1 Law and Risk Management

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, students should understand:

- The importance of legal risk management to business strategy

- How to assess attitude towards risk

- A simple model for assessing legal risk

- A preview of ways to manage and mitigate liability risks, such as through liquidated damages clauses and insurance

1.1 Introduction

Often, law for business students is taught as a sort of compressed version of law school. Subjects are taught much like they might be for law students, albeit at a simplified level. This sort of training can be useful, but it ignores a crucial difference between how lawyers and managers relate to the law: lawyers are trained to argue for specific legal conclusions on behalf of a client, while managers make decisions to manage legal risk. Law is rarely black and white, such as “don’t do this or you’ll go to jail.” Rather, legal decisions often involve questions such as “Our trademark is similar to several others. Is it too similar?” Or, “Adding this statement to the label of our product might expose us to liability, but it’s not prohibited by regulation. Should we proceed?” This leaves many managerial decisions involving law up to the risk tolerance of the manager. Compared to how attorneys operate, this requires a very different approach to legal reasoning. In this sense, a business-focused course on legal topics should essentially be a course on business strategy related to legal issues. It should equip managers with a broad overview of legal risks associated with running a business, how their decisions alter those risks, and how to minimize or otherwise use those risks to their advantage.

For these reasons, this text begins with a broad discussion of how one might evaluate risk generally. In this chapter, we will learn techniques for assessing, evaluating, and managing legal risks. Risk management is a topic for an entire course by itself, so in this chapter we will only touch on several major points and then apply them to the law. Throughout the course, examples and exercises will relate back to these concepts.

1.2 An Approach to Evaluating Risk

Risk management will be a major focal point of business and societal decision making in the twenty-first century. Businesses face an incredible variety of risks everyday, which range both in severity and in frequency. Some risks are minor (e.g., an employee might steal paperclips), and others may entail losing the business (a pandemic arises which eliminates demand for certain services). Some risks are frequent (bad weather for a drive-in movie theater), and some are infrequent (new government regulation alters the healthcare landscape). Legal risks span these same spectrums. Some legal risks are constant (potential slip and falls in a grocery store) and some are infrequent (a major intellectual property lawsuit). Some are minor (producing a product label well within regulatory standards) and some are significant (criminal negligence results in the death of customers).

In this section, we will discuss legal risk, which is one of a variety of these risks which businesses face everyday. As business increasingly involves international management, understanding legal risk has become more important than ever, due to the bewildering number of international norms and regulations governing the modern legal environment of business. The types of legal risk a company faces can be roughly broken down into four categories:[1]

- Regulatory risk. If a company fails to have appropriate compliance methods, it risks regulatory violations which can have far-reaching civil and criminal penalties.

- Tort risk. Companies that fail to take reasonable care to ensure the safety of their customers, clients, and employees will inevitably face personal injury lawsuits. Individuals injured on premises, industrial accidents, or products that harm customers may all result in litigation.

- Contract risk. Contracts are the language of business, and failure to understand contractual complexities may result in harmful liability. Competitors may take advantage of ambiguous terms, damages provisions may disfavor the company, or there may be unforeseen consequences from contractual provisions.

- Intellectual property risk. Modern business increasingly relies on intellectual property, rather than real property, to create value. Infringing on others’ intellectual property rights, or failure to protect one’s own intellectual property rights, can have substantial impact on a company.

Reading a long list of potential legal harms may inspire some trepidation, particularly for someone with responsibility over these areas of company operations. If we wish to understand and use the concepts of risk and uncertainty to manage these risks, we need to be able to measure (at least roughly) these concepts’ outcomes. Psychological and economic research shows that emotions such as fear, dread, ambiguity avoidance, and feelings of emotional loss represent valid risks. Such feelings are thus relevant to decision making under uncertainty. Our focus here, however, will draw more on financial metrics rather than emotional or psychological measures of risk perception.

We will discuss one particular approach to measuring risk here, which is a useful model in the legal context. We will not impose a mathematical framework on this model, for two reasons. First, this is a course on business law, not a course on statistics or probability models, and developing those models together would exceed the time available in this course. Second, and more foundational, assuming exact probabilities for potential legal events implies a level of certainty that will likely never exist in real life.

We also emphasize from the start that measuring risk using the model in this chapter is a multi-step process. We must evaluate how appropriate the underlying model might be for the specific occasion. Further, we need to evaluate each question in terms of the risk level that each entity is willing to assume for the gain each hopes to receive. Firms must understand the assumptions behind worst-case or ruin scenarios, since most firms do not want to take on risks that “bet the house.” To this end, knowing the severity of losses that might be expected in the future is a first step (legal consequences). However, financial decision making requires that we evaluate severity levels based upon what an individual or a firm can comfortably endure (attitudes towards risk, risk tolerance, or risk appetite).

1.3 Legal Consequences

Mismanaging legal risk can have a variety of consequences, from harm to reputation to imprisonment of company officers. These consequences range dramatically from minor to severe. Most of the consequences we will look at in this textbook are civil in nature. Civil cases involve one party suing another to seek compensation for a wrong. Damages can be compensatory (to put someone in the same position as if they had not been harmed) or punitive (intended to punish wrongdoing). If you are sued, you should also expect to spend a substantial amount on attorney fees, regardless of whether you win or lose.[2] On the civil side, courts can also impose injunctions, which is an order to perform, or not perform, a specific action.

If the financial consequences are severe enough, the firm might risk bankruptcy. Bankruptcy law governs the rights of creditors and insolvent debtors who cannot pay their debts. In broadest terms, bankruptcy deals with the seizure of the debtor’s assets and their distribution to the debtor’s various creditors. In bankruptcy, the firm might be liquidated or reorganized. As we will see later in the text, bankruptcy provides debtors a fresh start, but for many firms the consequences of bankruptcy are severe enough that they will avoid actions that likely lead to bankruptcy.

1.4 Attitudes Towards Risk

Different people and companies can view the legal risks above very differently. Some individuals do not mind the prospect of personal bankruptcy, for instance, and some companies are structured to take substantial risk. Others view the prospect of being sued with trepidation. In other words, different people and firms have different attitudes toward the risk-return tradeoff. People are risk averse when they shy away from risks and prefer to have as much security and certainty as is reasonably affordable in order to lower their discomfort level. They would be willing to pay extra to have the security of knowing that unpleasant risks would be removed from their lives. Economists and risk management professionals consider most people to be risk averse. So, why do people invest in the stock market where they confront the possibility of losing everything? Perhaps they are also seeking the highest value possible for their pensions and savings and believe that losses may not be pervasive—very much unlike the situation in the financial crisis of 2008.

A risk seeker, on the other hand, is not simply the person who hopes to maximize the value of retirement investments by investing the stock market. Much like a gambler, a risk seeker is someone who will enter into an endeavor (such as blackjack card games or slot machine gambling) as long as a positive long run return on the money is possible, however unlikely.

Finally, an entity is said to be risk neutral when its risk preference lies in between these two extremes. Risk neutral individuals will not pay extra to have the risk transferred to someone else, nor will they pay to engage in a risky endeavor. To them, money is money. Economists consider most widely held or publicly traded corporations as making decisions in a risk-neutral manner since their shareholders have the ability to diversify away risk—to take actions that seemingly are not related or have opposite effects, or to invest in many possible unrelated products or entities such that the impact of any one event decreases the overall risk. Risks that the corporation might choose to transfer remain for diversification.

1.5 A Model for Evaluating Legal Risk

This section combines the ideas from the prior sections to implement a simple, non-mathematical model for evaluating legal risk. A “model” is a simplified framework for evaluating a real-life situation. It will never capture all of the nuance involved in a particular choice, but it may be useful to decisionmakers. In particular, the model presented here is non-mathematical. It relies on simple categorization of the likelihood of an event, the consequences of that event, and the decisionmaker’s approach to evaluating risk.

First, evaluate the likelihood of the event. For instance, what are the chances of getting sued? We will categorize the likelihood as “low”, “medium”, or “high”. Much of this course will aim to teach you how to categorize potential legal events in this framework. For example, as we study intellectual property law you will gain a sense of the likelihood of being sued based on similarity of your trademark to existing trademarks, and as we study tort law you will get a sense for which torts are common and uncommon. We won’t use specific probabilities for these events in formal calculations, but you might think of a low probability event as one that rarely occurs for similar companies, a medium probability event as one that has occurred several times in the last year for similar companies, and a high probability event as one which will almost certainly result in litigation.

Next, categorize the severity of the outcome as “slight”, “manageable”, or “severe”. Again, much of this course aims to teach you which events are which. As you did the Exercise under “Legal Consequences” above, you likely started to see some of the newsworthy severe events faced by firms in your industry. For modeling purposes, a slight outcome is one which would not harm the financial health of the company in a significant way. An example might be a somewhat frivolous lawsuit which is settled as a “nuisance suit” for a few thousand dollars.[3] A manageable outcome is one which would generate discussion among managers about potential budgets for a loss, such as a small-business customer injured in an accident with major medical bills. This kind of outcome might worry managers, but does not risk the future of the business. A severe outcome is one which risks bankruptcy, criminal charges, or other substantial long-term consequences for the existence of the firm.

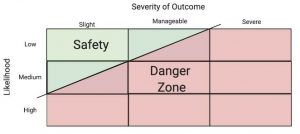

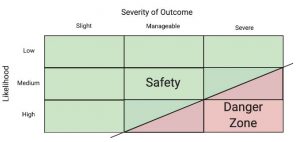

Finally, decide the correct attitude towards risk. Is the firm risk averse, risk neutral, or risk seeking? In our model, the attitude towards risk forms the shaded “danger zone” in the grid, dividing causes of little concern from significant concern. The more risk averse the individual or firm, the farther up and to the left we shift the dividing line, and the more risk-seeking the firm, the farther lower and to the right we shift the line. An extremely risk averse firm would avoid even low probability severe events (as shown in the first figure below), while an extremely risk-seeking firm might avoid only high probability severe events.

Applying this model might look something like the following. We (1) classify the likelihood of the legal event, and (2) the severity of the consequence. Then (3), we identify the risk tolerance of the firm. Finally, (4) we analyze how those three interact and offer a conclusion: is this a high risk decision, in the legal danger zone, or a low risk decision, in the zone of safety?

A highly risk averse firm avoids the possibility of severe legal outcomes.

A risk seeking firm might avoid only the most likely and severe legal consequences.

For example, suppose the firm under consideration is a tech startup like Uber. The firm consistently pushes legal boundaries, such as in classifying workers as independent contractors rather than employees, as it attempts to increase market share in a quickly growing industry.[4] Suppose also that the firm was considering whether to expand to a city that has somewhat hostile regulations for ride-sharing. At the same time, the consequences for entering the market and losing a legal challenge are simply to withdraw or pay an insubstantial fine. Let’s apply the model:

-

- As the new market appears hostile, the likelihood of legal challenge is probably medium or high.

- Relative to the size of the firm, a modest fine is a relatively small consequence. We might then classify the severity of outcome as low.

- We might classify this firm as risk seeking based on its past attitude towards the law and the potential rewards at stake.

- Although the likelihood of legal action is moderate to high, the potential consequence is slight. This decision is likely a low-risk legal decision, in the legal safety zone for the firm.

1.6 Mitigating and Managing Legal Risk

We conclude this chapter by highlighting methods to mitigate legal risk. We will cover many of these topics in greater detail later, but it is worth noting them in abbreviated form now, both to round off this initial topic and to preview what we will study throughout the semester.

- Insurance. Both individuals and businesses have significant needs for various types of insurance, to provide protection for health care, for their property, and for legal claims made against them by others. Insurance allows individuals to pay a certain amount today to avoid uncertain losses in the future. Businesses face a host of risks that could result in substantial liabilities. Many types of policies are available, including policies for owners, landlords, and tenants (covering liability incurred on the premises); for manufacturers and contractors (for liability incurred on all premises); for a company’s products and completed operations (for liability that results from warranties on products or injuries caused by products); for owners and contractors (protective liability for damages caused by independent contractors engaged by the insured); and for contractual liability (for failure to abide by performances required by specific contracts). Some years ago, different types of individual and business coverage had to be purchased separately and often from different companies. Today, most insurance is available on a package basis, through single policies that cover the most important risks. These are often called multiperil policies.

- Smart contracting. As we will study in contract law later in this text, in order to limit risk in contracts, many contractual drafters choose to include “liquidated damages” clauses. These are statements in the contract that spell out what damages will be if the contract is broken. This makes the damages certain, which lowers risk for the contracting parties. For example, in a contract for sale of a home, a party might lose their “ready money” if they back out of the agreement without cause.

- Regulatory review. Many firms find it worthwhile to preemptively hire an attorney to review products for regulatory and litigation risk before launching the product. For a fee, a specialized attorney can examine the product and provide a report on potential regulatory violations and lawsuit risks. Many firms might be surprised at the substantial increased risk of litigation based on innocuous statements on packaging, for instance. We will return to this theme when we cover administrative law (the law of government regulation of business).

- Preemptive tort defense. The liberal use of liability waivers, warning labels, caution signs, safety rails, handguards, and so on, can help prevent against tort litigation. Liability waivers reduce litigation risk by having individuals specifically agree they will not sue in case of injury during an activity. In other cases, often such litigation turns not on whether someone was injured from a product, but whether they were appropriately warned that such injury could occur. Physical safeguards against injury can help reduce the probability of potential negligence lawsuits by preventing injury in the first place. Businesses that practice prudent preemptive tort defense can lower their legal risks substantially.

- Limited liability forms When starting a new business, choosing a legal structure for the company that provides a personal liability shield substantially lowers legal risk for the proprietor. Then, performing business operations in a way that maintains that liability shield continues to lower legal risk. For corporations and franchisors, maintaining appropriate relationships with subsidiaries and franchisees provides the same benefit. For example, if a franchisor exercises excessive control over franchisee operations, it opens itself up to liability for the franchisee’s actions.

- A risk-educated board In corporations, the board of directors has the primary legal responsibility to manage risk. If a board is risk-educated, it will incorporate legal risk management into its overall strategy for the company. One path to strategic success is pursuing opportunities in which the corporation can manage legal risk better than competitors.[5]

- Knowing the law. Finally, a prime way to reduce legal risk is to simply be familiar with the law. An attorney will not always be around to consult, or it may be cost-prohibitive to use their services at times. Law is vast and complicated, but many legal concepts foundational to business are easy to understand. The more one knows about the law, the easier it is to avoid compromising legal situations, to be conversant with those that can offer legal counsel, and to make decisions that balance legal and ethical interests with other strategic concerns.

Key Takeaways

- Approaching law from a risk management approach is crucial to evaluate the legal

environment of business. - Evaluating legal risk requires understanding the likelihood of legal action, the

severity of the consequences, and the risk tolerance level of the company. Even low

probability legal events can be so severe that risk averse firms should take action

to avoid them, while even high probability legal events may not bother risk seeking

firms. - Much of this text will offer ways to reduce legal risk associated with business decisions,

such as preemptively avoiding tort liability and employing smart contracting

principles. Insurance against legal claims can also reduce uncertainty, at a price.

- Adapted from Matthew Whalley and Chris Guzelian, The Legal Risk Management Handbook: An Interntional Guide to Protect Your Business from Legal Loss (2017). ↵

- Courts will sometimes grant attorneys’ fees, but this is not typical of litigation in the United States. ↵

- 3A nuisance suit is one with little legal merit, which a company will pay a small sum to settle to avoid the costs of litigation. ↵

- They might also be classified as risk-neutral because the company simply finds it advantageous to engage in legally risky behavior. ↵

- See Roger Barker et al., Risk Management and the Board of Directors: Lessons to be Learned from USB, in Legal Risk Management, Governance, and Corporate Compliance 174 (2013). ↵