10 Products Liability

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should understand the following:

- How products-liability law allocates the costs of a consumer society.

- How warranty theory works in products liability, and what its limitations are.

- How negligence theory works, and what its problems are.

- How strict liability theory works, and what its limitations are.

- What efforts are made to reform products-liability law, and why.

10.1 Introduction: Why Products-Liability Law Is Important

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to do the following:

- Understand why products-liability law underwent a revolution in the twentieth century.

- Recognize that courts play a vital role in policing the free enterprise system by adjudicating how the true costs of modern consumer culture are allocated.

- Know the names of the modern causes of action for products-liability cases.

In previous chapters, we discussed contract and tort remedies for various types of injury. In this chapter, we focus specifically on remedies available when a defective product causes personal injury or other damages. Products liability describes a type of claim, not a separate theory of liability. Products liability has strong emotional overtones—ranging from the prolitigation position of consumer advocates to the conservative perspective of the manufacturers.

10.1.1 History of Products-Liability Law

The theory of caveat emptor—let the buyer beware—that pretty much governed consumer law from the early eighteenth century until the early twentieth century made some sense. A horse-drawn buggy is a fairly simple device: its workings are apparent; a person of average experience in the 1870s would know whether it was constructed well and made of the proper woods. Most foodstuffs 150 years ago were grown at home and “put up” in the home kitchen or bought in bulk from a local grocer, subject to inspection and sampling; people made home remedies for coughs and colds and made many of their own clothes. Houses and furnishings were built of wood, stone, glass, and plaster—familiar substances. Entertainment was a book or a piano. The state of technology was such that the things consumed were, for the most part, comprehensible and—very important—mostly locally made, which meant that the consumer who suffered damages from a defective product could confront the product’s maker directly. Local reputation is a powerful influence on behavior.

The free enterprise system confers great benefits, and no one can deny that: materialistically, compare the image sketched in the previous paragraph with circumstances today. But those benefits come with a cost, and the fundamental political issue always is who has to pay. Consider the following famous passage from Upton Sinclair’s novel The Jungle. It appeared in 1906. He wrote it to inspire labor reform; to his dismay, the public outrage focused instead on consumer protection reform. Here is his description of the sausage-making process in a big Chicago meatpacking plant:

It became clear from Sinclair’s exposé that associated with the marvels of then-modern meatpacking and distribution methods was food poisoning: a true cost became apparent. When the true cost of some money-making enterprise (e.g., cigarettes) becomes inescapably apparent, there are two possibilities. First, the legislature can in some way mandate that the manufacturer itself pay the cost; with the meatpacking plants, that would be the imposition of sanitary food-processing standards.

It became clear from Sinclair’s exposé that associated with the marvels of then-modern meatpacking and distribution methods was food poisoning: a true cost became apparent. When the true cost of some money-making enterprise (e.g., cigarettes) becomes inescapably apparent, there are two possibilities. First, the legislature can in some way mandate that the manufacturer itself pay the cost; with the meatpacking plants, that would be the imposition of sanitary food-processing standards.

Typically, Congress creates an administrative agency and gives the agency some marching orders, and then the agency crafts regulations dictating as many industry-wide reform measures as are politically possible. Second, the people who incur damages from the product (1) suffer and die or (2) access the machinery of the legal system and sue the manufacturer. If plaintiffs win enough lawsuits, the manufacturer’s insurance company raises rates, forcing reform (as with high-powered muscle cars in the 1970s); the business goes bankrupt; or the legislature is pressured to act, either for the consumer or for the manufacturer.

If the industry has enough clout to blunt—by various means—a robust proconsumer legislative response so that government regulation is too lax to prevent harm, recourse is had through the legal system. Thus for all the talk about the need for tort reform (discussed later in this chapter), the courts play a vital role in policing the free enterprise system by adjudicating how the true costs of modern consumer culture are allocated.

Obviously the situation has improved enormously in a century, but one does not have to look very far to find terrible problems today.[2]

Products liability can also be a life-or-death matter from the manufacturer’s perspective. In 2009, Bloomberg BusinessWeek reported that the costs of product safety for manufacturing firms can be enormous: “Peanut Corp., based in Lynchberg, Va., has been driven into bankruptcy since health officials linked tainted peanuts to more than 600 illnesses and nine deaths. Mattel said the first of several toy recalls it announced in 2007 cut its quarterly operating income by $30 million. Earlier this decade, Ford Motor spent roughly $3 billion replacing 10.6 million potentially defective Firestone tires.”[3]

10.1.2 Current State of the Law

Although the debate has been heated and at times simplistic, the problem of products liability is complex and most of us regard it with a high degree of ambivalence. We are all consumers, after all, who profit greatly from living in an industrial society. In this chapter, we examine the legal theories that underlie products-liability cases that developed rapidly in the twentieth century to address the problems of product-caused damages and injuries in an industrial society.

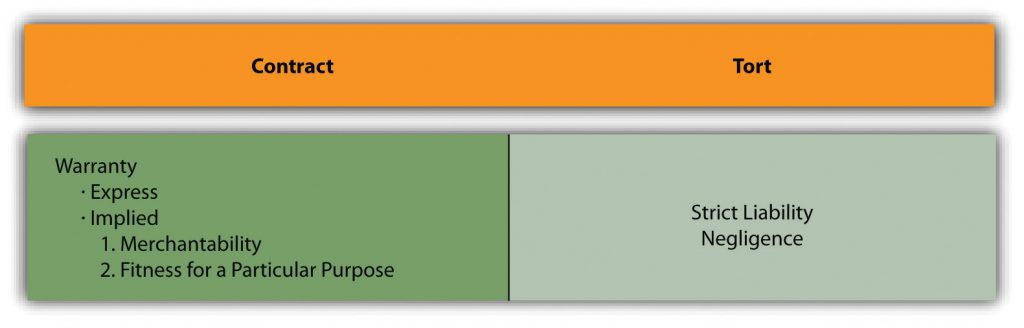

In the typical products-liability case, three legal theories are asserted—a contract theory and two tort theories. The contract theory is warranty[4], governed by the UCC, and the two tort theories are negligence[5] and strict products liability[6], governed by the common law.

Key Takeaway

As products became increasingly sophisticated and potentially dangerous in the twentieth century, and as the separation between production and consumption widened, products liability became a very important issue for both consumers and manufacturers. Millions of people every year are adversely affected by defective products, and manufacturers and sellers pay huge amounts for products-liability insurance and damages. The law has responded with causes of action that provide a means for recovery for products-liability damages.

10.2 Warranties

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to do the following:

- Recognize a UCC express warranty and how it is created.

- Understand what is meant under the UCC by implied warranties, and know the main types of implied warranties: merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, and title.

- Know that there are other warranties: against infringement and as may arise from usage of the trade.

- See that there are difficulties with warranty theory as a cause of action for products liability; a federal law has addressed some of these.

The UCC governs express warranties and various implied warranties, and for many years it was the only statutory control on the use and meanings of warranties. In 1975, after years of debate, Congress passed and President Gerald Ford signed into law the Magnuson-Moss Act, which imposes certain requirements on manufacturers and others who warrant their goods. We will examine both the UCC and the Magnuson-Moss Act.

10.2.1 Types of Warranties

10.2.1.1 Express Warranties An express warranty[7] is created whenever the seller affirms that the product will perform in a certain manner. Formal words such as “warrant” or “guarantee” are not necessary. A seller may create an express warranty as part of the basis for the bargain of sale by means of (1) an affirmation of a fact or promise relating to the goods, (2) a description of the goods, or (3) a sample or model. Any of these will create an express warranty that the goods will conform to the fact, promise, description, sample, or model. Thus a seller who states that “the use of rustproof linings in the cans would prevent discoloration and adulteration of the Perform solution” has given an express warranty, whether he realized it or not.[8] Claims of breach of express warranty are, at base, claims of misrepresentation.

But the courts will not hold a manufacturer to every statement that could conceivably be interpreted to be an express warranty. Manufacturers and sellers constantly “puff” their products, and the law is content to let them inhabit that gray area without having to make good on every claim. UCC 2-313(2) says that “an affirmation merely of the value of the goods or a statement purporting to be merely the seller’s opinion or commendation of the goods does not create a warranty.” Facts do.

It is not always easy, however, to determine the line between an express warranty and a piece of puffery. A salesperson who says that a strawberry huller is “great” has probably puffed, not warranted, when it turns out that strawberries run through the huller look like victims of a massacre. But consider the classic cases of the defective used car and the faulty bull. In the former, the salesperson said the car was in “A-1 shape” and “mechanically perfect.”

It is not always easy, however, to determine the line between an express warranty and a piece of puffery. A salesperson who says that a strawberry huller is “great” has probably puffed, not warranted, when it turns out that strawberries run through the huller look like victims of a massacre. But consider the classic cases of the defective used car and the faulty bull. In the former, the salesperson said the car was in “A-1 shape” and “mechanically perfect.”

In the latter, the seller said not only that the bull calf would “put the buyer on the map” but that “his father was the greatest living dairy bull.” The car, carrying the buyer’s seven-month-old child, broke down while the buyer was en route to visit her husband in the army during World War II. The court said that the salesperson had made an express warranty.[9] The bull calf turned out to be sterile, putting the farmer on the judicial rather than the dairy map. The court said the seller’s spiel was trade talk, not a warranty that the bull would impregnate cows.[10]

Is there any qualitative difference between these decisions, other than the quarter century that separates them and the different courts that rendered them? Perhaps the most that can be said is that the more specific and measurable the statement’s standards, the more likely it is that a court will hold the seller to a warranty, and that a written statement is easier to construe as a warranty than an oral one. It is also possible that courts look, if only subliminally, at how reasonable the buyer was in relying on the statement, although this ought not to be a strict test. A buyer may be unreasonable in expecting a car to get 100 miles to the gallon, but if that is what the seller promised, that ought to be an enforceable warranty.

10.2.1.2 Implied Warranties Express warranties are those over which the parties dickered— or could have. Express warranties go to the essence of the bargain. An implied warranty[11], by contrast, is one that circumstances alone, not specific language, compel reading into the sale. In short, an implied warranty is one created by law, acting from an impulse of common sense.

10.2.1.2.1 Implied Warranty of Merchantability Section 2-314 of the UCC lays down the fundamental rule that goods carry an implied warranty of merchantability. What is merchantability? Section 2-314(2) of the UCC says that merchantable goods are those that conform at least to the following six characteristics:

- Pass without objection in the trade under the contract description

- In the case of fungible goods, are of fair average quality within the description

- Are fit for the ordinary purposes for which such goods are used

- Run, within the variations permitted by the agreement, of even kind, quality, and quantity within each unit and among all units involved

- Are adequately contained, packaged, and labeled as the agreement may require

- Conform to the promise or affirmations of fact made on the container or label if any

For the purposes of Section 2-314(2)(c) of the UCC, selling and serving food or drink for consumption on or off the premises is a sale subject to the implied warranty of merchantability—the food must be “fit for the ordinary purposes” to which it is put. The problem is common: you bite into a cherry pit in the cherry-vanilla ice cream, or you choke on the clam shells in the chowder. Is such food fit for the ordinary purposes to which it is put? There are two schools of thought. One asks whether the food was natural as prepared. This view adopts the seller’s perspective. The other asks what the consumer’s reasonable expectation was.

For the purposes of Section 2-314(2)(c) of the UCC, selling and serving food or drink for consumption on or off the premises is a sale subject to the implied warranty of merchantability—the food must be “fit for the ordinary purposes” to which it is put. The problem is common: you bite into a cherry pit in the cherry-vanilla ice cream, or you choke on the clam shells in the chowder. Is such food fit for the ordinary purposes to which it is put? There are two schools of thought. One asks whether the food was natural as prepared. This view adopts the seller’s perspective. The other asks what the consumer’s reasonable expectation was.

The first test is sometimes said to be the “natural-foreign” test. If the substance in the soup is natural to the substance—as bones are to fish—then the food is fit for consumption. The second test, relying on reasonable expectations, tends to be the more commonly used test.

10.2.1.3 Fitness for a Particular Purpose Section 2-315 of the UCC creates another implied warranty. Whenever a seller, at the time she contracts to make a sale, knows or has reason to know that the buyer is relying on the seller’s skill or judgment to select a product that is suitable for the particular purpose the buyer has in mind for the goods to be sold, there is an implied warranty that the goods are fit for that purpose. For example, you go to a hardware store and tell the salesclerk that you need a paint that will dry overnight because you are painting your front door and a rainstorm is predicted for the next day. The clerk gives you a slow-drying oil-based paint that takes two days to dry. The store has breached an implied warranty of fitness for particular purpose.[12]

Note the distinction between “particular” and “ordinary” purposes. Paint is made to color and when dry to protect a surface. That is its ordinary purpose, and had you said only that you wished to buy paint, no implied warranty of fitness would have been breached. It is only because you had a particular purpose in mind that the implied warranty arose. Suppose you had found a can of paint in a general store and told the same tale, but the proprietor had said, “I don’t know enough about that paint to tell you anything beyond what’s on the label; help yourself.” Not every seller has the requisite degree of skill and knowledge about every product he sells to give rise to an implied warranty. Ultimately, each case turns on its particular circumstances.

Note the distinction between “particular” and “ordinary” purposes. Paint is made to color and when dry to protect a surface. That is its ordinary purpose, and had you said only that you wished to buy paint, no implied warranty of fitness would have been breached. It is only because you had a particular purpose in mind that the implied warranty arose. Suppose you had found a can of paint in a general store and told the same tale, but the proprietor had said, “I don’t know enough about that paint to tell you anything beyond what’s on the label; help yourself.” Not every seller has the requisite degree of skill and knowledge about every product he sells to give rise to an implied warranty. Ultimately, each case turns on its particular circumstances.

10.2.1.4 Other Warranties Article 2 contains other warranty provisions, though these are not related specifically to products liability. Thus, under UCC, Section 2-312, unless explicitly excluded, the seller warrants he is conveying good title that is rightfully his and that the goods are transferred free of any security interest or other lien or encumbrance. In some cases (e.g., a police auction of bicycles picked up around campus and never claimed), the buyer should know that the seller does not claim title in himself, nor that title will necessarily be good against a third party, and so subsection (2) excludes warranties in these circumstances. But the circumstances must be so obvious that no reasonable person would suppose otherwise.

In Menzel v. List, an art gallery sold a painting by Marc Chagall that it purchased in Paris.[13] The painting had been stolen by the Germans when the original owner was forced to flee Belgium in the 1930s. Now in the United States, the original owner discovered that a new owner had the painting and successfully sued for its return. The customer then sued the gallery, claiming that it had breached the implied warranty of title when it sold the painting. The court agreed and awarded damages equal to the appreciated value of the painting. A good-faith purchaser who must surrender stolen goods to their true owner has a claim for breach of the implied warranty of title against the person from whom he bought the goods.

A second implied warranty, related to title, is that the merchant-seller warrants the goods are free of any rightful claim by a third person that the seller has infringed his rights (e.g., that a gallery has not infringed a copyright by selling a reproduction). This provision only applies to a seller who regularly deals in goods of the kind in question. If you find an old print in your grandmother’s attic, you do not warrant when you sell it to a neighbor that it is free of any valid infringement claims.

A third implied warranty in this context involves the course of dealing or usage of trade. Section 2-314(3) of the UCC says that unless modified or excluded implied warranties may arise from a course of dealing or usage of trade. If a certain way of doing business is understood, it is not necessary for the seller to state explicitly that he will abide by the custom; it will be implied. A typical example is the obligation of a dog dealer to provide pedigree papers to prove the dog’s lineage conforms to the contract.

10.2.2 Problems with Warranty Theory

10.2.2.1 In General It may seem that a person asserting a claim for breach of warranty will have a good chance of success under an express warranty or implied warranty theory of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. In practice, though, claimants are in many cases denied recovery. Here are four general problems:

10.2.2.1 In General It may seem that a person asserting a claim for breach of warranty will have a good chance of success under an express warranty or implied warranty theory of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. In practice, though, claimants are in many cases denied recovery. Here are four general problems:

- The claimant must prove that there was a sale.

- The sale was of goods rather than real estate or services.

- The action must be brought within the four-year statute of limitations under Article 2-725, when the tender of delivery is made, not when the plaintiff discovers the defect.

- Under UCC, Section 2-607(3)(a) and Section 2A-516(3)(a), which covers leases, the claimant who fails to give notice of breach within a reasonable time of having accepted the goods will see the suit dismissed, and few consumers know enough to do so, except when making a complaint about a purchase of spoiled milk or about paint that wouldn’t dry.

In addition to these general problems, the claimant faces additional difficulties stemming directly from warranty theory, which we take up later in this chapter.

10.2.2.2 Exclusion or Modification of Warranties The UCC permits sellers to exclude or disclaim warranties in whole or in part. That’s reasonable, given that the discussion here is about contract, and parties are free to make such contracts as they see fit. But a number of difficulties can arise.

10.2.2.3 Exclusion of Express Warranties The simplest way for the seller to exclude express warranties is not to give them. To be sure, Section 2-316(1) of the UCC forbids courts from giving operation to words in fine print that negate or limit express warranties if doing so would unreasonably conflict with express warranties stated in the main body of the contract—as, for example, would a blanket statement that “this contract excludes all warranties express or implied.” The purpose of the UCC provision is to prevent customers from being surprised by unbargained-for language.

10.2.2.4 Exclusion of Implied Warranties in General Implied warranties can be excluded easily enough also, by describing the product with language such as “as is” or “with all faults.” Nor is exclusion simply a function of what the seller says. The buyer who has either examined or refused to exam- ine the goods before entering into the contract may not assert an implied warranty concerning defects an inspection would have revealed.

10.2.2.5 Implied Warranty of Merchantability Section 2-316(2) of the UCC permits the seller to disclaim or modify the implied warranty of merchantability, as long as the statement actually mentions “merchantability” and, if it is written, is “conspicuous.” Note that the disclaimer need not be in writing, and—again—all implied warranties can be excluded as noted.

10.2.2.6 Implied Warranty of Fitness Section 2-316(2) of the UCC permits the seller also to disclaim or modify an implied warranty of fitness. This disclaimer or modification must be in writing, however, and must be conspicuous. It need not mention fitness explicitly; general language will do. The following sentence, for example, is sufficient to exclude all implied warranties of fitness: “There are no warranties that extend beyond the description on the face of this contract.”

Here is a standard disclaimer clause found in a Dow Chemical Company agreement: “Seller warrants that the goods supplied here shall conform to the description stated on the front side hereof, that it will convey good title, and that such goods shall be delivered free from any lawful security interest, lien, or encumbrance. SELLER MAKES NO WARRANTY OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR USE. NOR IS THERE ANY OTHER EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTY.”

10.2.2.7 Conflict between Express and Implied Warranties Express and implied warranties and their exclusion or limitation can often conflict. Section 2-317 of the UCC provides certain rules for deciding which should prevail. In general, all warranties are to be construed as consistent with each other and as cumulative. When that assumption is unreasonable, the parties’ intention governs the interpretation, according to the following rules: (a) exact or technical specifications displace an inconsistent sample or model or general language of description; (b) a sample from an existing bulk displaces inconsistent general language of description; (c) express warranties displace inconsistent implied warranties other than an implied warranty of fitness for a particular purpose. Any inconsistency among warranties must always be resolved in favor of the implied warranty of fitness for a particular purpose. This doesn’t mean that warranty cannot be limited or excluded altogether. The parties may do so. But in cases of doubt whether it or some other language applies, the implied warranty of fitness will have a superior claim.

10.2.2.8 The Magnuson-Moss Act and Phantom Warranties After years of debate over extending federal law to regulate warranties, Congress enacted the Magnuson-Moss Federal Trade Commission Warranty Improvement Act (more commonly referred to as the Magnuson- Moss Act) and President Ford signed it in 1975. The act was designed to clear up confusing and misleading warranties, where—as Senator Magnuson put it in introducing the bill—“purchasers of consumer products discover that their warranty may cover a 25-cent part but not the $100 labor charge or that there is full coverage on a piano so long as it is shipped at the purchaser’s expense to the factory. There is a growing need to generate consumer understanding by clearly and conspicuously disclosing the terms and conditions of the warranty and by telling the consumer what to do if his guaranteed product becomes defective or malfunctions.” The Magnuson-Moss Act only applies to consumer products (for household and domestic uses); commercial purchasers are presumed to be knowledgeable enough not to need these protections, to be able to hire lawyers, and to be able to include the cost of product failures into the prices they charge.

The act has several provisions to meet these consumer concerns; it regulates the content of warranties and the means of disclosing those contents. The act gives the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) the authority to promulgate detailed regulations to interpret and enforce it. Under FTC regulations, any written warranty for a product costing a consumer more than ten dollars must disclose in a single document and in readily understandable language a variety of information items, such as a statement of when the warranty period starts and expires, how the consumer can utilize informal dispute mechanisms, etc.

In addition to these requirements, the act requires that the warranty be labeled either a full or limited warranty. A full warranty[14] means (1) the defective product or part will be fixed or replaced for free, including removal and reinstallation; (2) it will be fixed within a reasonable time; (3) the consumer need not do anything unreasonable (like shipping the piano to the factory) to get warranty service; (4) the warranty is good for anyone who owns the product during the period of the warranty; (5) the consumer gets money back or a new product if the item cannot be fixed within a reasonable number of attempts. But the full warranty may not cover the whole product: it may cover only the hard drive in the computer, for example; it must state what parts are included and excluded. A limited warranty[15] is less inclusive. It may cover only parts, not labor; it may require the consumer to bring the product to the store for service; it may impose a handling charge; it may cover only the first purchaser. Both full and limited warranties may exclude consequential damages.

Disclosure of the warranty provisions prior to sale is required by FTC regulations; this can be done in a number of ways. The text of the warranty can be attached to the product or placed in close conjunction to it. It can be maintained in a binder kept in each department or otherwise easily accessible to the consumer. Either the binders must be in plain sight or signs must be posted to call the prospective buyer’s attention to them. A notice containing the text of the warranty can be posted, or the warranty itself can be printed on the product’s package or container.

Phantom warranties are addressed by the Magnuson-Moss Act. As we have seen, the UCC permits the seller to disclaim implied warranties. This authority often led sellers to give what were called phantom warranties—that is, the express warranty contained disclaimers of implied warranties, thus leaving the consumer with fewer rights than if no express warranty had been given at all. In the words of the legislative report of the act, “The bold print giveth, and the fine print taketh away.” The act abolished these phantom warranties by providing that if the seller gives a written warranty, whether express or implied, he cannot disclaim or modify implied warranties. However, a seller who gives a limited warranty can limit implied warranties to the duration of the limited warranty, if the duration is reasonable.

A seller’s ability to disclaim implied warranties is also limited by state law in two ways. First, by amendment to the UCC or by separate legislation, some states prohibit disclaimers whenever consumer products are sold. A number of states have special laws that limit the use of the UCC implied warranty disclaimer rules in consumer sales. Some of these appear in amendments to the UCC and others are in separate statutes. The broadest approach is that of the nine states that prohibit the disclaimer of implied warranties in consumer sales (Massachusetts, Connecticut, Maine, Vermont, Maryland, the District of Columbia, West Virginia, Kansas, Mississippi, and, with respect to personal injuries only, Alabama). There is a difference in these states whether the rules apply to manufacturers as well as retailers. Second, the UCC at 2-302 provides that unconscionable contracts or clauses will not be enforced. UCC 2-719(3) provides that limitation of damages for personal injury in the sale of “consumer goods is prima facie unconscionable, but limitation of damages where the loss is commercial is not.”

A first problem with warranty theory, then, is that it’s possible to disclaim or limit the warranty. The worst abuses of manipulative and tricky warranties are eliminated by the Magnuson-Moss Act, but there are several other reasons that warranty theory is not the panacea for claimants who have suffered damages or injuries as a result of defective products.[16]

Key Takeaway

A first basis of recovery in products-liability theory is breach of warranty. There are two types of warranties: express and implied. Under the implied category are three major subtypes: the implied warranty of merchantability (only given by merchants), the implied warranty of fitness for a particular purpose, and the implied warranty of title. There are a number of problems with the use of warranty theory: there must have been a sale of the goods; the plaintiff must bring the action within the statute of limitations; and the plaintiff must notify the seller within a reasonable time. The seller may—within the constraints of the Magnuson-Moss Act—limit or exclude express warranties or limit or exclude implied warranties.

10.3 Strict Liability in Tort

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to do the following:

- Recognize how the tort theory of negligence may be of use in products-liability suits.

- Understand why negligence is often not a satisfactory cause of action in such suits: proof of it may be difficult, and there are powerful defenses to claims of negligence.

- Know what “strict products liability” means and how it differs from the other two products-liability theories.

- Understand the basic requirements to prove strict products liability.

- See what obstacles to recovery remain with this doctrine.

In addition to contract-law based theories for product liability, tort theories offer powerful remedies for product liability. Consumers may allege negligence, or proceed on a strict products liability theory.

10.3.1 Negligence Claims for Products Liability

Negligence is the second theory raised in the typical products-liability case. It is a tort theory (as compared to breach of warranty, which is of course a contract theory), and it does have this advantage over warranty theory: privity (a contractual relationship) is never relevant. A pedestrian is struck in an intersection by a car whose brakes were defectively manufactured. Under no circumstances would breach of warranty be a useful cause of action for the pedestrian—there is no privity at all.

There are substantial difficulties in using negligence as a cause of action in products liability cases. These include:

- Proving negligence at all: just because a product is defective does not necessarily prove the manufacturer breached a duty of care.

- Proximate cause: even if there was some negligence, the plaintiff must prove her damages flowed proximately from that negligence.

- Contributory and comparative negligence: the plaintiff’s own actions contributed to the damages.

- Subsequent alteration of the product: generally the manufacturer will not be liable if the product has been changed.

- Misuse or abuse of the product: using a lawn mower to trim a hedge or taking too much of a drug are examples.

- Assumption of the risk: knowingly using the product in a risky way.

Preemption[17] (or “pre-emption”) is another possible defense: suppose there is a federal standard concerning the product, and the defendant manufacturer meets it, but the standard is not really very protective. (It is not uncommon, of course, for federal standard makers of all types to be significantly influenced by lobbyists for the industries being regulated by the standards.) Is it enough for the manufacturer to point to its satisfaction of the standard so that such satisfaction preempts (takes over) any common-law negligence claim? “We built the machine to federal standards: we can’t be liable. Our compliance with the federal safety standard is an affirmative defense.”

Preemption[17] (or “pre-emption”) is another possible defense: suppose there is a federal standard concerning the product, and the defendant manufacturer meets it, but the standard is not really very protective. (It is not uncommon, of course, for federal standard makers of all types to be significantly influenced by lobbyists for the industries being regulated by the standards.) Is it enough for the manufacturer to point to its satisfaction of the standard so that such satisfaction preempts (takes over) any common-law negligence claim? “We built the machine to federal standards: we can’t be liable. Our compliance with the federal safety standard is an affirmative defense.”

Preemption is typically raised as a defense in suits about (1) cigarettes, (2) FDA-approved medical devices, (3) motor-boat propellers, (4) pesticides, and (5) motor vehicles. This is a complex area of law. Questions inevitably arise as to whether there was federal preemption, express or implied. Sometimes courts find preemption and the consumer loses; sometimes the courts don’t find preemption and the case goes forward. According to one lawyer who works in this field, there has been “increasing pressure on both the regulatory and congressional fronts to preempt state laws.” That is, the usual defendants (manufacturers) push Congress and the regulatory agencies to state explicitly in the law that the federal standards preempt and defeat state law.[18]

10.3.2 Strict Liability

The warranties grounded in the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) are often ineffective in assuring recovery for a plaintiff’s injuries. The notice requirements and the ability of a seller to disclaim the warranties remain bothersome problems, as does the privity requirement in those states that continue to adhere to it.

Negligence as a products-liability theory obviates any privity problems, but negligence comes with a number of familiar defenses and with the problems of preemption.

To overcome the obstacles, judges have gone beyond the commercial statutes and the ancient concepts of negligence. They have fashioned a tort theory of products liability based on the principle of strict products liability. One court expressed the rationale for the development of the concept as follows: “The rule of strict liability for defective products is an example of necessary paternalism judicially shifting risk of loss by application of tort doctrine because [the UCC] scheme fails to adequately cover the situation. Judicial paternalism is to loss shifting what garlic is to a stew—sometimes necessary to give full flavor to statutory law, always distinctly noticeable in its result, overwhelmingly counterproductive if excessive, and never an end in itself.[19] Paternalism or not, strict liability has become a very important legal theory in products-liability cases.

10.3.2.1 Strict Liability Defined The formulation of strict liability that most courts use is Section 402A of the Restatement of Torts (Second), set out here in full:

- One who sells any product in a defective condition unreasonably dangerous to the user or consumer or to his property is subject to liability for physical harm thereby caused to the ultimate user or consumer, or to his property, if

- (a) the seller is engaged in the business of selling such a product, and

- (b) it is expected to and does reach the user or consumer without substantial change in the condition in which it is sold.

- This rule applies even though

- (a) the seller has exercised all possible care in the preparation and sale of his product, and

- (b) the user or consumer has not bought the product from or entered into any contractual relation with the seller.

Section 402A of the Restatement avoids the warranty booby traps. It states a rule of law not governed by the UCC, so limitations and exclusions in warranties will not apply to a suit based on the Restatement theory. And the consumer is under no obligation to give notice to the seller within a reasonable time of any injuries. Privity is not a requirement; the language of the Restatement says it applies to “the user or consumer,” but courts have readily found that bystanders in various situations are entitled to bring actions under Restatement, Section 402A. The formulation of strict liability, though, is limited to physical harm. Many courts have held that a person who suffers economic loss must resort to warranty law.

Strict liability avoids some negligence traps, too. No proof of negligence is required.

10.3.2.2 Section 402A Elements

10.3.2.2.1 Product in a Defective Condition Sales of goods but not sales of services are covered under the Restatement, Section 402A. Furthermore, the plaintiff will not prevail if the product was safe for normal handling and consumption when sold. A glass soda bottle that is properly capped is not in a defective condition merely because it can be broken if the consumer should happen to drop it, making the jagged glass dangerous. Chocolate candy bars are not defective merely because you can become ill by eating too many of them at once. On the other hand, a seller would be liable for a product defectively packaged, so that it could explode or deteriorate and change its chemical composition. A product can also be in a defective condition if there is danger that could come from an anticipated wrongful use, such as a drug that is safe only when taken in limited doses. Under those circumstances, failure to place an adequate dosage warning on the container makes the product defective.

The plaintiff bears the burden of proving that the product is in a defective condition, and this burden can be difficult to meet. Many products are the result of complex feats of engineering. Expert witnesses are necessary to prove that the products were defectively manufactured, and these are not always easy to come by. This difficulty of proof is one reason why many cases raise the failure to warn as the dispositive issue, since in the right case that issue is far easier to prove. The Anderson case (detailed in the exercises at the end of this chapter) demonstrates that the plaintiff cannot prevail under strict liability merely because he was injured. It is not the fact of injury that is dispositive but the defective condition of the product.

10.3.2.2.2 Unreasonably Dangerous The product must be not merely dangerous but unreasonably dangerous. Most products have characteristics that make them dangerous in certain circumstances. As the Restatement commentators note, “Good whiskey is not unreasonably dangerous merely because it will make some people drunk, and is especially dangerous to alcoholics; but bad whiskey, containing a dangerous amount of fuel oil, is unreasonably dangerous. Good butter is not unreasonably dangerous merely because, if such be the case, it deposits cholesterol in the arteries and leads to heart attacks; but bad butter, contaminated with poisonous fish oil, is unreasonably dangerous.”[20] Under Section 402A, “the article sold must be dangerous to an extent beyond that which would be contemplated by the ordinary consumer who purchases it, with the ordinary knowledge common to the community as to its characteristics.”

Even high risks of danger are not necessarily unreasonable. Some products are unavoidably unsafe; rabies vaccines, for example, can cause dreadful side effects. But the disease itself, almost always fatal, is worse. A product is unavoidably unsafe when it cannot be made safe for its intended purpose given the present state of human knowledge. Because important benefits may flow from the product’s use, its producer or seller ought not to be held liable for its danger.

However, the failure to warn a potential user of possible hazards can make a product defective under Restatement, Section 402A, whether unreasonably dangerous or even unavoidably unsafe. The dairy farmer need not warn those with common allergies to eggs, because it will be presumed that the person with an allergic reaction to common foodstuffs will be aware of them. But when the product contains an ingredient that could cause toxic effects in a substantial number of people and its danger is not widely known (or if known, is not an ingredient that would commonly be supposed to be in the product), the lack of a warning could make the product unreasonably dangerous within the meaning of Restatement, Section 402A. Many of the suits brought by asbestos workers charged exactly this point; “The utility of an insulation product containing asbestos may outweigh the known or foreseeable risk to the insulation workers and thus justify its marketing. The product could still be unreasonably dangerous, however, if unaccompanied by adequate warnings. An insulation worker, no less than any other product user, has a right to decide whether to expose himself to the risk.”[21] This rule of law came to haunt the Manville Corporation: it was so burdened with lawsuits, brought and likely to be brought for its sale of asbestos—a known carcinogen—that it declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 1982 and shucked its liability.[22]

10.3.2.2.3 Engaged in the Business of Selling Restatement, Section 402A(1)(a), limits liability to sellers “engaged in the business of selling such a product.” The rule is intended to apply to people and entities engaged in business, not to casual one-time sellers. The business need not be solely in the defective product; a movie theater that sells popcorn with a razor blade inside is no less liable than a grocery store that does so. But strict liability under this rule does not attach to a private individual who sells his own automobile. In this sense, Restatement, Section 402A, is analogous to the UCC’s limitation of the warranty of merchantability to the merchant.

The requirement that the defendant be in the business of selling gets to the rationale for the whole concept of strict products liability: businesses should shoulder the cost of injuries because they are in the best position to spread the risk and distribute the expense among the public. This same policy has been the rationale for holding bailors and lessors liable for defective equipment just as if they had been sellers.[23]

10.3.2.2.4 Reaches the User without Change in Condition Restatement, Section 402A(1)(b), limits strict liability to those defective products that are expected to and do reach the user or consumer without substantial change in the condition in which the products are sold. A product that is safe when delivered cannot subject the seller to liability if it is subsequently mishandled or changed. The seller, however, must anticipate in appropriate cases that the product will be stored; faulty packaging or sterilization may be the grounds for liability if the product deteriorates before being used.

10.3.2.2.5 Liability Despite Exercise of All Due Care Strict liability applies under the Restatement rule even though “the seller has exercised all possible care in the preparation and sale of his product.” This is the crux of “strict liability” and distinguishes it from the conventional theory of negligence. It does not matter how reasonably the seller acted or how exemplary is a manufacturer’s quality control system—what matters is whether the product was defective and the user injured as a result. Suppose an automated bottle factory manufactures 1,000 bottles per hour under exacting standards, with a rigorous and costly quality-control program designed to weed out any bottles showing even an infinitesimal amount of stress. The plant is “state of the art,” and its computerized quality-control operation is the best in the world. It regularly detects the one out of every 10,000 bottles that analysis has shown will be defective. Despite this intense effort, it proves impossible to weed out every defective bottle; one out of one million, say, will still escape detection. Assume that a bottle, filled with soda, finds its way into a consumer’s home, explodes when handled, sends glass shards into his eye, and blinds him. Under negligence, the bottler has no liability; under strict liability, the bottler will be liable to the consumer.

10.3.2.2.6 Liability without Contractual Relation Under Restatement, Section 402A(2)(b), strict liability applies even though the user has not purchased the product from the seller nor has the user entered into any contractual relation with the seller. In short, privity is abolished and the injured user may use the theory of strict liability against manufacturers and wholesalers as well as retailers. Here, however, the courts have varied in their approaches; the trend has been to allow bystanders recovery. The Restatement explicitly leaves open the question of the bystander’s right to recover under strict liability.

10.3.2.3 Specific Strict Liability Theories Plaintiffs in strict products liability actions apply these standards through three theories: manufacturing defect, design defect, and failure to warn (which is really just a special case of design defect, with the defect being the failure to warn).

10.3.2.3.1 Manufacturing Defect A manufacturing defect claim centers on the production process. The plaintiff alleges the product, although potentially designed correctly, was produced in a faulty manner. This error in the production process resulted in the plaintiff’s injury.

10.3.2.3.2 Design Defect Manufacturers can be, and often are, held liable for injuries caused by products that were defectively designed. The question is whether the designer used reasonable care in designing a product reasonably safe for its foreseeable use. The concern over reasonableness and standards of care are elements of negligence theory.

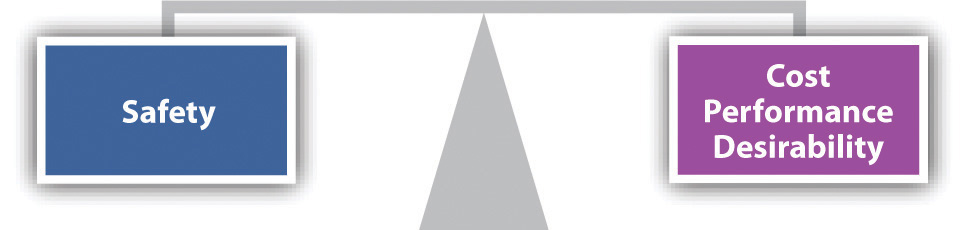

Defective-design cases can pose severe problems for manufacturing and safety engineers. More safety means more cost. Designs altered to improve safety may impair functionality and make the product less desirable to consumers. At what point safety comes into reasonable balance with performance, cost, and desirability is impossible to forecast accurately, though some factors can be taken into account. For example, if other manufacturers are marketing comparable products whose design are intrinsically safer, the less-safe products are likely to lose a test of reasonableness in court.

10.3.2.3.3 Failure to Warn We noted that a product may be defective if the manufacturer failed to warn the user of potential dangers. Whether a warning should have been affixed is often a question of what is reasonably foreseeable, and the failure to affix a warning will be treated as negligence. The manufacturer of a weed killer with poisonous ingredients is certainly acting negligently when it fails to warn the consumer that the contents are potentially lethal.

The law governing the necessity to warn and the adequacy of warnings is complex. What is reasonable turns on the degree to which a product is likely to be misused and, as the disturbing Laaperi case (below) illustrates, whether the hazard is obvious.

10.3.3 Problems with Strict Liability

Strict liability is liability without proof of negligence and without privity. It would seem that strict liability is the “holy grail” of products-liability lawyers: the complete answer. Well, no, it’s not the holy grail. It is certainly true that 402A abolishes the contractual problems of warranty. Restatement, Section 402A, Comment m, says,

The rule stated in this Section is not governed by the provisions of the Uniform Commercial Code, as to warranties; and it is not affected by limitations on the scope and content of warranties, or by limitation to “buyer” and “seller” in those statutes. Nor is the consumer required to give notice to the seller of his injury within a reasonable time after it occurs, as provided by the Uniform Act. The consumer’s cause of action does not depend upon the validity of his contract with the person from whom he acquires the product, and it is not affected by any disclaimer or other agreement, whether it be between the seller and his immediate buyer, or attached to and accompanying the product into the consumer’s hands. In short, “warranty” must be given a new and different meaning if it is used in connection with this Section. It is much simpler to regard the liability here stated as merely one of strict liability in tort.

Inherent in the Restatement’s language is the obvious point that if the product has been altered, losses caused by injury are not the manufacturer’s liability. Beyond that there are still some limitations to strict liability.

10.3.3.1 Disclaimers Comment m specifically says the cause of action under Restatement, Section 402A, is not affected by disclaimer. But in nonconsumer cases, courts have allowed clear and specific disclaimers. In 1969, the Ninth Circuit observed: “In Kaiser Steel Corp. the [California Supreme Court] court upheld the dismissal of a strict liability action when the parties, dealing from positions of relatively equal economic strength, contracted in a commercial setting to limit the defendant’s liability. The court went on to hold that in this situation the strict liability cause of action does not apply at all. In reaching this conclusion, the court in Kaiser reasoned that strict liability ‘is designed to encompass situations in which the principles of sales warranties serve their purpose “fitfully at best.” ’ ” It concluded that in such commercial settings the UCC principles work well and “to apply the tort doctrines of products liability will displace the statutory law rather than bring out its full flavor.”[24]

10.3.3.2 Plaintiff’s Conduct Conduct by the plaintiff herself may defeat recovery in two circumstances.

10.3.3.2.1 Assumption of Risk Courts have allowed the defense of assumption of the risk in strict products-liability cases. A plaintiff assumes the risk of injury, thus establishing defense to claim of strict products liability, when he is aware the product is defective, knows the defect makes the product unreasonably dangerous, has reasonable opportunity to elect whether to expose himself to the danger, and nevertheless proceeds to make use of the product. The rule makes sense.

10.3.3.2.2 Misuse or Abuse of the Product Where the plaintiff does not know a use of the product is dangerous but nevertheless uses for an incorrect purpose, a defense arises, but only if such misuse was not foreseeable. If it was, the manufacturer should warn against that misuse. In Eastman v. Stanley Works, a carpenter used a framing hammer to drive masonry nails; the claw of the hammer broke off, striking him in the eye.[25] He sued. The court held that while a defense does exist “where the product is used in a capacity which is unforeseeable by the manufacturer and completely incompatible with the product’s design. . . misuse of a product suggests a use which was unanticipated or unexpected by the product manufacturer, or unforeseeable and unanticipated [but] it was not the case that reasonable minds could only conclude that appellee misused the [hammer]. Though the plaintiff’s use of the hammer might have been unreasonable, unreasonable use is not a defense to a strict product-liability action or to a negligence action.”

10.3.3.3 Limited Remedy The Restatement says recovery under strict liability is limited to “physical harm thereby caused to the ultimate user or consumer, or to his property,” but not other losses and not economic losses. In Atlas Air v. General Electric, a New York court held that the “economic loss rule” (no recovery for economic losses) barred strict products-liability and negligence claims by the purchaser of a used airplane against the airplane engine manufacturer for damage to the plane caused by an emergency landing necessitated by engine failure, where the purchaser merely alleged economic losses with respect to the plane itself, and not damages for personal injury (recovery for damage to the engine was allowed).[26]

But there are exceptions. In Duffin v. Idaho Crop Imp. Ass’n, the court recognized that a party generally owes no duty to exercise due care to avoid purely economic loss, but if there is a “special relationship” between the parties such that it would be equitable to impose such a duty, the duty will be imposed.[27] “In other words, there is an extremely limited group of cases where the law of negligence extends its protections to a party’s economic interest.”

Key Takeaway

Negligence is a second possible cause of action for products-liability claimants. A main advantage is that no issues of privity are relevant, but there are often problems of proof; there are a number of robust common-law defenses, and federal preemption is a recurring concern for plaintiffs’ lawyers.

Because the doctrines of breach of warranty and negligence did not provide adequate relief to those suffering damages or injuries in products-liability cases, beginning in the 1960s courts developed a new tort theory: strict products liability, restated in the Second Restatement, section 402A. Basically the doctrine says that if goods sold are unreasonably dangerous or defective, the merchant-seller will be liable for the immediate property loss and personal injuries caused thereby. But there remain obstacles to recovery even under this expanded concept of liability: disclaimers of liability have not completely been dismissed, the plaintiff’s conduct or changes to the goods may limit recovery, and—with some exceptions—the remedies available are limited to personal injury (and damage to the goods themselves); economic loss is not recoverable.

10.4 Tort Reform

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to do the following:

- See why tort reform is advocated, why it is opposed, and what interests take each side.

- Understand some of the significant state reforms in the last two decades.

- Know what federal reforms have been instituted.

10.4.1 The Cry for Reform

In 1988, The Conference Board published a study that resulted from a survey of more than 500 chief executive officers from large and small companies regarding the effects of products liability on their firms. The study concluded that US companies are less competitive in international business because of these effects and that products-liability laws must be reformed. The reform effort has been under way ever since, with varying degrees of alarms and finger-pointing as to who is to blame for the “tort crisis,” if there even is one. Business and professional groups beat the drums for tort reform as a means to guarantee “fairness” in the courts as well as spur US economic competitiveness in a global marketplace, while plaintiffs’ attorneys and consumer advocates claim that businesses simply want to externalize costs by denying recovery to victims of greed and carelessness.

Each side vilifies the other in very unseemly language: probusiness advocates call consumer- oriented states “judicial h***-holes” and complain of “well-orchestrated campaign[s] by tort lawyer lobbyists and allies to undo years of tort reform at the state level,”[28] while pro-plaintiff interests claim that there is “scant evidence” of any tort abuse.[29] It would be more amusing if it were not so shrill and partisan. Perhaps the most one can say with any certainty is that peoples’ perception of reality is highly colored by their self-interest. In any event, there have been reforms (or, as the detractors say, “deforms”).

Prodded by astute lobbying by manufacturing and other business trade associations, state legislatures responded to the cries of manufacturers about the hardships that the judicial transformation of the products-liability lawsuit ostensibly worked on them. Most state legislatures have enacted at least one of some three dozen “reform” proposal pressed on them over the last two decades. Some of these measures do little more than affirm and clarify case law. Among the most that have passed in several states are outlined in the next sections.

10.4.1.1 Statutes of Repose Perhaps nothing so frightens the manufacturer as the occa- sional reports of cases involving products that were fifty or sixty years old or more at the time they injured the plaintiff. Many states have addressed this problem by enacting the so-called statute of repose.[30] This statute establishes a time period, generally ranging from six to twelve years; the manufacturer is not liable for injuries caused by the product after this time has passed.

10.4.1.2 State-of-the-Art Defense Several states have enacted laws that prevent advances in technology from being held against the manufacturer. The fear is that a plaintiff will convince a jury a product was defective because it did not use technology that was later available. Manufacturers have often failed to adopt new advances in technology for fear that the change will be held against them in a products-liability suit. These new statutes declare that a manufacturer has a valid defense if it would have been technologically impossible to have used the new and safer technology at the time the product was manufactured.

Key Takeaway

Business advocates claim the American tort system—products-liability law included—is broken and corrupted by grasping plaintiffs’ lawyers; plaintiffs’ lawyers say businesses are greedy and careless and need to be smacked into recognition of its responsibilities to be more careful. The debate rages on, decade after decade, but there have been some reforms at the state level.

- Upton Sinclair, The Jungle (New York: Signet Classic, 1963), 136. ↵

- For example, google “open class action lawsuit settlements” to see what’s currently being litigated. ↵

- Michael Orey, “Taking on Toy Safety,” BusinessWeek, March 6, 2009. ↵

- A guarantee. ↵

- The legal theory imposing liability on a person for the proximate consequences of her carelessness. ↵

- Liability imposed on a merchant-seller of defective goods without fault. ↵

- Any manifestation of the nature or quality of goods that becomes a basis of the bargain. ↵

- Rhodes Pharmacal Co. v. Continental Can Co., 219 N.E.2d 726 (Ill. 1976). ↵

- Wat Henry Pontiac Co. v. Bradley, 210 P.2d 348 (Okla. 1949). ↵

- Frederickson v. Hackney, 198 N.W. 806 (Minn. 1924). ↵

- A warranty imposed by law that comes along with a product automatically. ↵

- A seller’s implied warranty that the goods will be suitable for the buyer’s expressed need. ↵

- Menzel v. List, 246 N.E.2d 742 (N.Y. 1969). ↵

- Under the Magnuson-Moss Act, a complete promise of satisfaction limited only in duration. ↵

- Under the Magnuson-Moss Act, a less-than-full warranty. ↵

- Other issues with warranty law that may limit the plaintiff’s recovery are lack of “privity” (a contractual relationship with the seller), along with tort-theories like assumption of the risk. ↵

- The theory that a federal law supersedes any inconsistent state law or regulation. ↵

- C. Richard Newsome and Andrew F. Knopf, “Federal Preemption: Products Lawyers Beware,” Florida Justice Association Journal, July 27, 2007. ↵

- Kaiser Steel Corp. v. Westinghouse Electric Corp., 127 Cal. Rptr. 838 (Cal. 1976). ↵

- Restatement (Second) of Contracts, Section 402A(i). ↵

- Borel v. Fibreboard Paper Products Corp., 493 F.Zd 1076 (5th Cir. 1973). ↵

- In re Johns-Manville Corp., 36 R.R. 727 (So. Dist. N.Y. 1984). ↵

- Martin v. Ryder Rental, Inc., 353 A.2d 581 (Del. 1976). ↵

- Idaho Power Co. v. Westinghouse Electric Corp., 596 F.2d 924, 9CA (1979). ↵

- Eastman v. Stanley Works, 907 N.E.2d 768 (Ohio App. 2009). ↵

- Atlas Air v. General Electric, 16 A.D.3d 444 (N.Y.A.D. 2005). ↵

- Duffin v. Idaho Crop Imp. Ass’n, 895 P.2d 1195 (Idaho 1995). ↵

- American Tort Reform Association website, accessed March 1, 2011, http://www.atra.org. ↵

- http://www.shragerlaw.com/html/legal_rights.html. ↵

- A statute limiting the time that a product manufacturer can be liable for its defects. ↵