Now that we’re familiar with anatomy facts and terminology, we’re going to set the record straight about a few other terms and concepts that are crucial to our understanding of sexual behavior and communication—sex, gender, and sexual orientation.

You probably hear the words sex and gender all the time, often used interchangeably, and incorrectly! Additionally, many people conflate sex, gender, and sexual orientation, but as we’ll see in this chapter and in this week’s lectures and discussion, these concepts are multifaceted.

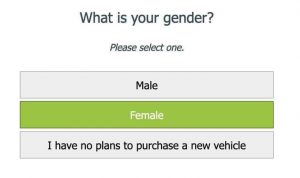

Have you ever seen items like this on surveys or forms you fill out either for a job, a doctor’s appointment, or even a research study?

Sex and Gender Questions in the Wild

Your gender:

- Male

- Female

- Other

OR

Your sex:

- Man

- Woman

- Other

OR this funny one that was floating around Twitter:

“The Three Genders.” Tweeted by the effexorcist @kahtrinuh

You may be thinking, yeah, I’ve seen these types of questions, what’s wrong with them? Well…

Sex and Gender

Despite the often erroneous interchangeable use of sex and gender, these two concepts are distinct. And although our society has made sex and gender inextricably linked, there are no biological connections between sex and gender. Additionally, gender has many layers to it, including our gender identity and expression.

The term biological sex refers to an individual’s biological composition, including their chromosomes, sexual organs (inside and outside), and hormones. Individuals with XY chromosomes, a penis and testicles, and androgen hormones (release by the testes), are referred to as biological males. Individuals with XX chromosomes, a vagina and ovaries, and estrogen hormones (released by the ovaries) are referred to as biological females. Remember, there are folks that may have a combination of these characteristics defined as intersex.

The term gender is a social construct that dictates how individuals of a certain biological sex should act—psychologically, socially, and culturally (Lehmiller, 2018). A gender role then is a set of expectations, cultural norms, and/or rules that prescribe how members of a certain sex “should” behave. In fact, gender roles of give very precise and limiting guidelines for how men and women can and should think, act, and feel. For instance, a “good” woman is supposed to be nurturing and a natural caregiver, therefore most women feel immense pressure to have children or act domestic (e.g., cooking, cleaning, maintaining the social calendar) in their romantic relationships, even if it’s not what they actually want! Or men may desperately want to talk about their feelings with someone and have a good cry, but Western culture has trained boys (and men) to “man up” and not express any weak or sensitive emotions. These gender roles then turn into gender stereotypes, which become overgeneralizations about the behaviors and characteristics of a certain sex, such as “boys will be boys” or “good girls…” do or don’t do certain things.

Reflection

Take a moment and think about how these concepts have shaped your identity and life. Specifically, ask yourself:

- What gender roles and stereotypes do we hold in the U.S. for men and women?

- How have these gender roles and stereotypes impact–my decisions? my behaviors? and, my relationships?

- How have these gender roles and stereotypes impacted my evaluation of others’ decisions? behaviors? and relationship>

Whereas gender is a broad term referring to overarching notions of behavior, gender identity refers to how an individual identifies, specifically one’s own “psychological perception of being male, female, neither, both or something in between.”

When an individual’s anatomical sex aligns with their gender identity that is referred to as cisgender with the prefix cis meaning “on the same side.” When an individual’s anatomical sex and gender identity do not align, for instance a biological male identifies as woman versus a man, like Laverne Cox, that is defined as transgender.

For others, their anatomical sex does not fall into any discrete category, either aligned or unaligned, such as man or woman. Instead, these individuals might describe feeling somewhere “in-between” or have fully different terms or experiences that capture their gender identity. Folks that connect with this descriptor are often referred to as non-binary and/or gender queer.

Going back to the survey examples at the beginning of the chapter when we are referring to someone based on their biological sex, we would use the terms male, female, or intersex. When we are referring to or asking someone about their gender (or gender identity) we would use the terms man, woman, non-binary, gender fluid, etc. (we’ll get into these terms and concepts more in lecture!). Although sex can often be ascertained, sometimes just visually, we do not know someone’s gender identity simply by looking at them, therefore it’s important to be careful when using language, such as pronouns (e.g., he or she) and not assume someone identifies as a man or woman simply based off of their anatomical sex. In fact, my eight year old will often refer to new friends as “they” versus making an assumption about “he” or “she” because he says, “I don’t know what they feel in their heart.” And that is another great way to think of gender identity, it’s what you feel in your heart.

Whereas gender identity refers to how someone feels about themselves, gender expression refers to how someone presents or expresses their gender identity. Gender identity can be expressed in numerous ways, including name, pronouns, clothing, hair, behavior, etc. Society has deemed certain behaviors or physical markers as “masculine” or “feminine” and belonging to men or women, respectfully. For instance, having long hair, wearing nail polish, and expressing emotions is often deemed feminine. Whereas having short hair, unmanicured nails, and being stoic is thought to be masculine. However, remember, there is nothing inherently “feminine” or “masculine” about these things, we’ve just decided who to attribute these behaviors too. And, amazingly, this is also fluid and what is considered masculine and feminine changes over time and varies by culture.

A cisgender individual tends to express their gender identity is “traditional” ways. For instance, a female who identifies as a woman likely wears clothes that are deemed “feminine”, has a feminine name, and uses she/her/hers pronouns.

In other instances, individuals express their gender in ways that go against “traditional” norms for femininity and masculinity. For instance, a male may paint their nails, wear make up, enjoy cooking and sewing, and freely express their emotions–all behaviors that are a non-no for “dudes.” As noted earlier, an individual may also identity and ay express a gender identity that contrasts with their biological sex, such as a trans man or trans woman. Collectively, GLAAD (Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation) defines these individuals as gender non-conforming. However, it is important to recognize that not all gender non-conforming folks identity as transgender and not all transgender folks are gender non-conforming.

As you can see, the concepts of sex and gender are multi-faceted. It’s important to understand these distinctions and use language appropriately and precisely so we are embracing, acknowledging, and respecting our own and others’ identity.

Sexual Orientation

Just like sex and gender can get muddled by folks, so can ideas about sexual orientation. According to renowned sex researcher Justin Lehmiller, PhD, there is no universally agreed upon definition of sexual orientation. Some people view it as who you are attracted to, others define it as the sexual behaviors you engage in, while others characterize it as a psychological construct. For the purposes of our class, we are going to utilize Lehmiller’s (2018) definition of sexual orientation as “the unique pattern of sexual and romantic desire, behavior, and identity that each person expresses” (p. 146).

Similar to sex and gender, U.S. culture likes to categorize sexual orientation into discrete categories. The primary categories you may often hear about are (1) heterosexual, attracted to members of the other sex; (2) homosexual, attracted to members of the same sex; and (3) bisexual, attracted to members of both sexes.

Additionally, individuals can be asexual, which is defined as not being sexually attracted to individuals or desiring sexual activity, or pansexual, attracted to members of all sex and gender identities. Like David on Schitt’s Creek said, someone who is pansexual is “into the wine not the label.”

Although discrete categories for sexual orientation exist, sexual orientation can also be conceived of as on a continuum, which allows for fluidity and flexibility.