191 23.12 RLC Series AC Circuits

Summary

- Calculate the impedance, phase angle, resonant frequency, power, power factor, voltage, and/or current in a RLC series circuit.

- Draw the circuit diagram for an RLC series circuit.

- Explain the significance of the resonant frequency.

Impedance

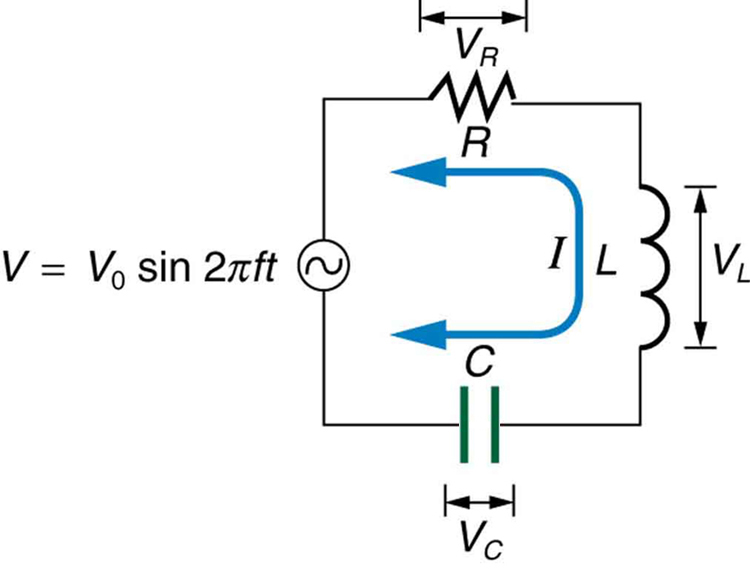

When alone in an AC circuit, inductors, capacitors, and resistors all impede current. How do they behave when all three occur together? Interestingly, their individual resistances in ohms do not simply add. Because inductors and capacitors behave in opposite ways, they partially to totally cancel each other’s effect. Figure 1 shows an RLC series circuit with an AC voltage source, the behavior of which is the subject of this section. The crux of the analysis of an RLC circuit is the frequency dependence of $latex \boldsymbol{X_L} $ and $latex \boldsymbol{X_C} $, and the effect they have on the phase of voltage versus current (established in the preceding section). These give rise to the frequency dependence of the circuit, with important “resonance” features that are the basis of many applications, such as radio tuners.

The combined effect of resistance $latex \boldsymbol{R} $, inductive reactance $latex \boldsymbol{X_L} $, and capacitive reactance $latex \boldsymbol{X_C} $ is defined to be impedance, an AC analogue to resistance in a DC circuit. Current, voltage, and impedance in an RLC circuit are related by an AC version of Ohm’s law:

Here $latex \boldsymbol{I_0} $ is the peak current, $latex \boldsymbol{V_0} $ the peak source voltage, and $latex \boldsymbol{Z} $ is the impedance of the circuit. The units of impedance are ohms, and its effect on the circuit is as you might expect: the greater the impedance, the smaller the current. To get an expression for $latex \boldsymbol{Z} $ in terms of $latex \boldsymbol{R} $, $latex \boldsymbol{X_L} $, and $latex \boldsymbol{X_C} $, we will now examine how the voltages across the various components are related to the source voltage. Those voltages are labeled $latex \boldsymbol{V_R} $, $latex \boldsymbol{V_L} $, and $latex \boldsymbol{V_C} $ in Figure 1.

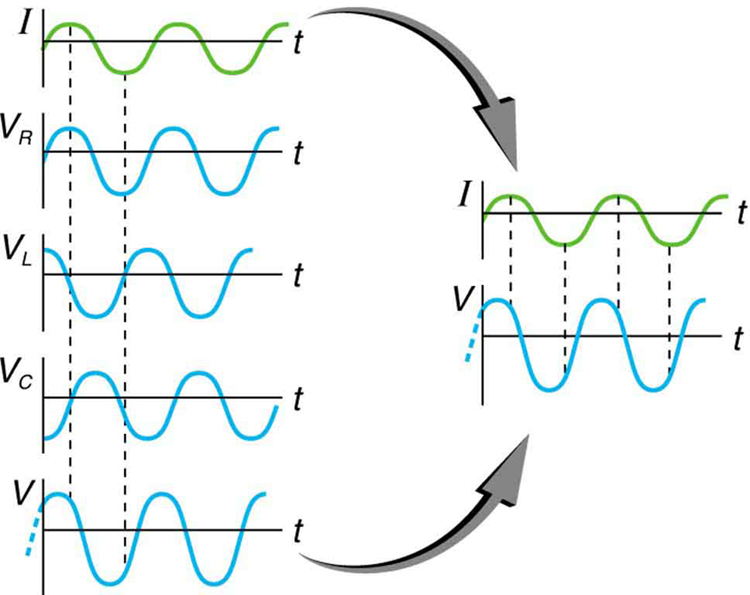

Conservation of charge requires current to be the same in each part of the circuit at all times, so that we can say the currents in $latex \boldsymbol{R} $, $latex \boldsymbol{L} $, and $latex \boldsymbol{C} $ are equal and in phase. But we know from the preceding section that the voltage across the inductor $latex \boldsymbol{V_L} $ leads the current by one-fourth of a cycle, the voltage across the capacitor $latex \boldsymbol{V_C} $ follows the current by one-fourth of a cycle, and the voltage across the resistor $latex \boldsymbol{V_R} $ is exactly in phase with the current. Figure 2 shows these relationships in one graph, as well as showing the total voltage around the circuit $latex \boldsymbol{V = V_R + V_L + V_C} $, where all four voltages are the instantaneous values. According to Kirchhoff’s loop rule, the total voltage around the circuit VV is also the voltage of the source.

You can see from Figure 2 that while $latex \boldsymbol{V_R} $ is in phase with the current, $latex \boldsymbol{V_L} $ leads by $latex \boldsymbol{90^{\circ}} $, and $latex \boldsymbol{V_C} $ follows by $latex \boldsymbol{90^{\circ}} $. Thus $latex \boldsymbol{V_L} $ and $latex \boldsymbol{V_C} $ are $latex \boldsymbol{180^{\circ}} $ out of phase (crest to trough) and tend to cancel, although not completely unless they have the same magnitude. Since the peak voltages are not aligned (not in phase), the peak voltage $latex \boldsymbol{V_0} $ of the source does not equal the sum of the peak voltages across $latex \boldsymbol{R} $, $latex \boldsymbol{L} $, and $latex \boldsymbol{C} $. The actual relationship is

where $latex \boldsymbol{V_{0R}} $, $latex \boldsymbol{V_{0L}} $, and $latex \boldsymbol{V_{0C}} $ are the peak voltages across $latex \boldsymbol{R} $, $latex \boldsymbol{L} $, and $latex \boldsymbol{C} $, respectively. Now, using Ohm’s law and definitions from Chapter 23.11 Reactance, Inductive and Capacitive, we substitute $latex \boldsymbol{V_0 = I_0Z} $ into the above, as well as $latex \boldsymbol{V_{0R} = I_0R} $, $latex \boldsymbol{V_{0L} = I_0X_L} $ and $latex \boldsymbol{V_{0C} = I_0X_C} $, yielding

$latex \boldsymbol{I_0} $ cancels to yield an expression for $latex \boldsymbol{Z} $:

which is the impedance of an RLC series AC circuit. For circuits without a resistor, take $latex \boldsymbol{R = 0} $; for those without an inductor, take $latex \boldsymbol{X_L = 0} $; and for those without a capacitor, take $latex \boldsymbol{X_C = 0} $.

Example 1: Calculating Impedance and Current

An RLC series circuit has a $latex \boldsymbol{40.0 \;\Omega} $ resistor, a 3.00 mH inductor, and a $latex \boldsymbol{5.00 \;\mu F} $ capacitor. (a) Find the circuit’s impedance at 60.0 Hz and 10.0 kHz, noting that these frequencies and the values for $latex \boldsymbol{L} $ and $latex \boldsymbol{C} $ are the same as in Chapter 23.11 Example 1 and Chapter 23.11 Example 2. (b) If the voltage source has $latex \boldsymbol{V_{\textbf{rms}} = 120 \;\textbf{V}} $, what is $latex \boldsymbol{I_{\textbf{rms}}} $ at each frequency?

Strategy

For each frequency, we use $latex \boldsymbol{Z = \sqrt{R^2 + (X_L – X_C)^2}} $ to find the impedance and then Ohm’s law to find current. We can take advantage of the results of the previous two examples rather than calculate the reactances again.

Solution for (a)

At 60.0 Hz, the values of the reactances were found in Chapter 23.11 Example 1 to be $latex \boldsymbol{X_L = 1.13 \;\Omega} $ and in Chapter 23.11 Example 2 to be $latex \boldsymbol{X_C = 531 \;\Omega} $. Entering these and the given $latex \boldsymbol{40.0 \;\Omega} $ for resistance into $latex \boldsymbol{Z = \sqrt{R^2 + (X_L – X_C)^2}} $ yields

Similarly, at 10.0 kHz, $latex \boldsymbol{X_L = 188 \;\Omega} $ and $latex \boldsymbol{X_C = 3.18 \;\Omega} $, so that

Discussion for (a)

In both cases, the result is nearly the same as the largest value, and the impedance is definitely not the sum of the individual values. It is clear that $latex \boldsymbol{X_L} $ dominates at high frequency and $latex \boldsymbol{X_C} $ dominates at low frequency.

Solution for (b)

The current $latex \boldsymbol{I_{\textbf{rms}}} $ can be found using the AC version of Ohm’s law in Equation $latex \boldsymbol{I_{rms} = V_{rms} / Z} $:

Finally, at 10.0 kHz, we find

at 10.0 kHz

Discussion for (a)

The current at 60.0 Hz is the same (to three digits) as found for the capacitor alone in Example 1. The capacitor dominates at low frequency. The current at 10.0 kHz is only slightly different from that found for the inductor alone in Chapter 23.11 Example 1. The inductor dominates at high frequency.

Resonance in RLC Series AC Circuits

How does an RLC circuit behave as a function of the frequency of the driving voltage source? Combining Ohm’s law, $latex \boldsymbol{I_{\textbf{rms}} = V_{\textbf{rms}}/Z} $, and the expression for impedance $latex \boldsymbol{Z} $ from $latex \boldsymbol{Z = \sqrt{R^2 + (X_L-X_C)^2}} $ gives

The reactances vary with frequency, with $latex \boldsymbol{X_L} $ large at high frequencies and $latex \boldsymbol{X_C} $ large at low frequencies, as we have seen in three previous examples. At some intermediate frequency $latex \boldsymbol{f_0} $, the reactances will be equal and cancel, giving $latex \boldsymbol{Z = R} $ —this is a minimum value for impedance, and a maximum value for $latex \boldsymbol{I_{\textbf{rms}}} $ results. We can get an expression for $latex \boldsymbol{f_0} $ by taking

Substituting the definitions of $latex \boldsymbol{X_L} $ and $latex \boldsymbol{X_C} $,

Solving this expression for $latex \boldsymbol{f_0} $ yields

where $latex \boldsymbol{f_0} $ is the resonant frequency of an RLC series circuit. This is also the natural frequency at which the circuit would oscillate if not driven by the voltage source. At $latex \boldsymbol{f_0} $, the effects of the inductor and capacitor cancel, so that $latex \boldsymbol{Z = R} $, and $latex \boldsymbol{I_{\textbf{rms}}} $ is a maximum.

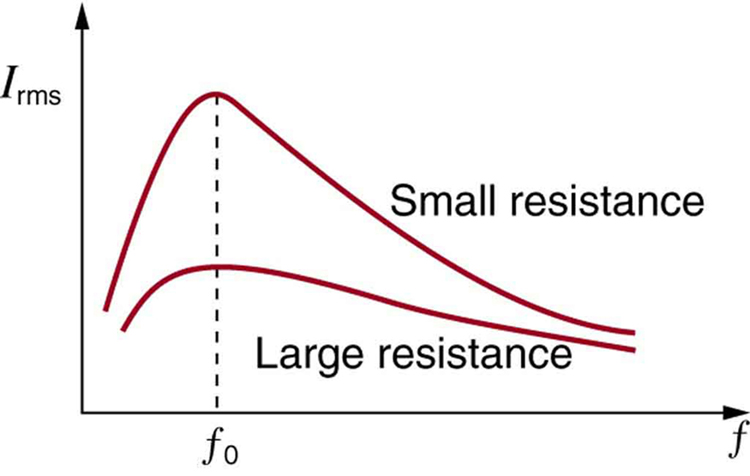

Resonance in AC circuits is analogous to mechanical resonance, where resonance is defined to be a forced oscillation—in this case, forced by the voltage source—at the natural frequency of the system. The receiver in a radio is an RLC circuit that oscillates best at its $latex \boldsymbol{f_0} $. A variable capacitor is often used to adjust $latex \boldsymbol{f_0} $ to receive a desired frequency and to reject others. Figure 3 is a graph of current as a function of frequency, illustrating a resonant peak in $latex \boldsymbol{I_{\textbf{rms}}} $ at $latex \boldsymbol{f_0} $. The two curves are for two different circuits, which differ only in the amount of resistance in them. The peak is lower and broader for the higher-resistance circuit. Thus the higher-resistance circuit does not resonate as strongly and would not be as selective in a radio receiver, for example.

Example 2: Calculating Resonant Frequency and Current

For the same RLC series circuit having a $latex \boldsymbol{40.0 \;\Omega} $ resistor, a 3.00 mH inductor, and a $latex \boldsymbol{5.00 \;\mu F} $ capacitor: (a) Find the resonant frequency. (b) Calculate $latex \boldsymbol{I_{\textbf{rms}}} $ at resonance if $latex \boldsymbol{V_{\textbf{rms}}} $ is 120 V.

Strategy

The resonant frequency is found by using the expression in $latex \boldsymbol{f_0 = \frac{1}{2 \pi \sqrt{LC}}} $. The current at that frequency is the same as if the resistor alone were in the circuit.

Solution for (a)

Entering the given values for $latex \boldsymbol{L} $ and $latex \boldsymbol{C} $ into the expression given for $latex \boldsymbol{f_0} $ in $latex \boldsymbol{f_0 = \frac{1}{2 \pi \sqrt{LC}}} $ yields

Discussion for (a)

We see that the resonant frequency is between 60.0 Hz and 10.0 kHz, the two frequencies chosen in earlier examples. This was to be expected, since the capacitor dominated at the low frequency and the inductor dominated at the high frequency. Their effects are the same at this intermediate frequency.

Solution for (b)

The current is given by Ohm’s law. At resonance, the two reactances are equal and cancel, so that the impedance equals the resistance alone. Thus,

Discussion for (b)

At resonance, the current is greater than at the higher and lower frequencies considered for the same circuit in the preceding example.

Power in RLC Series AC Circuits

If current varies with frequency in an RLC circuit, then the power delivered to it also varies with frequency. But the average power is not simply current times voltage, as it is in purely resistive circuits. As was seen in Figure 2, voltage and current are out of phase in an RLC circuit. There is a phase angle $latex \boldsymbol{\phi} $ between the source voltage $latex \boldsymbol{V} $ and the current $latex \boldsymbol{I} $, which can be found from

For example, at the resonant frequency or in a purely resistive circuit $latex \boldsymbol{Z = R} $, so that $latex \boldsymbol{\textbf{cos} \;\phi = 1} $. This implies that $latex \boldsymbol{\phi = 0^{\circ}} $ and that voltage and current are in phase, as expected for resistors. At other frequencies, average power is less than at resonance. This is both because voltage and current are out of phase and because $latex \boldsymbol{I_{\textbf{rms}}} $ is lower. The fact that source voltage and current are out of phase affects the power delivered to the circuit. It can be shown that the average power is

Thus $latex \boldsymbol{\textbf{cos} \;\phi} $ is called the power factor, which can range from 0 to 1. Power factors near 1 are desirable when designing an efficient motor, for example. At the resonant frequency, $latex \boldsymbol{\textbf{cos} \;\phi = 1} $.

Example 3: Calculating the Power Factor and Power

For the same RLC series circuit having a $latex \boldsymbol{40.0 \;\Omega} $ resistor, a 3.00 mH inductor, a $latex \boldsymbol{5.00 \;\mu F} $ capacitor, and a voltage source with a $latex \boldsymbol{V_{\textbf{rms}}} $ of 120 V: (a) Calculate the power factor and phase angle for $latex \boldsymbol{f = 60.0 \textbf{Hz}} $. (b) What is the average power at 50.0 Hz? (c) Find the average power at the circuit’s resonant frequency.

Strategy and Solution for (a)

The power factor at 60.0 Hz is found from

We know $latex \boldsymbol{Z = 531 \;\Omega} $ from Example 1, so that

This small value indicates the voltage and current are significantly out of phase. In fact, the phase angle is

Discussion for (a)

The phase angle is close to $latex \boldsymbol{90^{\circ}} $, consistent with the fact that the capacitor dominates the circuit at this low frequency (a pure RC circuit has its voltage and current $latex \boldsymbol{90^{\circ}} $ out of phase).

Strategy and Solution for (b)

The average power at 60.0 Hz is

$latex \boldsymbol{I_{\textbf{rms}}} $ was found to be 0.226 A in Example 1. Entering the known values gives

Strategy and Solution for (c)

At the resonant frequency, we know $latex \boldsymbol{\textbf{cos} \;\phi = 1} $, and $latex \boldsymbol{I_{\textbf{rms}}} $ was found to be 6.00 A in Example 2. Thus,

$latex \boldsymbol{P_{\textbf{ave}} = (3.00 \;\textbf{A})(120 \;\textbf{V})(1) = 360 \;\textbf{W}} $ at resonance (1.30 kHz)

Discussion

Both the current and the power factor are greater at resonance, producing significantly greater power than at higher and lower frequencies.

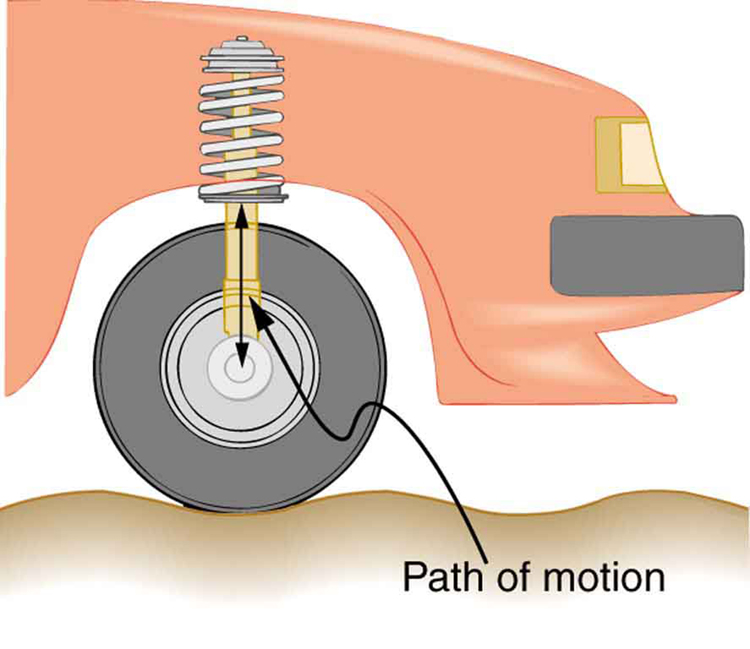

Power delivered to an RLC series AC circuit is dissipated by the resistance alone. The inductor and capacitor have energy input and output but do not dissipate it out of the circuit. Rather they transfer energy back and forth to one another, with the resistor dissipating exactly what the voltage source puts into the circuit. This assumes no significant electromagnetic radiation from the inductor and capacitor, such as radio waves. Such radiation can happen and may even be desired, as we will see in the next chapter on electromagnetic radiation, but it can also be suppressed as is the case in this chapter. The circuit is analogous to the wheel of a car driven over a corrugated road as shown in Figure 4. The regularly spaced bumps in the road are analogous to the voltage source, driving the wheel up and down. The shock absorber is analogous to the resistance damping and limiting the amplitude of the oscillation. Energy within the system goes back and forth between kinetic (analogous to maximum current, and energy stored in an inductor) and potential energy stored in the car spring (analogous to no current, and energy stored in the electric field of a capacitor). The amplitude of the wheels’ motion is a maximum if the bumps in the road are hit at the resonant frequency.

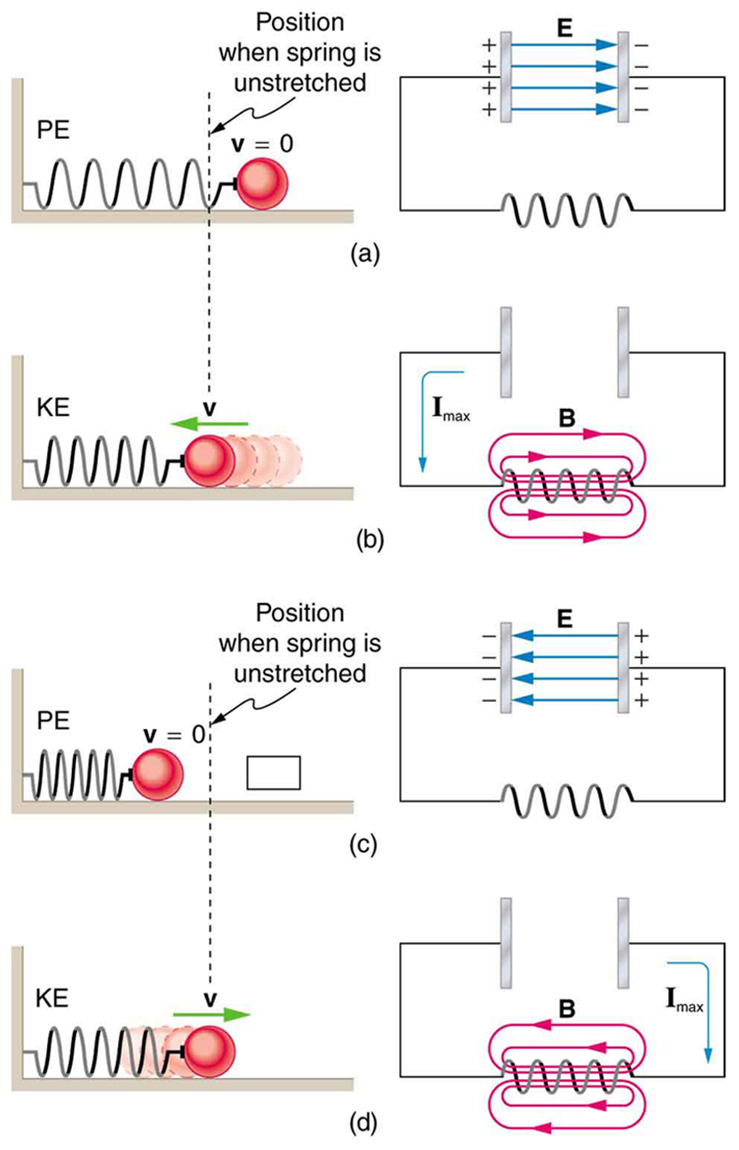

A pure LC circuit with negligible resistance oscillates at $latex \boldsymbol{f_0} $, the same resonant frequency as an RLC circuit. It can serve as a frequency standard or clock circuit—for example, in a digital wristwatch. With a very small resistance, only a very small energy input is necessary to maintain the oscillations. The circuit is analogous to a car with no shock absorbers. Once it starts oscillating, it continues at its natural frequency for some time. Figure 5 shows the analogy between an LC circuit and a mass on a spring.

PhET Explorations: Circuit Construction Kit (AC+DC), Virtual Lab

Build circuits with capacitors, inductors, resistors and AC or DC voltage sources, and inspect them using lab instruments such as voltmeters and ammeters.

Section Summary

- The AC analogy to resistance is impedance $latex \boldsymbol{Z} $, the combined effect of resistors, inductors, and capacitors, defined by the AC version of Ohm’s law:

where $latex \boldsymbol{I_0} $ is the peak current and $latex \boldsymbol{V_0} $ is the peak source voltage.

- Impedance has units of ohms and is given by $latex \boldsymbol{Z = \sqrt{R^2 + (X_L-X_C)^2}} $.

- The resonant frequency $latex \boldsymbol{f_0} $, at which $latex \boldsymbol{X_L = X_C} $, is

.

- In an AC circuit, there is a phase angle $latex \boldsymbol{\phi} $ between source voltage $latex \boldsymbol{V} $ and the current $latex \boldsymbol{I} $, which can be found from

,

- $latex \boldsymbol{\phi =0^{\circ}} $ for a purely resistive circuit or an RLC circuit at resonance.

- The average power delivered to an RLC circuit is affected by the phase angle and is given by

$latex \boldsymbol{P_{\textbf{ave}} = I_{\textbf{rms}}V_{\textbf{rms}} \;\textbf{cos} \;\phi}, $

$latex \boldsymbol{\textbf{cos} \;\phi} $ is called the power factor, which ranges from 0 to 1.

Conceptual Questions

1: Does the resonant frequency of an AC circuit depend on the peak voltage of the AC source? Explain why or why not.

2: Suppose you have a motor with a power factor significantly less than 1. Explain why it would be better to improve the power factor as a method of improving the motor’s output, rather than to increase the voltage input.

Problems & Exercises

1: An RL circuit consists of a $latex \boldsymbol{40.0 \;\Omega} $ resistor and a 3.00 mH inductor. (a) Find its impedance $latex \boldsymbol{Z} $ at 60.0 Hz and 10.0 kHz. (b) Compare these values of $latex \boldsymbol{Z} $ with those found in Example 1 in which there was also a capacitor.

2: An RC circuit consists of a $latex \boldsymbol{40.0 \;\Omega} $ resistor and a $latex \boldsymbol{5.00 \;\mu F} $ capacitor. (a) Find its impedance at 60.0 Hz and 10.0 kHz. (b) Compare these values of $latex \boldsymbol{Z} $ with those found in Example 1, in which there was also an inductor.

3: An LC circuit consists of a $latex \boldsymbol{3.00 \;\textbf{mH}} $ inductor and a $latex \boldsymbol{5.00 \;\mu F} $ capacitor. (a) Find its impedance at 60.0 Hz and 10.0 kHz. (b) Compare these values of $latex \boldsymbol{Z} $ with those found in Example 1 in which there was also a resistor.

4: What is the resonant frequency of a 0.500 mH inductor connected to a $latex \boldsymbol{40.0 \; \mu F} $ capacitor?

5: To receive AM radio, you want an RLC circuit that can be made to resonate at any frequency between 500 and 1650 kHz. This is accomplished with a fixed $latex \boldsymbol{1.00 \;\mu \textbf{H}} $ inductor connected to a variable capacitor. What range of capacitance is needed?

6: Suppose you have a supply of inductors ranging from 1.00 nH to 10.0 H, and capacitors ranging from 1.00 pF to 0.100 F. What is the range of resonant frequencies that can be achieved from combinations of a single inductor and a single capacitor?

7: What capacitance do you need to produce a resonant frequency of 1.00 GHz, when using an 8.00 nH inductor?

8: What inductance do you need to produce a resonant frequency of 60.0 Hz, when using a 2.00 μF2.00 μF capacitor?

9: The lowest frequency in the FM radio band is 88.0 MHz. (a) What inductance is needed to produce this resonant frequency if it is connected to a 2.50 pF capacitor? (b) The capacitor is variable, to allow the resonant frequency to be adjusted to as high as 108 MHz. What must the capacitance be at this frequency?

10: An RLC series circuit has a $latex \boldsymbol{2.50 \;\Omega} $ resistor, a $latex \boldsymbol{100 \;\mu \textbf{H}} $ inductor, and an $latex \boldsymbol{80.0 \;\mu \textbf{F}} $ capacitor.(a) Find the circuit’s impedance at 120 Hz. (b) Find the circuit’s impedance at 5.00 kHz. (c) If the voltage source has $latex \boldsymbol{V_{\textbf{rms}} = 5.60 \;\textbf{V}} $, what is $latex \boldsymbol{I_{\textbf{rms}}} $ at each frequency? (d) What is the resonant frequency of the circuit? (e) What is $latex \boldsymbol{I_{\textbf{rms}}} $ at resonance?

11: An RLC series circuit has a $latex \boldsymbol{1.00 \;\textbf{k} \Omega} $ resistor, a $latex \boldsymbol{150 \;\mu \textbf{H}} $ inductor, and a 25.0 nF capacitor. (a) Find the circuit’s impedance at 500 Hz. (b) Find the circuit’s impedance at 7.50 kHz. (c) If the voltage source has $latex \boldsymbol{V_{\textbf{rms}} = 408 \;\textbf{V}} $, what is $latex \boldsymbol{I_{\textbf{rms}}} $ at each frequency? (d) What is the resonant frequency of the circuit? (e) What is $latex \boldsymbol{I_{\textbf{rms}}} $ at resonance?

12: An RLC series circuit has a $latex \boldsymbol{2.50 \;\Omega} $ resistor, a $latex \boldsymbol{100 \;\mu H} $ inductor, and an $latex \boldsymbol{80.0 \;\mu \textbf{F}} $ capacitor. (a) Find the power factor at $latex \boldsymbol{f = 120 \;\textbf{Hz}} $. (b) What is the phase angle at 120 Hz? (c) What is the average power at 120 Hz? (d) Find the average power at the circuit’s resonant frequency.

13: An RLC series circuit has a $latex \boldsymbol{1.00 \;\textbf{k} \Omega} $ resistor, a $latex \boldsymbol{150 \;\mu \textbf{H}} $ inductor, and a 25.0 nF capacitor. (a) Find the power factor at $latex \boldsymbol{f = 7.50 \;\textbf{Hz}} $. (b) What is the phase angle at this frequency? (c) What is the average power at this frequency? (d) Find the average power at the circuit’s resonant frequency.

14: An RLC series circuit has a $latex \boldsymbol{200 \;\Omega} $ resistor and a 25.0 mH inductor. At 8000 Hz, the phase angle is $latex \boldsymbol{45.0^{\circ}} $. (a) What is the impedance? (b) Find the circuit’s capacitance. (c) If $latex \boldsymbol{V_{\textbf{rms}} = 408 \;\textbf{V}} $ is applied, what is the average power supplied?

15: Referring to Example 3, find the average power at 10.0 kHz.

Glossary

- impedance

- the AC analogue to resistance in a DC circuit; it is the combined effect of resistance, inductive reactance, and capacitive reactance in the form $latex \boldsymbol{Z = \sqrt{R^2 + (X_L-X_C)^2}} $

- resonant frequency

- the frequency at which the impedance in a circuit is at a minimum, and also the frequency at which the circuit would oscillate if not driven by a voltage source; calculated by $latex \boldsymbol{f_0 = \frac{1}{2 \pi \sqrt{LC}}} $

- phase angle

- denoted by $latex \boldsymbol{\phi} $, the amount by which the voltage and current are out of phase with each other in a circuit

- power factor

- the amount by which the power delivered in the circuit is less than the theoretical maximum of the circuit due to voltage and current being out of phase; calculated by $latex \boldsymbol{\textbf{cos} \;\phi} $

Solutions

Problems & Exercises

1: (a) $latex \boldsymbol{40.02 \;\Omega} $ at 60.0 Hz, $latex \boldsymbol{193 \;\Omega} $ at 10.0 kHz

(b) At 60 Hz, with a capacitor, $latex \boldsymbol{\textbf{Z} = 531 \;\Omega} $, over 13 times as high as without the capacitor. The capacitor makes a large difference at low frequencies. At 10 kHz, with a capacitor $latex \boldsymbol{\textbf{Z} = 190 \;\Omega} $, about the same as without the capacitor. The capacitor has a smaller effect at high frequencies.

3: (a) $latex \boldsymbol{529 \;\Omega} $ at 60.0 Hz, $latex \boldsymbol{185 \;\Omega} $ at 10.0 kHz

(b) These values are close to those obtained in Example 1 because at low frequency the capacitor dominates and at high frequency the inductor dominates. So in both cases the resistor makes little contribution to the total impedance.

5: 9.30 nF to 101 nF

7: 3.17 pF

9: (a) $latex \boldsymbol{1.31 \;\mu \textbf{H}} $

(b) 1.66 pF

11: (a) $latex \boldsymbol{12.8 \;\textbf{k} \Omega} $

(b) $latex \boldsymbol{1.31 \;\textbf{k} \Omega} $

(c) 31.9 mA at 500 Hz, 312 mA at 7.50 kHz

(d) 82.2 kHz

(e) 0.408 A

13: (a) 0.159

(b) $latex \boldsymbol{80.9^{\circ}} $

(c) 26.4 W

(d) 166 W

15: 16.0 W