5 Autumn Diesburg

Back is a Way Forward

Born and raised in Thakek, Laos Lakmany Sisourath lost her father at the age of five. Her father, a kicker who kicked food out of the airplanes to soldiers, “died because [his] airplane crashed…while he was dropping his food to the soldiers.” What she knows of this time comes from a photograph of her mother in front of her father’s coffin at his funeral – she herself does not remember him. “I didn’t know nothing about that because I was so little. I didn’t know what die mean, back then. If I don’t see [the picture] I probably don’t remember anything… We are thankful for those American people that helped my Dad back then.” As the oldest girl in her family and the second of six children, four boys and two girls, Lakmany left school after the third grade. She dropped out between the ages of seven to nine years old, to help her mother provide for their family. For three to four months of the year she worked to help surrounding rice farms harvest their crops. Farmers paid her with some of the crop she helped to harvest, however how much the farmers would be willing to give her remained uncertain. “We would go around to people who need help and they would give a couple bags and whatever they give it to you…If they’re generous enough they’ll give me more, if they don’t it depends on how the rice turns out…I have no idea how much they’re going to give to me until that day…Very stressful. If I see the rice that they give it to me little I feel upset, but I cannot say anything…just accept the rice and come home.” In the off season Lakmany bought items from the local market to resell for profit, “I go buy some other people sell their gardening…anything. Vegetable, fish, chicken, pigs… I just go buy $10 [worth] for example…and sell like $10.50, $11.00 to get that profits…If I don’t sell all…I would come home and get that for my family to eat.”

the second of six children, four boys and two girls, Lakmany left school after the third grade. She dropped out between the ages of seven to nine years old, to help her mother provide for their family. For three to four months of the year she worked to help surrounding rice farms harvest their crops. Farmers paid her with some of the crop she helped to harvest, however how much the farmers would be willing to give her remained uncertain. “We would go around to people who need help and they would give a couple bags and whatever they give it to you…If they’re generous enough they’ll give me more, if they don’t it depends on how the rice turns out…I have no idea how much they’re going to give to me until that day…Very stressful. If I see the rice that they give it to me little I feel upset, but I cannot say anything…just accept the rice and come home.” In the off season Lakmany bought items from the local market to resell for profit, “I go buy some other people sell their gardening…anything. Vegetable, fish, chicken, pigs… I just go buy $10 [worth] for example…and sell like $10.50, $11.00 to get that profits…If I don’t sell all…I would come home and get that for my family to eat.”

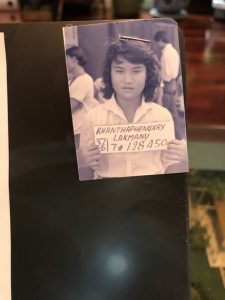

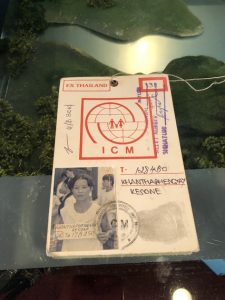

Lakmany’s mother worried over the fates of her children under the Communist government as four of her six children became teenagers. “The Communists would take, if you have four [children] …they would take at least three to be a soldier, like me and my brothers they probably going to take two of us first because yeah, like, 14, 12, 13… My mom afraid that they gonna take us someday…Plus, then, six kid we never gonna be able to live very comfortably over there if we don’t come. We see a lot of people trying to escape…Some people got shot. Some people die from swimming across the Mekong River…So we don’t care. We say we die, die. We survive we get there and we live comfortably, like, over here.” Fears of military child recruitment in combination with their economic struggles pushed her mother to decide they must leave. When the family fled, left in two trips, taking few things with them. Lakmany travelled with neighbors who were also fleeing, a family of three. First, they travelled about an hour from Thakek to another town. They then asked a person with a boat to ferry them across the Mekong River. The boat then parked next to a gardening center located on the river where the group relied on a connection to help disguise them. This connection provided them with uniforms and a basket for the gardening center, so they could blend in with the workers as she awaited her family’s arrival. They waited for two days inside a house, only able to walk up and down the river at night. When her family arrived, the group drove to Napo where each person was given a T number and an NP (Napo) number to identify them as a part of the camp.

The camp itself was “big…a house like a motel…but is not nice like that…has door to door…like row[s]…In that camp is a lot of killing. People have… a knife, a gun. Every day we pray to be alive over there.” Lakmany remembers life in the camp as “poor”: food rations came once a week, stored away until the next distribution, the only clothes available were those they brought from Laos, and the walls were made of glued-together newspapers fitted between bamboo poles. With no school to attend they would eat, sleep, and wait. Nothing but waiting to know where they would go, if they could go. Nothing but waiting. Each week mail arrived, surrounded by talk, often filled with contents impacting everyone in the camp, “Everybody would go ‘what room gonna be so lucky today?’ So always the same room. And then after that they would have money to go out to the market to buy good food…smells so good and oh my god I want to eat…They always have nice clothes. Moneys always come every month for them, you know, but not us. So, very, very sad.”

As neighbors received their interviews, Lakmany wished them luck, waving, and wondering when she and her family would be able to interview – 18 months of wondering passed before they met with an American representative. Lakmany says her father’s work with Air  America expedited their interview process; many in the camp were forced to wait three to four years for an interview. This long interim forced some to choose to return to Laos and others chose to interview with France. Many people did not want to go to France – they wanted to go to the United States. Throughout the camp, interviews were both coveted and feared, “I would see a lot of people walking… ‘Are you nervous for interview today?’ with the [people] waiting to go in…Everybody was nervous because sometimes they fail, they come out and cry. And sometime, they come out happy because they passed the interview.” Leading up to her family’s interview, Lakmany’s mother worked with them all to give the same answers. Interviewers would split up families and then ask them the same questions. These groups were vetted as families by whether or not they gave the same. The reasoning behind this method being, if a group were a family they would, supposedly, know and share the exact same information to questions such as, “How many windows are in your house?” If a group had claimed unrelated people, adding them as family, they would not then provide the same answers about their lives, according to this logic. All of Lakmany and her family’s interview prepping however, became obsolete. “They said [the interviewers] ‘All of you come in!’ Like, ‘oh, good’ not like we heard from other people… So, we all come in and sit at a table…and an American person and a translator sit there and say, ‘Do you wanna come to America?’ …Everybody’s nodding yeah…We don’t know yes… ‘Okay, you come to America with us!’ That’s all they ask…And then we pass…nothing else.”

America expedited their interview process; many in the camp were forced to wait three to four years for an interview. This long interim forced some to choose to return to Laos and others chose to interview with France. Many people did not want to go to France – they wanted to go to the United States. Throughout the camp, interviews were both coveted and feared, “I would see a lot of people walking… ‘Are you nervous for interview today?’ with the [people] waiting to go in…Everybody was nervous because sometimes they fail, they come out and cry. And sometime, they come out happy because they passed the interview.” Leading up to her family’s interview, Lakmany’s mother worked with them all to give the same answers. Interviewers would split up families and then ask them the same questions. These groups were vetted as families by whether or not they gave the same. The reasoning behind this method being, if a group were a family they would, supposedly, know and share the exact same information to questions such as, “How many windows are in your house?” If a group had claimed unrelated people, adding them as family, they would not then provide the same answers about their lives, according to this logic. All of Lakmany and her family’s interview prepping however, became obsolete. “They said [the interviewers] ‘All of you come in!’ Like, ‘oh, good’ not like we heard from other people… So, we all come in and sit at a table…and an American person and a translator sit there and say, ‘Do you wanna come to America?’ …Everybody’s nodding yeah…We don’t know yes… ‘Okay, you come to America with us!’ That’s all they ask…And then we pass…nothing else.”

After the interview, the family remained in the camp for two to three weeks before transferring to a refugee camp in the Philippines. They were slotted to be the Philippines for three to eight months. The new camp hosted people from several different places: Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, but none of them spoke the same languages. The camp split itself into different parts: the Vietnamese part, the Cambodian part, the Laotion part, yet everyone remained able to interact as they wished. This ability to interact freely, while liberating, also posed danger, “Each other don’t like [one another] … You don’t like me I don’t like you…hate crime [happened] a lot over there.” The family remained in the Philippines waiting again, this time to be told their departure date for the United States. When the family received one, they started a countdown. While counting down, activities existed to fill the waiting. Lakmany and her family went to school, “We go to school, just like going to work. On time… Learning to use the stove, the telephone, the refrigerator.  Learn how to traffic… learn… American culture… Plus, you check your health too. If you have TB, you take all the… medicine first to get rid of everything you have… We don’t pass [the medical tests] … so we have to wait eight months. We go to school, while we do that… We could go to like find some bamboo shoots, we could… go play in the stream, river… Not like in Thailand where we can’t go nowhere… Sunday, Saturday after no school… We just go play in the forest jungle. Just like in my country…” Due to the difficulties of finding an apartment for seven people and the medical healing taking place for the family in the Philippines the process took eight months, a longer period than the family expected.

Learn how to traffic… learn… American culture… Plus, you check your health too. If you have TB, you take all the… medicine first to get rid of everything you have… We don’t pass [the medical tests] … so we have to wait eight months. We go to school, while we do that… We could go to like find some bamboo shoots, we could… go play in the stream, river… Not like in Thailand where we can’t go nowhere… Sunday, Saturday after no school… We just go play in the forest jungle. Just like in my country…” Due to the difficulties of finding an apartment for seven people and the medical healing taking place for the family in the Philippines the process took eight months, a longer period than the family expected.

Lakmany and her family spent about two and a half years in transition from the time they fled Laos to the time they arrived in Iowa. Barbara Davidson coordinated three Iowa churches to sponsor them with the support of social worker Bev Weissman. These women  prepared for the family’s arrival by finding them an apartment with schools nearby. When first arriving in Iowa the family’s head sponsor, Barbara Davidson, asked the person who lived below their new apartment to greet them at the airport. On hearing Lao people talking, Lakmany says, “I was so happy! I was like, oh, we’re not alone…When we came home knowing they lived downstairs we felt very safe…She [Barbara Davidson] already had rice, whatever Lao people eat in the cupboards because of the people that lived downstairs…We saw a lot of clothes… Whoa a lot of clothing…Very happy the first time we see home…but it’s cold.’” Lakmany found adjusting difficult because of her shyness, especially when the churches sponsoring the family ferried them to a different church every Sunday. She didn’t speak much English and didn’t know what they were doing in church, but she knew, no matter how much she didn’t want to go, parishes needed to see her and her family since they sponsored them. Lakmany’s memories of this transition will remain forever soaked by stress, especially surrounding the difficulty of learning English. Lakmany went from not attending formal schooling since the third grade to being put into high school under a new school system with a new language. Tutors came each night to help with homework, sometimes Barbara, sometimes Bev, sometimes her daughter Amy.

prepared for the family’s arrival by finding them an apartment with schools nearby. When first arriving in Iowa the family’s head sponsor, Barbara Davidson, asked the person who lived below their new apartment to greet them at the airport. On hearing Lao people talking, Lakmany says, “I was so happy! I was like, oh, we’re not alone…When we came home knowing they lived downstairs we felt very safe…She [Barbara Davidson] already had rice, whatever Lao people eat in the cupboards because of the people that lived downstairs…We saw a lot of clothes… Whoa a lot of clothing…Very happy the first time we see home…but it’s cold.’” Lakmany found adjusting difficult because of her shyness, especially when the churches sponsoring the family ferried them to a different church every Sunday. She didn’t speak much English and didn’t know what they were doing in church, but she knew, no matter how much she didn’t want to go, parishes needed to see her and her family since they sponsored them. Lakmany’s memories of this transition will remain forever soaked by stress, especially surrounding the difficulty of learning English. Lakmany went from not attending formal schooling since the third grade to being put into high school under a new school system with a new language. Tutors came each night to help with homework, sometimes Barbara, sometimes Bev, sometimes her daughter Amy.

Lakmany felt most comfortable again when she married in 1990. “Again, I am a head of household…Me and my sponsor learn how to write check, learn how to pay a bill, learn how to… go to food stamps, learn how to interview.” Lakmany has been living in Iowa since 1986. After finishing high school in 1990 she worked at P&G from 1995-2018. For a year, she has been working as a custodian at the University of Iowa. “I am very happy now, I will say we are success now…So, my life right now is pretty good because I’ve been working hard…We bought a house together…We pay off long time ago…My son, my daughter is grown up and being pretty good kids…The house over there is our rental… and my mom lives next to the rental…so she can be close to us. I am so happy with my life now compared to when I was in Laos.” Now, Lakmany is focused on retirement and going at her own pace. Recently, a neighbor from Laos told her what happened to her family’s home and their belongings when they fled. Neighbors came the next day, grabbing whatever they could. Her mother’s close family got the house and the land after fighting and paying the government for it. “I don’t…miss my things because I came here and I got good life…even my land and my house my Dad built before he died for my mom’s family…The house…looks huge when you’re little…but when I went home last year, two years or something the house is so small…I’m shrinking or the house shrinking?” When she retires, Lakmany would like to return to her childhood home to know what life is like there. Her mother, protective of her children, would not allow them to go to out or to go to celebrations when they were young. She would like to know when things are celebrated and to experience the cycle of a year in Laos. “When I retire, I want to go to see what life in whole year look like…I want to see and come back.”

***

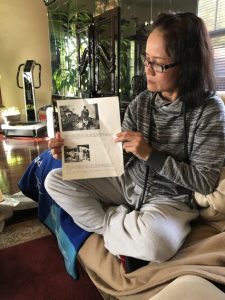

As I parked my car in front of her house for the interview, Lakmany stood on the front step of her two-story home, holding her glass outer door open to greet and usher me in. She led me through a split foyer, past her kitchen, and up a small flight of stairs into a large living space furnished with beautiful glass cases full of art. In one half of the room sat ornate red and yellow silk furniture trimmed with black wood. We turned to the other half to sit on a soft, brown couch with seats sculpted from use with blankets resting on its corner in a pile, waiting for Lakmany’s daily nap. She tucked her feet beneath her knees, adjusting. We sat together as bits and pieces of memory floated through the air, begging to be caught and examined.

***

From a young age Lakmany worked to help her mother provide for their family. As she spoke of her youth, it became clear that the role of a provider has become a central part of how she identifies herself. When Lakmany speaks of her brothers and sister there is a quality of both siblinghood and caretaker in her memories. Despite the responsibilities she undertook as a young person, her role as a co-provider does not seem to have prematurely aged her out of her childhood – she remembers feeling little, a child looking up to her mother, in awe, for guidance. Providing became so engrained in her she did not feel comfortable during her transition to the United States until she again found herself in the role of a caretaker, learning to write checks, pay bills, and interview for jobs. Taking care of the practical matters of a household became the strongest balm for her healing through the transition. In the adjustment, many of the variables of her life became unknowns – she didn’t know anyone but her family, she didn’t know the school system when being placed in high school after missing several grades, she didn’t know the language, or the landscape, or the culture – but what she did know was how to take care of her family. By learning practical ways to run a household she found a familiar place to start and grow from.

aged her out of her childhood – she remembers feeling little, a child looking up to her mother, in awe, for guidance. Providing became so engrained in her she did not feel comfortable during her transition to the United States until she again found herself in the role of a caretaker, learning to write checks, pay bills, and interview for jobs. Taking care of the practical matters of a household became the strongest balm for her healing through the transition. In the adjustment, many of the variables of her life became unknowns – she didn’t know anyone but her family, she didn’t know the school system when being placed in high school after missing several grades, she didn’t know the language, or the landscape, or the culture – but what she did know was how to take care of her family. By learning practical ways to run a household she found a familiar place to start and grow from.

Among the common themes of the refugee narratives shared with, and studied in, the class and the fine-print, definitional trends of the refugee regime, Lakmany’s connections did create a unique situation for her family. Her father’s work on airplanes transporting supplies for Air America helped to expedite her family’s interview and processing. Although her family’s situation is exceptional in this aspect there are several parts of their refugee experiences which seem to resonate within many of the refugee narratives the class has been privileged to hear over the course of the semester. In her interview, Lakmany discusses how her family fled Laos for multiple reasons: for fear of military child recruitment and for fear of the impacts of economic instability on their livelihoods.

Lakmany’s experiences illustrate how, often times, being forced to migrate is influenced by several different factors. Her experience shows how important it is to understand how complex forced migration can be and how important it is to include refugee narratives in all their fullness in the discussions concerning the definition of a refugee.

Today, Lakmany experiences home as a duality with Laos maintaining a prevalent space in her life and mind. Though she only had the opportunity to live in Laos for 14 or so years it remains home. As a child, Lakmany’s mother did not allow her to experience much of Laos as a measure of protection, one which she believes kept her and her siblings safe, but she would like to get to know Laos in a way unallowed to her before. It is not her physical childhood home drawing her back, but the culture of her home. She wants to understand more of where she came from, to see celebrations, to see harvests, and to see the cycle of a year in Laos. Lakmany wants to go back to experience what she has been unable to, but after, she wants to come back here to Iowa. The blurring of back – back to Laos, back to Iowa, back to memories, back, back, back. Maybe back is a way forward.