“What is a library?”

I had just given an invited talk about distinctive children’s materials in nineteenth- and twentieth-century public libraries. When the floor was opened for Q&A, an eminent scholar in the audience raised his hand. He didn’t ask about my argument that public libraries have historically included toys rather than restricting their collections to books, or even about the historical games and toys for children in the research collection we were both there to use. Instead, he asked me this fundamental question: “What is a library?”

At that moment, the idea that libraries depend on human intermediation to create collections of materials and to help people use them, a core idea from my library school education, didn’t seem germane. A series of images and experiences, instead of a ready answer, came to me.

The first library I had worked at was an elementary school library, barely more than a single room, lined by bookshelves, with tables where students from kindergarten through grade five could sit and work, plus a few stations where we could view short microfilm movies. I was all of nine years old, and each week, I spent an hour at the circulation desk, stamping other students’ books with due dates, then filing circulation and card catalog cards. This library was where we gathered information for the papers we wrote and found books we wanted to read that had nothing to do with our homework. Years later, its clean lines and spare furnishings lingered in my mind.

The first public library where I worked in reference services was considerably larger; not only was the building larger, it was only one library in a system of twelve sites around the city, including the county jail. The children’s room was on a separate floor, far from the reference desk where paraprofessionals worked alongside degreed librarians, as were the cataloging and technical services departments. In this library, the reference shelves took up more space than all the bookshelves in my elementary school library. Comprised of encyclopedias, directories, almanacs, maps, and myriad other specialized volumes, this collection of non-circulating resources surrounded the reference desk on three sides, extending behind the desk where we waited to answer patron questions. In a pre-internet era, reference books were kept nearby because they were frequently needed during the course of the day to answer the many questions that users arrived with. Sometimes the line of people who needed our help finding books and information was five or six people long in front of each librarian at the desk; it was when those lines were longest that the phone rang most persistently, too. If someone wanted a newspaper article that was more than a few months old, we helped them locate the appropriate microfilm reel and thread the balky machines that made it possible to read and print that medium. Questions came from parents helping their children with homework, from local business owners, and senior citizens who were filling their days with whatever the library could provide. One day, a homeless man asked for a copy of a poem he only partly remembered. There were patterns to those busy days, and a lot of variety as well.

During a year between graduate degrees, I worked at a law firm library, which is one of the many kinds of special libraries. The collection was shelved across three floors of a downtown skyscraper; the firm had offices on the thirty-fourth, thirty-fifth, and thirty-sixth floors. The office I shared with another member of the library staff had something no other library where I’d been employed had – both a computer terminal and a laser printer. The presence of this now normal technology would result, in university and public libraries, in a new acronym: OPAC, which stood for Online Public Access Catalog. (In another moment of Iowa library history, it is believed that Iowa City Public Library was the first public library west of the Mississippi River to offer its patrons this technology).[1] When a famous musician who was a client came to the office, he stood out, in part because his leather jacket and jeans were an obvious departure from the firm’s dress code. Everyone wore suits; the dress code required that men wear ties, and women were not allowed to come to the office with bare legs. The only people who used our multi-storied library, either coming to us with questions or borrowing volumes directly from the polished wooden shelves, were the attorneys and staff who worked for the firm. The questions pertained to the areas of law that were the firm’s specializations and sometimes current events that contextualized these issues. The entire staff was trained in matters like confidentiality of the firm’s cases and professionalism through videos that we sat through together, because these subjects were integral to how the firm functioned. Once, a lawyer wanted a literary work, so the head librarian dispatched me to the nearby university library for a book that would provide it. Both the head librarian and I knew that this was a subject matter that I was distinctively suited for, with a master’s in literature rather than library science on my résumé. At the university library, I selected what I knew was an authoritative edition of the poet’s work and returned to the firm to explain its reliability and contextual information to the secretary who would give the material to her boss during an opening in his schedule. Volume in hand, she now told me that he needed to verify a quotation for a presentation (in other words, I had provided a Norton edition, when Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations would have done, a lesson in one of the perpetual problems of reference work – the need to clarify, tactfully and specifically, the nature of the reference question).

It was perhaps inevitable that I moved back to an instructional environment, working as a graduate assistant at the university where I earned my master’s in library science. My responsibilities were to provide individual assistance to undergraduates working on their first college-level assignments, show faculty members our then-new full-text databases, and maintain a small, specialized part of the reference collection as I completed my professional degree. Some of my peers from my library school classes worked in cataloging, government documents, and other divisions of the library. Regardless of where in the eleven-story library we worked, we all felt lucky to be there; we were gaining experience in librarianship, and we were working with librarians whom we hoped to emulate someday. The full-time librarians understood our status as people learning librarianship, and they modeled best practices when interacting with patrons, sometimes pausing to explain a database’s quirks or why they chose one resource instead of another that seemed on topic once a patron’s question had been answered.

All of my previous work in libraries, whether as a student volunteer or staff, was different from the research center where we were that spring day, with its distinctive collections that had brought me, the eminent scholar who had asked the question, and dozens of other researchers to Massachusetts. It is the kind we refer to as a special collections library, with archival holdings as well as preserved historical publications of various sorts. With its rare historical materials, some not available anywhere else, it had a non-circulating collection and expert librarians or curators who acquired material, promoted those holdings to a wider community, and aided on-site researchers with their specialized research projects. Researchers’ reactions varied from determined concentration on materials they’d only be able to use during their limited time there, to amazement at what librarians who knew the collection could find for them, to moments of distracted delight at the resources other researchers had spread across their desks.

In retrospect, I didn’t have a ready, non-library-school answer for that scholar because the work I and other librarians had done in each of these settings differed. Sometimes the library’s content varied. Sometimes it was the user profile that changed. Sometimes it was how much work librarians did for users, with some libraries serving to “save the time of the reader,” to use one of Ranganathan’s laws of the profession, and others prioritizing teaching users to locate information so that they would not depend on librarians every time they needed library resources.[2] Sometimes, in other words, it is easier to say what a library is not. A library is not what Susan Orlean first suggests in The Library Book, when she writes, “It seems simple to define what a library is – namely, it is a storeroom of books.”[3] Even when Orlean acknowledges that “The more time I spent at Central [Branch of the Los Angeles Public Library], the more I realized that a library is an intricate machine, a contraption of whirring gears,” she only partially reflects the realities of what a library does for its community.[4] There is more to any library than her mechanical metaphor suggests, but I think many librarians would find her description of the library as “an easy place to be when you have no place you need to go and a desire to be invisible” a more apt description than the two previous images from her book.[5] Orlean’s third characterization begins to consider the people who come to the library, including the fact that they might seek refuge rather than information or a book there; it centers the library user as a reason for a library’s existence.[6]

Orlean is not the only person to confuse what a library holds with what it is. There are misperceptions of what a library is, what librarians do, and myths about libraries’ origins. If you spend much time with people who love libraries, you’ll hear people lament the fabled Library of Alexandria and the loss of its expansive contents to fire; scholars believe, however, that its story is far more complex than one of a complete collection followed by complete loss[7] The idea that Ben Franklin, eighteenth-century publisher, inventor, and later U.S. diplomat, created the first public library is one popular story about the way libraries developed in this country; however, what Franklin and his colleagues created was a subscription library, or one that depends on users’ ability to pay a fee in order to borrow books. You’ll encounter people who both assert that librarians’ knowledge is limited to a nineteenth-century organizational scheme, the Dewey Decimal System, or conversely that since everything is on the Internet, we don’t need libraries anymore.[8] You’ll be confronted by people who insist that libraries should only contain good books, the way they were thought to do in the past, a story told with increasing insistence in recent years, even though this notion has seldom reflected actual library collections.[9] Even in 1952, when librarians who provided services to teens were in the early years of their efforts to create a more consistent professional identity for themselves, they dealt with concerns about the appropriateness of the materials they offered teens. That year, the program for the ALA Annual Conference includes a panel titled, “Touchy Areas in Book Selection – a panel discussion.”[10] These all-too-common misunderstandings, some of them glib and others more consequential, are one reason that we need to be able to explain what libraries are and what librarians do.

The past, too, is another reason we need to be able to speak about our aims and aspirations for library services. Numerous researchers have constructed stories of exclusion and prejudice in the history of our field, and we’ll learn about those histories. A broad tendency exhibited by many, though certainly not all, librarians can be described as a focus on books rather than on users. In the past, having a collection of good books was a priority, sometimes to the exclusion of users’ wants and needs. Award-winning novelist Tony Hillerman (1925-2008) grew up in Sacred Heart, Oklahoma, a town without a library. He and others there relied on a “mimeographed catalog of the state library” to order books by mail. The process worked this way, according to Hillerman:

You would order Captain Blood, Death on Horseback, Tom Swift and His Electric Runabout, Flying Aces, and Treasure Island. A month later, a package would arrive. Inside would be a mimeographed letter signed by the librarian: I regret to inform you that the volumes you request are not on our shelves at this time. I have substituted volumes that should meet your needs.[11]

What did the state librarian send young Tony Hillerman? He often received books like “History of the Masonic Order in Oklahoma, Horticultural Chemistry, Modern Dairy Management, a biography of William Jennings Bryan, and the Lord North translation of Plutarch’s Lives of Famous and Illustrious Men of Greece and Rome.”[12]

Familiarity with these early twentieth-century titles isn’t necessary to sense the mismatch between what Hillerman as a boy wanted and what the librarian sent him. (Our literature on reader's advisory is filled with similar examples of failed efforts to respond meaningfully to patron’s expressed interests).[13]

Although there were certainly librarians who were sympathetic to young people’s desires for action-packed novels, the professional literature of earlier eras tends to focus on good books that would help people gain the education that they would have missed out on when they went to work, often by age fourteen. Until well into the twentieth century, it was not uncommon for professional librarians to decide that they knew better than library users did what the latter needed, just one example of how our professional values change over time.

While we tend to use the word library in its singular form, so often preceded by the definite article the, libraries are plentiful, both in number and in what they do. Historian Wayne Wiegand has remarked that, “The United States has more public libraries than it has McDonald’s restaurants.”[14] The vast numbers of libraries are important because, as Gregory Leazer argues, U.S. libraries have long functioned as “‘a network of inter-connected libraries working together'” through activities like shared cataloging norms and records.[15] There are also multiple categories of libraries, varied in their locations and their service communities, and even the libraries within a particular category may differ from one another. (Historically, we have recognized four broad kinds of libraries, which have multiple departments and often further specializations as well: Public libraries, academic libraries, special libraries, and school libraries.) We also see people who have careers in information science and data science, which have come to be regarded as cognate disciplines to our field. Differences between libraries have unfolded over time and in response to library users’ needs, in tandem with our profession’s ideas about its roles, its best resources, and its strategies for interacting with user communities. Your learning, in classes and in conversations with librarians at conferences and where you work, positions you to join the professional discussion of how things are, how they have been, and how they should be in the future.

Your decisions about where you work can reflect the nexus of community and professional values that inform services. Your interest in working with different types of users, whether other professionals with their own specializations, children who are learning how to learn, or anyone who walks through the door, also suggests the kind of library you will be most interested in. You may begin your degree work knowing what kind of library you aspire to work in, or you may find it as you progress through your courses in this degree program. You may also be one of many librarians who know that this degree will help them learn about the issues that are important and interesting to them; their aim is to find the best match between those topics and the work available in the communities where they already live.

People will ask you what the library does or what you do as a librarian, sometimes when you least expect it. Sometimes those people will be library users; sometimes they will be government officials or library funders. They may be potential partners in the kinds of work your library does in its community. They may be people who haven’t used a library in years. In each instance, you’ll want to reply with a succinct, non-technical explanation that reflects both the library’s overall purpose and a specific aim that responds to their needs or interests (your library’s mission statement or your department’s current priority, whether summer reading programs, job help, or opening a new library branch, will likely help you shape your response). Your response may also change over time, as your own work and the needs of your library’s users evolve and adapt to changes in the community or the world. However you choose to respond to the question, “What is a library?” you may find that in explaining the work of your library to others, you improve and increase your own sense of what a library is and can do.

I believe that as librarians, some of our best learning happens when we work together and share our perspectives on the field’s ideals and its day-to-day actualities. This course and this text rest on the idea that we learn about librarianship together, in conversation, whether that conversation happens in the same room, in an online discussion space, at professional conferences, or through engagement with the professional literature of our field. Librarianship is a vast and changing field. It can only be learned over time. We want to see you join in that conversation, whether you’ve had a career in another field, whether you’re a paraprofessional with many years of experience preparing to move into new roles in your library, or whether your primary experience of libraries is as a community member. As we spend time in this field, the librarians we talk with share their experiences, help direct our attention to resources that may be helpful, criticize ideas we need to reconsider, and more. During this course, you’ll be part of a series of conversations, and we aspire to invite you to share parts of those contributions with future students, as we revise, revisit, and expand this book.

Starting the Conversation: A Response by Nancy Henke, MA, MLIS (2023)

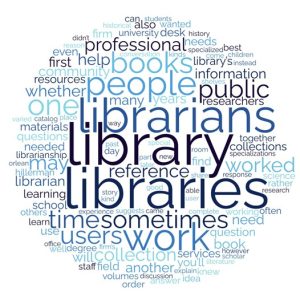

When tasked with responding to this introductory chapter, I realized how vague and imprecise my own definition of a library is. What would I say if someone asked me to define it? So I decided to examine the language of the chapter to consider how a seasoned library professional answers this question. I put the text of the chapter into a word cloud generator, a visualization tool which increases the size of a word based on its frequency in a list, and the result is Figure 1 (below).

The size of the words “library,” “libraries,” and “librarian,” are unsurprising. This is an LIS textbook, after all. Also unsurprising are the size of the words “people,” “public,” and “users,” given that libraries now tend to focus on the needs and wants of the people that use them. (Of course, as the chapter notes, this was not always the case; imagine waiting anxiously for a copy of Captain Blood only to receive Modern Dairy Management instead.)

Yet what struck me most was the prevalence of the word “sometimes.” Sometimes, a library is and does certain things, and sometimes it is and does something else. As the text notes, “Sometimes…it is easier to say what a library is not.” I’ll admit that at certain times in my life, the “sometimes-ness” of this chapter probably would have irritated me. In my early 20’s, I wanted clear lines and distinct, precise definitions; to organize and categorize was to understand.

A few decades later, though, I think that “sometimes” is the most accurate definition we have of libraries, because to draw the clear line and offer the precise definition would necessarily limit our understanding of an institution that has consistently shown its flexibility, adaptability, and willingness to respond to changing people, changing circumstances, and changing technologies.

Living and working in the gray area of “sometimes” can be frustrating, since it’s understandable to wonder if it’s a library’s responsibility to respond to community challenges from abandoned shopping carts to stocking Narcan to combat the opioid crisis. But I think “sometimes” is also liberating. It frees libraries to define for themselves what they are and what they do. While a pithy, Tweetable definition of “What is a library?” still eludes me, like Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart said in 1964, “I know it when I see it.”

Continuing the Conversation: A Response by Nolan Rochford-Volk, MA, MLIS (Libraries, Culture, and Society, Fall 2024)

Two images that come to mind to describe a library, for me. One is looking from the west side of the river at the eastern half of the downtown district of Waterloo. In this image, you can see some of Waterloo’s most iconic structures—the Black’s Building, which represents a time of opulence and commercial success for the city (positioned below the flag); the Waterloo Industries building (silver, on the right); and the 4th Street Bridge and it’s accompanied pedestrian walk, which lights up at night in rainbow neon.

Downtown Waterloo uploaded to Wikimedia Creative Commons on Sept. 23, 2022.

Funnily enough, we are also looking at the side of the river that receives the most ridicule in the city because behind all those big buildings are the poorest neighborhoods in Waterloo. It is probably the most diverse side of the city, with some of the greatest rates of systemic poverty in the United States. In 2018, The Des Moines Register noted that 24/7 Wall Street “named [Waterloo] the worst city in the country for black Americans, based on wide gaps in income, unemployment and homeownership along racial divides.” As of 2023, this figure has not improved; Waterloo was still ranked “the sixth worst place for Black people to live.” Waterloo is the former home and birthplace of Nikole Hannah-Jones, the Pulitzer-prize winning author of The 1619 Project, a text reframing American history with Black history in mind. In short, we are a community known for its racial divides—something that cannot be bridged by the nine bridges across the Cedar River in Waterloo.

The Waterloo Public Library (WPL), the other image, sits on the west side in the former Post Office building. It’s a gorgeous historic building on the outside, and as I write, it’s in the process of going through a very slow remodel to fix the many wrongs of a ’90s renovation.

WPL as photographed in The Courier.

It is rarely climate controlled; today, with temperatures soaring towards 100 degrees, the A/C tripped off overnight, meaning that I walked into a very warm building this morning. It has cracks in the plaster, and we haven’t had new carpet since before I was born. This is the first library I’ve ever worked in, and it’s only been just over a year since I started at WPL. I work in Reference and Circulation, though my heart really lies in the research with which my Reference department engages. Lacking a great historical society focusing solely on Waterloo, our Reference Department has stepped up to provide patrons with great local history resources and staff who engage the public with local history programming. It is at WPL that I learned what librarianship really means to me. Before, it was just a source for books when I was too poor to afford my own. Now I understand that it is much more than that; it is a community center for so many types of folks, especially those who are housing insecure and who have struggles in the home. Recently, we’ve hosted many folks seeking jobs since the recent lay-offs at John Deere, which has required my department to do quick professional development on job-seeking documents like resumés and cover letters.

The impact of my experience at WPL on my professional interests is immense. When I began at WPL, I fell in love with research, especially regarding local history. There is a tangibility to local history research, especially when much of what we study is recent history. For example, Waterloo–even decades later–still feels the effects of the farming crisis in the 1980s, with gaps still left in the city’s fabric. See, for example, the hulking corpse of Rath Packing on the east-side riverfront, or the office infrastructure created during the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, which has scarred the downtown with large office buildings and parking garages. In the wake of all of this, people are left behind, even generations later. By going to library school, I hope to learn not only how to better my community with knowledge of information literacy, and that a certificate in Special Collections and Archives will enable me to connect my community to the past so that we can see what kind of world could be our future.

Questions for Your Consideration

- Several library terms are used and defined in this chapter. Which ones are new? Which ones are familiar?

- How would you describe what your library does? You might consider the activities of the library where you currently work or one where you would like to work.

- What values or expectations do you bring to library work? How did you develop these ideas about the field?

- What is your library’s history? You might consider either one where you work or one you use for research and reading. How does that history relate to its current operations?

Footnotes

- Eggers, Lolly. A Century of Stories: The History of the Iowa City Public Library, 1896-1997. Iowa City, IA: Iowa City Public Library Friends Foundation, 1997. ↵

- Librarianship Studies & Information Technology. “Five Laws of Library Science,” September 11, 2022. https://www.librarianshipstudies.com/2017/09/five-laws-of-library-science.html ↵

- Orlean, Susan. The Library Book. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018, 60. ↵

- Orlean, 60. ↵

- Orlean, 60. ↵

- Chase, Zoe, Sean Cole, and Stephanie Foo. “The Room of Requirement.” This American Life, December 13, 2018. https://www.thisamericanlife.org/664/the-room-of-requirement ↵

- Battles, Matthew. Library: An Unquiet History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2003. ↵

- Banks, Marcus. “American Libraries Magazine.” American Libraries Magazine, January 24, 2019. https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2017/12/19/ten-reasons-libraries-still-better-than-internet/ ↵

- See, for example, Books, Moms for Liberty (n.d.), https://portal.momsforliberty.org/resources/current-issues/books/ ↵

- “Tentative Program 71st Annual ALA Conference New York City, June 29-July 5.” ALA Bulletin 46, no. 6 (1952): 177–86. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25693717 ↵

- Hillerman, Tony, Ernie Bulow, and Ernest Franklin. Talking Mysteries: A Conversation with Tony Hillerman. Albuquerque: University Of New Mexico Press, 2004, 26. ↵

- Hillerman and Bulow, 26. ↵

- Ross, Catherine, and Mary Chelton. “Readers Advisory: Matching Mood and Material.” Library Journal 126, no. 2 (2001): 52–56. ↵

- Wiegand, Wayne. Main Street Public Library: Community Places and Reading Spaces in the Rural Heartland, 1876-1956. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2011. ↵

- Gregory Leazer, "The Gulf Between Us: Inordinate Maps of Knowledge from the Bibliographers' Guild," Technicalities 45, 3 (May/June 2025), 16.) ↵

"A library in a public or private elementary or secondary school that serves the information needs of its students and the curriculum needs of its teachers and staff, usually managed by a school librarian or media specialist. A school library collection usually contains books, periodicals, and educational media suitable for the grade levels served."

"A library or library system that provides unrestricted access to library resources and services free of charge to all the residents of a given community, district, or geographic region, supported wholly or in part by public funds."

"A service that helps people find needed information."

"A reduced size photographic reproduction of printed information on reel to real film...that can be read with a microform reader/printer."

"A library established and funded by a commercial firm, private association, government agency, nonprofit organization, or special interest group to meet the information needs of its employees, members, or staff in accordance with the organization's mission and goals. The scope of the collection is usually limited to the interests of the host organization."

Online Public Access Catalog. "A computerized database that can be searched in various ways— such as by keyword, author, title, subject, or call number— to find out what resources a library owns."

"A request from a library user for assistance in locating specific information or in using library resources in general, made in person, by telephone, or electronically."

"The process of providing access to materials by creating formal descriptions to represent the materials and then organizing those descriptions through headings that will connect user queries with relevant materials."

Society of American Archivists Dictionary of Archives Terminology

"Publications of the U.S. federal government, including transcripts of hearings and the text of bills, resolutions, statutes, reports, charters, treaties, periodicals (example: Monthly Labor Review), statistics (U.S. Census), etc."

"Procedures and guidelines that are widely accepted because experience and research has demonstrated that they are optimal and efficient means to produce a desired result."

Society of American Archivists Dictionary of Archives Terminology

"Any person who uses the resources and services of a library, not necessarily a registered borrower. Synonymous with user."

"A cohesive collection of noncirculating research materials held together by provenance or by a thematic focus" or "an institution or an administrative unit of a library responsible for managing materials outside the general library collection, including rare books, archives, manuscripts, maps, oral history interviews, and ephemera."

Society of American Archivists Dictionary of Archives Terminology

"Materials that may not be charged to a borrower account except by special arrangement but are usually available for library use only, including reference books, periodical indexes, and sometimes the periodical issues and volumes themselves."

"An individual responsible for oversight of a collection or an exhibition."

Society of American Archivists Dictionary of Archives Terminology

Also known as Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC). "A hierarchical system for classifying books and other library materials by subject, first published in 1876 by the librarian and educator Melvil Dewey, who divided human knowledge into 10 main classes, each of which is divided into 10 divisions, and so on. In Dewey Decimal call numbers, arabic numerals and decimal fractions are used in the class notation (example: 996.9) and an alphanumeric book number is added to subarrange works of the same classification by author and by title and edition (996.9 B3262h)."

Also known as readers' advisory (RA). "Services provided by an experienced public services librarian who specializes in the reading needs of the patrons of a public library. A readers' advisor recommends specific titles and/or authors, based on knowledge of the patron's past reading preferences, and may also compile lists of recommended titles and serve as liaison to other education agencies in the community."