Scaffolding

What is scaffolding?

By scaffolding we mean breaking down complex tasks into smaller components, providing interim structure, and articulating the required steps between them and the larger goals and skills.

Walker and Shaw (2018) define scaffolding as “the provision of sufficient support to promote learning when concepts and skills are being first introduced” (p. 224). Scaffolding is a critical component of UDL as it provides incremental steps aligned with the course goals and aids to make learning accessible while maintaining high achievement standards and rigor (Black et al., 2015).

Scaffolds allow for flexibility and choice in how students access content and demonstrate skills (Schelly et al., 2011) and make learning accessible to a broader range of students by reducing initial complexity and barriers (Rose et al., 2006). For example, a 2017 study demonstrated that scaffolding “can lower the anxiety of students with ASD and play to their strengths of thriving in structured environments” (Austin & Peña, 2017, p. 26). A research article by Walqui (2006) suggests that carefully sequenced and scaffolded instruction enables ESL students to participate more fully in discussion activities.

How does scaffolding work?

Scaffolding techniques align with UDL principles by making learning more accessible while developing and supporting expert, autonomous, and self-regulated learners.

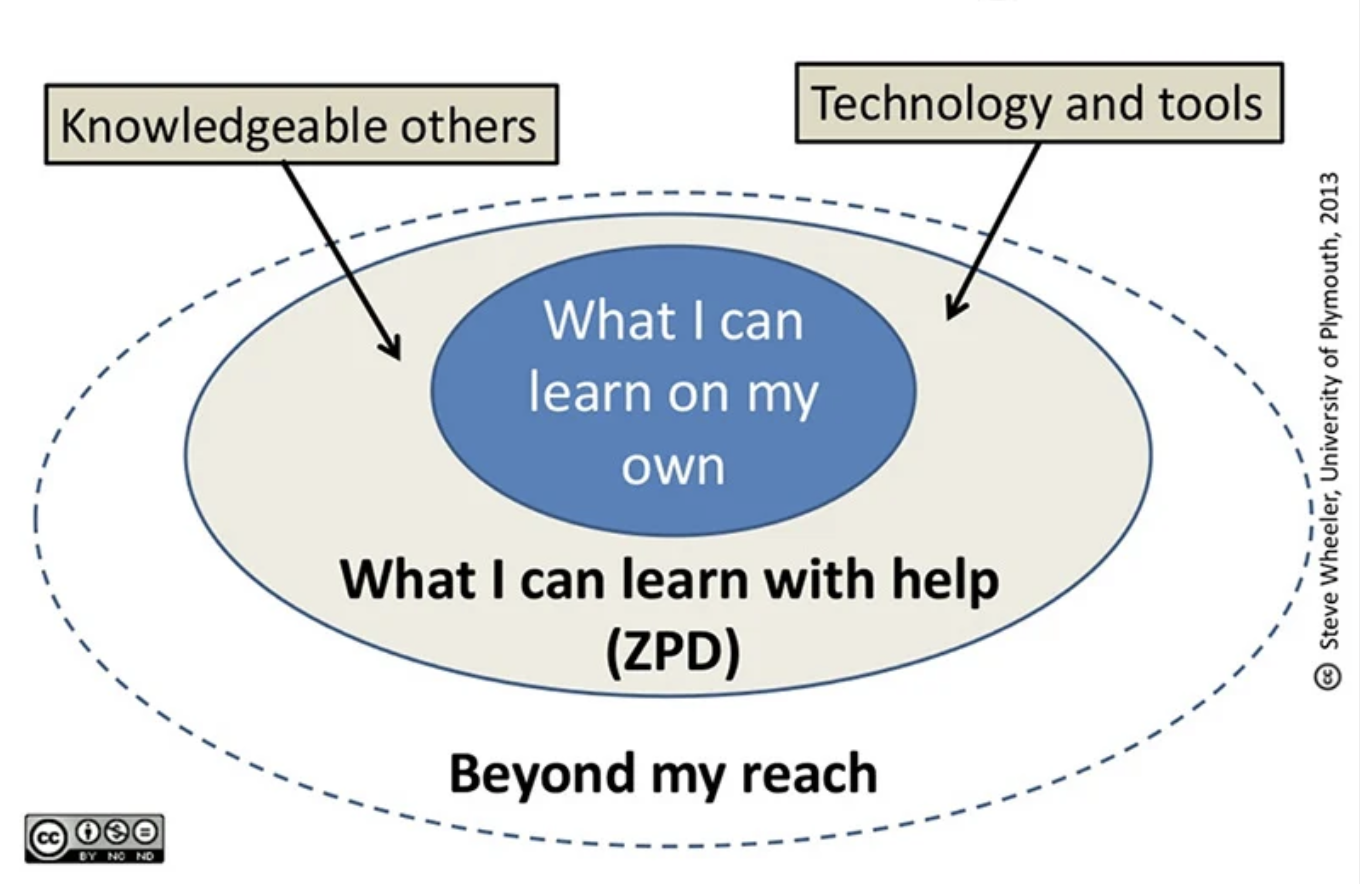

Lev Vygotsky’s term zone of proximal development (ZPD) is an essential concept in scaffolding (1978). The ZPD refers to the gap between what a learner can do independently and what they can achieve with guidance, support of peer learners, more knowledgeable others (TA or professor), technology, and tools (e.g., glossary, graphic organizers).

With scaffolding, the instructor provides just enough assistance to enable the learner to accomplish tasks within their zone of proximal development that they would not have been able to do independently.

Scaffolding enables learners to work within their ZPD by providing the proper amount of assistance needed to successfully accomplish a task slightly beyond their current independent skills or proficiency.

What is an example of scaffolding?

Discussing and analyzing examples of completed assignments.

For instance, in a first-year contracts law course, the professor provides samples of student answers to previous exam hypotheticals to model legal analysis (Guzzetti & Bang, 2011). Students then work in small groups to critique and discuss the model answers before independently attempting their own responses.

What are some ways to scaffold common assignments?

Steps to scaffold a research paper assignment:

- Developing a checklist of what the final paper should include and/or a detailed rubric.

- Giving guidance on evaluating source credibility. As an incremental step, students submit a list of their sources before writing.

- Having students submit drafts of critical sections rather than the whole paper at once.

- Giving feedback on drafts to improve their writing before they compile the entire paper.

Steps to scaffold a classroom discussion:

- Asking students to review and prepare initial responses to discussion prompts or questions provided in advance.

- Incorporating a short pre-writing activity like listing ideas or writing for a couple of minutes on the topic to get their thoughts flowing (e.g., entry ticket, misconception check, warm calling, or write-pair-share).

- Co-developing discussion norms or guidelines, reminding students to listen respectfully, share airtime, and build on each other’s ideas. See sample norms for community guidelines in our Handbook for Teaching Excellence.

- Breaking a large discussion into smaller parts using structured activities like think-pair-share, jigsaw, or 1-2-4-All).

- Assigning student roles (e.g., moderator, presenter) so that students can have focused practice on the the different skills required to participate effectively in a discussion. Roles can be rotated.

- Using scaffolding questions: What evidence supports that idea? How does this relate to [concept X] we studied?

- Debriefing after the discussion to summarize key points and learning, prepare for the next time and develop their overall discussion proficiency. Have students reflect using exit tickets, a one-minute paper, or muddiest point activities.

Think of a major assignment in your course; how could it be scaffolded to remove barriers for learners in your class? Are there ways to design more frequent low-stakes assignments to scaffold major high-stakes assessments? If so, what are some possibilities?

References:

Austin, K., & Peña, E. V. (2017). Exceptional Faculty Members Who Responsively Teach Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders. The Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 30(1), 17–32. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1144609.pdf

Black, R.D., Weinberg, L.A., & Brodwin, M.G. (2015). Universal Design for Learning and Instruction: Perspectives of Students with Disabilities in Higher Education. Exceptionality Education International, 25(2), 1–26.

Guzzetti, B., & Bang, E. (2011). The influence of literacy-based science instruction on adolescents’ interest, participation, and achievement in science. Literacy Research and Instruction, 50(1), 44–67.

Meyer, A., Rose, D.H., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal design for learning: Theory and practice. CAST Professional Publishing.

Rose, D. H., Harbour, W. S., Johnston, C. S., Daley, S. G., & Abarbanell, L. (2006). Universal design for learning in postsecondary education: Reflections on principles and their application. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 19(2), 17.

Schelly, C.L., Davies, P.L., & Spooner, C.L. (2011). Student Perceptions of Faculty Implementation of Universal Design for Learning. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 24(1), 17–30.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Walker, J.D., & Shaw, S. (2018). Scaffolding Strategies for Supporting Effective Universal Design for Learning Implementation. Journal of Special Education Technology, 33(4), 223–235.

Walqui, A. (2006). Scaffolding instruction for English language learners: A conceptual framework. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 9(2), 159-180. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050608668639