For most (not all!), sex is a big part of their lives and relationships. Sex can be a great source of connection, pleasure, and fun! However, it can also be stressful, nerve wrecking, and a point of tension. In this chapter, we are going to explore the many facets of sex in relationships, from casual “hookups” to sex in later life, from sexual desires to sexual dysfunction, and the impact and of role of pornography and masturbation on our sex lives.

Sex in Casual Relationships

“Hooking up”, “Friends with Benefits”, and “Back Burner Relationships” those are just some of the labels given to a casual sexual relationship (CSR), which is a consensual sexual relationship between two individuals who are not in a committed, romantic relationship. As noted, CSRs can take on many forms and have varied outcomes.

Food For Thought

Reflect on the following questions:

- What does hooking up mean to you?

- What does friends with benefits mean to you?

- How are these two similar? Different?

- What other types of CSRs exist?

Although hookups tend to have a variety of definitions, typically hooksups are short-lived and carry no expectation for a continued sexual or romantic relationship (e.g., Monto & Carey, 2014). That is, a pair may hookup one time and even though they see each other out again, they might never engage in another sexual encounter. Further, hookups range in behavior from kissing to penetrative intercourse. Interestingly, however, penetrative intercourse is reported in less than half of all hookups (Monto & Carey, 2014).

Despite a greater prominence of the term hookup beginning in 2006 (in fact, there are no records of it in research databases in the 1990s) and media portrayals and concerns of “rampant sex on college campuses” (U.S. Catholic, 2008; Freitas, 2013) college students CSRs have not changed much, if at all, over the past three decades. In fact, across two waves of data from 1988-1996 and 2004-2012, Monto and Carey (2014) found that college students in the current wave (2004-2012) didn’t report having more sexual partners since age 18, more frequent sex, or more partners during the past year than college students in the 1988-1996 wave. Participants in the 2004-2012 wave were, however, more likely to report a hookup or friends with benefit relationship. However, the authors argue that this “modest” shift aligns with cultural changes in sexual “scripts” and they found no evidence of meaningful changes in sexual behavior that suggest “rampant sex on college campuses.”

Despite a lack of evidence supporting hookups as the dominant sexual pattern on campuses, hookup culture is ever looming, causing college students to overestimate the amount of hooking up that occurs on their campus. In fact, in her book American Hookup: The New Culture of Sex on Campus professor Lisa Wade found that 90% of students think hookup culture is rampant on campus (remember those norms we talked about in Chapter 3!).

However, Dr. Wade found that although 66% of the college-students that she interviewed had participated in a hookups, CSR weren’t “rampant” on campus. In fact, the majority of students had less than 9 hookups over their college career. More precisely, 28% had only 1-3 hookups throughout their college career and another 28% had only 4-9 hookups. A mere 14% had 10 or more hookups and 30% had never engaged in a hookup.

Even more revealing is that most students noted that they wanted a committed relationship (70% of women and 73% of men) and even more preferred dating to hooking up (95% women and 77% men).

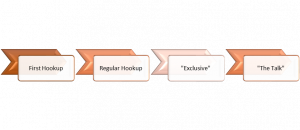

Further, the majority of students noted that many of their monogamous relationships started as a hookup leading Wade to articulate a hookup to relationship pathway:

An initial hookup turns into an established sexual hookup. At some point the partners establish that they are “exclusive”, meaning they are no longer hooking up with other folks (i.e., monogamous), but still not in a relationship. After spending time as an exclusive hookup partners eventually have “the talk” in which they solidify that their relationship status has moved from hooking up to dating.

Although hooking up can be enjoyable, fun, and lead to a romantic relationship, it also has it downsides, which we’ll discuss in class. Further, listen to Dr. Wade discuss the promises and perils of hookup culture.

Listen Up!

Listen to Dr. Lisa Wade discuss her book and some drawbacks of hookup culture on the Hidden Brain podcast:

In addition to hookups, another form of CSRs are friends with benefits relationships (FWBR). Similar to hookups, various definitions of FWBR exists. However, drawing from the research Trask (2016) identified two common characteristics of FWBR:

- 1) Sexual encounters are consistent, meaning they happen more than once.

- 2) Intimacy (e.g., relational closeness or romantic love) is experienced, but commitment is not.

Combined, these two characteristics allow FWBs to engage in sexual relationships with one another while still developing and maintaining sexual and romantic relationships with others.

FWB often appreciate engaging in sex in a safe and trusted environment. As such, compared to the other CSRs, FWBs use barrier methods (e.g., condoms or dental dams) more frequently when engaging in oral and penetrative sex (Lehmiller, Vanderdrift & Kelly, 2014).

Despite what romantic comedies tell us, for most FWBs (or at least one person in the FWBR) progression into a romantic relationship often isn’t desired or common (Stafford et al., 2014).

In lecture, we’ll discuss the advantages and disadvantages of FWBR.

Sex in Committed Partnerships

Sex in a long-term, monogamous relationship can be amazing as trust, love, and commitment can enhance sexual desire, allow us to engage in sexual experimentation, and foster an environment for open sexual communication. However, sex in committed partnerships isn’t all sunshine and lollipops. Sex in long-term relationships is influenced by societal pressures like expectations regarding the frequency of sex, external factors like caregiving or work, and health related issues that pop-up in the natural course of our lifespan, such as sexual dysfunctions. In other words, sex continues to be complicated even when you’re in a long term relationship. But, don’t fret—there are ways to maintain and even enhance our sexual relationships no matter what society or life throws at us!

Expectations and Challenges

Media and society often put an immense amount of pressure on married couples to maintain active sex lives. And although sexual satisfaction has been shown to correspond with relationship satisfaction (Noland, 2010) the pressure to maintain “hot and spicy” sex lives is often placed on women and center’s their husband’s desires and pleasure. For instance, women often face misogynistic pressures after childbirth to not only bounce back physically, but sexually as well. The 6-week post-birth check-up is often the time women get the “green light” that they are physically okay to return to intercourse, without any consideration for their emotional or psychological readiness. Even worse is the “husband stitch,” the extra stitch a doctor will add when suturing a woman after childbirth to ensure a “tight” vaginal opening (and yes, this really happens!). Although women receive the bulk of sexual pressure, men are not entirely free from sexual expectations. Men, as noted previously, are expected to want to have sex at any given moment and are expected to “be able to perform” meaning have an erection and orgasm during every single sexual encounter. Further, both husbands and wives often accept the cultural myth that men need more sex and sometimes even use this as justification for extra-marital affairs (Elliott & Umberson, 2008).

Unfortunately, these pressures can harm our sex lives and do not reflect the realities of married couples (or other long-term partners) sexual behaviors. In fact, recent data shows from the General Social Survey reports that moderate sexual activity was most frequent among couples. Specifically, 19% report having sex 2-3 times per month, 17% reporting having sex once a month. Twenty-five percent reported having sex weekly, whereas only 16% had sex 2-3 times per week, and a mere 5% had sex four or more time per week. Ten percent of participants reported not having sex in the past year and 7% reported having sex only once or twice in the past year.

Thus, although cultural expectations suggest frequent sex is all the rage, that doesn’t align with reality. Additionally, numerous factors both external and internal can make sustaining an active sex life difficult.

Sexual Challenges in Long-Term Relationships

Couples are often hesitant to discuss sexual difficulties with each other or outsiders as they feel they are a sign of “failure” or that something is wrong with them or their partner. However, encountering hiccups in our sex lives is completely normal.

While some issues may be short-lived and can be easily addressed by the couple, others may be more serious and long-term and require outside intervention, such as medication or counseling.

One issue long-term couples grapple with is what they perceive to be a “waning desire.” Couples may become worried when they lose the “butterfly” feeling, believing it means something is wrong with their relationship. However, nothing is wrong, it’s just a normal physiological process. When we first meet someone desirable dopamine is released, often at high levels, making us focused and excited about our object of affection. Further, norepinephrine levels go up, and these may make us feel nervous and a bit cautious. Neuroscientists also note that lust (not love) ignites the pleasure center in our basal ganglia which makes our heart rate increase, our hands get clammy, and also increases our focus on the person. Moreover, our limbic system, which is the part of our brain that controls behavioral and emotional responses, ignites our vagus nerve that connects our brain to our gut. Together, these processes make us feel nervous and excited and like our stomach is literally “doing summersaults” or that it is filled with butterflies.

This butterfly feeling doesn’t and can’t last forever—physiologically. In fact, scientists argue that within five years of being with a partner our dopamine and endorphins drop and are often only mildly elevated compared to the high levels we experienced in the early days. However, this decrease or absence of the “butterfly feeling” doesn’t mean we don’t love our partner or we are not attracted to them. In fact, Dr. Nicole Gravagna says “True love is a well-being experience that does not include nervousness or excitement.” Thus, when the butterflies go away, it just signals that you are in a new phase of your relationship.

The Brain In Love: TED Talk

Watch biological anthropologist, Dr. Helen Fischer, discuss The Brain in Love

Sexual Dysfunction

Partners in long-term relationships may at some point have to navigate sexual dysfunction, defined as “an impairment in one or more areas of sexual dysfunction resulting in significant levels of subjective distress” (DSM 5). There are four main areas of sexual dysfunction: 1) desire; 2) arousal; 3) orgasm, and 4) sexual pain.

These dysfunctions can stem from a variety of causes such as biological, including physical disease or illness, prescription medication side effects, and excessive consumption of alcohol and drugs. Psychological factors include mental health diagnoses such as depression, anxiety, or bipolar disorder, performance anxiety, and myriad pressures related to daily life (e.g., work, caregiving). Social and cultural influences on sexual dysfunction include learned negative attitudes about sexuality (ergtophobia), negative or traumatic sexual experiences, and the deterioration of the interpersonal relationship, often stemming from a lack of communication. Despite the scary sounding notion of “dysfunction” it’s fairly common. In fact, about 42% of males and 51% of females who are sexually active reported at least one sexual problem in the last year.

Keeping things Interesting: Sexual Desires, Fantasies, Pornography, and Masturbation

One of the wonderful parts of being in a long-term committed sexual relationship is the ability to explore our sexual selves. Discussing sexual desires, incorporating pornography, and engaging in masturbation—self or mutual—can enhance a couple’s sex life.

Sexual Desires & Sexual Fantasies

Often, individuals hesitate to share sexual desires and fantasies for fear of being judged by their partner. People often internalize society’s ideas about what is “normal” sexual behavior and sexual desires and fantasies tend to go against these prescribed norms, which is why folks keep these to themselves. However, one way to feel more comfortable discussing desires and fantasies is to distinguish between the two. A sexual desire is a strong feeling of wanting something or for something to happen, whereas a sexual fantasy is the ability to imagine things, even things that are impossible or improbable.

As we will discuss in class, a sexual fantasy isn’t always a sexual desire. In fact, we way have some fantasies that we never want to act, but others we do. For instance, an individual may fantasize about bringing a third party into the bedroom, but not have an actual desire to act on that fantasy. Conversely, a different person may very much wish to bring another partner into their relationship and want to make their fantasy a reality. In lecture, we’ll discuss how we can decided if we want to turn a fantasy into reality and how to have those conversations with your partner(s).

Pornography & Masturbation

Another area of sexual life that is often misperceived is the role pornography and masturbation can play in our sex lives. Often pornography gets a bad rap, with media extolling the negative and dangerous effects of pornography. Although pornography can be harmful, such as creating unrealistic expectations about what sex should look like, upholding distorted ideas about what bodies and genitals looks like, or, in some cases, correspond with acceptance of violence against women, pornography isn’t the evil monster media and politicians make it out to be.

In fact, Pornography, sexually explicit material that has the intent of producing arousal (Lehmiller, 2018, p. 402) and erotica, “depictions of sex that evoke themes of mutual attraction and usually incorporate some emotional component in addition to the sex act itself” (Lehmiller, 2018, p. 403), can be helpful to a couple’s relationship. Some studies have shown that couples who use pornography together are more sexually satisfied than those that don’t use it (Lehmiller, 2018). Collaborative porn watching also corresponds with relational and sexual intimacy (Huntington et al., 2021) . One reason is that pornography may allow couples to experiment and “try out” fantasies vicariously. Additionally, using pornography helps couples introduce excitement and novelty into their sex lives (Frederick, Lever, Gillespie, & Garcia, 2017). However, porn can be detrimental to a relationship, especially if one partner uses it excessively or in lieu of being intimate with their partner.

Communicating About Sex

Even in long-term partnerships, communicating about sex can be difficult. Our upbringing, culture, or religion may make it difficult to talk openly about sex. Additionally, talking about sex is a vulnerable process and can threaten our or our partner’s “face,” the positive public image people wish to portray to others (Goffman, 1955). Despite these factors, talking about sex doesn’t always have to be tricky.

One way to enhance sexual communication in relationships is to set the stage for strong communication in other aspects of your relationship. First, it’s important to engage in what researchers call “mundane talk” or everyday conversations (Baxter & Goldsmith, 1996; Duck, 1994), such as chatting about one another’s day, gossiping, and joking around. Frequent engagement in mundane or everyday talk is associated with feelings of connection and relationship satisfaction (Schrodt, 2016). As previously noted, relational satisfaction and communication satisfaction are closely linked and relational satisfaction corresponds with sexual satisfaction. Thus, creating a strong communication foundation surrounding everyday conversations creates a climate in which communicating, even about touchy subjects, is easier.

Another way to enhance communication, including sexual communication, is to connect with our partner’s emotional bids. An emotional bid is an action a partner takes to signal they are seeking an emotional connection with their partner (Gottman, 2022). Emotional bids can range from overt (e.g., “Can we talk?” to hinting (e.g., “Gosh, my shoulders are really stiff”) and can be about an emotional connection or help with a concrete task. How we respond to emotional bids is important. Gottman (2022) outlines three ways partners can respond to emotional bids:

- Turning toward: Acknowledge and engage with your partner.

- Turning away: Ignore your partner or “miss” the bid.

- Turning against: Reject the bid in an argumentative or belligerent way.

When we turn toward are partner’s bid we make them feel seen, heard, and understood, whereas turning away or worse, against, makes partners feel ignored, devalued, or rejected. When we create a climate where emotional bids are responded to positively we create an environment that communicates trust, emotional connection, and acceptance. This type of relational environment makes it much easier to talk about our sexual expectations, frustrations, and desires and fantasies.