4 Hartley Christensen

Narrative Summary

Sunday Goshit: a Story of Immigration and Greater Hope

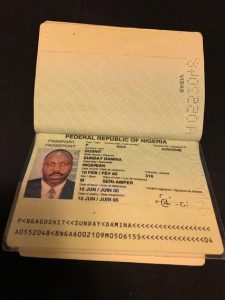

Sunday Goshit, originally from Nigeria, immigrated to the United States of America in August 2000 when he was forty years old and has remained in Iowa for the past 19 years on a student visa. After a year in the United States by himself, he was joined by his wife and four children who were fleeing dangerous conflict in their once peaceful community. Sunday spent the majority of his life in Nigeria, which he describes through the framework of his schooling. Sunday’s smile remains just as big as he narrates his graduation from elementary school to when he talks about earning his second college degree. Education has guided Sunday throughout his whole life and is the single factor that allowed him to immigrate to the United States. Even though Sunday has finished his formal education, he continues to view himself as a student in life; he habitually takes the time to reflect on all his experiences past and present and what they have taught him about family, work, and maintaining happiness.

When asked about his favorite memory from Nigeria, Sunday emphasized his relationship with his family and the community around him. Sunday was raised by his uncle after his father’s death when he was only three years old. Sunday quickly learned how to share amongst the 16 other children also being raised in that home and within his broader community. Sunday encompasses his cousins, friends, and neighbors into whom he believes are his “brothers and sisters.” In Nigeria, Sunday’s family and all his neighbors left their doors unlocked for each other to come in, eat, and visit freely on any given day which garnered a strong community bond throughout his childhood and into his adult life. Sunday explains that during his adolescence Nigeria was thriving as a larger society as well, disabling him from the idea of permanently leaving his family or country. If he thought about life or education outside of Nigeria, he never imagined himself permanently leaving but rather using study abroad programs as an opportunity for travel.

When Sunday was well into his adult life and career in Nigeria as a high school physical geography teacher, a group of professors from the University of Iowa visited his high school to learn about how to correctly teach the geography of Africa in America schools. The director of the Global Studies Program was impressed with Sunday’s teaching and research methods and asked him if he would consider coming to the University of Iowa to complete his PhD. Sunday believed this opportunity wouldn’t extend beyond a year and so he graciously accepted the offer.

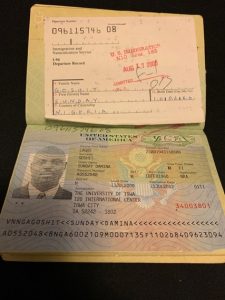

Sunday entered the immigration process without any previous knowledge about the immigration services provided by the United States. Sunday conjectures that this is because of his uncontended desire to stay in Nigeria. When we began to further dissect his knowledge about the vetting process in the United States, Sunday brought up his recognition of lottery visas and their initiatives to allow people from underrepresented states to migrate to the United States. He remembers being given an application for a lottery visa during his teenage years but never completed it for a lack of incentive to leave Nigeria. Entering a stage in his adult life where traveling abroad to study held numerous social and economic benefits for his family, he applied to the University of Iowa. Upon his acceptance, Sunday received a document called an I-20 which is a document from the  University of Iowa that gave him access to resources at the United States Embassy in Nigeria to help him begin his application for a student visa. After filing his application for a student visa, Sunday underwent numerous interviews with the embassy. The embassy wanted to establish any familial connections Sunday had within the United States, his background, and his intentions in applying for a student visa. Although Sunday was to be granted a one-year student visa from the embassy, what he remembers most from the interviews and his vetting process was the feeling that the United States did not ever want to house him permanently and that his schooling would be temporary.

University of Iowa that gave him access to resources at the United States Embassy in Nigeria to help him begin his application for a student visa. After filing his application for a student visa, Sunday underwent numerous interviews with the embassy. The embassy wanted to establish any familial connections Sunday had within the United States, his background, and his intentions in applying for a student visa. Although Sunday was to be granted a one-year student visa from the embassy, what he remembers most from the interviews and his vetting process was the feeling that the United States did not ever want to house him permanently and that his schooling would be temporary.

Sunday believed that the whole idea of coming to the United States relied heavily on the notion of it being a developed country. Much to his surprise, Iowa was nothing like Hollywood’s glamorous mainstreamed depictions of LA and New York. Sunday searched for skyscrapers, forests, mansions or even military personnel rushing around the streets with their guns in tow from the window of his seat on the airplane as his flight landed at the Cedar Rapids airport. Much to his disappointment, the window only offered views of flat farmland. Sunday thought that his cultural shock would rise out of his proximity to overly lavish lifestyles or a far greater ease of life, but he instead found himself confused with how much smaller his life got. Sunday came from a bustling city in Nigeria of over one million people and an extensive family and community to a place with only 60 thousand people with very few connections to the land or people. Though Sunday finds this shock humorous now in hindsight, it was just the beginning of his struggles upon arriving in the United States.

For the first year that Sunday was living in the United States, he was having to navigate an entire new culture within Iowa by himself as well as deal with the personal trauma of being separated from his family. His anxieties reached an all time high on September 7, 2001 when a major religious crisis between Christians and Muslims began to endanger his wife and children back in Nigeria. Hundreds of people died in the town that his family resided in, and he was often unable to reach them during these highly tense moments. Following this crisis was the terrorist attacks on September 11th in the United States, which further  jeopardized his family’s chances to leave Nigeria and seek asylum in the United States. Luckily, his family was accepted into the US under Sunday’s student visa. Some of the resources Sunday found most imperative to his transition in Iowa were: his host family in West Liberty where he would spend weekends, his academic advisor and other resources from the University of Iowa, his church family, and the African Community Association. All of these resources helped make settling down easier for Sunday and alleviated some of the pressures from social isolation, language barriers, and discomfort in navigating the city.

jeopardized his family’s chances to leave Nigeria and seek asylum in the United States. Luckily, his family was accepted into the US under Sunday’s student visa. Some of the resources Sunday found most imperative to his transition in Iowa were: his host family in West Liberty where he would spend weekends, his academic advisor and other resources from the University of Iowa, his church family, and the African Community Association. All of these resources helped make settling down easier for Sunday and alleviated some of the pressures from social isolation, language barriers, and discomfort in navigating the city.

After being a teacher’s assistant at the University of Iowa for nine years, taking community courses at Kirkwood, attaining a degree in Information Technologies and getting his PhD from the University of Iowa in Geography, Sunday was still unable to meet the qualifications of the American job market due to the status of his visa. Sunday explained a stipulation in applying for work with his visa: his employers had to ensure that there was no qualified American citizen that could also fill that position. Even when Sunday proved to be a more qualified and agreeable candidate for a position, jobs turned him down after he mentioned his visa and the extra work the company would have to do to secure his employment authorization or green card. Although he was not able to use his degrees to the extent he thought he would be able to, Sunday still found a way to make the best of his opportunities. With a necessity for income, Sunday became a caretaker for a small handful of mentally and physically impaired people, a position that he has great pride in maintaining today. Although this job was not what Sunday hoped he would be doing, he feels very grateful for all the lessons his patients have taught him. He values his patient’s honesty and frankness that he feels lacks in a lot of people he interacts with outside of his work.

Sunday’s visa has been expired since 2001, but he still holds a legal status as a student through his continued studies at Kirkwood Community College. If Sunday ever wanted to leave the United States for travel and come back, he would have to apply at a US embassy for a new visa. Sunday acknowledges that the vetting process is much more tedious and vigorous towards immigrants coming to the United States today than it was when he was given his student visa. Sunday does not see himself leaving the country for those reasons. All four of Sunday’s children have graduated in American schools themselves and have found careers and spouses within the United States. With the arrival of grandchildren Sunday and his wife have begun the process of attaining green cards earlier this year, but the process has become a very costly endeavor. Sunday and his wife are currently paying international fees covering his student visa, lawyers to help them apply for permanent residence, as well as sending money to people back home in Nigeria. When all of these fees are compounded together, they amount to around $7000. Sunday explains that he and his wife expect to attain permanent residence status by the end of next year, as applying as parents of legal citizens (his children are citizens through their marriages to natural born American citizens) is a much easier process than even that process of a spouse. He hopes that attaining a green card will make getting back into teaching and professional research at the University of Iowa or through the government much easier.

Concluding the interview, Sunday wanted to make a final note to our class; he first emphasizes that everyone who comes to the United States comes with a different experience and secondly that it is important to hear those experiences. Sunday expresses his glee that our class is under the tutelage of Professor Weismann in seeking out those stories and trying to understand the history and people behind them.

Personal Reflection

Interviewing Sunday was not only my first formal interview process but my first experience navigating a personal story of an immigrant. This was a challenge for me as I tried to follow the structure of attaining pieces of his story before, during, and after his migration to the United States while also giving Sunday the space to tell his story the way he wanted it to be heard. I felt that giving the reigns over to Sunday to steer the interview would ease my fears of pushing information out of him that he was not ready or willing to share. The lack of formality within the structure of the interview allowed for my interaction with Sunday to mirror that of a conversation between equals. I found that the conversational component of our interview actually made Sunday more willing to share personal anecdotes and opinions alongside his historical knowledge of conflicts in Nigeria. Although our class focus has been on the experiences of refugees, I have found many parallels between the experiences of a refugee and that of an immigrant through my experiences with our guest speakers in class and my conversation with Sunday.

Although I did not expect to learn about the religious and ethnic landscape of Nigeria, Sunday gave me the most extensive history lesson I have ever been privileged to hear. Sunday and I talked about him being raised in a region that fell in the middle of his state where there was tolerance of religious and ethnic difference to his South and much less tolerance of that to his North. For these reasons, Sunday always felt the push and pull of the conflict. Learning about the nature of the social political system in Nigeria and how it allowed Sunday to see the value in allowing others the right to express themselves freely really allowed me to build upon our class discussion about the power of diversity. Not only was Sunday able to learn about and respect a religion outside of his own but he was able to build familial relationships with those people allowing for a prosperous and peaceful neighborhood and community. This idea of understanding other people’s diverse experiences and identities and how that diversity enriches our way of life is an important lesson. How we structure policy affects how people of different backgrounds can interact and can inhibit a greater quality of life for everyone.

Another significant fact that revealed itself in our conversation was the evolution of the United State’s vetting process. Sunday talked about the ease of his experience in applying for a student visa in the late 90s being due to the nature of our international interactions. The United States was not vigorously vetting immigrants to weed out terrorists when Sunday applied for a visa as they so extensively do today. The terrorists attacks on 9/11 play a major role in this change in policy concerning the vetting process of immigrants and refugees, but as we have also learned in class there are a lot of underlying national interests to remain sovereign that restrict a nation’s willingness to uphold their international responsibilities to take in immigrants and refugees. This was an important point to bring up in our conversation because it reflects how our policies and institutions are guided by our social and political landscapes. More importantly, those landscapes are not set in stone and can once again evolve. Although a more intense vetting process is necessary for national security today, the quality of care and empathy extended to individuals in those processes needs to be held at a higher standard.

The most significant article of information I learned from Sunday was the necessity of a positive mindset. This was also present in the presentation of our guest speakers such as Amir Hadzic, Dukan Diew, and Matsalyn Brown. Like the refugees our class has studied, Sunday seemed to employ an unconditional positive regard for life with ease, even when talking about the most dire of circumstances he has found himself positioned in. Sunday endured an entire year of isolation from his family where he questioned their health and safety so vehemently that it took a toll on his schooling. Sunday is also a man who has dedicated his entire life to studying and teaching others about our natural world, but he has been denied the opportunity to continue those studies in a professional setting because of the status of his visa. Despite being rob of this opportunity, Sunday views his work with the mentally and physically impaired as his dream job. Sunday explains that the idea of the American dream is so malleable to him and that as long as he is able to provide for his family, he can make any job his dream job. This untested positive mindset that Sunday expressed stuck most with me from my conversation. It reminded me that no matter the adversity of my circumstance, there is always an alternative perspective to view it through. My life has not been afflicted by the status of my citizenship, the isolation of family, or violent conflict in my state, and yet I don’t seem to hold nearly half as much of the resilient nature that seems to govern every action and spirt of Sunday. Sunday has taught me so much about the history of Nigeria and the experiences of immigrants in the United States, but he has especially reminded me of the spirt of the human condition and its ability to overcome any obstacle.