4 Family of Origin Relationships: Gender, Sexual Orientation, Class

Gender:

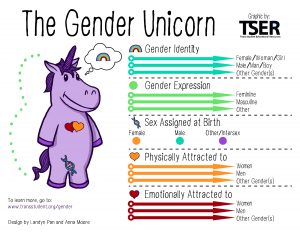

Gender identity is a deep knowledge of self, contextualized by societal norms and available language. Our gender identity can match our biological sex, which we are assigned at birth (cisgender), or can be different from our biological sex (transgender). Gender identity might be male/man, female/woman, neither (agender) or a blend of multiple genders (gender non-binary or gender non-conforming) (Figure 2). Our deep seeded knowledge of self, which informs gender identity, is often developed by early childhood (Martin & Ruble, 2010; Children and Gender Identity, n.d.). Contextualization of gender identity means that our knowledge of self may or may not align with existing gender norms or language available in our society, but context can change. Communities can work to widen their perspectives on gender, and society can work to deconstruct gender norms and create new language that more holistically describe the human experience.

Gender fluidity is the idea that a person may not adhere to a single gender identity. This does not mean that they are, in fact, unknowing or confused about who they are, but rather that their knowledge of self does not fit a single gender. Gender identity terminology continues to grow, encompassing a larger bank of language that can be used to more accurately describe who a person is, however it is important that we recognize the ways in which language can be limiting.

Gender expression is also of important consideration; this is how we display our gender by way of how we dress, groom, or use body language. We must take a moment to recognize that gender is often expressed by the use clothing, make-up, or other grooming habits in a gendered way; this can be perceived as overly stereotypical, and you’re not wrong. Society has normative perceptions of femininity and masculinity and normative beliefs when someone is displaying either of these characteristics (not to mention that blending feminine and masculine or avoiding the expression of either are also possible). However, we also know that gender norms can change over time. Consider the gender box activity listed below in the Family-of-Origin Unit Activities to break down some of our implicit ideas about gender.

When we consider gender and families in present American society, we can identify many points for consideration. Gender has traditionally informed the roles that members of a family play; this can be seen across cultural norms and over generations. Roles and responsibilities have evolved over time, but we continue to see expectations around behaviors including contribution to the family unit, on the basis of need and, at times underlying normative beliefs about sex or gender that are oppressive.

Unfortunately, gender identity, especially when it is not conforming to the binary (man or woman) can be a major point of conflict, distrust, and familial breakdown in situations where FoO are not supportive of a family member’s gender identity. Studies of Trans youth wellbeing show that mental health and rates of self-harm are highly impacted by familial rejection or support (Klein & Sarit, 2016). When families are supportive social networks, this uplifts mental health, decreases instances of self-harm, and contributes to young Trans people receiving the additional resources they need (including healthcare and education amongst others); this has implications for wellbeing and autonomy in the future (Olson, Durwood, DeMeules & McLaughlin 2016; Ryan, Russel, Huebner & Sanchez, 2010). Again, families do not exist in a vacuum, and in a society that continues to display transphobia and other prejudicial discrimination against gender non-conforming individuals, networks of support such as families can serve as a protective factor (Ryan, Russel, Huebner & Sanchez, 2010).

Points to Ponder:

- Is gender identity something I have thought about in relation to my FoO? If not/if so, why?

- What are some societal norms that would contribute to gender identity being a point of conflict for some families?

- How can we support families to support family members with diverse gender identities?

- How are families strengthened by understanding and accepting gender identities? And society?

- Does gender play a role when it comes to expectations or responsibilities in my FoO?

- How have gender roles within families changed or remained the same over time within American society?

Sexual Orientation

Sexual orientation is often grouped with gender identity (described above), without consideration for the fact that these are very different experiences. While gender is about who someone knows that they are, sexual orientation is about attraction to others. Attraction can be physical or emotional (Figure 2) and can be gender specific (only attracted to one gender, heterosexual or homosexual) or gender non-specific (attracted to multiple genders, bisexual or pansexual). Asexuality is also a sexuality, and while for some this truly does mean an absence of sexual attraction altogether, this is not the only definition of asexuality. Asexual individuals may also find that they might exclusively have emotional attraction or exclusively have physical attraction to a partner. This is one example of sexual fluidity. Figure 2, again, shows spectrums of attraction, meaning that every experience is different. No two heterosexual individuals will experience their heterosexuality the same or define it with the same boundaries; this holds true for all other sexual orientation identities.

Our attraction to a specific partner based on our sexual orientation contributes to diverse family formation (Goldberg & Sweeney, 2019). Similarly, to gender identity, however, sexual orientation that deviates from heterosexuality (the American societal norm) can be a point of contention amongst FoO. As with gender minorities, we are understanding more and more about the incredible impact that familial support has on short- and long-term wellbeing of individuals that identify as homosexual or other lesser accepted sexualities (Ryan, Huebner, Diaz & Sanchez, 2009). Encouraging societal changes which are more inclusive to gender and sexual minorities has major implications for the equitable existence of all peoples, and the stability of families.

Points to Ponder:

- Is sexual orientation something that I have thought about in relation to my FoO? If not/if so, why?

- What are societal, cultural, or other norms/practices that influence conflict around sexual orientation in families?

- How can we support families to support family members with diverse sexual orientations?

- How are families strengthened by understanding and accepting sexual orientations? And society?

Class

Class is yet another complex social dimension that is made up of combined perceptions of socioeconomic characteristics and personal characteristics. In their article for Gallup, “What Determines How Americans Perceive Their Social Class,” Bird & Newport (2017) highlight the difference between “objective class” which encompasses income, wealth, education and occupation, and “subjective class” which is how people categorize themselves in class structures. The latter is a compilation of many variables, which may include only some of the objective measures. Class does not exist in isolation, and while we do often think of class as a measure of economic prosperity, it is also associated with race- and gender-based inequities which existed long before the idea of economic class alone.

For families, class as a term may have less functional meaning. However, the effect of class disparities may produce familial stress as the result of unequal or sparse economic resources to accomplish daily needs, and/or to advance family development through traditional institutions (schools, private activities and organizations like clubs, healthcare systems, nutritional systems, etc; Lareau et al., 2007). Emerging work from Dr. Rashmita Mistry, a Developmental Psychologist at UCLA, is uncovering that children are aware of social class much earlier than adults might think (brief local news story included under Want to Know More?). However, it is important to acknowledge the stigmatizing attitudes that accompany class and shape into classism—the prejudicial treatment of individuals on the basis of their social class. The report from the National Council on Family Relations (2007) also points to lesser discussed elements experienced by individuals of “lower class” groups, such as closer relationships with extended family and reliance on community for growth instead of traditional or commercialized activities that “middle class” families have access to. While the disparity of financial access to these activities is clear, it is still of importance to highlight a narrative beyond despair, which humanizes the experience of many people across classes.

Class and poverty walk hand-in-hand, let us turn our attention to experiences of impoverished families as described by Mia Birdsong. As she describes the ingenuity of her acquaintances and friends she also suggests how changing the narrative around class and poverty can help us acknowledge whole human experiences.

Watch the video here.

Points to Ponder:

- What dimensions of class have I experienced in my own FoO?

- When did I become aware of these dimensions or experiences?

- Is there utility in social or economic class?

- What could be positive?

- What could be detrimental?

- What are other social or structural constructs that contribute to how we view class in the United States?

- Do you believe there is stigma associated with class in the United States? If not, why? If so, what are examples?

- Does this impact families?

- What can we do to address class inequities that create disparities for families (in health, wellbeing, family stability, meeting needs, etc.)?

Want to know more?

Carlson, M. J., & England, P. (2011). Studies in Social Inequality: Social Class and Changing Families in an Unequal America. Stanford University Press.

Doussa, H. V., Power, J., & Riggs, D. W. (2017). Family matters: transgender and gender diverse peoples’ experience with family when they transition. Journal of Family Studies, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/13229400.2017.1375965

Laird, J. (1996). Invisible ties: Lesbians and their families of origin. In J. Laird & R.-J. Green (Eds.), Lesbians and gays in couples and families: A handbook for therapists (p. 89–122). Jossey-Bass.

Malpas J., Glaeser E. (2017) Transgender Couples and Families. In: Lebow J., Chambers A., Breunlin D. (eds) Encyclopedia of Couple and Family Therapy. Springer, Cham

Reczek, C. (2020). Sexual‐ and Gender‐Minority Families: A 2010 to 2020 Decade in Review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 300–325. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12607

Riggle, E. D. B., Drabble, L., Veldhuis, C. B., Wootton, A., & Hughes, T. L. (2017). The Impact of Marriage Equality on Sexual Minority Women’s Relationships With Their Families of Origin. Journal of Homosexuality, 65(9), 1190–1206. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2017.1407611

TEDx Talks and Other Videos

Best Life: Kids recognize social class early in life

https://www.wmcactionnews5.com/2020/01/01/best-life-kids-recognize-social-class-early-life/

Family-of-Origin Unit Activities:

- Individual activity: Create a FoO genogram for a particular element of your family—use one of the content areas discussed in this chapter to guide this genogram.

- Full class activity: Gender box activity to break down gender norms and/or masculine and feminine expectations.

- Directions:

- Draw two boxes on the board, label with masculine/feminine

- Breakdown what norms or stereotypes are and give disclaimer that anything that is shared is not assumed to be the personal beliefs of any individual.

- Directions:

- Ask the class to share norms or stereotypes about each group

- After filling the boxes with norms, ask students to assign stereotypical expectations to these—ask them to draw connections to relationships in families and romantic partnerships.

- Break these norms down through reflective discussion. Literally break norms down by erasing them.

References

Bamshad, M., Wooding, S., Salisbury, B. A., & Stephens, J. C. (2004). Deconstructing the relationship between genetics and race. Nature Reviews Genetics, 5(8), 598–609. doi: 10.1038/nrg1401

Children and gender identity: Supporting your child. (2017, September 1). Retrieved February 12, 2020, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/childrens-health/in-depth/children-and-gender-identity/art-20266811

Dollahite, D. C., Marks, L. D., & Dalton, H. (2018). Why Religion Helps and Harms Families: A Conceptual Model of a System of Dualities at the Nexus of Faith and Family Life. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 10(1), 219–241. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12242

Goldberg, A. E., & Sweeney, K. K. (2019). LGBTQ parent families. In B. H. Fiese, M. Celano, K. Deater-Deckard, E. N. Jouriles, & M. A. Whisman (Eds.), APA handbooks in psychology®. APA handbook of contemporary family psychology: Foundations, methods, and contemporary issues across the lifespan (p. 743–760). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000099-041

Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond culture. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Kerr, M. E., & Bowen, M. (1988). Family evaluation: An approach based on Bowen theory. W W Norton & Co.

Klein, A., & Golub, S. A. (2016). Family Rejection as a Predictor of Suicide Attempts and Substance Misuse Among Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Adults. LGBT Health, 3(3), 193–199. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0111

Lareau, A., Marks, S. R., Bubriski, A., Curran, R., Frye, S. B., Pierce, C. A., … Gerstel, N. (2007). Famly Focus On Families and Social Class (pp. F1–F16). Minneapolis, MN: National Council on Family Relations.

Martin, C. L., & Ruble, D. N. (2010). Patterns of gender development. Annual review of psychology, 61, 353–381. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100511

N., Pam M.S., “FAMILY OF ORIGIN,” in PsychologyDictionary.org, May 11, 2013, https://psychologydictionary.org/family-of-origin/ (accessed January 16, 2020).

Olson, K. R., Durwood, L., DeMeules, M., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2016). Mental health of transgender children who are supported in their identities. Pediatrics. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3223.

Pettigrew, T. F. (1989). The nature of modern racism in the United States. Revue Internationale de Psychologie Sociale, 2(3), 291–303.

Race & Ethnicity. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://genderedinnovations.stanford.edu/terms/race.html

Rotimi, C. N. (2004). Are medical and nonmedical uses of large-scale genomic markers conflating genetics and race? Nature Genetics, 36(S11). doi: 10.1038/ng1439

Rovers, M. (2004). Family of Origin Theory, Attachment Theory and the Genogram. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy, 3(4), 43–63. doi: 10.1300/j398v03n04_03

Ryan, C., Huebner, D., Diaz, R. M., & Sanchez, J. (2009). Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics, 123(1), 346–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

Ryan, C., Russell, S. T., Huebner, D., Diaz, R., & Sanchez, J. (2010). Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 23(4), 205–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00246.x.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

Serwer, S. by A. (2019, March 14). White Nationalism’s Deep American Roots. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/04/adam-serwer-madison-grant-white-nationalism/583258/