2 The Science of Relationships: Power, Privilege, and Oppression

Power, Privilege, and Oppression

Kahlil Gibran’s poem, On Marriage ends with this stanza:

“Give your hearts, but not into each

other’s keeping.

For only the hand of Life can contain

your hearts.

And stand together yet not too near

together:

For the pillars of the temple stand apart,

And the oak tree and the cypress grow

not in each other’s shadow.”

Gibran cleverly compared two lovers to oaks and cypress. Cypress grow deep in the heart of swamps and in wet poorly drained soil, Oaks need well drained soil unless they are water oaks. Cypress trees produce cones and have needles instead of leaves, Oaks have large leaves that tend to drop and then come back every year. These are simplistic and observable differences; these two trees are in some ways similar, but also uniquely different; they have different needs, grow and reproduce in different ways, and bear little resemblance to each other. A clear understanding of this is necessary for each one to thrive if they are planted.

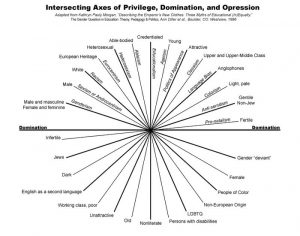

When people decide to form intimate relationships they often focus on the things they have in common and observable traits that they feel are attractive. These include what drew them together, shared experiences, values, and world views. In order to maintain relationships, and to deepen them it is important to also have a clear understanding of our own position in the world, our needs, and our identity. Once we understand our own positionality, then we need to employ what Maxine Greene calls our Social Imagination to understand the position of our partners and how their position in the world has positively and negatively affected aspects of their life.

Going deeper, most of us can easily imagine the ways that we have been marginalized, discriminated against, and oppressed by others. Rarely do we take the opportunity to reflect on how we have had certain privileges that have positioned us to stand on the backs of others to our advantage. This idea first coined in print in 2008 by Norma Akamatsu is termed “Multiplexity,” she attributes this term to Cornel West.

In 1991, Kimberle Crenshaw, a legal scholar wrote a seminal essay called Mapping the Margins: Identity Politics and Violence Against Women of Color. In this essay she asked people to consider the intersection of race and gender as a way to explore intra-group differences. In other words, for Crenshaw being black and being a woman and being from a particular class, having a certain level of education, being non-disabled, etc. all contribute to who she is, being black was not enough to explain how her experiences in the world unfolded. This idea of determining how different categories intersect in a person’s identity was coined by Crenshaw as intersectionality. She initially created this term and applied it to black women’s experiences with violence and patriarchy. Since then scholars have expanded intersectionality to encompass all identities that exist simultaneously in all of us.

Why does this matter in relationships? Within our identities certain categories may shift and move to the forefront depending on the situation. In other words, our identities like our relationships are not static, they are dynamic and ever shifting. This means that within relationships our relational interactions are also dynamic. For example, if one person in a relationship has significant and stagnant notions of gender roles such as, people who identify as women should have long hair or should be passive, and a person with whom they are in a relationship has different ideas, this might create tension and even a conflict. Gender roles are one tiny example. This is true for nearly any category of identity. We have ideas about each category which may or may not match the experiences and identities of others.

This is further complicated by the fact that our identities are on display in different ways and at different times. In a relationship with another person there is some degree of co-construction. Identity theory created first by Sheldon Stryker in the 1960s, and further developed by Peter Burke claims that people have three overlapping elements that form their identity. First is their social identity. This asks them to consider, to which groups do they belong. These groups might be professional, ethnic, social, etc. This is the basic part of intersectionality. Second, what roles are they playing in any given setting. If someone is a teacher in one setting, but a sister in another, and a friend in a third those roles each require different ways of reacting and responding. Finally, there are the traits that we feel identify us. Are we generous, or kind, or creative, etc. These will lead us to enact a set of behaviors that demonstrate our personal traits. These three ideas held in parallel with our intersectional identity create a complex person.

Engaging in a relationship with another person requires that we co-create identities. This means examining what roles we take up in that relationship, what parts of identities are on the margins of society and what parts are the center which is intertwined with power and oppression, what traits we feel are important to enact and perform and what groups we will identify as most important in our lives.

When we also take time to examine our biases, stereotypes, and negative ideas this adds another layer to our relationships. If we are unaware of these it could lead to problems in a relationship. Our identities shape the way we respond to the world, to other people and to the relationships we form.

Definitions:

Intersectionality-coined by Kimberle Crenshaw and expanded by other feminist is used to explain how different parts of identity intersect to explain particular experiences of disadvantage, discrimination, and power.

Privilege-a right, benefit or advantage given because of a favored status or category

Oppression-power or authority or privilege used in a manner that is unjust against a less powerful or advantaged group

Marginality-not centered within identities that are advantaged socially, politically, economically, culturally, on the margins of society

Multiplexity-the concept that when we consider unique constellations of identities we can see how some of them have created disadvantage and some have helped to gain unfair or unjust advantages.

Feminism-an inclusive theory of political, social, cultural, and economic equality and recognition of all genders and sexualities

Case Example:

Mika is a bi-racial lesbian from Minneapolis. Her mother is Japanese-American and her father is African-American. Her parents have been married for at least 40 years. She is from a large family. She is a practicing Christian, she has a law degree, and she is a huge Dallas Cowboys fan. She makes almost $150,000 per year. She is a quiet person who loves to cook, play fantasy football, garden, and spend time with their cats.

Her partner, Patricia, is white. She is also Unitarian. She is a social worker raised in Maryland by a single mother. She is an only child. She likes to build things, host large parties, knit, and she does lots of work in her community. She is on the board of several non-profits. Her salary is roughly $50,000. She is an extrovert and prefers outings and dinner parties to television. Both women are in their early 30s.

One night, while snuggling in bed they get into an argument. It’s Friday night.

Mika rolls over and sighs, “I’m so frustrated why do volunteer every weekend at the dog park on Saturdays and at Habitat for Humanity on Sunday afternoons? We never see each other!”

Patricia, “I love it, I have to get up at 5 am so I can unlock the fence at the dog park. Let’s go to sleep.”

Mika sighs loudly, “I hate dogs.”

Patricia laughs, “If I had a dog I wouldn’t volunteer at the dog park.”

Mika responds grumpily, “I don’t think we have time to properly care for a dog. If you really wanted a dog you would quit volunteering every weekend and spend more time at home.”

Patricia says, “You’re too introverted. I know you’re tired on the weekends, but watching football in sweatpants and eating chips and dip is not my idea of fun.”

Mika says, “I like staying home, plus it helps us save money for the trip we both want to take to Spain.” After this she smiles.

Patricia says, “Listen, I know we are trying to save money. I hate it that I don’t make as much as you, but I try to contribute equally to our household with chores. You would not be able to be a rockstar lawyer if I didn’t feed you and wash your shirts!”

Mika says, “Fine. But I did fix the toilet last week. I don’t care that I make more money. I do care when you spend it without asking me first. Why did you donate $300.00 to Habitat for Humanity without telling me?”

Patricia says, “Gosh, for a lawyer, you are so stingy. I have a master’s degree and you know that I am never going to be rich working as a Social Worker, but I can sleep at night knowing my job matters. You knew I was a social worker when we got married and that I was never going to change careers. Also, that donation is tax deductible.”

Mika gets very quiet.

Patricia rolls over and then says, “Speaking of taxes, my mother wants to go to Spain with us.”

Mika rolls her eyes.

Patricia says, “You know my mother and I are very close. You can’t understand because your family is so different. I’m her only child. She loves you too. She is getting older, I want her to have fun.”

Mika says, “Just because my parents don’t hug does not mean they don’t love us.”

Patricia then says, “Ok, seriously, they are horrible. I think they hate me because I am white and They didn’t even invite us to your brother’s birthday. It’s because of that church. How can they go to a place that does not accept LGBTQ people? What about their own daughter? I know they say they don’t care that we’re lesbians, but I don’t want their hugs.” This make Mika really angry. She gets out of bed and stomps off to her office and slams the door. The discussion turned fight is over. Patricia feels terrible.

What are Patricia and Mika fighting about?

What parts of their identities that might make the fighting more difficult?

What parts of their identities might cause tensions between them? How can they explore these tensions to make their relationship stronger?

Can you think of a relationship where you had differences with the other person that were unexplored? What were the differences between you and the other person?

How did those differences cause conflict?

Money Matters: How Class and Money Can Influence Interpersonal Relationships

There have been times in everyone’s life when they can feel money burning a hole in their pocket and they are torn between their “wants” and their “needs.” Generally people will repeatedly give in to one or the other. Some people are comfortable spending money, some are comfortable saving their money. In couples, these differences can lead to conflict, especially if people have different views and values about financial health.

In spite of money being one of the top reasons couples argue the reality is that oftentimes people are not actually arguing about money, but about things that are far deeper such as long-term security, identity, autonomy, and values. Money can influence each of these things. These ideas are generally tied to our experiences in childhood. For example, if you or your partner grew up in a home where basic needs such as food, shelter, or clothing were scarce then long-term security may matter a great deal and there will be a desire to save money so there is never a fear of scarcity. Conversely, spending habits might swing in the other direction; in other words, they want to make up for lost time and never feel shame about being impoverished again so they may spend excessive amounts on high quality clothing, or gourmet food, or they might even horde or buy multiple versions or bulk quantities of items so that they won’t “run out.”

Much of what this returns to are values. If both people have an income and are independent, sharing their financial decisions may be difficult to negotiate because they value autonomy and feel that if they earn money, they should have complete control over how it is spent. One way couples can think through this conundrum is to answer the question, “What are our shared goals?” How much do they matter, how much are we willing to invest, what will we sacrifice in order to achieve these goals. One partner may not be able to make a case based on money, but instead on labor in terms of reaching shared goals. This can be difficult if their labor is not valued by their partner. For example, if one partner has taken on larger quantities of domestic labor, for example, the labor of doing all the laundry, childcare, petcare, or cooking all of the food so the other partner can earn a higher income or put more time in at their job.

A person’s socio-economic class can have far reaching and long term consequences on their access to health care, their education, employment, and experience with formal systems such as the criminal justice system. People from a lower socio economic class also have statistically higher rates of divorce and in some instances higher rates of single parenting. People from lower socio economic classes are more likely to live together for longer rather than marry early in their relationship.

According to Addo and Sasser (2010) when it comes to finances most married couples pool their resources. If a partner has been divorced in the past they are less likely to pool resources and may instead opt for a joint account as well as an individual account. Many couples believe they should not marry unless they have accumulated some savings, own a car, and maybe even a home. This is known as the “Marriage Bar” (Eads, and Tach, 2016), attaining these things can be difficult for people who begin life in a lower socioeconomic status. They have a lower chance of gaining access to high quality education, higher education after secondary school, and they are more likely to encounter more life stressors along with finanical discrimination. This in turn means they may wait longer to marry.

How do couples sort out disputes over money?

First, the red flags include having different spending habits, being secretive about finances, one partner spending more repeatedly without acknowledgement or some sort of non monetary exchange, the subject of money can easily cause disagreements.

Points to ponder:

Can you think of a time when you have had a disagreement about money with family, friends, or a partner?

What values do you attach to money besides wealth? What about autonomy? (i.e. If you earn it you can spend it how ever you want.)

What kind of contracts would you want to make with a life partner around spending and saving? For example, would you pool your money or have separate accounts? Would you give your children an allowance or would they be paid per chore?

How do you feel about the “Marriage Bar?” Are there things that you would want in place before you made a lifetime commitment to another person or before you cohabitate?

Financial Challenges Faced by the LGBTQ Community

Dating and Money: How to Talk About Finances in Your Relationship

How to Build Wealth and Stay Out of Debt

Case Example:

Jace and Barb are recent college graduates. They have been dating each other for four years and have decided to finally move in together. Jace is Latino and from Southern California. He was raised by a single mother who was a nurse. He has had a job since he was 14 and was financially independent at 18. He put himself through college by bartending and being a bouncer. Now he is a science teacher. Barb is Latina and from a large family in Puerto Rico. Growing up she lived in a big house with her parents and much of her extended family including an Aunt, Uncle, brother, sister, two cousins, and her grandparents. Her family has a successful family business and has always pooled their resources to help one another. Her parents, aunt, and brother helped to financially to get through college. Her brother still pays for her car payments. She recently got a job in marketing. Jace and Barb make about the same salary.

Jace is eager to purchase a new home and take his dream trip to South Africa, but Barb is concerned about sending her little sister to college and visiting her family. Eventually she wants to move back to Puerto Rico. Jace also feels like they should keep their finances separate, Barb wants to pool them in a joint account. Jace has a large savings account and he is worried that if he pools his resources that Barb will spend what he has worked very hard to save. Barb also has a savings account. She puts money into it every month in order to save for her annual trip to Puerto Rico in April. She likes to go every year for a month to celebrate her mother’s birthday. Jace can’t go in April because he is a teacher and has to work. Barb also saves her vacation time for this trip so after April she does not have any significant vacation time saved until October. Jace was hoping to go to South Africa in the summer when he is out of school. His mother might join him if he can help pay for part of her plane ticket. Jace really wanted to share the experience with Barb and his mother.

What values are in play in this relationship?

What solutions would you propose if you were their financial planner? Why?

Additional Resources:

Addison, S., &Coolhart, D. (2015). Expanding the Therapy Paradigm with Queer Couples: A Relational Intersectional Lens. Family Process (54) 435–453.

Alicia Eads and Laura Tach, (2016) Wealth and Inequality in the Stability of Romantic Relationships, The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, Vol. 2, No. 6,Wealth Inequality: Economic and Social Dimensions (October), pp. 197-224.

Crenshaw, K. (1991) Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review. Vol. 43, No. 6 (Jul., 1991), pp. 1241-1299 (59 pages).

Fenaba R. Addo and Sharon Sassler,(2010) Financial Arrangements and Relationship Quality in Low-Income Couples, Family Relations, Vol. 59, No. 4, pp. 408-423

Moradi, B., Grazanka, P. and Santos, C., (2017) Intersectionality Research in Counseling Psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology. Vol. 64, No. 5, 453–457.

Seedall, R., Holtrop, K. and Ruben Parra-Cardona, J. (2014).Diversity, Social Justice, and Intersectionality: A Content Analysis of Three Family Therapy Journals, 2004-2011. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, Vol. 40, No. 2, 139–151.

https://www.law.columbia.edu/pt-br/news/2017/06/kimberle-crenshaw-intersectionality