer such as Mr. Rake. According to the Appellees, the district court properly applied the ordinary observer standard to find obviousness based on the combination of either the Penta or the Laurel Hill with the Secondary References.

As to secondary considerations, the Appellees argue that BDI failed to show the nexus necessary to demonstrate that either the alleged copying or the commercial sale of SNOOZIES® support the nonobviousness of the ′183 patent. Specifically, the Appellees assert that BDI has not established that SNOOZIES® actually embody the ’183 patent, as is necessary to support BDI’s nonobviousness arguments.

C

We first address the standard applied by the district court here. The use of an “ordinary observer” standard to assess the potential obviousness of a design patent runs contrary to the precedent of this court and our predecessor court, under which the obviousness of a design patent must, instead, be assessed from the viewpoint of an ordinary designer. Given this precedent, the district court erred in applying the ordinary observer standard to assess the obviousness of the design patent at issue.

Although obviousness is assessed from the vantage point of an ordinary designer in the art, “an expert’s opinion on the legal conclusion of obviousness is neither necessary nor controlling.” That said, an expert’s opinion may be relevant to the factual aspects of the analysis leading to that legal conclusion. For that reason, the district court erred by categorically disregarding the Rake Declaration.

We now turn to what we conclude were additional errors in the district court’s application of the two-step analysis set forth in Durling. As to the first part of the first step—”discerning the correct visual impression created by the patented design as a whole”—the district court erred by failing to translate the design of the ’183 patent into a verbal description. See Durling, 101 F.3d at 103 (“From this translation, the parties and appellate courts can discern the internal reasoning employed by the trial court to reach its decision as to whether or not a prior art design is basically the same as the claimed design.”). The closest to the necessary description was the court’s comment characterizing the design in the ’183 patent as “slippers with an opening for a foot that can contain a fuzzy (fleece) lining and have a smooth outer surface.” This, however, represents “too high a level of abstraction” by failing to focus “on the distinctive visual appearances of the reference and the claimed design.” On remand, the district court should add sufficient detail to its verbal description of the claimed design to evoke a visual image consonant with that design.

As to the second part of the first step—”determining whether there is a single reference that creates ‘basically the same’ visual impression”—the court erred by failing to provide its reasoning, as required under this court’s precedent. Absent such reasoning, we cannot discern how the district court concluded that the Woolrich Prior Art was “basically the same as the claimed design,” so that either design could act as a primary reference. On remand, the district court should do a side-by-side comparison of the two designs to determine if they create the same visual impression. See, e.g., Apple, 678 F.3d at 1330 (comparing images of the claimed design to images of the asserted primary references). In addition, based on the record before us, there appear to be genuine issues of material fact as to whether the Woolrich Prior Art are, in fact, proper primary references. For this additional reason, summary judgment must be reversed.

To the extent that the obviousness of the ’183 patent remains at issue on remand, the district court will, after properly completing the first step under Durling, be in a better position to assess whether or not the Woolrich Prior Art, modified by the Secondary References, provide a design with the “same overall visual appearance as the claimed design,” as required under the second step of Durling.3

3 Having setting forth the proper framework for the obviousness analysis, we take no position on whether the district court could or should find obviousness under the proper standard.

Finally, we turn to secondary considerations, which the district court did not address in the Final Decision. This court has held that “evidence rising out of the so-called ‘secondary considerations’ must always when present be considered en route to a determination of obviousness.” Here, BDI alleged both commercial success of the claimed design as well as copying. To the extent that the obviousness of the ’183 patent remains at issue on remand, the district court should address any evidence of secondary considerations.

For the foregoing reasons, we reverse the grant of summary judgment of obviousness and remand the case to the district court.

Context & Application

1. What test does the Federal Circuit use to evaluate whether or not a claimed design is obvious?

2. The “primary reference” is sometimes called a “Rosen reference.” In In re Rosen, the C.C.P.A. held that “there must be a reference, a something in existence, the design characteristics of which are basically the same as the claimed design in order to support a holding of obviousness.” 673 F.2d 388, 391 (C.C.P.A. 1982). This reference is required “whether the holding is based on the basic reference alone or on the basic reference in view of modifications suggested by secondary references.” Id. Once a proper primary reference is identified, “other references may be used to modify it to create a design that has the same overall visual appearance as the claimed design.” Durling v. Spectrum Furniture Co., 101 F.3d 100, 103 (Fed. Cir. 1996). But “secondary references may only be used to modify the primary reference if they are so related to the primary reference that the appearance of certain ornamental features in one would suggest the application of those features to the other.” Id. What does that mean? The case law is less than clear. And in light of the high standard of visual similarity the Federal Circuit requires for primary references, few cases reach this second step at all. For more on these issues, see Sarah Burstein, Visual Invention, 16 Lewis & Clark L. Rev. 169, 214 (2012).

3. The court states in High Point “evidence rising out of the so-called ‘secondary considerations’ must always when present be considered en route to a determination of obviousness.” These secondary considerations include commercial success and copying. Are these considerations a good fit for designs?

High Point Design LLC v. Buyers Direct, Inc.

621 F. App’x 632 (Fed. Cir. 2015)

CHEN, Circuit Judge.

This is the second time this case has been appealed to our court. In High Point Design LLC v. Buyers Direct, Inc., 730 F.3d 1301 (Fed. Cir. 2013) (“High Point I”), we reversed the . . . grant of summary judgment of invalidity of the design patent belonging to Buyers Direct, Inc. (BDI). . . .

On remand, the district court again granted summary judgment, finding that: (1) the asserted patent was anticipated; (2) the accused products did not infringe; . . . .

BDI challenges each of these determinations on appeal. For the reasons set forth below, we reverse summary judgment of invalidity [and] affirm summary judgment of non-infringement . . . .

I

The background of the case is set forth in High Point I . . . . We recount below only the facts pertinent to the issues on appeal.

BDI owns a design patent for the ornamental appearance of a fuzzy slipper, U.S. Patent No. D598,183 (the D’183 patent). The D’183 patent is entitled “Slipper,” and recites one claim for “the ornamental design for a slipper, as shown and described” in eight figures. . . .

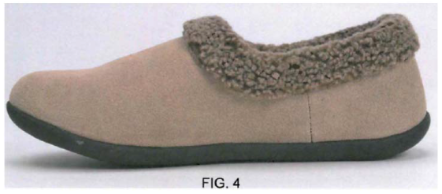

The claimed design discloses two embodiments for the slipper soles. One embodiment has a sole with two groups of raised dots, and the other has a sole with a smooth bottom.

BDI manufactures a slipper called the SNOOZIE® (Snoozie), which it contends is an embodiment of the design disclosed in the D’183 patent. . . .

High Point Design LLC (High Point) manufactures and distributes the accused FUZZY BABBA® slipper (Fuzzy Babba). . . .

D

On remand, the district court again granted summary judgment of invalidity. This time the district court found that the D’183 patent was anticipated by the Woolrich Prior Art. The district court offered the following description of the claimed design in support of its decision:

To an ordinary observer, the ’183 Patent is the design of a slipper with a formed body, a protrusion of fuzz or fluff, and a sole with some solidity. The outside of the slipper appears durable and looks to be made of a relatively tough material; the inside looks soft, plush, and made of a warm material. The sole appears to be fairly thick and looks sturdy.

Addressing each of the prior art designs in turn, the district court first determined that the Laurel Hill anticipated because it also had “a structured body, a soft-looking fluff surrounding the opening of the slipper, and a sole that appears durable and fairly thick.” The district court then found that the Penta also anticipated, concluding that the Penta was even more similar to the D’183 patent than the Laurel Hill. The court found that the Penta “conveys the visual effect of a slipper, the body and sole of which have some defined shape and solidity but which has a protrusion of fluff or fuzz emanating from the foot opening.” Although the district court noted that a close study of the patented and prior art designs revealed differences, those differences were “minor” and insufficient to defeat anticipation.

The district court also ruled in favor of High Point on grounds that the Fuzzy Babba slipper did not infringe the patented design. In particular, the district court found:

The Fuzzy Babba conveys the visual effect of an entirely soft and malleable body with an indistinguishable sole; it is soft and malleable all around. In contrast, the visual effect of the ’183 Patent is of a formed body and sole with some solidity; and a body distinct from the sole.

II

A

We turn first to the district court’s grant of summary judgment on anticipation.

Design patents are presumed to be valid. 35 U.S.C. § 282(a). A party seeking to invalidate a patent on the basis of anticipation must do so by clear and convincing evidence. Design patent anticipation requires a showing that a single prior art reference is “identical in all material respects” to the claimed invention. In other words, the two designs must be substantially the same. Two designs are substantially the same “if the resemblance is such as to deceive an ordinary observer, inducing him to purchase one supposing it to be the other.” Anticipation is a question of fact. Summary judgment is proper only when the evidence underlying anticipation is clear and convincing such that no reasonable fact-finder could find otherwise.

Viewing all evidence in the light most favorable to the non-moving party—BDI—we conclude that a reasonable jury could have found there was not clear and convincing evidence of anticipation.

In High Point I, we instructed that on remand, the district court should “add sufficient detail to its verbal description of the claimed design to evoke a visual image consonant with the claimed design.” We also instructed that the district court should perform a side-by-side comparison of the claimed and prior art designs as part of the proper obviousness determination. Notably, we cautioned that there appeared to be “genuine issues of material fact as to whether the Woolrich Prior Art are, in fact, proper primary references” for obviousness purposes under 35 U.S.C. § 103.

On remand, the district court did not perform a side-by-side comparison, but concluded that the claimed and prior art designs share the “same characteristics” because they share “a structured body, a soft-looking fluff surrounding the opening of the slipper, and a sole that appears durable and fairly thick.”

We find again that the district court fundamentally erred in its analysis by analyzing the designs from “too high a level of abstraction” and failing to focus “on the distinctive visual appearances of the reference and the claimed design.” Specifically, the court’s description does little more than point out the main concepts of the claimed design: a structured slipper having fuzzy material at the foot opening. In doing so, the court failed to properly consider the ornamental aspects of the designs at issue. There are numerous such features in the body, the fuzzy material, and the sole of the designs, all of which were overlooked in the district court’s analysis.

For example, there are meaningful differences between the curvatures of the slipper body designs. The body of the patented design has a distinct ‘S’ curve between the foot opening and the front of the slipper as viewed from the side, which ends in a downward slope toward the front of the body. By contrast, the Laurel Hill has a prominent upward curve near the front. The Penta is also different because it has a noticeably flatter, more even slope from the foot opening towards the front.

There are also clear differences between the protruding fuzz of the claimed and prior art designs. In particular, the Woolrich Prior Art appears to differ from the claims in that both prior art slippers have a pronounced fleece overlap oriented outward and which obscures the top edge of the foot opening. By contrast, no such overlap is visible in the patented design.

We also find that the district court failed to take into consideration the substantial differences between the ornamental aspects of the soles of the claimed design and the prior art designs. As we stated in Contessa Food Prods., Inc. v. Conagra, Inc., “our precedent makes clear that all of the ornamental features illustrated in the figures must be considered in evaluating design patent infringement.” 282 F.3d 1370, 1378 (Fed. Cir. 2002).

The district court did not address the ornamental aspects of the soles in the Remand Order, but stated in the 2012 Order that “the only difference between the slippers relates to the sole of the slippers, which is quite minor in the context of the overall slipper.” We disagree. There are unmistakable differences between the sole design of the D’183 patent and the Woolrich Prior Art. The patent claims one embodiment, shown in Figure 7, where the sole has dots. Those dots are arranged in a uniformly spaced pattern of rows and columns in two separate groups. One group is positioned closer to the front of the slipper, and narrows slightly toward the toe area. The other group is placed closer to the rear, and has a corresponding taper toward the rear area. The other embodiment, shown in Figure 8, has a smooth sole. Neither of the Woolrich Prior Art designs has either of these design components.

The prior art designs instead each have their own distinct ornamental designs. The Laurel Hill sole has embedded within it images of four trees and two moose. The Laurel Hill also has a grooved border not present in the claimed design. The Penta sole has a large “WOOLRICH” image imprinted thereon and is also decorated with a distinct pattern. Like the Laurel Hill—but unlike the claimed design—the Penta also has a grooved border.

As we cautioned in High Point I, there appeared to be genuine issues of material fact regarding whether the Woolrich Prior Art properly served as base references under this court’s obviousness law. We now similarly hold that the evidence is not so clear and convincing such that a reasonable fact-finder could not find for BDI on anticipation. For these reasons, we reverse summary judgment of invalidity.

B

We turn next to the district court’s grant of summary judgment of non-infringement.

Infringement is a question of fact and must be proved by a preponderance of the evidence. Summary judgment of non-infringement is appropriate when no reasonable fact-finder could find the accused design substantially similar to the claimed design.

Infringement of design patents is judged by the same test as anticipation—whether two designs are “substantially the same.” See Egyptian Goddess, 543 F.3d at 678 (adopting test set forth in Gorham, 81 U.S. at 528 as sole test for design patent infringement). Under Egyptian Goddess, where the claimed and accused designs are “sufficiently distinct” and “plainly dissimilar,” the patentee does not meet its burden of proving infringement. Only if the claimed and accused designs are not plainly dissimilar does the inquiry potentially benefit from comparison of the claimed and the accused designs . . . with the prior art. We agree with the district court that it is not necessary to resort to a comparison with the prior art in ruling on infringement here.

The district court conducted a side-by-side comparison between the claimed design and the accused Fuzzy Babba slippers, and concluded that “the Fuzzy Babba’s appearance evokes a soft, gentle image, while the D’183 patent appears robust and durable.” Finding that a consumer would not confuse the two designs, the court then granted summary judgment of non-infringement.

We conclude that the patented and accused designs bring to mind different impressions. The Fuzzy Babba design appears soft and formless, whereas the claimed design appears structured and formed. These differences are reflected in the ornamental aspects of each of the designs. For example, the side profile of the Fuzzy Babba shows a relatively smooth, downward slope from the rear toward the front area of the slipper. By contrast, the D’183 patent design has a relatively defined, curved opening that is lower in the middle and higher at the edges. Further, the Fuzzy Babba has a relatively straight rear line, whereas the rear of [the] claimed design bulges outward. The front areas of the two designs are also substantially dissimilar. The Fuzzy Babba has a relatively flatly sloping side profile, whereas the patented design has a curved profile, roughly following in an ‘S’ curve shape.

As we did with respect to invalidity, we also find that there are meaningful differences in the soles which affect the overall visual effect of the two designs. Unlike the D’183 patent design, the Fuzzy has a continuous distribution of dots throughout almost the entire length of the sole. These dots are of a constant width and in one group, in contrast to the varying width of dot columns displayed in Figure 7, and in further contrast to the embodiment in Figure 8 that has a smooth sole and no dots.

We recognize that both designs essentially consist of a slipper with a fuzzy portion extending upward out of the foot opening. Such high-level similarities, however, are not sufficient to demonstrate infringement.

BDI also argues that the district court erred by not performing a comparison of the accused Fuzzy Babba slipper to BDI’s alleged commercial embodiment, the Snoozie. We have long-cautioned that it is generally improper to determine infringement by comparing an accused product with the patentee’s purported commercial embodiment.

If a patentee is able to show that there is no substantial difference between the claimed design and the purported commercial embodiment, a comparison between that embodiment and the accused design is permissible. Contrary to BDI’s suggestion, however, we have never mandated such comparisons and decline to do so here. The proper test for infringement is performed by measuring the accused products against the claimed design.

BDI also argues that the district court erred by failing to take into account how the accused products appeared as worn. We disagree. Even as worn, there are meaningful differences in the visual impression between the two designs. The Fuzzy Babba lacks the distinctive ‘S’ curve of the front area visible in Figure 4 of the claimed design. Moreover, the protrusion of fuzz in the Fuzzy Babba remains thicker toward the back then toward the front of the foot opening. And critically, there remain the aforementioned differences in the soles of the two designs.

For all these reasons, we affirm the district court’s grant of summary judgment of non-infringement.

Context & Application

1. What is the Federal Circuit’s test for anticipation of a design patent? Is it an easy standard for a challenger to meet?

2. When can a patentee’s commercial embodiment be used in the infringement inquiry? Who has the burden of proving that a product is, in fact, a commercial embodiment of a claimed design?

3. In High Point, the court mentioned that the patent-in-suit “disclose[d] two embodiments for the slipper soles.” Although a design patent can only have one claim, “[m]ore than one embodiment of a design may be protected by a single claim. However, such embodiments may be presented only if they involve a single inventive concept according to the nonstatutory double patenting practice for designs.” MPEP § 1504.05 (citing In re Rubinfield, 270 F.2d 391 (C.C.P.A. 1959)). What does it mean to have the same inventive concept? To be a different “embodiment” of the same “design”? It’s not clear. In practice, some attorneys report that it’s really a matter of what you can “get past the examiner.” But overaggressive embodiment claiming is a risky strategy, because the doctrine of prosecution history estoppel also applies to design patents. See Pac. Coast Marine Windshields Ltd. v. Malibu Boats, LLC, 739 F.3d 694, 697 (Fed. Cir. 2014).

4. In a portion of High Point I that was omitted above, the Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s determination that the claimed design was invalid as “functional.” See 730 F.3d 1301, 1317 (Fed. Cir. 2013). The Federal Circuit has interpreted the design patent requirement of ornamentality, see 35 U.S.C. § 171(a), as being the opposite of “functional.” But the case law is less than clear on the issue of how to analyze functionality. (One word of warning for those who have studied trademark law: The word “functional” does not mean the same thing in contemporary design patent law that it does in contemporary trademark law. See Sarah Burstein, Faux Amis in Design Law, 105 Trademark Rep. 1455 (2015).)

Many cases say that a design is not functional if there are alternative designs. See, e.g., Best Lock Corp. v. Ilco Unican Corp., 94 F.3d 1563, 1566 (Fed. Cir. 1996) (“[I]f the design claimed in a design patent is dictated solely by the function of the article of manufacture, the patent is invalid because the design is not ornamental. A design is not dictated solely by its function when alternative designs for the article of manufacture are available.”). A few other cases, citing dicta from Berry Sterling Corp. v. Pescor Plastics, Inc., 122 F.3d 1452 (Fed. Cir. 1997), say that other factors can be used to evaluate design patent functionality. In a recent decision, the court summarized—and attempted to reconcile—these different lines of cases as follows:

In determining whether a claimed design is primarily functional, “the function of the article itself must not be confused with ‘functionality’ of the design of the article.” Hupp v. Siroflex of Am., Inc., 122 F.3d 1456, 1462 (Fed. Cir. 1997). In Hupp, we separated the function inherent in a concrete mold—producing a simulated stone pathway by molding concrete—from the particular pattern of the stone produced by the mold itself—an aesthetic design choice. . . . Because there was no utilitarian reason the mold had to impress the particular claimed rock walkway pattern into the concrete, we determined that the claimed design was “primarily ornamental,” and not invalid as functional. In High Point Design LLC v. Buyers Direct, Inc., we found that the district court had incorrectly relied on the functional aspects of a slipper—a seam connecting two components, a curved front accommodating the foot, an opening facilitating ingress and egress of the foot, a forward lean of the heel keeping the heel in place, and a fleece interior providing warmth—to find the particular ornamental design of that slipper to be impermissibly functional. 730 F.3d 1301, 1316 (Fed. Cir. 2013). We explained that a claimed design was not invalid as functional simply because the “primary features” of the design could perform functions. . . .

By contrast, in Best Lock, we affirmed a district court’s determination that a design patent to the blade of a key was invalid as functional, finding no clear error in the district court’s conclusion that the claimed key blade design was dictated by functional concerns. 94 F.3d at 1567. In Best Lock, the claimed design was limited to a specific shape of a blank key blade. The parties did not dispute that the claimed key blade shape was designed specifically to perform its intended function—to fit into a similarly-shaped cylinder lock keyhole. Further, the patentee presented no evidence of alternative compatible key blade designs, admitting that no differently-shaped key blade could fit into the keyhole of the corresponding cylinder lock. Because no alternative design would allow the underlying article to perform its intended function, we determined the district court did not clearly err by finding that the claimed key blade design was dictated by function, and therefore invalid.

. . .

We have not mandated applying any particular test for determining whether a claimed design is dictated by its function and therefore impermissibly functional. We have often focused, however, on the availability of alternative designs as an important—if not dispositive—factor in evaluating the legal functionality of a claimed design. For example, the district court in L.A. Gear referenced the evidence of many alternative designs that accomplished the same functionality associated with the underlying athletic sneaker. 988 F.2d at 1123. In view of that evidence, we noted that “when there are several ways to achieve the function of an article of manufacture, the design of the article is more likely to serve a primarily ornamental purpose.” Id. See also Rosco, 304 F.3d at 1378 (“[I]f other designs could produce the same or similar functional capabilities, the design of the article in question is likely ornamental, not functional.”); Best Lock, 94 F.3d at 1566 (same); Hupp, 122 F.3d at 1460 (same).

Here, the district court appeared to discount the existence and availability of alternative designs in determining that the claimed Design Patents were “primarily functional” based on its evaluation of the five considerations identified in PHG, 469 F.3d at 1366 (quoting Berry Sterling, 122 F.3d at 1456). In Berry Sterling, we vacated and remanded a district court’s grant of summary judgment of invalidity where it had failed to “elicit the appropriate factual underpinnings for a determination of invalidity of a design patent due to functionality.” 122 F.3d at 1454. In our instructions on remand, we explained that where the existence of alternative designs is not dispositive of the invalidity inquiry, the district court may look to several other factors for its analysis:

whether the protected design represents the best design; whether alternative designs would adversely affect the utility of the specified article; whether there are any concomitant utility patents; whether the advertising touts particular features of the design as having specific utility; and whether there are any elements in the design or an overall appearance clearly not dictated by function.

Id. at 1456. We explained that evaluating these other considerations “might” be relevant to assessing whether the overall appearance of a claimed design is dictated by functional considerations. Id. Thus, while the Berry Sterling factors can provide useful guidance, an inquiry into whether a claimed design is primarily functional should begin with an inquiry into the existence of alternative designs.

Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc. v. Covidien, Inc., 796 F.3d 1312, 1328–30 (Fed. Cir. 2015). What is the status of the Berry Sterling factors following Ethicon? When (and how) should courts use them? Is the court’s attempt to reconcile these lines of precedent convincing? For more on design patent functionality—and on design patents in general—see Chapter 12 in Sarah Burstein, Sarah R. Wasserman Rajec & Andres Sawicki, Patent Law: An Open-Access Casebook (2021).