10 Using Images

Using Accessible Images

In this section, we provide recommendations to guide your inclusion of accessible, image-based content.[1]

What are images?

For the purposes of this discussion, we define images as non-text elements that include photographs, illustrations, diagrams, pictures, charts, graphs, and maps.

File types used: GIF, JPG, PNG

Who are you doing this for?

This work supports students who:

- Are blind or have low vision

- Have poor contrast vision

- Are color blind and cannot differentiate between certain colors

- Use a device with monochrome display

- Use a print copy that is in black and white

- Have limited Internet access and cannot download images

- Have a form of cognitive disability

What do you need to do?

Before you can determine what to do to make an image accessible, you must identify its purpose or value to your textbook. Consider the following questions:

- Does your image serve a functional purpose? In other words, is it conveying non-text content to students?

- Or does your image serve more of a decorative purpose? In other words, is it primarily a design element that does not convey content?

Functional images

Consider what your content page would look like if the images didn’t load. Now try writing alternative text for each image that would work as a replacement and provide the same information as the image.

There are three ways to provide alternative text descriptions for images:

- Describe the image in the surrounding text.

- Describe the image in the alt tag.

- Create and link to a long description of the image.

As you work on developing your alternative text descriptions, keep the following recommendations and guidelines in mind:

- Remember that alternative text must convey the purpose and function of an image and is rarely a literal description of the image (e.g., “photo of cat”). Rather than providing what the image looks like, alternative text should convey the content of the image and what it does. This means that the same image may need different alt-text depending on how it’s used. [2]

- For relatively simple images (e.g., photographs, illustrations), try to keep your text descriptions short, like a Tweet. You should aim to create a brief alternative (one or two short sentences) that is an accurate and concise equivalent to the information in the image.

- For more complex images (e.g., detailed charts, graphs, maps), you will need to provide more than a one- or two-sentence description to ensure all users will benefit from the content or context you intend to provide.

- Leave out unnecessary information. For example, you do not need to include information like “image of…” or “photo of…”; assistive technologies will automatically identify the material as an image, so including that detail in your alternative description is redundant.

- Avoid redundancy of content in your alternative description. Don’t repeat information that already appears in text adjacent to the image.

Descriptions in surrounding text

You can use the surrounding text to provide the same information as conveyed by the image. This is often the best option for complex images because it makes the information available for everyone, not just those using the alt tags.

If you are editing someone else’s work for accessibility, you are probably not at liberty to start adding to the main text. However, if you are the author, this is the best and easiest option.

If an image has been adequately described in the surrounding text, you can either provide a few-word description of the image in the alt tag or follow the procedures for decorative images.

Example language in a textbook with an image described in the surrounding text:

Many older buildings in rural areas have infrastructure problems and are simply using workarounds until they can secure needed funds to adequately fix the problem. As you can see from the image below, this building in Virginia has visible cracks in the bricks and the wall is being reinforced with timber for added protection.

Alt tags

An alt tag refers to the alt attribute (alt is short for alternative) within an IMG tag. All images uploaded into Pressbooks have an alt tag, but for them to be useful, you need to insert an image description.

Alt tags are used in two cases:

- When an image doesn’t download due slow Internet, the alt tag content will display instead of the image.

- For people who are visually impaired and use screen readers, when a screen reader finds an image, it will read out the content of the alt tag.

Alt tags should be no longer than 125 characters, including spaces and punctuation.[3]

Example language in a textbook with an image described in the alt-tag:

NOTE: the alt-tags are only visible if you’re using a screen reader or inspect the HTML. In the example below, the text above the photo does not describe the image but the alt-text does.

Many older buildings in rural areas have infrastructure problems and are simply using workarounds until they can secure needed funds to adequately fix the problem.

Long descriptions

Complex images, especially charts or graphs, will often require descriptions longer than 125 characters and it may not always be possible to add an explanation to the surrounding text. In this case, you can provide a link to a longer image description or an accessible table. One way to do this is to create a section for long descriptions in your resource and use links to allow people to easily switch between the image and its description and back again.

Using color

Consider what your images would look like if they only displayed in black and white. Would any necessary context or content be lost if the color was “turned off?” Images should not rely on color as the only means of conveying information. If your point requires color, you may need to edit or format the image so the concepts presented are not lost to those who are color blind or require high contrast between colors.

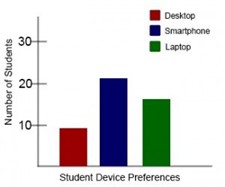

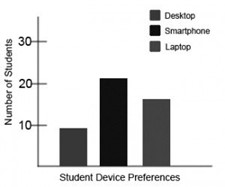

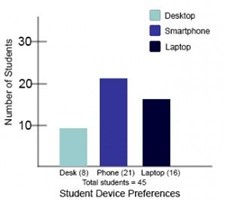

Example 1: Inaccessible bar chart. In Chart 1, color is the only means by which information is conveyed. For students who are color blind, have poor contrast vision, or are using a black-and-white print copy (see Chart 2), relevant information is lost.

Example 2: Accessible bar chart. Students who are color blind can distinguish between high-contrast shades. In Chart 3, contextual labels have been added to each bar at the bottom of the chart. Note that the chart will still require an alt tag.

Decorative images

If an image does not add meaning, i.e., if it’s included for decorative or design purposes only, or if the image is adequately described in the caption and/or surrounding text, it doesn’t need an alt tag. Including alternative text descriptions for decorative images “simply slows the process down with no benefit because the screen-reading software vocalizes the content of the [alternative text description], whether that alternative text adds value or not.”[4]

However, this doesn’t mean that you should leave an alt tag blank.

When a screen reader detects an image with a blank alt tag, it will read out the image file location. When an image doesn’t require an alt tag, place two double-quotation marks (“”) in the Alternative Text field; this step will prompt the screen reader to say “Graphic” and move on to the caption.

- Adapted from BC Open Textbook Accessibility Toolkit. Authored by Amanda Coolidge, Sue Doner, and Tara Robertson. Provided by BCCampus. Located at https://opentextbc.ca/accessibilitytoolkit/. Licensed under CC BY: Attribution ↵

- Enter yo• “Alt text blunders," WebAIM, accessed March 27, 2018, http://webaim.org/articles/gonewild/#alttext.ur footnote content here. ↵

- All screen readers are different, so a 125-character max is a recommendation. Other sources may provide a different number. This is because when a screen reader finds an image, it will say “Graphic” before reading out the alt tag. If the alt tag is longer than 125 characters, the screen reader will interrupt the flow of text and say “Graphic” again, before continuing to read out the alt tag. This can be confusing. For images that require descriptions longer than 125 characters, see the section on long descriptions. ↵

- "Top 10 Tips for Making Your Website Accessible," UC Berkeley: Web Access, accessed March 27, 2018, https://webaccess.berkeley.edu/resources/tips/web-accessibility#accessible-alt. ↵