13 Agency and Employment Law

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Explain why agency is important, what an agent is, and the types of agents.

- Understand what an independent contractor is.

- Summarize the duties owed by principals and agents.

- Explain the liability of principals and agents.

- Understand how common-law employment at will is modified by common-law doctrine, federal statutes, and state statutes.

- Explain various kinds of prohibited discrimination under Title VII and examples of each kind.

Employment law is made up of a broad body of law that governs employment relationships between a business and its employees. It consists of numerous federal and state statutes, administrative regulations, and judicial decisions. Additionally, employment law draws from other areas of law such as contracting, agency, and torts. This chapter provides an overview of some of the key concepts in this area of law.

13.1 Types of Employment Relationships

Employment law governs the relationship between an employer and its employee. There are three key types of employment relationships covered in this chapter: employment for a contracted period of time, employment at will, and independent contractors. In the United States, the majority of employment relationships are at will or through independent contractors. As you will learn, the type of employment relationship impacts the responsibilities and liabilities of both the employer and employee.

13.1.1 Employment for a Contracted Period of Time

Historically, employment by contract was the most common form of employment relationship. Under this model, employees entered into a contract to work for a company for a fixed period of time. Employees could not be fired during that time frame unless the company had a good reason for doing so. For example, a Starbucks barista could sign a contract to work for the company for a two year term. Starbucks would then be obligated to employ that barista for the full two years unless it had some “just cause” for firing him.

One benefit of the employment by contract model is that employees could not be fired without just cause. Although there is no universal meaning of the term, it generally protects individuals from being fired unless they engage in some misconduct or negligent job performance. However, individuals employed by contract cannot be fired for things like a change in market conditions, employer profitability, or reduced staffing needs. This provides more stability and predictability to employees.

Carroll Daugherty, a well-known arbitrator, created the following seven-factor test for determining whether a firm had just cause to fire an employee:

- Did the Company give to the employee forewarning or foreknowledge of the possible or probable disciplinary consequences of the employee’s conduct?

- Was the company’s rule or managerial order reasonably related to the orderly, efficient, and safe operation of the Company’s business?

- Did the company, before administering discipline to an employee make an effort to discover whether the employee did in fact violate or disobey a rule or order of management?

- Was the Company’s investigation conducted fairly and objectively?

- At the investigation did the “judge” obtain substantial evidence or proof that the employee was guilty as charged?

- Has the company applied its rules, orders, and penalties evenhandedly and without discrimination to all employees?

- Was the degree of discipline administered by the company in a particular case reasonably related to (a) the seriousness of the employee’s proven offense and (b) the record of the employee in his service with the company?[1]

While this test is less applicable in the modern era where contract employment relationships are rare, it sheds light on the underlying considerations and rights created by employment contracts.

Contract-based employment has some benefits but it also has several major drawbacks. First, contracted employees may face more restrictions in changing their jobs. They often must provide some notice if they want to quit before their term ends and may face other penalties for doing so. Additionally, these contracts reduce the leverage employees have if they want to negotiate a higher salary or better benefits in the middle of their contract term. Finally, firms have significantly less flexibility to reduce their staffing levels based on their own needs and changes in the market.

Although employment by contract is rare in the modern United States economy, it still exists in some industries. Tenured professors, for example, have strong protections against being fired without just cause. Unionized employees may also receive some just cause protections if they have negotiated for them in a contract. In a recent decision, the 7th Circuit considered a situation where a union agreement provided its members with for cause protections, but the employer’s handbook did not.[2] Joshua Cheli was a computer systems administrative assistant at a local school district. He was also a member of a union that had an agreement with the district. The relevant language in the agreement read:

“An employee may be disciplined, suspended, and/or discharged for reasonable cause. Grounds for discharge and/or suspension shall include, but not be limited to, drunkenness or drinking or carrying intoxicating beverages on the job, possession or use of any controlled and/ or illegal drug, dishonesty, insubordination, incompetency, or negligence in the performance of duties.”

In addition to this agreement with the union, the district also had an employee handbook outlining its employment policies. The handbook stated: “Unless otherwise specifically provided, District employment is at-will, meaning that employment may be terminated by the District or employee at any time for any reason, other than a reason prohibited by law, or no reason at all.”

The court considered whether this language in the union agreement provided Cheli with for-cause protections, or whether the at-will language in the handbook instead applied. The district argued that the union agreement said an employee may be fired for reasonable cause but did not state that they could only be fired for cause. The court rejected this interpretation based on the detailed language in the union agreement explaining the protections afforded to its members. Thus, Cheli was a contract-based employee and could only be fired for reasonable cause, regardless of the language in the handbook. Cases like this show the importance of carefully considering the content of agreements with unions and employees, and how these agreements may modify other documents like an employment policy manual.

In addition to these modern examples of contract-based employment, benefits like severance packages and “golden parachutes” provide some of the same benefits as contractual employment relationships by discouraging firms from firing employees and by protecting those employees if they are fired. For example, as of March 2022, the CEO of Moderna stands to receive a package worth $922.5 million if he loses his job as a result of the company being sold. Benefits like this have a similar effect to employment contracts because they strongly discourage employers from discharging their employees.

13.1.2 Employment at Will

Employment at will is the most common form of employment relationship in the United States. Unlike a contracted employee, the two parties in an at-will relationship – the employer and employee – owe no duty to one another to continue the employment. A supervisor can fire an employee for nearly any reason, so long as it does not violate state or federal law. Similarly, an employee can quit at any time and for any reason.

There is a presumption of at-will employment in most states in the United States. For example, California Labor Code Section 2922 reads: “An employment, having no specified term, may be terminated at the will of either party on notice to the other.” Under this regime, the default state of employment contracts is at-will. Employers and employees are free to modify this presumption by including for-cause language in an agreement. Absent this language, however, courts will presume that an at-will relationship exists.

Remember that both at-will and contract-based employees generally work under the terms of an employment contract. In other words, simply signing a contract with an employee does not make someone a contract-based employee with for cause protections. The presence of either a fixed length of employment or for cause protections make someone into a contract-based employee, not the mere existence of a contract. Without this language, an employee – regardless of whether or not they have a contract with their employer – is presumed to be at-will.

Even at-will employees receive some protections when they are fired for wrongful or illegal reasons. These protections include:

Discharging an Employee for Refusing to Violate a Law. Most state courts recognize a public policy exception barring firms from firing an employee for refusing to violate the law. This exception most commonly applies to situations where a company does not want an employee to testify truthfully at trial. In one case, a nurse refused a doctor’s order to administer a certain anesthetic when she believed it was wrong for that particular patient; the doctor, angry at the nurse for refusing to obey him, then administered the anesthetic himself. The patient soon stopped breathing. The doctor and others could not resuscitate him soon enough, and he suffered permanent brain damage. When the patient’s family sued the hospital, the hospital told the nurse she would be in trouble if she testified. She did testify according to her oath in the court of law (i.e., truthfully), and after several months of harassment, was finally fired on a pretext. The hospital was held liable for the tort of wrongful discharge. As a general rule, you should not fire an employee for refusing to break the law.

Discharging an Employee for Exercising a Legal Right. Most state courts recognize a second, similar public policy exception preventing employers from firing an employee for exercising some legal right. Courts most commonly apply this exception to situations where an employee was fired for seeking workers’ compensation after being injured on the job. Suppose Bob Berkowitz files a claim for workers’ compensation for an accident at Pacific Gas & Electric, where he works and where the accident that injured him took place. He is fired for doing so, because the employer does not want to have its workers’ comp premiums increased. In this case, the right exercised by Berkowitz is supported by public policy: he has a legal right to file the claim, and if he can establish that their discharge was caused by their filing the claim, he will prove the tort of wrongful discharge.

Discharging an Employee for Performing a Legal Duty. Courts have long held that an employee may not be fired for performing a legal duty like serving on a jury. This is so even though courts do recognize that many employers have difficulty replacing employees called for jury duty. Jury duty is an important civic obligation, and employers are not permitted to undermine it.

Discharging an Employee in a Way That Violates Public Policy. In addition to the specific public policy protections listed here, some states recognize a broader protection against being fired in a way that violates public policy. This is the most controversial basis for a tort of wrongful discharge. A state’s public policy encapsulates the “basic social rights, duties, or responsibilities” of its citizens. However, there is an inherent vagueness to these terms that make them difficult to apply in practice. Like in contract law, courts most often look to statutes and case law for guidelines on public policy.

In Wagenseller v. Scottsdale Memorial Hospital, for example, a nurse who refused to “play along” with her coworkers on a rafting trip was discharged.[3] The group of coworkers had socialized at night and had been drinking alcohol. When the partying was near its peak, the plaintiff refused to be part of a group that performed nude actions to the tune of “Moon River” (a composition by Henry Mancini that was popular in the 1970s). The court, at great length, considered that “mooning” was a misdemeanor under Arizona law and that therefore her employer could not discharge her for refusing to violate a state law. Many courts that recognize the general public policy exception follow this practice of looking to state laws and regulations as a basis for finding a public policy.

Good Faith and Fair Dealing Standard. A few states, among them Massachusetts and California, have modified the at-will doctrine in a far-reaching way by holding that every employer has entered into an implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing with its employees. That means, the courts in these states say, that it is “bad faith” and therefore unlawful to discharge employees to avoid paying commissions or pensions due them. Under this implied covenant of fair dealing, any discharge without good cause—such as incompetence, corruption, or habitual tardiness—is actionable. This is not the majority view.

13.1.3 Independent Contractors

In addition to hiring employees on an at-will and contract basis, businesses frequently rely on the services of independent contractors. According to the Restatement (Second) of Agency, Section 2, “an independent contractor is a person who contracts with another to do something for him but who is not controlled by the other nor subject to the other’s right to control with respect to his physical conduct in the performance of the undertaking.”

Individuals participating in the “gig economy” are a commonly encountered example of independent contractors. People driving cars for Uber and delivering food for Door Dash retain high levels of independence and control. An Uber driver can begin and end work when she wants, accept or reject ride requests, and pick up customers in whatever area of the city she would like. Although Uber provides the means for a driver to connect with her customers, it leaves drivers with substantial amounts of autonomy that an employee would not have.

This distinction between employee and independent contractor has important legal consequences for taxation, workers’ compensation, and liability insurance. For example, employers are required to withhold income taxes from their employees’ paychecks. But payment to an independent contractor, such as a Grub Hub delivery driver, does not require such withholding.

Deciding who is an independent contractor is not always easy; there is no single factor or mechanical answer. In Robinson v. New York Commodities Corporation, an injured salesman sought workers’ compensation benefits, claiming to be an employee of the New York Commodities Corporation.[4] The state workmen’s compensation board concluded that he was an independent contractor, not an employee, and so he did not qualify for workers’ compensation. It took a holistic approach that can shed some light onto factors that distinguish an employee from an independent contractor. The claimant sold canned meats, making rounds in his car from his home. The company did not establish hours for him, did not control his movements in any way, and did not reimburse him for mileage or any other expenses or withhold taxes from its straight commission payments to him. He reported his taxes on a form for the self-employed and hired an accountant to prepare it for him. The court agreed with the compensation board that these facts established the salesman’s status as an independent contractor.

The facts specific to each case determines whether a worker is an employee or an independent contractor. Neither the company nor the worker can establish the worker’s status by agreement. As the North Dakota Workmen’s Compensation Bureau explained in a bulletin to real estate brokers, “It has come to the Bureau’s attention that many employers are requiring that those who work for them sign ‘independent contractor’ forms so that the employer does not have to pay workmen’s compensation premiums for his employees. Such forms are meaningless if the worker is in fact an employee.”[5]

Although distinguishing between an employee and independent contractor is often fact-specific, the right of control test is one helpful way to identify an independent contractor. Under this approach, a court will consider the extent of a business’s behavioral and financial control over an individual.

| Behavioral Control | Financial Control | |

| Independent Contractor | – Ability to decide when to work and how often to work

– Control or ownership over the equipment used to work – Minimal training provided by the business |

– Ability to set rates on a per-project or task basis

– No benefits like paid time off – Freedom to perform tasks for as many clients/ businesses as they want |

| Employee | – The business controls when and how often to come to work

– Little to no control or ownership over equipment – Training may be provided by the business |

– Paid hourly or on a salary basis

– Benefits such as sick leave, paid time off, or retirement plan – Limited ability to decide who to work for and what projects to accept |

13.2 Agency Relationships and Employment

An agent is a person who acts in the name of and on behalf of another, having been given and assumed some degree of authority to do so. The person or corporation the agent acts on behalf of is called the “principal.” Most organized human activity—and virtually all commercial activity—is carried on through agency. An agency relationship can be created by something as simple as a father giving his child money to go buy some milk from the store. In this scenario, the father is the principal and the child is ahis gent for the purposes of that trip. Another common example of agency is in professional sports. In this relationship, the athlete is the principal and her agent is responsible for helping her choose a team and negotiate favorable contracts with that team. Agents have a duty to work in the athlete’s best interest when performing this job.

No corporation would be possible, even in theory, without the concept of agency. We might say “General Motors is building cars in China,” for example, but General Motors itself cannot build cars or do business. “The General,” as people say, exists and works through agents. Likewise, partnerships and other business organizations rely extensively on agents to conduct their business. Indeed, it is not an exaggeration to say that agency is the cornerstone of enterprise organization. In a partnership each partner is a general agent, while under corporation law the officers and all employees are agents of the corporation.

The existence of agents does not, however, require a whole new law of torts or contracts. A tort is no less harmful when committed by an agent; a contract is no less binding when negotiated by an agent. What does need to be taken into account, though, is the manner in which an agent acts on behalf of his principal and toward a third party.

13.2.1 Creating Agency Relationships

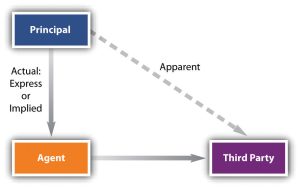

There are three basic ways in which agency power is granted: express authorization, implied authorization, and apparent authorization. Because employees and managers of a corporation serve as its agents, they act with one or more of these three types of authority on behalf of the business.

Express Authority (Agency Created by Agreement) The strongest form of authority is that which is expressly granted, often in written form. The principal consents to the agent’s actions, and the third party may then rely on the document attesting to the agent’s authority to deal on behalf of the principal. One common form of express authority340 is the standard signature card on file with banks allowing corporate agents to write checks on the company’s credit.

This express grant of authority is often part of a contract. In those cases the general rules of contract law covered in Chapter 8 apply. But agencies can also be created without contract, by agreement (for instance, without consideration, which not make the relationship contractual).

Implied Authority Implied authority exists to reasonably carry out the express authority granted to the agent. Not every detail of an agent’s work can be spelled out. It is impossible to delineate step-by-step the duties of a general agent; at best, a principal can set forth only the general nature of the duties that the agent is to perform. Even a special agent’s duties are difficult to describe in such detail as to leave him without discretion. If express authority were the only valid kind, there would be no efficient way to use an agent, both because the effort to describe the duties would be too great and because the third party would be reluctant to deal with him.

But the law permits authority to be “implied” by the relationship of the parties, the nature and customs of the business, the circumstances surrounding the act in question, the wording of the agency contract, and the knowledge that the agent has of facts relevant to the assignment. The general rule is that the agent has implied or “incidental” authority to perform acts incidental to or reasonably necessary to carrying out the transaction. Thus if a principal instructs her agent to “deposit a check in the bank today,” the agent has authority to drive to the bank unless the principal specifically prohibits the agent from doing so.

Apparent Authority In the agency relationship, the agent’s actions in dealing with third parties will affect the legal rights of the principal. What the third party knows about the agency agreement is irrelevant to the agent’s legal authority to act. That authority runs from principal to agent. As long as an agent has authorization, either express or implied, she may bind the principal legally. Thus the seller of a house may be ignorant of the buyer’s true identity; the person they suppose to be the prospective purchaser might be the agent of an undisclosed principal. Nevertheless, if the agent is authorized to make the purchase, the seller’s ignorance is not a ground for either seller or principal to void the deal.

But if a person has no authority to act as an agent, or an agent has no authority to act in a particular way, is the principal free from all consequences? The answer depends on whether or not the agent has apparent authority—that is, on whether or not the third person reasonably believes from the principal’s words, written or spoken, or from their conduct that they have in fact consented to the agent’s actions. Apparent authority is a manifestation of authority communicated to the third person; it runs from principal to third party, not to the agent.

Suppose Arthur is Paul’s agent, employed through October 31. On November 1, Arthur buys materials at Lumber Yard—as he has been doing since early spring—and charges them to Paul’s account. Lumber Yard, not knowing that Arthur’s employment terminated the day before, bills Paul. Will Paul have to pay? Yes, because the termination of the agency was not communicated to Lumber Yard. It appeared that Arthur was an authorized agent.

13.2.2 Fiduciary Duties in an Agency Relationship

In a nonagency contractual situation, the parties’ responsibilities terminate at the border of the contract. There is no relationship beyond the agreement. This literalist approach is justified by the more general principle that we each should be free to act unless we commit ourselves to a particular course.

But the agency relationship is more than a contractual one, and the agent’s responsibilities go beyond the border of the contract. Agency imposes a higher duty than simply to abide by the contract terms. It imposes a fiduciary duty. The law infiltrates the contract creating the agency relationship and reverses the general principle that the parties are free to act in the absence of agreement. As a fiduciary of the principal, the agent stands in a position of special trust. Their responsibility is to subordinate their self-interest to that of their principal. The fiduciary responsibility is imposed by law. The absence of any clause in the contract detailing the agent’s fiduciary duty does not relieve him of it. The duty contains several aspects: the agent or employee must avoid self-dealing, be loyal, be lawfully obedient, perform their tasks with reasonable skill and care, preserve confidential information, and so on.

The fiduciary duty does not run in reverse: the principal owes the agent general contractual duties but not fiduciary duties. Thus, the principal should, e.g., reimburse the agent for expenses but does not owe them a duty of loyalty. One particular duty of the employer is to provide workers’ compensation.

13.2.2.1 Worker’s Compensation. Alan, who works in a dynamite factory, negligently stores dynamite in the wrong shed. Alan warns his fellow employee Bill that he has done so. Bill lights up a cigarette near the shed anyway, a spark lands on the ground, the dynamite explodes, and Bill is injured. May Bill sue his employer to recover damages? At common law, the answer would be no—three times no. First, the “fellow-servant” rule would bar recovery because the employer was held not to be responsible for torts committed by one employee against another. Second, Bill’s failure to heed Alan’s warning and his decision to smoke near the dynamite amounted to contributory negligence. Hence even if the dynamite had been negligently stored by the employer rather than by a fellow employee, the claim would have been dismissed. Third, the courts might have held that Bill had “assumed the risk”: since he was aware of the dangers, it would not be fair to saddle the employer with the burden of Bill’s actions.

The three common-law rules just mentioned ignited intense public fury by the turn of the twentieth century. In large numbers of cases, workers who were mutilated or killed on the job found themselves and their families without recompense. Union pressure and grass roots lobbying led to workers’ compensation acts— statutory enactments that dramatically overhauled the law of torts as it affected employees.

Workers’ compensation is a no-fault system. The employee gives up the right to sue the employer (and, in some states, other employees) and receives in exchange predetermined compensation for a job-related injury, regardless of who caused it. This trade-off was felt to be equitable to employer and employee: the employee loses the right to seek damages for pain and suffering—which can be a sizable portion of any jury award—but in return they can avoid the time-consuming and uncertain judicial process and assure himself that their medical costs and a portion of their salary will be paid—and paid promptly. The employer must pay for all injuries, even those for which they are blameless, but in return they avoid the risk of losing a big lawsuit, can calculate their costs actuarially, and can spread the risks through insurance.

Most workers’ compensation acts provide 100 percent of the cost of a worker’s hospitalization and medical care necessary to cure the injury and relieve him from its effects. They also provide for payment of lost wages and death benefits. Even an employee who is able to work may be eligible to receive compensation for specific injuries.

Although workers’ compensation laws are on the books of every state, in two states—New Jersey and Texas—they are not compulsory. In those states the employer may decline to participate, in which event the employee must seek redress in court. But in those states permitting an employer election, the old common-law defenses (fellow-servant rule, contributory negligence, and assumption of risk) have been statutorily eliminated, greatly enhancing an employee’s chances of winning a suit. The incentive is therefore strong for employers to elect workers’ compensation coverage.

Those frequently excluded are farm and domestic laborers and public employees; public employees, federal workers, and railroad and shipboard workers are covered under different but similar laws. The trend has been to include more and more classes of workers. Approximately half the states now provide coverage for household workers, although the threshold of coverage varies widely from state to state. Some use an earnings test; other states impose an hours threshold. People who fall within the domestic category include maids, baby-sitters, gardeners, and handymen but generally not plumbers, electricians, and other independent contractors. In addition, independent contractors are not eligible for workers’ compensation because they are not employees of the firm.

Recurring legal issues in workers’ compensation include whether the injury was work related, whether the injured person was actually an employee, and whether psychological injury counts.

13.2.3 Agent and Principal Liability in Tort

Direct Liability. There is a distinction between torts prompted by the principal himself and torts of which the principal was innocent. If the principal directed the agent to commit a tort or knew that the consequences of the agent’s carrying out their instructions would bring harm to someone, the principal is liable. This is an application of the general common-law principle that one cannot escape liability by delegating an unlawful act to another. The syndicate that hires a hitman is as culpable of murder as the man who pulls the trigger. Similarly, a principal who is negligent in their use of agents will be held liable for their negligence. This rule comes into play when the principal fails to supervise employees adequately, gives faulty directions, or hires incompetent or unsuitable people for a particular job. Imposing liability on the principal in these cases is readily justifiable since it is the principal’s own conduct that is the underlying fault; the principal here is directly liable.

Vicarious Liability. But the principle of liability for one’s agent is much broader, extending to acts of which the principal had no knowledge, that they had no intention to commit nor involvement in, and that they may in fact have expressly prohibited the agent from engaging in. This is the principle of respondeat superior or the master-servant doctrine, which imposes on the principal vicarious liability347 (vicarious means “indirectly, as, by, or through a substitute”) under which the principal is responsible for acts committed by the agent within the scope of the employment.

The modern basis for vicarious liability is sometimes termed the “deep pocket” theory: the principal (usually a corporation) has deeper pockets than the agent, meaning that it has the wherewithal to pay for the injuries traceable one way or another to events it set in motion. A million-dollar industrial accident is within the means of a company or its insurer; it is usually not within the means of the agent—employee—who caused it.

In general, the broadest liability is imposed on the master in the case of tortious physical conduct by a servant or employee. If the servant or employee acted within the scope of their employment—that is, if the servant’s wrongful conduct occurred while performing their job—the master will be liable to the victim for damages unless, as we have seen, the victim was another employee, in which event the workers’ compensation system will be invoked. Vicarious tort liability is primarily a function of the employment relationship and not agency status.

Ordinarily, an individual or a company is not vicariously liable for the tortious acts of inde- pendent contractors. The plumber who rushes to a client’s house to repair a leak and causes a traffic accident does not subject the home- owner to liability. But there are exceptions to the rule. Generally, these exceptions fall into a category of duties that the law deems nondelegable. In some situations, one person is obligated to provide protection to or care for another. The failure to do so results in liability whether or not the harm befell the other because of an independent contractor’s wrongdoing. Thus a homeowner has a duty to ensure that physical conditions in and around the home are not unreasonably dangerous. If the owner hires an independent contracting firm to dig a sewer line and the contractor negligently fails to guard passersby against the danger of falling into an open trench, the homeowner is liable because the duty of care in this instance cannot be delegated. (The contractor is, of course, liable to the homeowner for any damages paid to an injured passerby.)

Liability for Agent’s Intentional Torts. In the nineteenth century, a principal was rarely held liable for intentional wrongdoing by the agent if the principal did not command the act complained of. The thought was that one could never infer authority to commit a willfully wrongful act. Today, liability for intentional torts is imputed to the principal if the agent is acting to further the principal’s business.

The general rule is that a principal is liable for torts only if the servant committed them “in the scope of employment.” But determining what this means is not easy.

It may be clear that the person causing an injury is the agent of another. But a principal cannot be responsible for every act of an agent. If an employee is following the letter of their instructions, it will be easy to determine liability. But suppose an agent deviates in some way from their job. The classic test of liability was set forth in an 1833 English case, Joel v. Morrison.[6] The plaintiff was run over on a highway by a speeding cart and horse. The driver was the employee of another, and inside was a fellow employee. There was no question that the driver had acted carelessly, but what they and their fellow employee were doing on the road where the plaintiff was injured was disputed. For weeks before and after the accident, the cart had never been driven in the vicinity in which the plaintiff was walking, nor did it have any business there. The suggestion was that the employees might have gone out of their way for their own purposes. As the great English jurist Baron Parke put it, “If the servants, being on their master’s business, took a detour to call upon a friend, the master will be responsible. But if he was going on a frolic of his own, without being at all on his master’s business, the master will not be liable.” In applying this test, the court held the employer liable.

The test is thus one of degree, and it is not always easy to decide when a detour has become so great as to be transformed into a frolic. For a time, a rather mechanical rule was invoked to aid in making the decision. The courts looked to the servant’s purposes in “detouring.” If the servant’s mind was fixed on accomplishing their own purposes, then the detour was held to be outside the scope of employment; hence the tort was not imputed to the master. But if the servant also intended to accomplish their master’s purposes during their departure from the letter of their assignment, or if they committed the wrong while returning to their master’s task after the completion of their frolic, then the tort was held to be within the scope of employment.

This test is not always easy to apply. If a hungry delivery driver stops at a restaurant outside the normal lunch hour, intending to continue to their next delivery after eating, they are within the scope of employment. But suppose they decide to take the truck home that evening, in violation of rules, in order to get an early start the next morning. Suppose they decide to stop by the beach, which is far away from the route. Does it make a difference if the employer knows that the driver do this?

Court decisions in the last forty years have moved toward a different standard, one that looks to the foreseeability of the agent’s conduct. By this standard, an employer may be held liable for their employee’s conduct even when devoted entirely to the employee’s own purposes, as long as it was foreseeable that the agent might act as he did. This is the “zone of risk” test. The employer will be within the zone of risk for vicarious liability if the employee is where she is supposed to be, doing—more or less—what she is supposed to be doing, and the incident arose from the employee’s pursuit of the employer’s interest (again, more or less). That is, the employer is within the zone of risk if the servant is in the place within which, if the master were to send out a search party to find a missing employee, it would be reasonable to look.

13.2.4 Agent and Principal Liability in Contract

The key to determining whether a principal is liable for contracts made by their agent is authority: was the agent authorized to negotiate the agreement and close the deal? Obviously, it would not be sensible to hold a contractor liable to pay for a whole load of lumber merely because a stranger wandered into the lumberyard saying, “I’m an agent for ABC Contractors; charge this to their account.” To be liable, the principal must have authorized the agent in some manner to act in their behalf, and that authorization must be communicated to the third party by the principal.

The agent will be liable in some cases as well. If the agent acted without authority, then they weren’t really acting as an agent and so will be personally liable for their contractual actions. If the third-party does not know the agent is acting for a principal (that is, if the principal is undisclosed), the third party will naturally sue the agent.349 For these reasons, agents who wish to avoid liability should always make it clear they are acting as agent for someone else. For example, an agent acting for a corporation in signing documents might wish their signature block to read “Jane Doe, Agent for BigCorp” or something similar. Finally, an agent acting in their personal capacity remains liable for their personal contracts.

Even if the agent possessed no actual authority and there was no apparent authority on which the third person could rely, the principal may still be liable if they ratify or adopt the agent’s acts before the third person withdraws from the contract. Ratification usually relates back to the time of the undertaking, creating authority after the fact as though it had been established initially. Ratification is a voluntary act by the principal. Faced with the results of action purportedly done on their behalf but without authorization and through no fault of their own, they may affirm or disavow them as they choose. To ratify, the principal may tell the parties concerned or by their conduct manifest that they are willing to accept the results as though the act were authorized. Or by their silence they may find under certain circumstances that they have ratified. Note that ratification does not require the usual consideration of contract law. The principal need be promised nothing extra for their decision to affirm to be binding. Nor does ratification depend on the position of the third party; for example, a loss stemming from their reliance on the agent’s representations is not required. In most situations, ratification leaves the parties where they expected to be, correcting the agent’s errors harmlessly and giving each party what was expected

- In re Enterprise Wire Company and Enterprise Independent Union, Decision of Arbitrator, March 28, 1966. ↵

- Cheli v. Taylorville Community School District, 7th Cir., No. 20-2033 (Feb. 3, 2021). ↵

- Wagenseller v. Scottsdale Memorial Hospital, 147 Ariz. 370; 710 P.2d 1025 (1085). ↵

- Robinson v. New York Commodities Corp., 396 N.Y.S.2d 725, App. Div. (1977). ↵

- Vizcaino v. Microsoft Corp, 120 F.3d 1006 (9th Cir. 1997). ↵

- Joel v. Morrison, 6 Carrington & Payne 501. ↵