14 Module 14: Evaluating Community Practice

Overview of Readings

Community Toolbox readings, provided below.

- Chapter 36, Section 1: A Framework for Program Evaluation: A Gateway to Tools (main section)

- Chapter 36, Section 5. Developing and Evaluation Plan (main section)

Suarez (2022). What Does Black Feminist Evaluation Look Like? https://nonprofitquarterly.org/what-does-black-feminist-evaluation-look-like/?mc_cid=93e79fcda5&mc_eid=170e62a4d7

Explore:

CDC Program Evaluation: https://www.cdc.gov/evaluation/index.htm Especially CDC Approach to Evaluation

Community Toolbox

Chapter 36, Section 1: A Framework for Program Evaluation: A Gateway to Tools

| Learn how program evaluation makes it easier for everyone involved in community health and development work to evaluate their efforts. |

This section is adapted from the article “Recommended Framework for Program Evaluation in Public Health Practice,” by Bobby Milstein, Scott Wetterhall, and the CDC Evaluation Working Group.

Around the world, there exist many programs and interventions developed to improve conditions in local communities. Communities come together to reduce the level of violence that exists, to work for safe, affordable housing for everyone, or to help more students do well in school, to give just a few examples.

But how do we know whether these programs are working? If they are not effective, and even if they are, how can we improve them to make them better for local communities? And finally, how can an organization make intelligent choices about which promising programs are likely to work best in their community?

Over the past years, there has been a growing trend towards the better use of evaluation to understand and improve practice.The systematic use of evaluation has solved many problems and helped countless community-based organizations do what they do better.

Despite an increased understanding of the need for – and the use of – evaluation, however, a basic agreed-upon framework for program evaluation has been lacking. In 1997, scientists at the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recognized the need to develop such a framework. As a result of this, the CDC assembled an Evaluation Working Group comprised of experts in the fields of public health and evaluation. Members were asked to develop a framework that summarizes and organizes the basic elements of program evaluation. This Community Tool Box section describes the framework resulting from the Working Group’s efforts.

Before we begin, however, we’d like to offer some definitions of terms that we will use throughout this section.

By evaluation, we mean the systematic investigation of the merit, worth, or significance of an object or effort. Evaluation practice has changed dramatically during the past three decades – new methods and approaches have been developed and it is now used for increasingly diverse projects and audiences.

Throughout this section, the term program is used to describe the object or effort that is being evaluated. It may apply to any action with the goal of improving outcomes for whole communities, for more specific sectors (e.g., schools, work places), or for sub-groups (e.g., youth, people experiencing violence or HIV/AIDS). This definition is meant to be very broad.

Examples of different types of programs include:

- Direct service interventions (e.g., a program that offers free breakfast to improve nutrition for grade school children)

- Community mobilization efforts (e.g., organizing a boycott of California grapes to improve the economic well-being of farm workers)

- Research initiatives (e.g., an effort to find out whether inequities in health outcomes based on race can be reduced)

- Surveillance systems (e.g., whether early detection of school readiness improves educational outcomes)

- Advocacy work (e.g., a campaign to influence the state legislature to pass legislation regarding tobacco control)

- Social marketing campaigns (e.g., a campaign in the Third World encouraging mothers to breast-feed their babies to reduce infant mortality)

- Infrastructure building projects (e.g., a program to build the capacity of state agencies to support community development initiatives)

- Training programs (e.g., a job training program to reduce unemployment in urban neighborhoods)

- Administrative systems (e.g., an incentive program to improve efficiency of health services)

Program evaluation – the type of evaluation discussed in this section – is an essential organizational practice for all types of community health and development work. It is a way to evaluate the specific projects and activities community groups may take part in, rather than to evaluate an entire organization or comprehensive community initiative.

Stakeholders refer to those who care about the program or effort. These may include those presumed to benefit (e.g., children and their parents or guardians), those with particular influence (e.g., elected or appointed officials), and those who might support the effort (i.e., potential allies) or oppose it (i.e., potential opponents). Key questions in thinking about stakeholders are: Who cares? What do they care about?

This section presents a framework that promotes a common understanding of program evaluation. The overall goal is to make it easier for everyone involved in community health and development work to evaluate their efforts.

Why evaluate community health and development programs?

The type of evaluation we talk about in this section can be closely tied to everyday program operations. Our emphasis is on practical, ongoing evaluation that involves program staff, community members, and other stakeholders, not just evaluation experts. This type of evaluation offers many advantages for community health and development professionals.

For example, it complements program management by:

- Helping to clarify program plans

- Improving communication among partners

- Gathering the feedback needed to improve and be accountable for program effectiveness

It’s important to remember, too, that evaluation is not a new activity for those of us working to improve our communities. In fact, we assess the merit of our work all the time when we ask questions, consult partners, make assessments based on feedback, and then use those judgments to improve our work. When the stakes are low, this type of informal evaluation might be enough. However, when the stakes are raised – when a good deal of time or money is involved, or when many people may be affected – then it may make sense for your organization to use evaluation procedures that are more formal, visible, and justifiable.

How do you evaluate a specific program?

Before your organization starts with a program evaluation, your group should be very clear about the answers to the following questions:

- What will be evaluated?

- What criteria will be used to judge program performance?

- What standards of performance on the criteria must be reached for the program to be considered successful?

- What evidence will indicate performance on the criteria relative to the standards?

- What conclusions about program performance are justified based on the available evidence?

To clarify the meaning of each, let’s look at some of the answers for Drive Smart, a hypothetical program begun to stop drunk driving.

- What will be evaluated?

- Drive Smart, a program focused on reducing drunk driving through public education and intervention.

- What criteria will be used to judge program performance?

- The number of community residents who are familiar with the program and its goals

- The number of people who use “Safe Rides” volunteer taxis to get home

- The percentage of people who report drinking and driving

- The reported number of single car night time crashes (This is a common way to try to determine if the number of people who drive drunk is changing)

- What standards of performance on the criteria must be reached for the program to be considered successful?

- 80% of community residents will know about the program and its goals after the first year of the program

- The number of people who use the “Safe Rides” taxis will increase by 20% in the first year

- The percentage of people who report drinking and driving will decrease by 20% in the first year

- The reported number of single car night time crashes will decrease by 10 % in the program’s first two years

- What evidence will indicate performance on the criteria relative to the standards?

- A random telephone survey will demonstrate community residents’ knowledge of the program and changes in reported behavior

- Logs from “Safe Rides” will tell how many people use their services

- Information on single car night time crashes will be gathered from police records

- What conclusions about program performance are justified based on the available evidence?

- Are the changes we have seen in the level of drunk driving due to our efforts, or something else? Or (if no or insufficient change in behavior or outcome,)

- Should Drive Smart change what it is doing, or have we just not waited long enough to see results?

The following framework provides an organized approach to answer these questions.

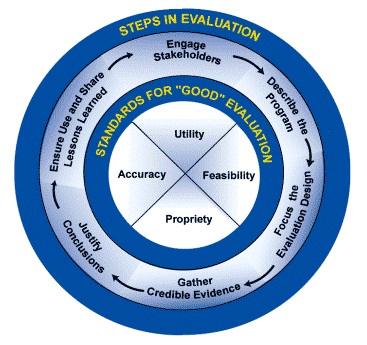

A framework for program evaluation

Program evaluation offers a way to understand and improve community health and development practice using methods that are useful, feasible, proper, and accurate. The framework described below is a practical non-prescriptive tool that summarizes in a logical order the important elements of program evaluation.

The framework contains two related dimensions:

- Steps in evaluation practice, and

- Standards for “good” evaluation.

The six connected steps of the framework are actions that should be a part of any evaluation. Although in practice the steps may be encountered out of order, it will usually make sense to follow them in the recommended sequence. That’s because earlier steps provide the foundation for subsequent progress. Thus, decisions about how to carry out a given step should not be finalized until prior steps have been thoroughly addressed.

However, these steps are meant to be adaptable, not rigid. Sensitivity to each program’s unique context (for example, the program’s history and organizational climate) is essential for sound evaluation. They are intended to serve as starting points around which community organizations can tailor an evaluation to best meet their needs.

- Engage stakeholders

- Describe the program

- Focus the evaluation design

- Gather credible evidence

- Justify conclusions

- Ensure use and share lessons learned

Understanding and adhering to these basic steps will improve most evaluation efforts.

The second part of the framework is a basic set of standards to assess the quality of evaluation activities. There are 30 specific standards, organized into the following four groups:

- Utility

- Feasibility

- Propriety

- Accuracy

These standards help answer the question, “Will this evaluation be a ‘good’ evaluation?” They are recommended as the initial criteria by which to judge the quality of the program evaluation efforts.

Engage Stakeholders

Stakeholders are people or organizations that have something to gain or lose from what will be learned from an evaluation, and also in what will be done with that knowledge. Evaluation cannot be done in isolation. Almost everything done in community health and development work involves partnerships – alliances among different organizations, board members, those affected by the problem, and others. Therefore, any serious effort to evaluate a program must consider the different values held by the partners. Stakeholders must be part of the evaluation to ensure that their unique perspectives are understood. When stakeholders are not appropriately involved, evaluation findings are likely to be ignored, criticized, or resisted.

However, if they are part of the process, people are likely to feel a good deal of ownership for the evaluation process and results. They will probably want to develop it, defend it, and make sure that the evaluation really works.

That’s why this evaluation cycle begins by engaging stakeholders. Once involved, these people will help to carry out each of the steps that follows.

Three principle groups of stakeholders are important to involve:

- People or organizations involved in program operations may include community members, sponsors, collaborators, coalition partners, funding officials, administrators, managers, and staff.

- People or organizations served or affected by the program may include clients, family members, neighborhood organizations, academic institutions, elected and appointed officials, advocacy groups, and community residents. Individuals who are openly skeptical of or antagonistic toward the program may also be important to involve. Opening an evaluation to opposing perspectives and enlisting the help of potential program opponents can strengthen the evaluation’s credibility.

Likewise, individuals or groups who could be adversely or inadvertently affected by changes arising from the evaluation have a right to be engaged. For example, it is important to include those who would be affected if program services were expanded, altered, limited, or ended as a result of the evaluation.

- Primary intended users of the evaluation are the specific individuals who are in a position to decide and/or do something with the results.They shouldn’t be confused with primary intended users of the program, although some of them should be involved in this group. In fact, primary intended users should be a subset of all of the stakeholders who have been identified. A successful evaluation will designate primary intended users, such as program staff and funders, early in its development and maintain frequent interaction with them to be sure that the evaluation specifically addresses their values and needs.

The amount and type of stakeholder involvement will be different for each program evaluation. For instance, stakeholders can be directly involved in designing and conducting the evaluation. They can be kept informed about progress of the evaluation through periodic meetings, reports, and other means of communication.

It may be helpful, when working with a group such as this, to develop an explicit process to share power and resolve conflicts. This may help avoid overemphasis of values held by any specific stakeholder.

Describe the Program

A program description is a summary of the intervention being evaluated. It should explain what the program is trying to accomplish and how it tries to bring about those changes. The description will also illustrate the program’s core components and elements, its ability to make changes, its stage of development, and how the program fits into the larger organizational and community environment.

How a program is described sets the frame of reference for all future decisions about its evaluation. For example, if a program is described as, “attempting to strengthen enforcement of existing laws that discourage underage drinking,” the evaluation might be very different than if it is described as, “a program to reduce drunk driving by teens.” Also, the description allows members of the group to compare the program to other similar efforts, and it makes it easier to figure out what parts of the program brought about what effects.

Moreover, different stakeholders may have different ideas about what the program is supposed to achieve and why. For example, a program to reduce teen pregnancy may have some members who believe this means only increasing access to contraceptives, and other members who believe it means only focusing on abstinence.

Evaluations done without agreement on the program definition aren’t likely to be very useful. In many cases, the process of working with stakeholders to develop a clear and logical program description will bring benefits long before data are available to measure program effectiveness.

There are several specific aspects that should be included when describing a program.

Statement of need

A statement of need describes the problem, goal, or opportunity that the program addresses; it also begins to imply what the program will do in response. Important features to note regarding a program’s need are: the nature of the problem or goal, who is affected, how big it is, and whether (and how) it is changing.

Expectations

Expectations are the program’s intended results. They describe what the program has to accomplish to be considered successful. For most programs, the accomplishments exist on a continuum (first, we want to accomplish X… then, we want to do Y…). Therefore, they should be organized by time ranging from specific (and immediate) to broad (and longer-term) consequences. For example, a program’s vision, mission, goals, and objectives, all represent varying levels of specificity about a program’s expectations.

Activities

Activities are everything the program does to bring about changes. Describing program components and elements permits specific strategies and actions to be listed in logical sequence. This also shows how different program activities, such as education and enforcement, relate to one another. Describing program activities also provides an opportunity to distinguish activities that are the direct responsibility of the program from those that are conducted by related programs or partner organizations. Things outside of the program that may affect its success, such as harsher laws punishing businesses that sell alcohol to minors, can also be noted.

Resources

Resources include the time, talent, equipment, information, money, and other assets available to conduct program activities. Reviewing the resources a program has tells a lot about the amount and intensity of its services. It may also point out situations where there is a mismatch between what the group wants to do and the resources available to carry out these activities. Understanding program costs is a necessity to assess the cost-benefit ratio as part of the evaluation.

Stage of development

A program’s stage of development reflects its maturity. All community health and development programs mature and change over time. People who conduct evaluations, as well as those who use their findings, need to consider the dynamic nature of programs. For example, a new program that just received its first grant may differ in many respects from one that has been running for over a decade.

At least three phases of development are commonly recognized: planning, implementation, and effects or outcomes. In the planning stage, program activities are untested and the goal of evaluation is to refine plans as much as possible. In the implementation phase, program activities are being field tested and modified; the goal of evaluation is to see what happens in the “real world” and to improve operations. In the effects stage, enough time has passed for the program’s effects to emerge; the goal of evaluation is to identify and understand the program’s results, including those that were unintentional.

Context

A description of the program’s context considers the important features of the environment in which the program operates. This includes understanding the area’s history, geography, politics, and social and economic conditions, and also what other organizations have done. A realistic and responsive evaluation is sensitive to a broad range of potential influences on the program. An understanding of the context lets users interpret findings accurately and assess their generalizability. For example, a program to improve housing in an inner-city neighborhood might have been a tremendous success, but would likely not work in a small town on the other side of the country without significant adaptation.

Logic model

A logic model synthesizes the main program elements into a picture of how the program is supposed to work. It makes explicit the sequence of events that are presumed to bring about change. Often this logic is displayed in a flow-chart, map, or table to portray the sequence of steps leading to program results.

Creating a logic model allows stakeholders to improve and focus program direction. It reveals assumptions about conditions for program effectiveness and provides a frame of reference for one or more evaluations of the program. A detailed logic model can also be a basis for estimating the program’s effect on endpoints that are not directly measured. For example, it may be possible to estimate the rate of reduction in disease from a known number of persons experiencing the intervention if there is prior knowledge about its effectiveness.

The breadth and depth of a program description will vary for each program evaluation. And so, many different activities may be part of developing that description. For instance, multiple sources of information could be pulled together to construct a well-rounded description. The accuracy of an existing program description could be confirmed through discussion with stakeholders. Descriptions of what’s going on could be checked against direct observation of activities in the field. A narrow program description could be fleshed out by addressing contextual factors (such as staff turnover, inadequate resources, political pressures, or strong community participation) that may affect program performance.

Focus the Evaluation Design

By focusing the evaluation design, we mean doing advance planning about where the evaluation is headed, and what steps it will take to get there. It isn’t possible or useful for an evaluation to try to answer all questions for all stakeholders; there must be a focus. A well-focused plan is a safeguard against using time and resources inefficiently.

Depending on what you want to learn, some types of evaluation will be better suited than others. However, once data collection begins, it may be difficult or impossible to change what you are doing, even if it becomes obvious that other methods would work better. A thorough plan anticipates intended uses and creates an evaluation strategy with the greatest chance to be useful, feasible, proper, and accurate.

Among the issues to consider when focusing an evaluation are:

Purpose

Purpose refers to the general intent of the evaluation. A clear purpose serves as the basis for the design, methods, and use of the evaluation. Taking time to articulate an overall purpose will stop your organization from making uninformed decisions about how the evaluation should be conducted and used.

There are at least four general purposes for which a community group might conduct an evaluation:

- To gain insight.This happens, for example, when deciding whether to use a new approach (e.g., would a neighborhood watch program work for our community?) Knowledge from such an evaluation will provide information about its practicality. For a developing program, information from evaluations of similar programs can provide the insight needed to clarify how its activities should be designed.

- To improve how things get done.This is appropriate in the implementation stage when an established program tries to describe what it has done. This information can be used to describe program processes, to improve how the program operates, and to fine-tune the overall strategy. Evaluations done for this purpose include efforts to improve the quality, effectiveness, or efficiency of program activities.

- To determine what the effects of the program are. Evaluations done for this purpose examine the relationship between program activities and observed consequences. For example, are more students finishing high school as a result of the program? Programs most appropriate for this type of evaluation are mature programs that are able to state clearly what happened and who it happened to. Such evaluations should provide evidence about what the program’s contribution was to reaching longer-term goals such as a decrease in child abuse or crime in the area. This type of evaluation helps establish the accountability, and thus, the credibility, of a program to funders and to the community.

- To affect those who participate in it. The logic and reflection required of evaluation participants can itself be a catalyst for self-directed change. And so, one of the purposes of evaluating a program is for the process and results to have a positive influence. Such influences may:

- Empower program participants (for example, being part of an evaluation can increase community members’ sense of control over the program);

- Supplement the program (for example, using a follow-up questionnaire can reinforce the main messages of the program);

- Promote staff development (for example, by teaching staff how to collect, analyze, and interpret evidence); or

- Contribute to organizational growth (for example, the evaluation may clarify how the program relates to the organization’s mission).

Users

Users are the specific individuals who will receive evaluation findings. They will directly experience the consequences of inevitable trade-offs in the evaluation process. For example, a trade-off might be having a relatively modest evaluation to fit the budget with the outcome that the evaluation results will be less certain than they would be for a full-scale evaluation. Because they will be affected by these tradeoffs, intended users have a right to participate in choosing a focus for the evaluation. An evaluation designed without adequate user involvement in selecting the focus can become a misguided and irrelevant exercise. By contrast, when users are encouraged to clarify intended uses, priority questions, and preferred methods, the evaluation is more likely to focus on things that will inform (and influence) future actions.

Uses

Uses describe what will be done with what is learned from the evaluation. There is a wide range of potential uses for program evaluation. Generally speaking, the uses fall in the same four categories as the purposes listed above: to gain insight, improve how things get done, determine what the effects of the program are, and affect participants. The following list gives examples of uses in each category.

Some specific examples of evaluation uses

-

To gain insight:

- Assess needs and wants of community members

- Identify barriers to use of the program

- Learn how to best describe and measure program activities

-

To improve how things get done:

- Refine plans for introducing a new practice

- Determine the extent to which plans were implemented

- Improve educational materials

- Enhance cultural competence

- Verify that participants’ rights are protected

- Set priorities for staff training

- Make mid-course adjustments

- Clarify communication

- Determine if client satisfaction can be improved

- Compare costs to benefits

- Find out which participants benefit most from the program

- Mobilize community support for the program

-

To determine what the effects of the program are:

- Assess skills development by program participants

- Compare changes in behavior over time

- Decide where to allocate new resources

- Document the level of success in accomplishing objectives

- Demonstrate that accountability requirements are fulfilled

- Use information from multiple evaluations to predict the likely effects of similar programs

-

To affect participants:

- Reinforce messages of the program

- Stimulate dialogue and raise awareness about community issues

- Broaden consensus among partners about program goals

- Teach evaluation skills to staff and other stakeholders

- Gather success stories

- Support organizational change and improvement

Questions

The evaluation needs to answer specific questions. Drafting questions encourages stakeholders to reveal what they believe the evaluation should answer. That is, what questions are more important to stakeholders? The process of developing evaluation questions further refines the focus of the evaluation.

Methods

The methods available for an evaluation are drawn from behavioral science and social research and development. Three types of methods are commonly recognized. They are experimental, quasi-experimental, and observational or case study designs. Experimental designs use random assignment to compare the effect of an intervention between otherwise equivalent groups (for example, comparing a randomly assigned group of students who took part in an after-school reading program with those who didn’t). Quasi-experimental methods make comparisons between groups that aren’t equal (e.g. program participants vs. those on a waiting list) or use of comparisons within a group over time, such as in an interrupted time series in which the intervention may be introduced sequentially across different individuals, groups, or contexts. Observational or case study methods use comparisons within a group to describe and explain what happens (e.g., comparative case studies with multiple communities).

No design is necessarily better than another. Evaluation methods should be selected because they provide the appropriate information to answer stakeholders’ questions, not because they are familiar, easy, or popular. The choice of methods has implications for what will count as evidence, how that evidence will be gathered, and what kind of claims can be made. Because each method option has its own biases and limitations, evaluations that mix methods are generally more robust.

Over the course of an evaluation, methods may need to be revised or modified. Circumstances that make a particular approach useful can change. For example, the intended use of the evaluation could shift from discovering how to improve the program to helping decide about whether the program should continue or not. Thus, methods may need to be adapted or redesigned to keep the evaluation on track.

Agreements

Agreements summarize the evaluation procedures and clarify everyone’s roles and responsibilities. An agreement describes how the evaluation activities will be implemented. Elements of an agreement include statements about the intended purpose, users, uses, and methods, as well as a summary of the deliverables, those responsible, a timeline, and budget.

The formality of the agreement depends upon the relationships that exist between those involved. For example, it may take the form of a legal contract, a detailed protocol, or a simple memorandum of understanding. Regardless of its formality, creating an explicit agreement provides an opportunity to verify the mutual understanding needed for a successful evaluation. It also provides a basis for modifying procedures if that turns out to be necessary.

As you can see, focusing the evaluation design may involve many activities. For instance, both supporters and skeptics of the program could be consulted to ensure that the proposed evaluation questions are politically viable. A menu of potential evaluation uses appropriate for the program’s stage of development could be circulated among stakeholders to determine which is most compelling. Interviews could be held with specific intended users to better understand their information needs and timeline for action. Resource requirements could be reduced when users are willing to employ more timely but less precise evaluation methods.

Gather Credible Evidence

Credible evidence is the raw material of a good evaluation. The information learned should be seen by stakeholders as believable, trustworthy, and relevant to answer their questions. This requires thinking broadly about what counts as “evidence.” Such decisions are always situational; they depend on the question being posed and the motives for asking it. For some questions, a stakeholder’s standard for credibility could demand having the results of a randomized experiment. For another question, a set of well-done, systematic observations such as interactions between an outreach worker and community residents, will have high credibility. The difference depends on what kind of information the stakeholders want and the situation in which it is gathered.

Context matters! In some situations, it may be necessary to consult evaluation specialists. This may be especially true if concern for data quality is especially high. In other circumstances, local people may offer the deepest insights. Regardless of their expertise, however, those involved in an evaluation should strive to collect information that will convey a credible, well-rounded picture of the program and its efforts.

Having credible evidence strengthens the evaluation results as well as the recommendations that follow from them. Although all types of data have limitations, it is possible to improve an evaluation’s overall credibility. One way to do this is by using multiple procedures for gathering, analyzing, and interpreting data. Encouraging participation by stakeholders can also enhance perceived credibility. When stakeholders help define questions and gather data, they will be more likely to accept the evaluation’s conclusions and to act on its recommendations.

The following features of evidence gathering typically affect how credible it is seen as being:

Indicators

Indicators translate general concepts about the program and its expected effects into specific, measurable parts.

Examples of indicators include:

- The program’s capacity to deliver services

- The participation rate

- The level of client satisfaction

- The amount of intervention exposure (how many people were exposed to the program, and for how long they were exposed)

- Changes in participant behavior

- Changes in community conditions or norms

- Changes in the environment (e.g., new programs, policies, or practices)

- Longer-term changes in population health status (e.g., estimated teen pregnancy rate in the county)

Indicators should address the criteria that will be used to judge the program. That is, they reflect the aspects of the program that are most meaningful to monitor. Several indicators are usually needed to track the implementation and effects of a complex program or intervention.

One way to develop multiple indicators is to create a “balanced scorecard,” which contains indicators that are carefully selected to complement one another. According to this strategy, program processes and effects are viewed from multiple perspectives using small groups of related indicators. For instance, a balanced scorecard for a single program might include indicators of how the program is being delivered; what participants think of the program; what effects are observed; what goals were attained; and what changes are occurring in the environment around the program.

Another approach to using multiple indicators is based on a program logic model, such as we discussed earlier in the section. A logic model can be used as a template to define a full spectrum of indicators along the pathway that leads from program activities to expected effects. For each step in the model, qualitative and/or quantitative indicators could be developed.

Indicators can be broad-based and don’t need to focus only on a program’s long -term goals. They can also address intermediary factors that influence program effectiveness, including such intangible factors as service quality, community capacity, or inter -organizational relations. Indicators for these and similar concepts can be created by systematically identifying and then tracking markers of what is said or done when the concept is expressed.

In the course of an evaluation, indicators may need to be modified or new ones adopted. Also, measuring program performance by tracking indicators is only one part of evaluation, and shouldn’t be confused as a basis for decision making in itself. There are definite perils to using performance indicators as a substitute for completing the evaluation process and reaching fully justified conclusions. For example, an indicator, such as a rising rate of unemployment, may be falsely assumed to reflect a failing program when it may actually be due to changing environmental conditions that are beyond the program’s control.

Sources

Sources of evidence in an evaluation may be people, documents, or observations. More than one source may be used to gather evidence for each indicator. In fact, selecting multiple sources provides an opportunity to include different perspectives about the program and enhances the evaluation’s credibility. For instance, an inside perspective may be reflected by internal documents and comments from staff or program managers; whereas clients and those who do not support the program may provide different, but equally relevant perspectives. Mixing these and other perspectives provides a more comprehensive view of the program or intervention.

The criteria used to select sources should be clearly stated so that users and other stakeholders can interpret the evidence accurately and assess if it may be biased. In addition, some sources provide information in narrative form (for example, a person’s experience when taking part in the program) and others are numerical (for example, how many people were involved in the program). The integration of qualitative and quantitative information can yield evidence that is more complete and more useful, thus meeting the needs and expectations of a wider range of stakeholders.

Quality

Quality refers to the appropriateness and integrity of information gathered in an evaluation. High quality data are reliable and informative. It is easier to collect if the indicators have been well defined. Other factors that affect quality may include instrument design, data collection procedures, training of those involved in data collection, source selection, coding, data management, and routine error checking. Obtaining quality data will entail tradeoffs (e.g. breadth vs. depth); stakeholders should decide together what is most important to them. Because all data have limitations, the intent of a practical evaluation is to strive for a level of quality that meets the stakeholders’ threshold for credibility.

Quantity

Quantity refers to the amount of evidence gathered in an evaluation. It is necessary to estimate in advance the amount of information that will be required and to establish criteria to decide when to stop collecting data – to know when enough is enough. Quantity affects the level of confidence or precision users can have – how sure we are that what we’ve learned is true. It also partly determines whether the evaluation will be able to detect effects. All evidence collected should have a clear, anticipated use.

Logistics

By logistics, we mean the methods, timing, and physical infrastructure for gathering and handling evidence. People and organizations also have cultural preferences that dictate acceptable ways of asking questions and collecting information, including who would be perceived as an appropriate person to ask the questions. For example, some participants may be unwilling to discuss their behavior with a stranger, whereas others are more at ease with someone they don’t know. Therefore, the techniques for gathering evidence in an evaluation must be in keeping with the cultural norms of the community. Data collection procedures should also ensure that confidentiality is protected.

Justify Conclusions

The process of justifying conclusions recognizes that evidence in an evaluation does not necessarily speak for itself. Evidence must be carefully considered from a number of different stakeholders’ perspectives to reach conclusions that are well -substantiated and justified. Conclusions become justified when they are linked to the evidence gathered and judged against agreed-upon values set by the stakeholders. Stakeholders must agree that conclusions are justified in order to use the evaluation results with confidence.

The principal elements involved in justifying conclusions based on evidence are:

Standards

Standards reflect the values held by stakeholders about the program. They provide the basis to make program judgments. The use of explicit standards for judgment is fundamental to sound evaluation. In practice, when stakeholders articulate and negotiate their values, these become the standards to judge whether a given program’s performance will, for instance, be considered “successful,” “adequate,” or “unsuccessful.”

Analysis and synthesis

Analysis and synthesis are methods to discover and summarize an evaluation’s findings. They are designed to detect patterns in evidence, either by isolating important findings (analysis) or by combining different sources of information to reach a larger understanding (synthesis). Mixed method evaluations require the separate analysis of each evidence element, as well as a synthesis of all sources to examine patterns that emerge. Deciphering facts from a given body of evidence involves deciding how to organize, classify, compare, and display information. These decisions are guided by the questions being asked, the types of data available, and especially by input from stakeholders and primary intended users.

Interpretation

Interpretation is the effort to figure out what the findings mean. Uncovering facts about a program’s performance isn’t enough to make conclusions. The facts must be interpreted to understand their practical significance. For example, saying, “15 % of the people in our area witnessed a violent act last year,” may be interpreted differently depending on the situation. For example, if 50% of community members had watched a violent act in the last year when they were surveyed five years ago, the group can suggest that, while still a problem, things are getting better in the community. However, if five years ago only 7% of those surveyed said the same thing, community organizations may see this as a sign that they might want to change what they are doing. In short, interpretations draw on information and perspectives that stakeholders bring to the evaluation. They can be strengthened through active participation or interaction with the data and preliminary explanations of what happened.

Judgements

Judgments are statements about the merit, worth, or significance of the program. They are formed by comparing the findings and their interpretations against one or more selected standards. Because multiple standards can be applied to a given program, stakeholders may reach different or even conflicting judgments. For instance, a program that increases its outreach by 10% from the previous year may be judged positively by program managers, based on standards of improved performance over time. Community members, however, may feel that despite improvements, a minimum threshold of access to services has still not been reached. Their judgment, based on standards of social equity, would therefore be negative. Conflicting claims about a program’s quality, value, or importance often indicate that stakeholders are using different standards or values in making judgments. This type of disagreement can be a catalyst to clarify values and to negotiate the appropriate basis (or bases) on which the program should be judged.

Recommendations

Recommendations are actions to consider as a result of the evaluation. Forming recommendations requires information beyond just what is necessary to form judgments. For example, knowing that a program is able to increase the services available to battered women doesn’t necessarily translate into a recommendation to continue the effort, particularly when there are competing priorities or other effective alternatives. Thus, recommendations about what to do with a given intervention go beyond judgments about a specific program’s effectiveness.

If recommendations aren’t supported by enough evidence, or if they aren’t in keeping with stakeholders’ values, they can really undermine an evaluation’s credibility. By contrast, an evaluation can be strengthened by recommendations that anticipate and react to what users will want to know.

Three things might increase the chances that recommendations will be relevant and well-received:

- Sharing draft recommendations

- Soliciting reactions from multiple stakeholders

- Presenting options instead of directive advice

Justifying conclusions in an evaluation is a process that involves different possible steps. For instance, conclusions could be strengthened by searching for alternative explanations from the ones you have chosen, and then showing why they are unsupported by the evidence. When there are different but equally well supported conclusions, each could be presented with a summary of their strengths and weaknesses. Techniques to analyze, synthesize, and interpret findings might be agreed upon before data collection begins.

Ensure Use and Share Lessons Learned

It is naive to assume that lessons learned in an evaluation will necessarily be used in decision making and subsequent action. Deliberate effort on the part of evaluators is needed to ensure that the evaluation findings will be used appropriately. Preparing for their use involves strategic thinking and continued vigilance in looking for opportunities to communicate and influence. Both of these should begin in the earliest stages of the process and continue throughout the evaluation.

The elements of key importance to be sure that the recommendations from an evaluation are used are:

Design

Design refers to how the evaluation’s questions, methods, and overall processes are constructed. As discussed in the third step of this framework (focusing the evaluation design), the evaluation should be organized from the start to achieve specific agreed-upon uses. Having a clear purpose that is focused on the use of what is learned helps those who will carry out the evaluation to know who will do what with the findings. Furthermore, the process of creating a clear design will highlight ways that stakeholders, through their many contributions, can improve the evaluation and facilitate the use of the results.

Preparation

Preparation refers to the steps taken to get ready for the future uses of the evaluation findings. The ability to translate new knowledge into appropriate action is a skill that can be strengthened through practice. In fact, building this skill can itself be a useful benefit of the evaluation. It is possible to prepare stakeholders for future use of the results by discussing how potential findings might affect decision making.

For example, primary intended users and other stakeholders could be given a set of hypothetical results and asked what decisions or actions they would make on the basis of this new knowledge. If they indicate that the evidence presented is incomplete or irrelevant and that no action would be taken, then this is an early warning sign that the planned evaluation should be modified. Preparing for use also gives stakeholders more time to explore both positive and negative implications of potential results and to identify different options for program improvement.

Feedback

Feedback is the communication that occurs among everyone involved in the evaluation. Giving and receiving feedback creates an atmosphere of trust among stakeholders; it keeps an evaluation on track by keeping everyone informed about how the evaluation is proceeding. Primary intended users and other stakeholders have a right to comment on evaluation decisions. From a standpoint of ensuring use, stakeholder feedback is a necessary part of every step in the evaluation. Obtaining valuable feedback can be encouraged by holding discussions during each step of the evaluation and routinely sharing interim findings, provisional interpretations, and draft reports.

Follow-up

Follow-up refers to the support that many users need during the evaluation and after they receive evaluation findings. Because of the amount of effort required, reaching justified conclusions in an evaluation can seem like an end in itself. It is not. Active follow-up may be necessary to remind users of the intended uses of what has been learned. Follow-up may also be required to stop lessons learned from becoming lost or ignored in the process of making complex or political decisions. To guard against such oversight, it may be helpful to have someone involved in the evaluation serve as an advocate for the evaluation’s findings during the decision -making phase.

Facilitating the use of evaluation findings also carries with it the responsibility to prevent misuse. Evaluation results are always bounded by the context in which the evaluation was conducted. Some stakeholders, however, may be tempted to take results out of context or to use them for different purposes than what they were developed for. For instance, over-generalizing the results from a single case study to make decisions that affect all sites in a national program is an example of misuse of a case study evaluation.

Similarly, program opponents may misuse results by overemphasizing negative findings without giving proper credit for what has worked. Active follow-up can help to prevent these and other forms of misuse by ensuring that evidence is only applied to the questions that were the central focus of the evaluation.

Dissemination

Dissemination is the process of communicating the procedures or the lessons learned from an evaluation to relevant audiences in a timely, unbiased, and consistent fashion. Like other elements of the evaluation, the reporting strategy should be discussed in advance with intended users and other stakeholders. Planning effective communications also requires considering the timing, style, tone, message source, vehicle, and format of information products. Regardless of how communications are constructed, the goal for dissemination is to achieve full disclosure and impartial reporting.

Along with the uses for evaluation findings, there are also uses that flow from the very process of evaluating. These “process uses” should be encouraged. The people who take part in an evaluation can experience profound changes in beliefs and behavior. For instance, an evaluation challenges staff members to act differently in what they are doing, and to question assumptions that connect program activities with intended effects.

Evaluation also prompts staff to clarify their understanding of the goals of the program. This greater clarity, in turn, helps staff members to better function as a team focused on a common end. In short, immersion in the logic, reasoning, and values of evaluation can have very positive effects, such as basing decisions on systematic judgments instead of on unfounded assumptions.

Additional process uses for evaluation include:

- By defining indicators, what really matters to stakeholders becomes clear

- It helps make outcomes matter by changing the reinforcements connected with achieving positive results. For example, a funder might offer “bonus grants” or “outcome dividends” to a program that has shown a significant amount of community change and improvement.

Standards for “good” evaluation

There are standards to assess whether all of the parts of an evaluation are well -designed and working to their greatest potential. The Joint Committee on Educational Evaluation developed “The Program Evaluation Standards” for this purpose. These standards, designed to assess evaluations of educational programs, are also relevant for programs and interventions related to community health and development.

The program evaluation standards make it practical to conduct sound and fair evaluations. They offer well-supported principles to follow when faced with having to make tradeoffs or compromises. Attending to the standards can guard against an imbalanced evaluation, such as one that is accurate and feasible, but isn’t very useful or sensitive to the context. Another example of an imbalanced evaluation is one that would be genuinely useful, but is impossible to carry out.

The following standards can be applied while developing an evaluation design and throughout the course of its implementation. Remember, the standards are written as guiding principles, not as rigid rules to be followed in all situations.

The 30 more specific standards are grouped into four categories:

- Utility

- Feasibility

- Propriety

- Accuracy

The utility standards are:

- Stakeholder Identification: People who are involved in (or will be affected by) the evaluation should be identified, so that their needs can be addressed.

- Evaluator Credibility: The people conducting the evaluation should be both trustworthy and competent, so that the evaluation will be generally accepted as credible or believable.

- Information Scope and Selection: Information collected should address pertinent questions about the program, and it should be responsive to the needs and interests of clients and other specified stakeholders.

- Values Identification: The perspectives, procedures, and rationale used to interpret the findings should be carefully described, so that the bases for judgments about merit and value are clear.

- Report Clarity: Evaluation reports should clearly describe the program being evaluated, including its context, and the purposes, procedures, and findings of the evaluation. This will help ensure that essential information is provided and easily understood.

- Report Timeliness and Dissemination: Significant midcourse findings and evaluation reports should be shared with intended users so that they can be used in a timely fashion.

- Evaluation Impact: Evaluations should be planned, conducted, and reported in ways that encourage follow-through by stakeholders, so that the evaluation will be used.

Feasibility Standards

The feasibility standards are to ensure that the evaluation makes sense – that the steps that are planned are both viable and pragmatic.

The feasibility standards are:

- Practical Procedures: The evaluation procedures should be practical, to keep disruption of everyday activities to a minimum while needed information is obtained.

- Political Viability: The evaluation should be planned and conducted with anticipation of the different positions or interests of various groups. This should help in obtaining their cooperation so that possible attempts by these groups to curtail evaluation operations or to misuse the results can be avoided or counteracted.

- Cost Effectiveness: The evaluation should be efficient and produce enough valuable information that the resources used can be justified.

Propriety Standards

The propriety standards ensure that the evaluation is an ethical one, conducted with regard for the rights and interests of those involved. The eight propriety standards follow.

- Service Orientation: Evaluations should be designed to help organizations effectively serve the needs of all of the targeted participants.

- Formal Agreements: The responsibilities in an evaluation (what is to be done, how, by whom, when) should be agreed to in writing, so that those involved are obligated to follow all conditions of the agreement, or to formally renegotiate it.

- Rights of Human Subjects: Evaluation should be designed and conducted to respect and protect the rights and welfare of human subjects, that is, all participants in the study.

- Human Interactions: Evaluators should respect basic human dignity and worth when working with other people in an evaluation, so that participants don’t feel threatened or harmed.

- Complete and Fair Assessment: The evaluation should be complete and fair in its examination, recording both strengths and weaknesses of the program being evaluated. This allows strengths to be built upon and problem areas addressed.

- Disclosure of Findings: The people working on the evaluation should ensure that all of the evaluation findings, along with the limitations of the evaluation, are accessible to everyone affected by the evaluation, and any others with expressed legal rights to receive the results.

- Conflict of Interest: Conflict of interest should be dealt with openly and honestly, so that it does not compromise the evaluation processes and results.

- Fiscal Responsibility: The evaluator’s use of resources should reflect sound accountability procedures and otherwise be prudent and ethically responsible, so that expenditures are accounted for and appropriate.

Accuracy Standards

The accuracy standards ensure that the evaluation findings are considered correct.

There are 12 accuracy standards:

- Program Documentation: The program should be described and documented clearly and accurately, so that what is being evaluated is clearly identified.

- Context Analysis: The context in which the program exists should be thoroughly examined so that likely influences on the program can be identified.

- Described Purposes and Procedures: The purposes and procedures of the evaluation should be monitored and described in enough detail that they can be identified and assessed.

- Defensible Information Sources: The sources of information used in a program evaluation should be described in enough detail that the adequacy of the information can be assessed.

- Valid Information: The information gathering procedures should be chosen or developed and then implemented in such a way that they will assure that the interpretation arrived at is valid.

- Reliable Information: The information gathering procedures should be chosen or developed and then implemented so that they will assure that the information obtained is sufficiently reliable.

- Systematic Information: The information from an evaluation should be systematically reviewed and any errors found should be corrected.

- Analysis of Quantitative Information: Quantitative information – data from observations or surveys – in an evaluation should be appropriately and systematically analyzed so that evaluation questions are effectively answered.

- Analysis of Qualitative Information: Qualitative information – descriptive information from interviews and other sources – in an evaluation should be appropriately and systematically analyzed so that evaluation questions are effectively answered.

- Justified Conclusions: The conclusions reached in an evaluation should be explicitly justified, so that stakeholders can understand their worth.

- Impartial Reporting: Reporting procedures should guard against the distortion caused by personal feelings and biases of people involved in the evaluation, so that evaluation reports fairly reflect the evaluation findings.

- Metaevaluation: The evaluation itself should be evaluated against these and other pertinent standards, so that it is appropriately guided and, on completion, stakeholders can closely examine its strengths and weaknesses.

Applying the framework: Conducting optimal evaluations

There is an ever-increasing agreement on the worth of evaluation; in fact, doing so is often required by funders and other constituents. So, community health and development professionals can no longer question whether or not to evaluate their programs. Instead, the appropriate questions are:

- What is the best way to evaluate?

- What are we learning from the evaluation?

- How will we use what we learn to become more effective?

The framework for program evaluation helps answer these questions by guiding users to select evaluation strategies that are useful, feasible, proper, and accurate.

To use this framework requires quite a bit of skill in program evaluation. In most cases there are multiple stakeholders to consider, the political context may be divisive, steps don’t always follow a logical order, and limited resources may make it difficult to take a preferred course of action. An evaluator’s challenge is to devise an optimal strategy, given the conditions she is working under. An optimal strategy is one that accomplishes each step in the framework in a way that takes into account the program context and is able to meet or exceed the relevant standards.

This framework also makes it possible to respond to common concerns about program evaluation. For instance, many evaluations are not undertaken because they are seen as being too expensive. The cost of an evaluation, however, is relative; it depends upon the question being asked and the level of certainty desired for the answer. A simple, low-cost evaluation can deliver information valuable for understanding and improvement.

Rather than discounting evaluations as a time-consuming sideline, the framework encourages evaluations that are timed strategically to provide necessary feedback. This makes it possible to make evaluation closely linked with everyday practices.

Another concern centers on the perceived technical demands of designing and conducting an evaluation. However, the practical approach endorsed by this framework focuses on questions that can improve the program.

Finally, the prospect of evaluation troubles many staff members because they perceive evaluation methods as punishing (“They just want to show what we’re doing wrong.”), exclusionary (“Why aren’t we part of it? We’re the ones who know what’s going on.”), and adversarial (“It’s us against them.”) The framework instead encourages an evaluation approach that is designed to be helpful and engages all interested stakeholders in a process that welcomes their participation.

In Summary

Evaluation is a powerful strategy for distinguishing programs and interventions that make a difference from those that don’t. It is a driving force for developing and adapting sound strategies, improving existing programs, and demonstrating the results of investments in time and other resources. It also helps determine if what is being done is worth the cost.

This recommended framework for program evaluation is both a synthesis of existing best practices and a set of standards for further improvement. It supports a practical approach to evaluation based on steps and standards that can be applied in almost any setting. Because the framework is purposefully general, it provides a stable guide to design and conduct a wide range of evaluation efforts in a variety of specific program areas. The framework can be used as a template to create useful evaluation plans to contribute to understanding and improvement. The Magenta Book – Guidance for Evaluation provides additional information on requirements for good evaluation, and some straightforward steps to make a good evaluation of an intervention more feasible, read The Magenta Book – Guidance for Evaluation.

Online Resources

Are You Ready to Evaluate your Coalition? prompts 15 questions to help the group decide whether your coalition is ready to evaluate itself and its work.

The American Evaluation Association Guiding Principles for Evaluators helps guide evaluators in their professional practice.

CDC Evaluation Resources provides a list of resources for evaluation, as well as links to professional associations and journals.

Chapter 11: Community Interventions in the “Introduction to Community Psychology” explains professionally-led versus grassroots interventions, what it means for a community intervention to be effective, why a community needs to be ready for an intervention, and the steps to implementing community interventions.

The Comprehensive Cancer Control Branch Program Evaluation Toolkit is designed to help grantees plan and implement evaluations of their NCCCP-funded programs, this toolkit provides general guidance on evaluation principles and techniques, as well as practical templates and tools.

Developing an Effective Evaluation Plan is a workbook provided by the CDC. In addition to information on designing an evaluation plan, this book also provides worksheets as a step-by-step guide.

EvaluACTION, from the CDC, is designed for people interested in learning about program evaluation and how to apply it to their work. Evaluation is a process, one dependent on what you’re currently doing and on the direction in which you’d like go. In addition to providing helpful information, the site also features an interactive Evaluation Plan & Logic Model Builder, so you can create customized tools for your organization to use.

Evaluating Your Community-Based Program is a handbook designed by the American Academy of Pediatrics covering a variety of topics related to evaluation.

GAO Designing Evaluations is a handbook provided by the U.S. Government Accountability Office with copious information regarding program evaluations.

The CDC’s Introduction to Program Evaluation for Publilc Health Programs: A Self-Study Guide is a “how-to” guide for planning and implementing evaluation activities. The manual, based on CDC’s Framework for Program Evaluation in Public Health, is intended to assist with planning, designing, implementing and using comprehensive evaluations in a practical way.

McCormick Foundation Evaluation Guide is a guide to planning an organization’s evaluation, with several chapters dedicated to gathering information and using it to improve the organization.

A Participatory Model for Evaluating Social Programs from the James Irvine Foundation.

Practical Evaluation for Public Managers is a guide to evaluation written by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Penn State Program Evaluation offers information on collecting different forms of data and how to measure different community markers.

Program Evaluaton information page from Implementation Matters.

The Program Manager’s Guide to Evaluation is a handbook provided by the Administration for Children and Families with detailed answers to nine big questions regarding program evaluation.

Program Planning and Evaluation is a website created by the University of Arizona. It provides links to information on several topics including methods, funding, types of evaluation, and reporting impacts.

User-Friendly Handbook for Program Evaluation is a guide to evaluations provided by the National Science Foundation. This guide includes practical information on quantitative and qualitative methodologies in evaluations.

W.K. Kellogg Foundation Evaluation Handbook provides a framework for thinking about evaluation as a relevant and useful program tool. It was originally written for program directors with direct responsibility for the ongoing evaluation of the W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

Print Resources

This Community Tool Box section is an edited version of:

CDC Evaluation Working Group. (1999). (Draft). Recommended framework for program evaluation in public health practice. Atlanta, GA: Author.

The article cites the following references:

Adler. M., & Ziglio, E. (1996). Gazing into the oracle: the delphi method and its application to social policy and community health and development. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Barrett, F. Program Evaluation: A Step-by-Step Guide. Sunnycrest Press, 2013. This practical manual includes helpful tips to develop evaluations, tables illustrating evaluation approaches, evaluation planning and reporting templates, and resources if you want more information.

Basch, C., Silepcevich, E., Gold, R., Duncan, D., & Kolbe, L. (1985). Avoiding type III errors in health education program evaluation: a case study. Health Education Quarterly. 12(4):315-31.

Bickman L, & Rog, D. (1998). Handbook of applied social research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Boruch, R. (1998). Randomized controlled experiments for evaluation and planning. In Handbook of applied social research methods, edited by Bickman L., & Rog. D. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications: 161-92.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention DoHAP. Evaluating CDC HIV prevention programs: guidance and data system. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, 1999.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for evaluating surveillance systems. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 1988;37(S-5):1-18.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Handbook for evaluating HIV education. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Adolescent and School Health, 1995.

Cook, T., & Campbell, D. (1979). Quasi-experimentation. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

Cook, T.,& Reichardt, C. (1979). Qualitative and quantitative methods in evaluation research. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Cousins, J.,& Whitmore, E. (1998). Framing participatory evaluation. In Understanding and practicing participatory evaluation, vol. 80, edited by E Whitmore. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass: 5-24.

Chen, H. (1990). Theory driven evaluations. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

de Vries, H., Weijts, W., Dijkstra, M., & Kok, G. (1992). The utilization of qualitative and quantitative data for health education program planning, implementation, and evaluation: a spiral approach. Health Education Quarterly.1992; 19(1):101-15.

Dyal, W. (1995). Ten organizational practices of community health and development: a historical perspective. American Journal of Preventive Medicine;11(6):6-8.

Eddy, D. (1998).Performance measurement: problems and solutions. Health Affairs;17 (4):7-25.Harvard Family Research Project. Performance measurement. In The Evaluation Exchange, vol. 4, 1998, pp. 1-15.

Eoyang,G., & Berkas, T. (1996). Evaluation in a complex adaptive system. Edited by (we don´t have the names), (1999): Taylor-Powell E, Steele S, Douglah M. Planning a program evaluation. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension.

Fawcett, S.B., Paine-Andrews, A., Fancisco, V.T., Schultz, J.A., Richter, K.P, Berkley-Patton, J., Fisher, J., Lewis, R.K., Lopez, C.M., Russos, S., Williams, E.L., Harris, K.J., & Evensen, P. (2001). Evaluating community initiatives for health and development. In I. Rootman, D. McQueen, et al. (Eds.), Evaluating health promotion approaches. (pp. 241-277). Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization – Europe.

Fawcett , S., Sterling, T., Paine-, A., Harris, K., Francisco, V. et al. (1996). Evaluating community efforts to prevent cardiovascular diseases. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

Fetterman, D.,, Kaftarian, S., & Wandersman, A. (1996). Empowerment evaluation: knowledge and tools for self-assessment and accountability. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Frechtling, J.,& Sharp, L. (1997). User-friendly handbook for mixed method evaluations. Washington, DC: National Science Foundation.

Goodman, R., Speers, M., McLeroy, K., Fawcett, S., Kegler M., et al. (1998). Identifying and defining the dimensions of community capacity to provide a basis for measurement. Health Education and Behavior;25(3):258-78.

Greene, J. (1994). Qualitative program evaluation: practice and promise. In Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by NK Denzin and YS Lincoln. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Haddix, A., Teutsch. S., Shaffer. P., & Dunet. D. (1996). Prevention effectiveness: a guide to decision analysis and economic evaluation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hennessy, M. Evaluation. In Statistics in Community health and development, edited by Stroup. D.,& Teutsch. S. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1998: 193-219

Henry, G. (1998). Graphing data. In Handbook of applied social research methods, edited by Bickman. L., & Rog. D.. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications: 527-56.

Henry, G. (1998). Practical sampling. In Handbook of applied social research methods, edited by Bickman. L., & Rog. D.. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications: 101-26.

Institute of Medicine. Improving health in the community: a role for performance monitoring. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1997.

Joint Committee on Educational Evaluation, James R. Sanders (Chair). The program evaluation standards: how to assess evaluations of educational programs. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1994.

Kaplan, R., & Norton, D. The balanced scorecard: measures that drive performance. Harvard Business Review 1992;Jan-Feb71-9.

Kar, S. (1989). Health promotion indicators and actions. New York, NY: Springer Publications.

Knauft, E. (1993). What independent sector learned from an evaluation of its own hard-to -measure programs. In A vision of evaluation, edited by ST Gray. Washington, DC: Independent Sector.

Koplan, J. (1999) CDC sets millennium priorities. US Medicine 4-7.

Lipsy, M. (1998). Design sensitivity: statistical power for applied experimental research. In Handbook of applied social research methods, edited by Bickman, L., & Rog, D. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. 39-68.

Lipsey, M. (1993). Theory as method: small theories of treatments. New Directions for Program Evaluation;(57):5-38.

Lipsey, M. (1997). What can you build with thousands of bricks? Musings on the cumulation of knowledge in program evaluation. New Directions for Evaluation; (76): 7-23.

Love, A. (1991). Internal evaluation: building organizations from within. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Miles, M., & Huberman, A. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: a sourcebook of methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

National Quality Program. (1999). National Quality Program, vol. 1999. National Institute of Standards and Technology.

National Quality Program. Baldridge index outperforms S&P 500 for fifth year, vol. 1999.

National Quality Program, 1999.

National Quality Program. Health care criteria for performance excellence, vol. 1999. National Quality Program, 1998.

Newcomer, K. Using statistics appropriately. In Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation, edited by Wholey,J., Hatry, H., & Newcomer. K. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1994: 389-416.

Patton, M. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Patton, M (1997). Toward distinguishing empowerment evaluation and placing it in a larger context. Evaluation Practice;18(2):147-63.

Patton, M. (1997). Utilization-focused evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Perrin, B. Effective use and misuse of performance measurement. American Journal of Evaluation 1998;19(3):367-79.

Perrin, E, Koshel J. (1997). Assessment of performance measures for community health and development, substance abuse, and mental health. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Phillips, J. (1997). Handbook of training evaluation and measurement methods. Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing Company.

Poreteous, N., Sheldrick B., & Stewart P. (1997). Program evaluation tool kit: a blueprint for community health and development management. Ottawa, Canada: Community health and development Research, Education, and Development Program, Ottawa-Carleton Health Department.

Posavac, E., & Carey R. (1980). Program evaluation: methods and case studies. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Preskill, H. & Torres R. (1998). Evaluative inquiry for learning in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Public Health Functions Project. (1996). The public health workforce: an agenda for the 21st century. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Community health and development Service.

Public Health Training Network. (1998). Practical evaluation of public health programs. CDC, Atlanta, GA.

Reichardt, C., & Mark M. (1998). Quasi-experimentation. In Handbook of applied social research methods, edited by L Bickman and DJ Rog. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 193-228.

Rossi, P., & Freeman H. (1993). Evaluation: a systematic approach. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Rush, B., & Ogbourne A. (1995). Program logic models: expanding their role and structure for program planning and evaluation. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation;695 -106.

Sanders, J. (1993). Uses of evaluation as a means toward organizational effectiveness. In A vision of evaluation, edited by ST Gray. Washington, DC: Independent Sector.

Schorr, L. (1997). Common purpose: strengthening families and neighborhoods to rebuild America. New York, NY: Anchor Books, Doubleday.

Scriven, M. (1998). A minimalist theory of evaluation: the least theory that practice requires. American Journal of Evaluation.

Shadish, W., Cook, T., Leviton, L. (1991). Foundations of program evaluation. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Shadish, W. (1998). Evaluation theory is who we are. American Journal of Evaluation:19(1):1-19.

Shulha, L., & Cousins, J. (1997). Evaluation use: theory, research, and practice since 1986. Evaluation Practice.18(3):195-208

Sieber, J. (1998). Planning ethically responsible research. In Handbook of applied social research methods, edited by L Bickman and DJ Rog. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications: 127-56.

Steckler, A., McLeroy, K., Goodman, R., Bird, S., McCormick, L. (1992). Toward integrating qualitative and quantitative methods: an introduction. Health Education Quarterly;191-8.

Taylor-Powell, E., Rossing, B., Geran, J. (1998). Evaluating collaboratives: reaching the potential. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension.

Teutsch, S. A framework for assessing the effectiveness of disease and injury prevention. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Recommendations and Reports Series 1992;41 (RR-3 (March 27, 1992):1-13.

Torres, R., Preskill, H., Piontek, M., (1996). Evaluation strategies for communicating and reporting: enhancing learning in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Trochim, W. (1999). Research methods knowledge base, vol.

United Way of America. Measuring program outcomes: a practical approach. Alexandria, VA: United Way of America, 1996.

U.S. General Accounting Office. Case study evaluations. GAO/PEMD-91-10.1.9. Washington, DC: U.S. General Accounting Office, 1990.