7 Administrative and Environmental Law

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Understand the purpose served by federal administrative agencies.

- Know the difference between executive branch agencies and independent agencies.

- Understand the political control of agencies by the president and Congress.

- Describe how agencies make rules and conduct hearings.

- Describe how courts can be used to challenge administrative rulings.

From the 1930s on, administrative agencies, law, and procedures have virtually remade our government and much of private life. Every day, business must deal with rules and decisions of state and federal administrative agencies. Informally, such rules are often called regulations, and they differ (only in their source) from laws passed by Congress and signed into law by the president. The rules created by agencies are voluminous: thousands of new regulations pour forth each year. The overarching question of whether there is too much regulation—or the wrong kind of regulation—of our economic activities is an important one but well beyond the scope of this chapter, in which we offer an overview of the purpose of administrative agencies, their structure, and their impact on business.

7.1 Administrative Agencies: Their Structure and Powers

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to do the following:

- Explain the reasons why we have federal administrative agencies.

- Explain the difference between executive branch agencies and independent agencies.

- Describe the constitutional issue that questions whether administrative agencies could have authority to make enforceable rules that affect business.

7.1.1 Why Have Administrative Agencies?

The US Constitution mentions only three branches of government: legislative, executive, and judicial (Articles I, II, and III). There is no mention of agencies in the Constitution, even though federal agencies are sometimes referred to as “the fourth branch of government.” The Supreme Court has recognized the legitimacy of federal administrative agencies[1] to make rules that have the same binding effect as statutes by Congress.

Most commentators note that having agencies with rule-making power is a practical necessity:

(1) Congress does not have the expertise or continuity to develop specialized knowledge in various areas (e.g., communications, the environment, aviation). (2) Because of this, it makes sense for Congress to set forth broad statutory guidance to an agency and delegate authority to the agency to propose rules that further the statutory purposes. (3) As long as Congress makes this delegating guidance sufficiently clear, it is not delegating improperly. If Congress’s guidelines are too vague or undefined, it is (in essence) giving away its constitutional power to some other group, and this it cannot do.

7.1.2 Why Regulate the Economy at All?

The market often does not work properly, as economists usually note. Monopolies, for example, happen in the natural course of human events but are not always desirable. To fix this, well- conceived and objectively enforced competition law (what is called antitrust law in the United States) can be helpful. Negative externalities must be “fixed,” as well. For example, as we see in tort law, people and business organizations often do things that impose costs (damages) on others, and the legal system will try—through the award of compensatory damages—to make fair adjustments. In terms of the ideal conditions for a free market, think of tort law as the legal system’s attempt to compensate for negative externalities: those costs imposed on people who have not voluntarily consented to bear those costs.

In short, some forms of legislation and regulation are needed to counter a tendency toward consolidation of economic power and discriminatory attitudes toward certain individuals and groups and to insist that people and companies clean up their own messes and not hide information that would empower voluntary choices in the free market.

But there are additional reasons to regulate. For example, in economic systems, it is likely for natural monopolies to occur. These are where one firm can most efficiently supply all of the good or service. Having duplicate (or triplicate) systems for supplying electricity, for example, would be inefficient, so most states have a public utilities commission to determine both price and quality of service. This is direct regulation.

Other market imperfections can yield a demand for regulation. For example, there is a need to regulate frequencies for public broad- cast on radio, television, and other wireless transmissions (for police, fire, national defense, etc.). Many economists would also list an adequate supply of public goods as some- thing that must be created by government. On its own, for example, the market would have difficulty completely providing public goods such as education, a highway system, a military for defense.

Other market imperfections can yield a demand for regulation. For example, there is a need to regulate frequencies for public broad- cast on radio, television, and other wireless transmissions (for police, fire, national defense, etc.). Many economists would also list an adequate supply of public goods as some- thing that must be created by government. On its own, for example, the market would have difficulty completely providing public goods such as education, a highway system, a military for defense.

At the same time, government regulation can go beyond correcting externalities and market imperfections. Often government agencies are subject to “capture” by the very industry they were created to regulate, and so regulations are issued that preserve monopoly power, limit consumer choice, favor certain businesses, and so on.

7.1.3 History of Federal Agencies

Through the commerce clause in the US Constitution, Congress has the power to regulate trade between the states and with foreign nations. The earliest federal agency therefore dealt with trucking and railroads, to literally set the rules of the road for interstate commerce. The first federal agency, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), was created in 1887. Congress delegated to the ICC the power to enforce federal laws against railroad rate discrimination and other unfair pricing practices. By the early part of this century, the ICC gained the power to fix rates. From the 1970s through 1995, however, Congress passed deregulatory measures, and the ICC was formally abolished in 1995, with its powers transferred to the Surface Transportation Board.

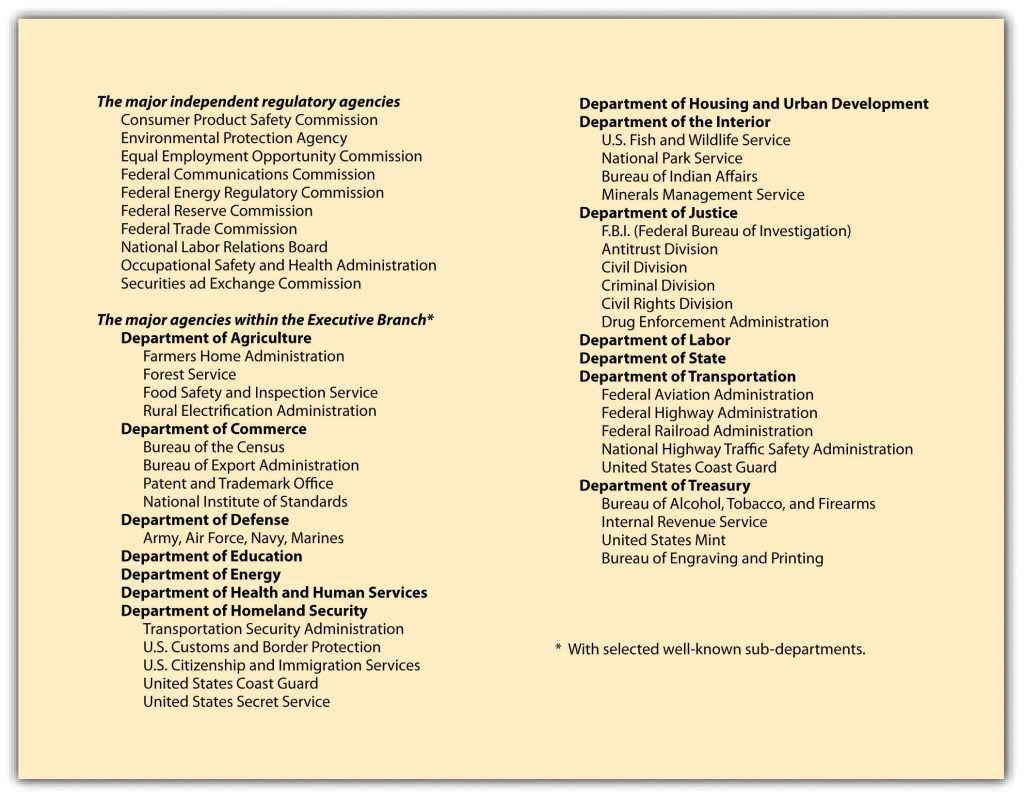

Beginning with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in 1914, Congress has created numerous other agencies, many of them familiar actors in American government. Today more than eighty-five federal agencies have jurisdiction to regulate some form of private activity. Most were created since 1930 with the Supreme Court’s expansive interpretation of the Commerce Clause (more ability to legally regulate led to more regulatory agencies), and more than a third since 1960. A similar growth has occurred at the state level. Most states now have dozens of regulatory agencies, many of them overlapping in function with the federal bodies.

Optional Viewing: Iowa Leaders in the Law

Secretary of Agriculture Thomas Vilsack is an Iowa lawyer, former Governor of the State of Iowa, and has served in the Cabinets of two different Presidents. In this interview, Professor Dayton discusses Sec. Vilsack’s road from being an orphan to heading up one of the most important administrative agencies in the federal government.

7.1.4 Classification of Agencies

Independent agencies are different from federal executive departments and other executive agencies by their structural and functional characteristics. Most executive departments have a single director, administrator, or secretary appointed by the president of the United States. Independent agencies almost always have a commission or board consisting of five to seven members who share power over the agency. The president appoints the commissioners or board subject to Senate confirmation, but they often serve with staggered terms and often for longer terms than a usual four-year presidential term. They cannot be removed except for “good cause.” This means that most presidents will not get to appoint all the commissioners of a given independent agency. Most independent agencies have a statutory requirement of bipartisan membership on the commission, so the president cannot simply fill vacancies with members of his own political party.

In addition to the ICC and the FTC, the major independent agencies are the Federal Communications Commission (1934), Securities and Exchange Commission (1934), National Labor Relations Board (1935), and Environmental Protection Agency (1970).

By contrast, members of executive branch agencies serve at the pleasure of the president and are therefore far more amenable to political control. One consequence of this distinction is that the rules that independent agencies promulgate may not be reviewed by the president or his staff—only Congress may directly overrule them—whereas the White House or officials in the various cabinet departments may oversee the work of the agencies contained within them (unless specifically denied the power by Congress).

7.1.5 Powers of Agencies

Agencies have a variety of powers. Many of the original statutes that created them, like the Federal Communications Act, gave them licensing power. No party can enter into the productive activity covered by the act without prior license from the agency—for example, no utility can start up a nuclear power plant unless first approved by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. In recent years, the move toward deregulation of the economy has led to diminution of some licensing power. Many agencies also have the authority to set the rates charged by companies subject to the agency’s jurisdiction. Finally, the agencies can regulate business practices. The FTC has general jurisdiction over all business in interstate commerce to monitor and root out “unfair acts” and “deceptive practices.” The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) oversees the issuance of corporate securities and other investments and monitors the practices of the stock exchanges.

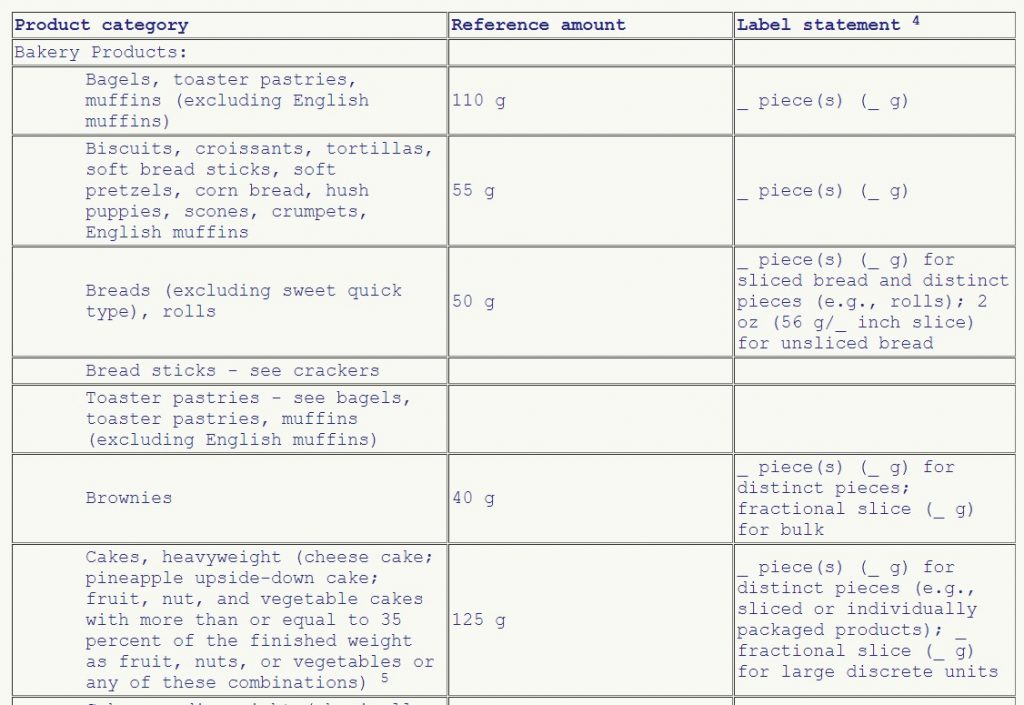

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) oversees regulation of large areas of the economy, from food labeling to prescription drugs to medical devices. For example, FDA establishes regulations for required “serving sizes” on food products. An extensive table establishes these amounts for an incredibly specific variety of foods.

Unlike courts, administrative agencies are charged with the responsibility of carrying out a specific assignment or reaching a goal or set of goals. They are not to remain neutral on the various issues of the day; they must act. They have been given legislative powers because in a society growing ever more complex, Congress does not know how to legislate with the kind of detail that is necessary, nor would it have the time to approach all the sectors of society even if it tried. Precisely because they are to do what general legislative bodies cannot do, agencies are specialized bodies. Through years of experience in dealing with similar problems they accumulate a body of knowledge that they can apply to accomplish their statutory duties.

All administrative agencies have two different sorts of personnel. The heads, whether a single administrator or a collegial body of commissioners, are political appointees and serve for relatively limited terms. Below them is a more or less permanent staff—the bureaucracy. Much policy making occurs at the staff level, because these employees are in essential control of gathering facts and presenting data and argument to the commissioners, who wield the ultimate power of the agencies.

7.1.6 The Constitution and Agencies

Congress can establish an agency through legislation. When Congress gives powers to an agency, the legislation is known as an enabling act.[2] The concept that Congress can delegate power to an agency is known as the delegation doctrine.[3] Usually, the agency will have all three kinds of power: executive, legislative, and judicial. (That is, the agency can set the rules that business must comply with, can investigate and prosecute those businesses, and can hold administrative hearings for violations of those rules. They are, in effect, rule maker, prosecutor, and judge.) Because agencies have all three types of governmental powers, important constitutional questions were asked when Congress first created them. The most important question was whether Congress was giving away its legislative power. Was the separation of powers violated if agencies had power to make rules that were equivalent to legislative statutes?

In 1935, in Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, the Supreme Court overturned the National Industrial Recovery Act on the ground that the congressional delegation of power was too broad.[4] Under the law, industry trade groups were granted the authority to devise a code of fair competition for the entire industry, and these codes became law if approved by the president. No administrative body was created to scrutinize the arguments for a particular code, to develop evidence, or to test one version of a code against another. Thus it was unconstitutional for the Congress to transfer all of its legislative powers to an agency. In later decisions, it was made clear that Congress could delegate some of its legislative powers, but only if the delegation of authority was not overly broad.

Still, some congressional enabling acts are very broad, such as the enabling legislation for the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), which is given the authority to make rules to provide for safe and healthful working conditions in US workplaces. Such a broad initiative power gives OSHA considerable discretion. But, as noted in “Controlling Administrative Agencies”, there are both executive and judicial controls over administrative agency activities, as well as ongoing control by Congress through funding and the continuing oversight of agencies, both in hearings and through subsequent statutory amendments.

Key Takeaway

Congress creates administrative agencies through enabling acts. In these acts, Congress must delegate authority by giving the agency some direction as to what it wants the agency to do. Agencies are usually given broad powers to investigate, set standards (promulgating regulations), and enforce those standards. Most agencies are executive branch agencies, but some are independent.

7.2 Controlling Administrative Agencies

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to do the following:

- Understand how the president controls administrative agencies.

- Understand how Congress controls administrative agencies.

- Understand how the courts can control administrative agencies.

During the course of the past seventy years, a substantial debate has been conducted, often in shrill terms, about the legitimacy of administrative lawmaking. One criticism is that agencies are “captured” by the industry they are directed to regulate. Another is that they overregulate, stifling individual initiative and the ability to compete. During the 1960s and 1970s, a massive outpouring of federal law created many new agencies and greatly strengthened the hands of existing ones. In the late 1970s during the Carter administration, Congress began to deregulate American society, and deregulation increased under the Reagan administration. But the accounting frauds of WorldCom, Enron, and others led to the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, and the financial meltdown of 2008 has led to reregulation of the financial sector. In the 2010s, the Trump administration set about a large scheme of government deregulation, citing concerns that regulation impaired business productivity.

Administrative agencies are the focal point of controversy because they are policy-making bodies, incorporating facets of legislative, executive, and judicial power in a hybrid form that fits uneasily at best in the framework of American government. They are necessarily at the center of tugging and hauling by the legislature, the executive branch, and the judiciary, each of which has different means of exercising political control over them. In early 1990, for example, the Bush administration approved a Food and Drug Administration regulation that limited disease-prevention claims by food packagers, reversing a position by the Reagan administration in 1987 permitting such claims.

7.2.1 Legislative Control

Congress can always pass a law repealing a regulation that an agency promulgates. Because this is a time-consuming process that runs counter to the reason for creating administrative bodies, it happens rarely. Another approach to controlling agencies is to reduce or threaten to reduce their appropriations. By retaining ultimate control of the purse strings, Congress can exercise considerable informal control over regulatory policy.

7.2.2 Executive Control

The president (or a governor, for state agencies) can exercise considerable control over agencies that are part of his cabinet departments and that are not statutorily defined as independent. Federal agencies, moreover, are subject to the fiscal scrutiny of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), subject to the direct control of the president. Agencies are not permitted to go directly to Congress for increases in budget; these requests must be submitted through the OMB, giving the president indirect leverage over the continuation of administrators’ programs and policies.

7.2.3 Judicial Review of Agency Actions

Administrative agencies are creatures of law and like everyone else must obey the law. The courts have jurisdiction to hear claims that the agencies have overstepped their legal authority or have acted in some unlawful manner.

Courts are unlikely to overturn administrative actions, often believing that the agencies are better situated to judge their own jurisdiction and are experts in rulemaking for those matters delegated to them by Congress. In a famous case referred to as Chevron,[5] the United States Supreme Court established the doctrine of “Chevron deference.” This doctrine states that courts should defer to how agencies interpret statutes. If Congress did not speak clearly to an issue, courts must defer to the agency’s “permissible” or “reasonable” interpretation of the statute. However, the Chevron doctrine was repealed in Loper Bright – please see Chapter 15 for this update.

Key Takeaway

Administrative agencies are given unusual powers: to legislate, investigate, and adjudicate. But these powers are limited by executive and legislative controls and by judicial review.

7.3 The Administrative Procedure Act

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to do the following:

- Understand why the Administrative Procedure Act was needed.

- Understand how hearings are conducted under the act.

- Understand how the act affects rulemaking by agencies.

In 1946, Congress enacted the Administrative Procedure Act (APA).[6] This fundamental statute detailed for all federal administrative agencies how they must function when they are deciding cases or issuing regulations, the two basic tasks of administration. At the state level, the Model State Administrative Procedure Act, issued in 1946 and revised in 1961, has been adopted in twenty-eight states and the District of Columbia; three states have adopted the 1981 revision. The other states have statutes that resemble the model state act to some degree.

7.3.1 Trial-Type Hearings

Deciding cases is a major task of many agencies. For example, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is empowered to charge a company with having violated the Federal Trade Commission Act. Perhaps a seller is accused of making deceptive claims in its advertising. Proceeding in a manner similar to a court, staff counsel will prepare a case against the company, which can defend itself through its lawyers. The case is tried before an administrative law judge[7] (ALJ), formerly known as an administrative hearing examiner. The change in nomenclature was made in 1972 to enhance the prestige of ALJs and more accurately reflect their duties. Although not appointed for life as federal judges are, the ALJ must be free of assignments inconsistent with the judicial function and is not subject to supervision by anyone in the agency who carries on an investigative or prosecutorial function.

The accused parties are entitled to receive notice of the issues to be raised, to present evidence, to argue, to cross-examine, and to appear with their lawyers. Ex parte (eks PAR- tay) communications—contacts between the ALJ and outsiders or one party when both par- ties are not present—are prohibited. However, the usual burden-of-proof standard followed in a civil proceeding in court does not apply: the ALJ is not bound to decide in favor of that party producing the more persuasive evidence.

The accused parties are entitled to receive notice of the issues to be raised, to present evidence, to argue, to cross-examine, and to appear with their lawyers. Ex parte (eks PAR- tay) communications—contacts between the ALJ and outsiders or one party when both par- ties are not present—are prohibited. However, the usual burden-of-proof standard followed in a civil proceeding in court does not apply: the ALJ is not bound to decide in favor of that party producing the more persuasive evidence.

The rule in most administrative proceedings is “substantial evidence,” evidence that is not flimsy or weak, but is not necessarily overwhelming evidence, either. The ALJ in most cases will write an opinion. That opinion is not the decision of the agency, which can be made only by the commissioners or agency head. In effect, the ALJ’s opinion is appealed to the commission itself.

Certain types of agency actions that have a direct impact on individuals need not be filtered through a full-scale hearing. Safety and quality inspections (grading of food, inspection of airplanes) can be made on the spot by skilled inspectors. Certain licenses can be administered through tests without a hearing (a test for a driver’s license), and some decisions can be made by election of those affected (labor union elections).

7.3.2 Rulemaking

Trial-type hearings generally impose on particular parties liabilities based on past or present facts. Because these cases will serve as precedents, they are a partial guide to future conduct by others. But they do not directly apply to nonparties, who may argue in a subsequent case that their conduct does not fit within the holding announced in the case. Agencies can affect future conduct far more directly by announcing rules that apply to all who come within the agency’s jurisdiction.

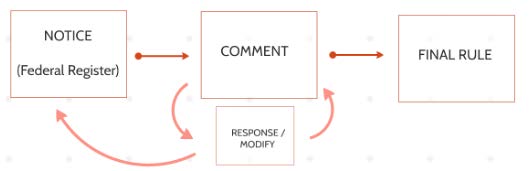

The acts creating most of the major federal agencies expressly grant them authority to engage in rulemaking. This means, in essence, authority to legislate. The outpouring of federal regulations has been immense. The APA directs agencies about to engage in rulemaking to give notice in the Federal Register[8] of their intent to do so. The Federal Register is published daily, Monday through Friday, in Washington, DC, and contains notice of various actions, including announcements of proposed rulemaking and regulations as adopted. The notice must specify the time, place, and nature of the rulemaking and offer a description of the proposed rule or the issues involved. Any interested person or organization is entitled to participate by submitting written “data, views or arguments.” Agencies are not legally required to air debate over proposed rules, though they often do so.

The procedure just described is known as “informal” rulemaking. A different procedure is required for “formal” rulemaking, defined as those instances in which the enabling legislation directs an agency to make rules “on the record after opportunity for an agency hearing.” When engaging in formal rulemaking, agencies must hold an adversary hearing.

Administrative regulations are not legally binding unless they are published. Agencies must publish in the Federal Register the text of final regulations, which ordinarily do not become effective until thirty days later. Every year the annual output of regulations is collected and reprinted in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR)[9], a multivolume paperback series containing all federal rules and regulations keyed to the fifty titles of the US Code (the compilation of all federal statutes enacted by Congress and grouped according to subject).

Key Takeaway

Agencies make rules that have the same effect as laws passed by Congress and the president. But such rules (regulations) must allow for full participation by interested parties. The Administrative Procedure Act (APA) governs both rulemaking and the agency enforcement of regulations, and it provides a process for fair hearings.

7.4 Administrative Burdens on Business Operations

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to do the following:

- Describe the paperwork burden imposed by administrative agencies.

- Explain why agencies have the power of investigation, and what limits there are to that power.

- Explain the need for the Freedom of Information Act and how it works in the US

legal system.

7.4.1 The Paperwork Burden

The administrative process is not frictionless. The interplay between government agency and private enterprise can burden business operations in a number of ways. Several of these are noted in this section.

Deciding whether and how to act are not decisions that government agencies reach out of the blue. They rely heavily on information garnered from business itself. Dozens of federal agencies require corporations to keep hundreds of types of records and to file numerous periodic reports. The Commission on Federal Paperwork, established during the Ford administration to consider ways of reducing the paperwork burden, estimated in its final report in 1977 that the total annual cost of federal paperwork amounted to $50 billion and that the 10,000 largest business enterprises spent $10 billion annually on paperwork alone. The paperwork involved in licensing a single nuclear power plant, the commission said, costs upward of $15 million.

Not surprisingly, therefore, businesses have sought ways of avoiding requests for data. Since the 1940s, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has collected economic data on corporate performance from individual companies for statistical purposes. As long as each company engages in a single line of business, data are comparable. When the era of con- glomerates began in the 1970s, with widely divergent types of businesses brought together under the roof of a single corporate parent, the data became useless for purposes of examining the competitive behavior of different industries. So the FTC ordered dozens of large companies to break out their economic information according to each line of business that they carried on. The companies resisted, but the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, where much of the litigation over federal administrative action is decided, directed the companies to comply with the commission’s order, holding that the Federal Trade Commission Act clearly permits the agency to collect information for investigatory purposes.[10]

Not surprisingly, therefore, businesses have sought ways of avoiding requests for data. Since the 1940s, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has collected economic data on corporate performance from individual companies for statistical purposes. As long as each company engages in a single line of business, data are comparable. When the era of con- glomerates began in the 1970s, with widely divergent types of businesses brought together under the roof of a single corporate parent, the data became useless for purposes of examining the competitive behavior of different industries. So the FTC ordered dozens of large companies to break out their economic information according to each line of business that they carried on. The companies resisted, but the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, where much of the litigation over federal administrative action is decided, directed the companies to comply with the commission’s order, holding that the Federal Trade Commission Act clearly permits the agency to collect information for investigatory purposes.[10]

In 1980, responding to cries that businesses, individuals, and state and local governments were being swamped by federal demands for paperwork, Congress enacted the Paperwork Reduction Act. It gives power to the federal Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to develop uniform policies for coordinating the gathering, storage, and transmission of all the millions of reports flowing in each year to the scores of federal departments and agencies requesting information. These reports include tax and Medicare forms, financial loan and job applications, questionnaires of all sorts, compliance reports, and tax and business records. The OMB was given the power also to determine whether new kinds of information are needed. In effect, any agency that wants to collect new information from outside must obtain the OMB’s approval.

7.4.2 Inspections

No one likes surprise inspections. A section of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 empowers agents of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to search work areas for safety hazards and for violations of OSHA regulations. The act does not specify whether inspectors are required to obtain search warrants, required under the Fourth Amendment in criminal cases. For many years, the government insisted that surprise inspections are not unreasonable and that the time required to obtain a warrant would defeat the surprise element. The Supreme Court finally ruled squarely on the issue in 1978. In Marshall v. Barlow’s, Inc., the court held that no less than private individuals, businesses are entitled to refuse police demands to search the premises unless a court has issued a search warrant.[11]

But where a certain type of business is closely regulated, surprise inspections are the norm, and no warrant is required. For example, businesses with liquor licenses that might sell to minors are subject to both overt and covert inspections (e.g., an undercover officer may “search” a liquor store by sending an underage patron to the store). Or a junkyard that specializes in automobiles and automobile parts may also be subject to surprise inspections, on the rationale that junkyards are highly likely to be active in the resale of stolen autos or stolen auto parts.[12]

It is also possible for inspections to take place without a search warrant and without the permission of the business. For example, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) wished to inspect parts of the Dow Chemical facility in Midland, Michigan, without the benefit of warrant. When they were refused, agents of the EPA obtained a fairly advanced aerial mapping camera and rented an airplane to fly over the Dow facility. Dow went to court for a restraining order against the EPA and a request to have the EPA turn over all photographs taken. But the Supreme Court ruled that the areas photographed were “open fields” and not subject to the protections of the Fourth Amendment.[13]

7.4.3 Access to Business Information in Government Files

In 1966, Congress enacted the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), opening up to the citizenry many of the files of the government. (The act was amended in 1974 and again in 1976 to overcome a tendency of many agencies to stall or refuse access to their files.) Under the FOIA, any person has a legally enforceable right of access to all government documents, with nine specific exceptions, such as classified military intelligence, medical files, and trade secrets and commercial or financial information if “obtained from a person and privileged or confidential.” Without the trade-secret and financial-information exemptions, business competitors could, merely by requesting it, obtain highly sensitive competitive information sitting in government files.

A federal agency is required under the FOIA to respond to a document request within ten days. But in practice, months or even years may pass before the government actually responds to an FOIA re- quest. Requesters must also pay the cost of locating and copying the records. Moreover, not all documents are available for public inspection. Along with the trade-secret and financial-information ex- emptions, the FOIA specifically exempts the following:

A federal agency is required under the FOIA to respond to a document request within ten days. But in practice, months or even years may pass before the government actually responds to an FOIA re- quest. Requesters must also pay the cost of locating and copying the records. Moreover, not all documents are available for public inspection. Along with the trade-secret and financial-information ex- emptions, the FOIA specifically exempts the following:

- Records required by executive order of the president to be kept secret in the interest of national defense or public policy;

- Records related solely to the internal personnel rules and practice of an agency;

- Records exempted from disclosure by another statute;

- Interagency memos or decisions reflecting the deliberative process;

- Personnel files and other files that if disclosed, would constitute an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy;

- Information compiled for law enforcement purposes; and

- Geological information concerning wells.

Note that the government may provide such information but is not required to provide such information; it retains discretion to provide information or not.

Regulated companies are often required to submit confidential information to the government. For these companies, submitting such information presents a danger under the FOIA of disclosure to competitors. To protect information from disclosure, the company is well advised to mark each document as privileged and confidential so that government officials reviewing it for a FOIA request will not automatically disclose it. Most agencies notify a company whose data they are about to disclose. But these practices are not legally required under the FOIA.

Key Takeaway

Government agencies, in order to do their jobs, collect a great deal of information from businesses. This can range from routine paperwork (often burdensome) to inspections, those with warrants and those without. Surprise inspections are allowed for closely regulated industries but are subject to Fourth Amendment requirements in general. Some information collected by agencies can be accessed using the Freedom of Information Act.

7.5 The Scope of Judicial Review

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to do the following:

- Describe the “exhaustion of remedies” requirement.

- Detail various strategies for obtaining judicial review of agency rules.

- Explain under what circumstances it is possible to sue the government.

Neither an administrative agency’s adjudication nor its issuance of a regulation is necessarily final. Most federal agency decisions are appealable to the federal circuit courts. To get to court, the appellant must overcome numerous complex hurdles. He or she must have standing—that is, be in some sense directly affected by the decision or regulation. The case must be ripe for review; administrative remedies such as further appeal within the agency must have been exhausted.

7.5.1 Exhaustion of Administrative Remedies

Before you can complain to court about an agency’s action, you must first try to get the agency to reconsider its action. Generally, you must have asked for a hearing at the hearing examiner level, there must have been a decision reached that was unfavorable to you, and you must have appealed the decision to the full board. The full board must rule against you, and only then will you be heard by a court. The broadest exception to this exhaustion of administrative remedies[14] requirement is if the agency had no authority to issue the rule or regulation in the first place, if exhaustion of remedies would be impractical or futile, or if great harm would happen should the rule or regulation continue to apply. Also, if the agency is not acting in good faith, the courts will hear an appeal without exhaustion.

7.5.2 Strategies for Obtaining Judicial Review

Once these obstacles are cleared, the court may look at one of a series of claims. The appellant might assert that the agency’s action was ultra vires (UL-truh VI-reez)—beyond the scope of its authority as set down in the statute. This attack is rarely successful. A somewhat more successful claim is that the agency did not abide by its own procedures or those imposed upon it by the Administrative Procedure Act.

In formal rulemaking, the appellant also might insist that the agency lacked substantial evidence for the determination that it made. If there is virtually no evidence to support the agency’s findings, the court may reverse. But findings of fact are not often overturned by the courts.

Likewise, there has long been a presumption that when an agency issues a regulation, it has the authority to do so: those opposing the regulation must bear a heavy burden in court to upset it. This is not a surprising rule, for otherwise courts, not administrators, would be the authors of regulations. Nevertheless, regulations cannot exceed the scope of the authority conferred by Congress on the agency. In an important 1981 case before the Supreme Court, the issue was whether the secretary of labor, acting through the Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA), could lawfully issue a standard limiting exposure to cotton dust in the workplace without first undertaking a cost- benefit analysis. A dozen cotton textile manufacturers and the American Textile Manufacturers Institute, representing 175 companies, asserted that the cotton dust standard was unlawful because it did not rationally relate the benefits to be derived from the standard to the costs that the standard would impose.

Likewise, there has long been a presumption that when an agency issues a regulation, it has the authority to do so: those opposing the regulation must bear a heavy burden in court to upset it. This is not a surprising rule, for otherwise courts, not administrators, would be the authors of regulations. Nevertheless, regulations cannot exceed the scope of the authority conferred by Congress on the agency. In an important 1981 case before the Supreme Court, the issue was whether the secretary of labor, acting through the Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA), could lawfully issue a standard limiting exposure to cotton dust in the workplace without first undertaking a cost- benefit analysis. A dozen cotton textile manufacturers and the American Textile Manufacturers Institute, representing 175 companies, asserted that the cotton dust standard was unlawful because it did not rationally relate the benefits to be derived from the standard to the costs that the standard would impose.

In summary, then, an individual or a company may (after exhaustion of administrative remedies) challenge agency action where such action is the following:

- Not in accordance with the agency’s scope of authority;

- Not in accordance with the US Constitution or the Administrative Procedure Act;

- Not in accordance with the substantial evidence test;

- Unwarranted by the facts; or

- Arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accord with the law.

Section 706 of the Administrative Procedure Act sets out those standards. While it is difficult to show that an agency’s action is arbitrary and capricious, there are cases that have so held. For example, after the Reagan administration set aside a Carter administration rule from the National Highway Traffic and Safety Administration on passive restraints in automobiles, State Farm and other insurance companies challenged the reversal as arbitrary and capricious. Examining the record, the Supreme Court found that the agency had failed to state enough reasons for its reversal and required the agency to review the record and the rule and provide adequate reasons for its reversal. State Farm and other insurance companies thus gained a legal benefit by keeping an agency rule that placed costs on automakers for increased passenger safety and potentially reducing the number of injury claims from those it had insured.[15]

7.5.3 Suing the Government

In the modern administrative state, the range of government activity is immense, and administrative agencies frequently get in the way of business enterprise. Often, bureaucratic involvement is wholly legitimate, compelled by law; sometimes, however, agencies or government officials may overstep their bounds, in a fit of zeal or spite. What recourse does the private individual or company have?

Mainly for historical reasons, it has always been more difficult to sue the government than to sue private individuals or corporations. For one thing, the government has long had recourse to the doctrine of sovereign im- munity as a shield against lawsuits. Yet in 1976, Congress amended the Administrative Procedure Act to waive any federal claim to sovereign immunity in cases of injunctive or other nonmonetary relief. Earlier, in 1946, in the Federal Tort Claims Act, Congress had waived sovereign immunity of the federal government for most tort claims for money damages, although the act contains several exceptions for specific agencies (e.g., one cannot sue for injuries resulting from fiscal operations of the Treasury Department or for injuries stemming from activities of the military in wartime). The act also contains a major exception for claims “based upon [an official’s] exercise or performance or the failure to exercise or perform a discretionary function or duty.” This exception prevents suits against parole boards for paroling dangerous criminals who then kill or maim in the course of another crime and suits against officials whose decision to ship explosive materials by public carrier leads to mass deaths and injuries following an explosion en route.[16]

In recent years, the Supreme Court has been stripping away the traditional immunity enjoyed by many government officials against personal suits. Some government employees—judges, prosecutors, legislators, and the president, for example—have absolute immunity against suit for official actions. But many public administrators and government employees have at best a qualified immunity. Under a provision of the Civil Rights Act of 1871 (so-called Section 1983 actions), state officials can be sued in federal court for money damages whenever “under color of any state law” they deprive anyone of his rights under the Constitution or federal law. In Bivens v. Six Unknown Federal Narcotics Agents, the Supreme Court held that federal agents may be sued for violating the plaintiff’s Fourth Amendment rights against an unlawful search of his home.[17] Subsequent cases have followed this logic to permit suits for violations of other constitutional provisions. This area of the law is in a state of flux, and it is likely to continue to evolve.

Sometimes damage is done to an individual or business because the government has given out erroneous information. For example, suppose that Charles, a bewildered, disabled navy employee, is receiving a federal disability annuity. Under the regulations, he would lose his pension if he took a job that paid him in each of two succeeding years more than 80 percent of what he earned in his old navy job. A few years later, Congress changed the law, making him ineligible if he earned more than 80 percent in anyone year. For many years, Charles earned considerably less than the ceiling amount. But then one year he got the opportunity to make some extra money. Not wishing to lose his pension, he called an employee relations specialist in the US Navy and asked how much he could earn and still keep his pension. The specialist gave him erroneous information over the telephone and then sent him an out-of-date form that said Charles could safely take on the extra work. Unfortunately, as it turned out, Charles did exceed the salary limit, and so the government cut off his pension during the time he earned too much. Charles sues to recover his lost pension. He argues that he relied to his detriment on false information supplied by the navy and that in fairness the government should be estopped from denying his claim.

Unfortunately for Charles, he will lose his case. In Office of Personnel Management v. Richmond, the Supreme Court reasoned that it would be unconstitutional to permit recovery.[18] The appropriations clause of Article I says that federal money can be paid out only through an appropriation made by law. The law prevented this particular payment to be made. If the court were to make an exception, it would permit executive officials in effect to make binding payments, even though unauthorized, simply by misrepresenting the facts. The harsh reality, therefore, is that mistakes of the government are generally held against the individual, not the government, unless the law specifically provides for recompense (as, for example, in the Federal Tort Claims Act just discussed).

ENVIRONMENTAL LAW

Learning Objectives

- Describe the major federal laws that govern business activities that may adversely affect air quality and water quality.

- Describe the major federal laws that govern waste disposal and chemical hazards including pesticides.

In one sense, environmental law is very old. Medieval England had smoke control laws that established the seasons when soft coal could be burned. Nuisance laws give private individuals a limited control over polluting activities of adjacent landowners. But a comprehensive set of US laws directed toward general protection of the environment is largely a product of the past quarter-century, with most of the legislative activity stemming from the late 1960s and later, when people began to perceive that the environment was systematically deteriorating from assaults by rapid population growth and greatly increased automobile driving, vast proliferation of factories that generate waste products, and a sharp rise in the production of toxic materials. Two of the most significant developments in environmental law came in 1970, when the National Environmental Policy Act took effect and the Environmental Protection Agency became the first of a number of new federal administrative agencies to be established during the decade.

NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY ACT

Signed into law by President Nixon on January 1, 1970, the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) declared that it shall be the policy of the federal government, in cooperation with state and local governments, “to create and maintain conditions under which man and nature can exist in productive harmony, and fulfill the social, economic, and other requirements of present and future generations of Americans.. . . The Congress recognizes that each person should enjoy a healthful environment and that each person has a responsibility to contribute to the preservation and enhancement of the environment.”

The most significant aspect of NEPA is its requirement that federal agencies prepare an environmental impact statement332 in every recommendation or report on proposals for legislation and whenever undertaking a major federal action that significantly affects environmental quality. The statement must (1) detail the environmental impact of the proposed action, (2) list any unavoidable adverse impacts should the action be taken, (3) consider alternatives to the pro- posed action, (4) compare short-term and long-term consequences, and (5) describe irreversible commitments of resources. Unless the impact statement is prepared, the project can be enjoined from proceeding. Note that NEPA does not apply to purely private activities but only to those proposed to be carried out in some manner by federal agencies.

ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has been in the forefront of the news since its creation in 1970. Charged with monitoring environmental practices of industry, assisting the government and private business to halt environmental deterioration, promulgating regulations consistent with federal environmental policy, and policing industry for violations of the various federal environmental statutes and regulations, the EPA has had a pervasive influence on American business. Business Week noted the following in 1977: “Cars rolling off Detroit’s assembly line now have antipollution devices as standard equipment. The dense black smokestack emissions that used to symbolize industrial prosperity are rare, and illegal, sights. Plants that once blithely ran discharge water out of a pipe and into a river must apply for permits that are almost impossible to get unless the plants install expensive water treatment equipment. All told, the EPA has made a sizable dent in man-made environmental filth.”[15]

The EPA is especially active in regulating water and air pollution and in overseeing the disposition of toxic wastes and chemicals. Clean Water Act Legislation governing the nation’s waterways goes back a long time. The first federal water pollution statute was the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899. Congress enacted new laws in 1948, 1956, 1965, 1966, and 1970. But the centerpiece of water pollution enforcement is the Clean Water Act of 1972 (technically, the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972), as amended in 1977 and by the Water Quality Act of 1987. The Clean Water Act is designed to restore and maintain the “chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation’s waters.”33 United States Code, Section 1251. It operates on the states, requiring them to designate the uses of every significant body of water within their borders (e.g., for drinking water, recreation, commercial fishing) and to set water quality standards to reduce pollution to levels appropriate for each use.

CLEAN WATER ACT

Congress only has power to regulate interstate commerce, and so the Clean Water Act is applicable only to “navigable waters” of the United States. This has led to disputes over whether the act can apply, say, to an abandoned gravel pit that has no visible connection to navigable waterways, even if the gravel pit provides habitat for migratory birds. In Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County v. Army Corps of Engineers, the US Supreme Court said no.

Congress only has power to regulate interstate commerce, and so the Clean Water Act is applicable only to “navigable waters” of the United States. This has led to disputes over whether the act can apply, say, to an abandoned gravel pit that has no visible connection to navigable waterways, even if the gravel pit provides habitat for migratory birds. In Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County v. Army Corps of Engineers, the US Supreme Court said no.

The Clean Water Act also governs private industry and imposes stringent standards on the discharge of pollutants into waterways and publicly owned sewage systems. The act created an effluent permit system known as the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System. To discharge any pollutants into navigable waters from a “point source” like a pipe, ditch, ship, or container, a company must obtain a certification that it meets specified standards, which are continually being tightened. For example, until 1983, industry had to use the “best practicable technology” currently available, but after July 1, 1984, it had to use the “best available technology” economically achievable. Companies must limit certain kinds of “conventional pollutants” (such as suspended solids and acidity) by “best conventional control technology.”

Sackett v. EPA – What Are The “Waters of the US?”

Sackett I (566 U.S. 120 (2012)) and II (598 U.S. __ (2023)) were cases in which the definition of navigable waters, or “Waters of the US” (WOTUS) were at issue. This is important because, as noted above, only navigable waters are within the EPA’s jurisdiction under the Clean Water Act (CWA).

The Sacketts own a lot near Priest Lake, Idaho, and wish to fill that lot with dirt and rock to build a home there. However, the EPA believed the lot was within a wetland protected by the CWA, and thus unsuitable for filling and building. The EPA issued a compliance order against the Sacketts preventing them from filling and building.

It can be difficult to tell whether an area is a navigable water under the CWA definition. Some are obvious- large rivers such as the Mississippi, for example. But, some waterways may not have much, or any, water at different times of the year. Wetlands in particular may fluctuate, at times drying up and at times connecting to obviously navigable waters. Previously, the EPA had defined WOTUS broadly – “all waters that could affect interstate or foreign commerce.”

The Sacketts believed that the EPA had overstepped in two ways: by issuing a compliance order which they could not challenge in court, and by defining the wetlands on their lot as WOTUS subject to CWA jurisdiction.

In Sackett I, the Supreme Court ruled that the Sacketts had a right to challenge the EPA’s compliance order in court. In the ensuing 11 years, the Sacketts placed some sand and gravel on the disputed parcel, and also pursued their legal challenge in federal court. During that litigation, the EPA lifted their compliance order. However, the challenge as to whether the EPA has CWA jurisdiction over wetlands proceeded to the Supreme Court.

In Sackett II, the Court again ruled in favor of the Sacketts. The Court held that waters were defined under the CWA as “only those relatively permanent, standing, or continuously flowing bodies of water” – not, e.g,, wetlands that dry up at times. They further held that for a wetland (or any other waterway) to be considered WOTUS, they must have a “continuous surface connection” to navigable waters. Thus, an isolated pond or wetland (such as the one on the Sackett’s property) would not qualify as a WOTUS.

The Court’s decision may have far-reaching consequences for landowners and environmentalists alike. It is not clear from the ruling how often a continuous surface connection must be disrupted to disqualify a water as a WOTUS. With increasing droughts across the US, even major rivers like the Colorado are running dry. The Sierra Club warned, “A negative decision from the Supreme Court could open millions of acres of wetlands and millions of miles of streams – all currently protected by the Clean Water Act – to pollution and destruction.”

Conversely, the American Farm Bureau Federation welcomed the possibility of a change in the definition of WOTUS: “AFBF is pleased that the Supreme Court has agreed to take up the important issue of what constitutes ‘Waters of the U.S.’ under the Clean Water Act. Farmers and ranchers share the goal of protecting the resources they’re entrusted with, but they shouldn’t need a team of lawyers to farm their land. We hope this case will bring more clarity to water regulations.”

Special thanks to Honors student Michael W. Murnin for his research and writing on this case.

CLEAN AIR ACT

The centerpiece of the legislative effort to clean the atmosphere is the Clean Air Act of 1970 (amended in 1975, 1977, and 1990). Under this act, the EPA has set two levels of National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS). The primary standards limit the ambient (i.e., circulating) pollution that affects human health; secondary standards limit pollution that affects animals, plants, and property. The heart of the Clean Air Act is the requirement that subject to EPA approval, the states implement the standards that the EPA establishes. The setting of these pollutant standards was coupled with directing the states to develop state implementation plans (SIPs), applicable to appropriate industrial sources in the state, in order to achieve these standards. The act was amended in 1977 and 1990 primarily to set new goals (dates) for achieving attainment of NAAQS since many areas of the country had failed to meet the deadlines.

Beyond the NAAQS, the EPA has established several specific standards to control different types of air pollution. One major type is pollution that mobile sources, mainly automobiles, emit. The EPA requires new cars to be equipped with catalytic converters and to use unleaded gasoline to eliminate the most noxious fumes and to keep them from escaping into the atmosphere. To minimize pollution from stationary sources, the EPA also imposes uniform standards on new industrial plants and those that have been substantially modernized. And to safeguard against emissions from older plants, states must promulgate and enforce SIPs.

The Clean Air Act is even more solicitous of air quality in certain parts of the nation, such as designated wilderness areas and national parks. For these areas, the EPA has set standards to prevent significant deterioration in order to keep the air as pristine and clear as it was centuries ago.

TOXIC WASTE

The EPA also worries about chemicals so toxic that the tiniest quantities could prove fatal or extremely hazardous to health. To control emission of substances like asbestos, beryllium, mercury, vinyl chloride, benzene, and arsenic, the EPA has established or proposed various National Emissions Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants. Concern over acid rain and other types of air pollution prompted Congress to add almost eight hundred pages of amendments to the Clean Air Act in 1990. (The original act was fifty pages long.) As a result of these amendments, the act was modernized in a manner that parallels other environmental laws. For instance, the amendments established a permit system that is modeled after the Clean Water Act. And the amendments provide for felony convictions for willful violations, similar to penalties incorporated into other statutes.

The amendments include certain defenses for industry. Most important, companies are protected from allegations that they are violating the law by showing that they were acting in accordance with a permit. In addition to this “permit shield,” the law also contains protection for workers who unintentionally violate the law while following their employers’ instructions.

Though pollution of the air by highly toxic substances like benzene or vinyl chloride may seem a problem removed from that of the ordinary person, we are all in fact polluters. Every year, the United States generates approximately 230 million tons of “trash”—about 4.6 pounds per person per day. Less than one-quarter of it is recycled; the rest is incinerated or buried in landfills. But many of the country’s landfills have been closed, either because they were full or because they were contaminating groundwater. Once groundwater is contaminated, it is extremely expensive and difficult to clean it up. In the 1965 Solid Waste Disposal Act and the 1970 Resource Recovery Act, Congress sought to regulate the discharge of garbage by encouraging waste management and recycling. Federal grants were available for research and training, but the major regulatory effort was expected to come from the states and municipalities.

But shocking news prompted Congress to get tough in 1976. The plight of homeowners near Love Canal in upstate New York became a major national story as the discovery of massive underground leaks of toxic chemicals buried during the previous quarter century led to evacuation of hundreds of homes. Next came the revelation that Kepone, an exceedingly toxic pesticide, had been dumped into the James River in Virginia, causing a major human health hazard and severe damage to fisheries in the James and downstream in the Chesapeake Bay. The rarely discussed industrial dumping of hazardous wastes now became an open controversy, and Congress responded in 1976 with the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) and the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) and in 1980 with the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA).

The RCRA expresses a “cradle-to-grave” philosophy: hazardous wastes must be regulated at every stage. The act gives the EPA power to govern their creation, storage, transport, treatment, and disposal. Any person or company that generates hazardous waste must obtain a permit (known as a “manifest”) either to store it on its own site or ship it to an EPA-approved treatment, storage, or disposal facility. No longer can hazardous substances simply be dumped at a convenient landfill. Owners and operators of such sites must show that they can pay for damage growing out of their operations, and even after the sites are closed to further dumping, they must set aside funds to monitor and maintain the sites safely.

This philosophy can be severe. In 1986, the Supreme Court ruled that bankruptcy is not a sufficient reason for a company to abandon toxic waste dumps if state regulations reasonably require protection in the interest of public health or safety. The practical effect of the ruling is that trustees of the bankrupt company must first devote assets to cleaning up a dump site, and only from remaining assets may they satisfy creditors. Another severity is RCRA’s imposition of criminal liability, including fines of up to $25,000 a day and one-year prison sentences, which can be extended beyond owners to individual employees.

The CERCLA, also known as the Superfund, gives the EPA emergency powers to respond to public health or environmental dangers from faulty hazardous waste disposal, currently estimated to occur at more than seventeen thousand sites around the country. The EPA can direct immediate removal of wastes presenting imminent danger (e.g., from train wrecks, oil spills, leaking barrels, and fires). Injuries can be sudden and devastating; in 1979, for example, when a freight train derailed in Florida, ninety thousand pounds of chlorine gas escaped from a punctured tank car, leaving 8 motorists dead and 183 others injured and forcing 3,500 residents within a 7-mile radius to be evacuated. The EPA may also carry out “planned removals” when the danger is substantial, even if immediate removal is not necessary.

The EPA prods owners who can be located to voluntarily clean up sites they have abandoned. But if the owners refuse, the EPA and the states will undertake the task, drawing on a federal trust fund financed mainly by taxes on the manufacture or import of certain chemicals and petroleum (the balance of the fund comes from general revenues). States must finance 10 percent of the cost of cleaning up private sites and 50 percent of the cost of cleaning up public facilities. The EPA and the states can then assess unwilling owners’ punitive damages up to triple the cleanup costs.

Cleanup requirements are especially controversial when applied to landowners who innocently purchased contaminated property. To deal with this problem, Congress enacted the Superfund Amendment and Reauthorization Act in 1986, which protects innocent landowners who—at the time of purchase—made an “appropriate inquiry” into the prior uses of the property. The act also requires companies to publicly disclose information about hazardous chemicals they use. We now turn to other laws regulating chemical hazards.

CHEMICAL HAZARDS

Toxic Substances Control Act

Chemical substances that decades ago promised to improve the quality of life have lately shown their negative side—they have serious adverse side effects. For example, asbestos, in use for half a century, causes cancer and asbestosis, a debilitating lung disease, in workers who breathed in fibers decades ago. The result has been crippling disease and death and more than thirty thousand asbestos-related lawsuits filed nationwide. Other substances, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and dioxin, have caused similar tragedy. Together, the devastating effects of chemicals led to enactment of the TSCA, designed to control the manufacture, processing, commercial distribution, use, and disposal of chemicals that pose unreasonable health or environmental risks. (The TSCA does not apply to pesticides, tobacco, nuclear materials, firearms and ammunition, food, food additives, drugs, and cosmetics—all are regulated by other federal laws.)

The TSCA gives the EPA authority to screen for health and environmental risks by requiring companies to notify the EPA ninety days before manufacturing or importing new chemicals. The EPA may demand that the companies test the substances before marketing them and may regulate them in a number of ways, such as requiring the manufacturer to label its products, to keep records on its manufacturing and disposal processes, and to document all significant adverse reactions in people exposed to the chemicals. The EPA also has authority to ban certain especially hazardous substances, and it has banned the further production of PCBs and many uses of asbestos.

Both industry groups and consumer groups have attacked the TSCA. Industry groups criticize the act because the enforcement mechanism requires mountainous paperwork and leads to widespread delay. Consumer groups complain because the EPA has been slow to act against numerous chemical substances. The debate continues.

- “The Tricks of the Trade-off,” Business Week, April 4, 1977, 72. ↵

Key Takeaways

Laws limiting the use of one’s property have been around for many years; common-law restraints (e.g., the law of nuisance) exist as causes of action against those who would use their property to adversely affect the life or health of others or the value of their neighbors’ property. Since the 1960s, extensive federal laws governing the environment have been enacted. These include laws governing air, water, and chemicals. Some laws include criminal penalties for noncompliance.

- Governmental units, either state or federal, that have specialized expertise and authority over some area of the economy. ↵

- The legislative act that establishes an agency’s authority in a particular area of the economy. ↵

- As a matter of constitutional law, the delegation doctrine declares that an agency can only exercise that power delegated to it by a constitutional authority. ↵

- Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, 295 US 495 (1935). ↵

- Chevron, USA v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 467 US 837 (1984) ↵

- The federal act that governs all agency procedures in both hearings and rulemaking. ↵

- The primary hearing officer in an administrative agency, who provides the initial ruling of the agency (often called an order) in any contested proceeding. ↵

- The Federal Register is where all proposed administrative regulations are first published, usually inviting comment from interested parties. ↵

- A compilation of all final agency rules. The CFR has the same legal effect as a bill passed by Congress and signed into law by the president. ↵

- In re FTC Line of Business Report Litigation, 595 F.2d 685 (D.C. Cir. 1978). ↵

- Marshall v. Barlow’s, Inc., 436 US 307 (1978). ↵

- New York v. Burger, 482 US 691 (1987). ↵

- Dow Chemical Co. v. United States Environmental Protection Agency, 476 US 227 (1986). ↵

- A requirement that anyone wishing to appeal an agency action must wait until the agency has taken final action. ↵

- Motor Vehicle Manufacturers’ Assn. v. State Farm Mutual Ins., 463 US 29 (1983). ↵

- Dalehite v. United States, 346 US 15 (1953). ↵

- Bivens v. Six Unknown Federal Narcotics Agents, 403 US 388 (1971). ↵

- Office of Personnel Management v. Richmond, 110 S. Ct. 2465 (1990). ↵