18 Jenna Riordan

Narrative Summary

Sarajevo, the capital city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, is infamous by many for being the site of a deadly siege lasting more than three years during the Bosnian crisis. For Amir Hadzic, Sarajevo means much more. Raised by two parents in an apartment with his older brother, Amir experienced Sarajevo before it had been touched by war. Amir describes the pre-conflict Sarajevo as almost idyllic: multiethnic and multireligious yet cohesive and peaceful. Bosnia’s population was 43% Muslim, 30% Orthodox Christians and 27% Catholic, yet,  within the 650,000 population of Sarajevo, 65% of marriages were of mixed ethnicities, pointing again to the unified nature of the Sarajevo population. Amir recalled the feeling of walking down the street, able to hear the bells from a Cathedral, imam singing and sounds from a synagogue all in the same area.

within the 650,000 population of Sarajevo, 65% of marriages were of mixed ethnicities, pointing again to the unified nature of the Sarajevo population. Amir recalled the feeling of walking down the street, able to hear the bells from a Cathedral, imam singing and sounds from a synagogue all in the same area.

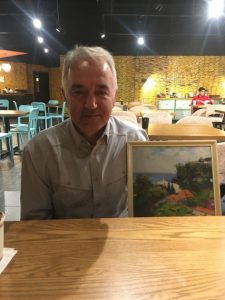

Adding to the idyllic feel of Sarajevo pre-conflict, Amir also brought with him a painting of a vacation home on the coast of the Adriatic Sea, a part of which his family would rent out for family holiday. As Bosnia can get very cold in the winter, Amir’s family would travel to the coast and spend time together, boating and relaxing in the warmth. They would also typically take a month in the summer to stay in the vacation home. Amir spoke very fondly of these times before the violence and before he was forced to flee his home and his family.

In addition to the cohesive nature of the city, Sarajevo was also the host of the Winter Olympic Games in 1984. Having learned English through frequent visits to the American library in Sarajevo, this came with the opportunity for Amir to work with the US Ski Team as a translator for the American athletes. Being such an extraordinary experience, the ability to work with the US team held great significance for Amir; he was even given a ski jacket and hockey stick by the US team.

Amir went on to become an athlete himself, in addition to studying Economics at the University of Sarajevo. Eventually, Amir was offered a contract with a professional soccer team and was able to secure a spot as a professional athlete. However, while life in Bosnia was boding well for Amir, conflict was brewing. After the fall of Yugoslavia, republics began asserting their independence, some of which on ethnic bases. Serbia and Croatia, for example, each gained their independence, with Serbia mainly populated by Serbs and Croatia mainly populated by Croats. Bosnia posed an issue for this kind of homogenic based division, possessing more of a melting pot of ethnicities and religions. In the scramble to obtain territory, the careful balance of power collapsed. With the former Yugoslav army under Serb control, and Serb forces advocating for the ethnic-based division of Yugoslav territory, they began the process of ethnically cleansing non-Serb populations from Bosnia.

Yet, the conflict did not truly hit home for Amir until he had his first run in with such forces. Riding home from playing pool with some friends, Amir’s trolley was stopped by men in uniform who first beat the driver and then instructed all passengers to return to ‘their side’ of the city. Confused about what this could mean, Amir returned home to inform his family about the event. The confusion spread to his parents and brother, as Sarajevo was meant to be a city that embraced differences, not an area where of enforced homogeneity. However, within the next few days, barriers were constructed, dividing the city between east and west. While civilians initially revolted, with over 100,000 Bosnians smashing the barricades the next day, the barrier was reconstructed just two weeks later. Next time civilians attempted to tear it down, they were shot.

Realizing the reality of the situation, Amir and his family switched their focus to survival. In the beginning of the siege, the electricity was sporadically cut, leaving citizens to find ways to survive without amenities that had become a habitual part of their existence. For the first few months, the Hadzic family subsisted on what they had in their home as well as items they shared with their neighbors. However, winter was soon coming, and people began to worry about their ability to survive. Individuals burned furniture in their homes for heat, stripping down their belongings until nothing but necessities remained. Amir returned home one night to find his hockey stick gone, his family forced to burn it in order to survive the cold. Amir, himself, would collect rainwater from the roof of his apartment building in order to flush the toilets and bathe themselves. When this was not possible, people had to face the dangers of violence outside of their homes to walk five miles to the line for water.

During this time, Amir and the rest of the soccer team were put in charge of equipping local hospitals with necessary supplies. It was on one of these supply trips that Amir was convinced of his need to flee Bosnia. While dropping off medications at a local hospital, Amir stopped for a second to chat with a neighbor, but he felt uncomfortable and decided to enter the building. Less than a few minutes later, there was a nearby explosion that collapsed the building and injured some. Luckily, Amir was not substantially harmed and was able to assist one of the doctors in gathering the injured and covering the dead with sheets. Outside, he was met with the unfortunate reality that his neighbor with whom he had been speaking was dead.

In addition, the third winter of the war was approaching, and Amir knew that he would be unable to return to a life of normalcy living in Sarajevo. Amir packed his belonging in two bags, and made his way to the UN controlled airport, under which a tunnel had been dug to assist those fleeing Sarajevo. Because the airport was under UN control, the Serbs were not allowed to bomb the area, which allowed refugees to escape with a smaller probability of experiencing a violent attack. The half-mile tunnel was the only way in or out of Sarajevo. After making his way through the tunnel, Amir had to trek to the top of the mountains surrounding the city, where busses waited to take those who could pay their fee out of the country.

Amir’s first destination was a city in Croatia, where a friend had been staying. Amir spent two weeks there until eventually his friend was relocated to Norway to join his family, who had been resettled before him. Faced with the need to find a new place of residence, Amir went to the Pula Refugee Camp, also in Croatia, run out of the old military barracks of Yugoslavia. Conditions in the camp were unfavorable, as five families resided in a room the size of a classroom. The camp also housed refugees of all ethnicities, which resulted in conflict as each group blamed the next for the events of the war. Having already endured the realities of war and now forced to live in such discouraging conditions, many also turned to drugs and alcohol.

In an attempt to spend at least a small amount of time outside of the camp, Amir approached the Croatian national soccer team, asking the coach if he could simply practice with the team for a few hours a day. However, after a few weeks of practicing with the team, the coach saw potential in Amir and offered him a professional contract. Amir eagerly agreed to play with the Croatian national team so long as they provide him with housing outside the refugee camp and enough money to enable him to send funds back to his family in Sarajevo. In addition to continuing his soccer career, Amir also met Amy, a worker in the refugee camp from the United States. Both having an interest in assisting the children in the camp, they set up a program in which the kids could play soccer, which greatly assisted in the kids learning disciplinary traits as well as how to work as a team. Amy coordinated with sponsors in the United States to provide the children with jerseys and the team was eventually even asked to play games in Italy and other countries. Thus, while life was not easy in Croatia, Amir was able to participate in fulfilling experiences, such as the national soccer team and the youth team he helped to coordinate.

However, towards the end of the Bosnian war and with the massive influx of refugees Croatia had received, the Croatian government was eager to end the war in Bosnia. Thus, it began to mobilize and recruit individuals to assist in efforts to end the war. Having lived in a war setting for long enough, Amir decided he was unwilling to be a part of another period of conflict, and applied for resettlement. Knowing he was open to a distant move, Amir considered relocation to Australia, New Zealand or Canada, yet these programs were rather small with substantially long wait lists. The United States, on the other hand, had just opened its program for Bosnian resettlement that year, in 1995, and Amir decided to apply for resettlement to the US. Through this process, Amir travelled to the Croatian capital many times for interviews. He had to prove that he could corroborate his stories and convince the US that he was not a war criminal and did not participate in any crimes against humanity. He also had to establish that it would be unsafe for him to return to Bosnia. At this time, it was necessary for refugees to have a sponsor in the United States to ensure they would not become a burden on the state. Luckily, Amir had a cousin in Queens, New York City, who was able to sponsor him. The resettlement application process lasted around 8-9 months. Amir then went through a cultural orientation, where volunteers from the US came to educate refugees on what to expect from life in the United States. Then, the refugees for resettlement in the United States were contacted by IOM, who coordinate flights for refugees to their country of resettlement. The refugees were told to meet in a corner of a parking, taken to an airport and Amir boarded a flight to New York City.

After a few weeks adjusting to New York City, Amir was contacted by Amy’s mom, informing him that she would be coming home soon and wondering if he would be willing to come visit her in Iowa City. Eager to see Amy, Amir flew to Chicago and drove to Iowa City, where he planned to spend a few days visiting with Amy and her family. While looking through a newspaper on his visit, Amir happened across a job posting for a part time soccer coach at Mount Mercy University. Having thought that soccer wasn’t very popular in the US, Amir was delighted to find the opening and secured an interview. While Amir did not posses a resume, he had brought with him from Bosnia his scrapbook with details of all 500 soccer games he had played in his career as well as a pair of cleats. Fortunately, this was enough to help him score the job and Amir made the move to Iowa City. Amir is now the head soccer coach for the Mount Mercy men’s soccer team as well as a coach for the Xavier high school soccer team.

As for his experience in the United States, Amir now feels at home in the States. Amir related the story of his parents to me: his mother having died of heart issues that had been exacerbating by living in a war-torn city for so long. His father passed just two years later from an aneurism, after having expressed his desire to join his wife of over fifty years for some time. Unable to be there for his father’s death, Amir flew to Bosnia to plan the funeral and described to me the uncertainty he had about how he would feel once he flew back to the United States, no longer having close, concrete ties to Bosnia. Amir shared that touching down in Iowa City after the death of his father was the first time he felt at home in the US and just a few short days later, he decided it was time that he marry Amy, as there was no longer a feeling of uncertainty over whether he would someday move home to be with his family.

While they were together, Amy had the honor of working in the Hague, where war criminals are tried. When Amir was in the Netherlands visiting Amy, she surprised him with tickets to the trial of the Serbian President who was responsible for a good deal of the war crimes committed in Bosnia. The roundabout path of Amir’s life as a refugee came full circle in his being able to witness the man who was responsible for the conflict that disrupted his life be tried in a criminal court.

Personal Reflection

Of the information Amir supplied me with, there were some key points that stuck with me. For one, his brother’s migratory experience was much different than his own. When first discussing Amir’s experience fleeing Sarajevo, he touched on the fact that he had a brother but did not expand on what came to be of him. As I brought his brother up further into our discussion, Amir described how his brother had had a family in Sarajevo, a wife and a son, who had fled the conflict. His brother didn’t end up leaving Sarajevo until 1996/1997 and eventually divorced his wife. He reached out to Amir and asked if he could come live with him in Iowa, to which Amir agreed and his brother came to join him in the States. However. Amir’s brother’s experience differed greatly from his own. Back in Bosnia, his brother had been a civil engineer, but in the United States, he would have had to take a test and possibly pursue further training to be employed in a similar job, a task which he never felt the motivation to complete. Amir’s brother remained in the United States long enough to gain dual citizenship, but then after five or six years, moved to Croatia, where he opened an engineering firm and performs musically as restaurants and bars on occasion. This story was significant for me because of how the two had come from the same family and yet have two very different stories to tell. In class, we heard many tales of the difficulties in transferring degrees and qualifications from countries of origin to the United States, yet it was interesting to see how Amir could apply his knowledge of the game of soccer in the States, while his brother’s civil engineering skills did not transfer. This story for me just goes to show how one or two differences in the lives of refugees can make a big difference in adaptation and assimilation to a country of resettlement.

A big part of Amir’s migratory experience, and his life in general, is the game of soccer. In Bosnia, Amir played the sport growing up and was eventually made a member of a professional team. When he was forced to flee his home, two things he made sure to pack and bring with him were his soccer cleats and his scrapbook of all of the games he had played. Then, when things became difficult to deal with in the refugee camp, Amir again turned to the sport, and was even signed to a professional team in Croatia. When he was applying for resettlement in the United States, he was given the opportunity to fly out of Croatia in April, but he decided that he wanted to finish out his last season and chose instead not to resettle until July, rounding out his soccer career at exactly 500 games. Even in resettling, Amir jumped at the chance to again be a part of the sport in applying for a coaching position at Mount Mercy. As soccer is such a relevant part of Amir’s life, it was also very relevant to our conversation. Being from Iowa, my hometown boys’ soccer team played Xavier in the state tournament many times. Amir and I got to talking, and we realized that he had coached the team that battled my brother’s team in the state tournament. Amir even told me that he had to alter his strategy around my brother a time or two. While this was interesting in itself, I thought Amir’s journey with soccer was even more relevant. It can be difficult for refugees to assimilate in their country of resettlement, and I am sure it was not easy for Amir either. Yet, Amir had something that some don’t: a different kind of language in the form of building connections through soccer. I think soccer played a big role in Amir’s ability to find his place, as well as cope with difficulties, in his home country, his host country and his resettlement country.

The story that stuck with me the most was what Amir related to me as his answer to my question, is there a specific memory you associate with the time you began to feel at home in the United States? Unsure of what I was expecting, Amir told me the story of his parents’ passing. Amir’s mother had had heart issues for a good portion of her life, and as the conflict piled on more stress, her life was shortened, and she passed due to a heart complication. Amir’s parents had been married for more than fifty years and had always been very close. Because of this, his dad expressed his desire to be close to her as soon as possible and he, himself passed two years later due to an aneurism in his stomach. Amir intended on visiting his father that December for Christmas, but received a call from a cousin that his dad was not doing well and considered moving his trip up. Yet, the doctors told Amir that it would be better for him to come stay with his father after the planned surgery anyway, as he would need more assistance in recovery. Unfortunately, the day after his father’s surgery, he passed. Amir took a flight to Bosnia to coordinate funeral plans, but when he came back, he recalled that he finally felt like he could call Iowa his home. He related that he never knew, until his parents died, what his future would look like: if he would return home, if they would relocate, etc. When those ties were severed and Amir reviewed his life in the States, he knew that he was home. This was significant information for me, as I did not know what he would respond to my question. I didn’t know if starting a life with Amy would be his response, or possibly settling in at a new job. Amir told me that it is necessary for people to understand that refugees do not choose to leave their home countries and I think that fits in well with this story. Amir’s parents did not want to leave Bosnia and so they decided to stay and face serious danger while their two children fled. Yet, a few pieces of Amir stayed behind: his parents and the memories of his childhood. While memories can be made other places, family is irreplaceable and so it makes sense to me that Amir was finally able to call his country of resettlement his home only after he had no immediate family back in Sarajevo.

My experience interviewing Amir Hadzic was as equally informative as it was rewarding. Amir was open to discussing with me his experiences before, during and after his migration. I was fortunate to be paired with Amir for this project and he will be someone I remember fondly and hopefully keep in touch with for as long as possible.