Families are one of our biggest socializing influences. Families teach us the rules, norms, and customs of our culture. Social learning theory argues that these “lessons” impact our values, attitudes, behaviors, and communication well into adulthood (Arnett, 2000; Bandura & Walters, 1963). Further, our family-of-origin influences our thinking about intimate relationships, including romantic bonds and sexual relationships (O’Sullivan et al., 2001). In this chapter, we’re going to discuss a few family factors that influence sexual behavior and look at how family communication can enhance (or hinder) our sexual well-being and satisfaction.

Family Factors: Attachment Theory

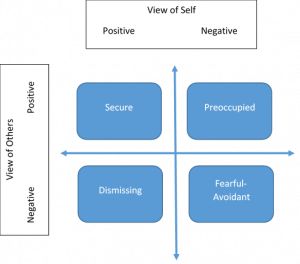

For decades, Attachment Theory (Bartholomew, 1999; Hazen & Shaver, 1987) has been used by social scientists to explain how our bonds with our primary caregiver(s) serve as a “blueprint” for future relational functioning. Based on experiences with primary caregivers, individuals develop “internal working models” about how they view themselves and how they view others (Bartholomew, 1990). Our perceptions of self and others range can be placed on a continuum from positive to negative. The intersection of working models or self and others results in our attachment styles:

Figure 1. Bartholomew’s (1990) Four Attachment Styles

Individuals with a secure attachment have a positive view of both self and others. They are typically comfortable being close to others and feel that they can trust others. Secures value relationships, but also are comfortable being independent and on their own.

An individual with a preoccupied attachment style have a negative view of self, but a positive view of others. These folks want to be close to others and often have an “insatiable desire to gain others’ approval” (Bartholomew, 1990, p. 163). Further, preoccupieds’ negative view of self makes them doubt that others want to be with them. As a result, they may be overly dependent or “clingy.”

Someone with a dismissive style has a positive view of self, but negative view of others. They tend to view others as untrustworthy or unreliable. Dismissives do not shun close relationships, but they also don’t seek them out. Dismissives tend to favor autonomy over connection with others.

Finally, individuals with a fearful attachment style have negative views of themselves and others, resulting in a lack of trust and avoidance of close ties due to a fear of intimacy.

Attachment styles influence our behaviors in family relationships, friendships, and romantic partnerships, including our sexual relationships.

For instance, Barnett et al. (2018) found that individuals who are preoccupied (want to gain approval and can be “clingy”) had more interest in ensuring their partner orgasms, whereas individuals with fearful attachments had lower interest in partner orgasm. The researchers argue that preoccupieds concern about relational rejection likely motivates their interest in partner orgasm, but fearfully attached individuals fear of intimacy may preclude them from having a vested interest in their partner’s satisfaction. Further, a study by Strait et al. (2013) argues that secure attachments formed in childhood correspond with secure romantic attachments in adulthood, which in turn results in higher marital quality and subsequent sexual satisfaction. In other words, if you develop positive views of self and others during formative years this will carry over into adulthood and help you form positive, highly satisfied romantic bonds. The happier you are in your romantic relationship the more satisfied you tend to be with your sex life. Further, attachment styles influence safer sex practices with anxiously attached individuals less likely to use barrier methods (Strachman & Impett, 2009). Together, these results showcase one way that our family-of-origin influences our sex lives.

Culture

The family culture we are raised in—macro and micro—also influences our sexual values and behaviors. Macro level culture refers to cultures that include/apply to large populations and geographic areas. Macro level influences include our race and ethnicity, religion, and national identity. Micro level culture occurs on a smaller scale and are encompassed within the larger society. Micro level influences may include your own family’s unique culture or a sub-culture you identify with in which you and the subculture members share “unique practices within a broader cultural group” (Solomon & Theiss, 2013, p. 43).

On a macro level, research shows that cultures have different orientations toward “approved” or “taboo” sexual acts. For instance, although normative in Western culture, romantic kissing isn’t universal and in some cultures, like the Thonga Tribe of South Africa, kissing is admonished. In fact, Jankowiak et al. (2015) found that across 168 cultures, romantic kissing was only found in 46% of the cultures studied (n = 77). Further, in some cultures anal sex is a condoned sexual practice, whereas others view it as a criminal act. For instance, sodomy laws, which prohibit oral and anal sex, were originally intended to prohibit recreational sex. However, the laws quickly shifted to discriminate against gay men (ACLU, 2022). As of 2020, 15 U.S. states still had sodomy laws on the books and three states, Kansas, Kentucky, and Texas, explicitly target same-sex behaviors in their laws.

Another macro level influence on sexual behavior is religion. In fact, numerous studies have found that religiosity, corresponds with age of first sex, number of sexual partners, and sexual regret (Chesire et al., 2019; Longest & Uecker, 2018). Longest and Uecker (2018), for instance, found that when religion was an important part of an adolescent’s life they tend to delay first sex, engage in less risky behaviors, and have few partners or casual sexual encounters. Similarly, Chesire et al. (2019) found that parent’s religiosity influenced children’s number of sexual partners through emerging adulthood.

Micro-level family influences tend to be unique to each family and are often rooted in how families do (or don’t) talk about sex.

Family Communication & Sex

“The Talk.” For some, conversations about sex with the parents are either non-existent or a one-time conversation focused on the mechanisms of the “birds & the bees.” Often times, these conversations focus on sexual education, or providing children with factual (and often times very basic) information about sex. These talks (often dreaded by parents and children) typically are aimed at reducing risky sexual behavior, defined as “experimenting with sex at a young age, participating with multiple sex partners, or having unprotected sex” (Coffelt, 2016, p. 375) as well as focusing on pregnancy prevention.

Although teaching logistics of sex and ways to protect oneself from STIs and unintentional pregnancy are important, it is also important that parents consider additional and more inclusive facets of sexual communication including discussions about pleasure and desire, sex outside of a heteronormative lens, sex and able-bodiness and chronic illness. Often children who don’t identify with gendered expectations and roles regarding sex or societal standards of who is or isn’t allowed to have sex feel ignored in conversations about sex. Flores et al. (2021) interviewed gay, bisexual, and queer male youths about their sex-related conversations with parents and found that parents often rooted the “sex talk” in heteronormative scripts. Discussions that did address their sexual orientation often perpetuated negative stereotypes (e.g., heightened risk of HIV/AIDS) and were emotional and reactive, highlighting the need for inclusive sex-education for parents.

Another study by Negy et al. (2016) examined parent-child communication about sex across four countries—United States, Spain, Peru, and Chile. The authors found that across the four countries, parental conversations about sex were often negative, conveying that sex outside of marriage was unacceptable. Further, parents rarely discussed sexual health matters including contraception, STIs, and sexual pleasure and desire. Interestingly, these restrictive conversations did not have an impact on adolescents’ sexual values, which were more liberal than their parents’ values, or delay sexual debut or reduce the number of sexual partners. These findings suggest that parents’ attempts at admonishing sexual activity through communication are unsuccessful. Thus, parents should be encouraged to have open and honest conversations about sexual activity with their children.

In lecture, we’ll outline strategies for successful parent-child communication about sex!

Food for Thought

Before lecture, reflect on the following questions:

- How would you characterize your communication with your parents about sex?

- What do you wish they had discussed with you? Hadn’t discussed with you?

- What were other sources of sexual education for you? A different family member? A friend? Media?