19 Active learning and student engagement

Students learn and retain information and skills better if they are actively involved in the learning process. In Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom, Bonwell and Eison define strategies that facilitate active learning as “instructional activities involving students in doing things and thinking about what they are doing” (Bonwell & Eison, 1991, p. 2). Lombardi and Shipley define it as a “classroom situation in which the instructor and instructional activities explicitly afford students agency for their learning” (Lombardi & Shipley, 2021, p. 15).

Active learning involves students developing discipline-based skills and higher-order thinking skills, such as analysis, synthesis, and evaluation, rather than instructors simply transmitting information. It also encourages students to explore their attitudes and values. Research has shown that active learning links to higher-order learning outcomes (Connell, Donovan, & Chambers, 2015), increases motivation, promotes inclusion of all students, and decreases course failure (Eddy & Hogan, 2014; Freeman et al., 2007; Freeman et al., 2014; Prince, 2004).

To help you incorporate active learning into your classroom, you can try various classroom assessment techniques (CATs). They are usually non-graded and anonymous in-class activities that provide feedback on teaching and learning processes and increase student engagement. Here are some examples that you can use in your class:

- Minute papers are simple, engaging, and adaptable to various purposes. The goal of this exercise—which can take a minute or two—is to reflect on learning and gather feedback on teaching and the material. Minute papers can help you discover what did or did not work well and provide ideas about how to teach in new ways. They can be used in classes of any size. Here are some examples of questions for this activity: “What are the two most significant things you learned in today’s class?” “What was the most confusing point in today’s reading?” “How useful for your learning was the group activity that we did in class today? Please share some details.”

- Classroom opinion polls, where students reveal the degree of their agreement or disagreement with an idea or a prompt (using Zoom polls or Top Hat, writing on paper, or raising hands). One way of doing this is the human Likert scale, where people line up according to two ends of a scale and then people at the extreme and middle positions argue for their point to see if they can get anyone to change their minds. It also requires students to discuss gradations of a perspective as they line up.

- Concept maps help students indicate connections between a central concept and other concepts they have learned and analyzed.

Active learning techniques are often connected to group work and collaborative learning. Here are some examples of such activities that you can adapt to your teaching context:

- Small group activities encourage more students to speak and actively participate in class. It is harder to be a passive learner in a group of three than in a group of 30. Small group activities can be done even in large lecture courses with hundreds of students. All it takes is about five minutes and a well-thought-out question or task. One easy to implement example of a small group activity is think-pair-share. Instructors pose a question or share a prompt; students first reflect on it for a moment (THINK) then share their thoughts with a person sitting near them (PAIR) or a randomly selected partner. Finally, the small groups communicate (SHARE) their takeaways to the entire class as a large group discussion.

- A gallery walk activity places prompts or products of individual or group work around the room and asks students to walk from station to station to mark, review, comment, or discuss displayed materials (Kagan, 1994).

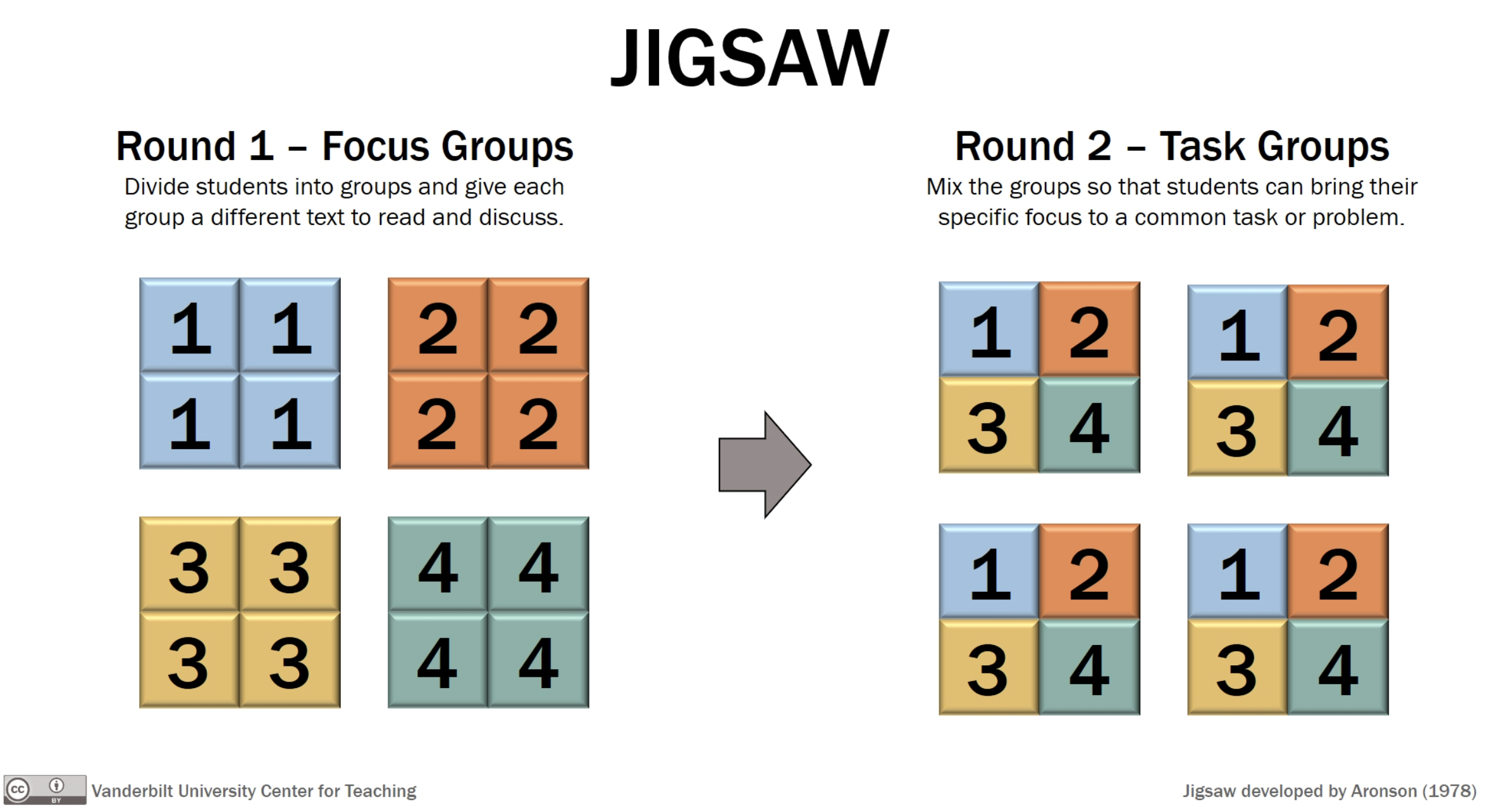

- A jigsaw is a cooperative learning strategy where students work in teams to solve a problem or discuss a text. It helps students examine complex issues, projects, or readings; increases student engagement; increases collaboration; and allows students to share diverse perspectives. The class is divided into several “focus groups” which are assigned separate subtopics relating to a common theme. Group members research the topic, meet to discuss and refine their understanding, then reassemble with members of other focus groups. Experts report their findings to their new group mates, or the group collaboratively solves a task incorporating all the subtopics.

https://cdn.vanderbilt.edu/vu-wp0/wp-content/uploads/sites/59/2020/06/11174426/Jigsaw-Final.jpg

Gallery walk and jigsaw activities are examples of embodied learning. To learn more, see a Center for Teaching resource developed by Iowa undergraduate students.

While active learning is possible in any classroom, Iowa offers a special program called TILE (Transform, Interact, Learn, Engage). TILE classrooms are designed for active learning to accommodate 24 to 81 students. These classrooms are supplied with circular tables, laptops, flat-screen monitors, multiple projectors, and whiteboards or glass boards, making it easy to integrate individual and group activities. The placement of the instructor workstation in the middle of the classroom enhances students’ engagement and invites students to actively participate.

To teach in a TILE classroom, complete the Center for Teaching’s TILE consultation (email us at tile@uiowa.edu), and consult with your department admins to request classroom reservations.

Mitigating student resistance to active learning

Evidence about the positive impact of active learning on academic performance and student engagement is clear, but students may still resist it. To positively influence students’ openness to active learning strategies, consider:

- Explaining course expectations and the purpose and value of an activity (Tharayil et al., 2018).

- Sharing with students that feeling discomfort when starting a new task is normal and previewing the most challenging aspects of the activity (DeMonbrun et al., 2017; Wiggins et al., 2017). You can also explain that effort is not a sign of poor learning but a sign of effective learning.

- Making sure you are available for questions when students are working on an activity. Circulate around the room, make eye contact with students, and nurture their curiosity about what they might do next (DeMonbrun et al., 2017; Wiggins et al., 2017).

- Collecting student feedback about the activity through a minute paper or a poll and addressing it in your next class.

💡 Please reflect:

Given these strategies and ideas, what would be your next step in facilitating and cultivating active learning for your students? What support do you need?

Feedback/Errata