3 Family of Origin Relationships: Culture, Religion, and Ethnicity

Family of Origin

Family-of-Origin (FoO) refers to the family that an individual was raised by and developed with. This may or may not include biological family in instances where adoption or separation occurred (PsychologyDictionary.org). Family-of-Origin is credited with much of a person’s early development, including norms and attitudes, and while it can be discussed in parallel with Attachment Theory, Martin Rovers (2004) identifies the distinct conceptual framework from which each approach has evolved.

More functionally, FoO is the group of people—parents, guardians, siblings, aunts/uncles, grandparents—that we learn from, from which we gain personal identity, who guide our concept of familial and societal norms, and who impart attitudinal values upon us. Much of our understanding of self and perceptions of the world are rooted in FoO. Genograms are a tool, much like a detailed family tree, which have been used in FoO therapy to map relationships in order to identify patterns of FoOs and their potential impact on an individual (Kerr & Bowen, 1988). These will be described in detail in Chapter 8.

Family-of-Origin is a complex unit which is composed of many intersecting identities including culture, religion, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation and class, amongst others. Here we will consider some of these dimensions and how they influence individual FoO experiences, making for a diverse outlook on life.

Culture

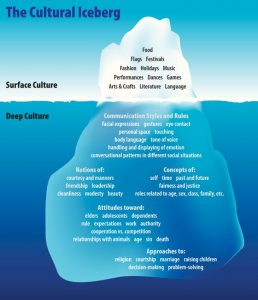

Culture is a concept that is made of many tangible and intangible things. So, what is it? Aspects of culture combine to influence our perspective of the world, including expectations of how the world works and what lies ahead of us in the future. Culture can be traditional practices, norms around behavior and humor, food, and attitudinal outlook. Culture can also be deep and intricate beliefs rooted in religion/spirituality, or about family development. Anthropologist Edward Hall produced the “Iceberg of Culture” analogy (Figure 1), which describes the conscious aspects of culture, available to us at a surface level, and subconscious aspects of culture which dwell beneath the surface of our societal awareness (Hall, 1976). While we often think of ways that cultural differences make us distinct from one another, we should also consider shared cultural aspects that make us alike. Culture has implications for society, but it also affects our FoO, and it is important that we reflect on how these cultural elements impact us in our FoO. We must also acknowledge that cross-cultural or intercultural FoO exist, that they have existed, and that they are continuing to exist as the world globalizes.

Points to Ponder:

- How does understanding culture of FoO affect me?

- What does family culture mean to me?

- What do I think family culture means in the westernized (North America, some of Europe) context? What about in the global context?

- How do I think societal culture affects family?

- Are there distinctions between societal culture and family culture?

- How have families evolved?

- Due to migration over time?

- Due to the advances in technology (methods of interpersonal communication)?

Religion

Religiosity and/or spirituality are intimate aspects of FoO. Religious ideologies and the practice of religion are highly influential in family function, traditions, norms, and may even have implications for family formation in some cases. As seen in the Catholic church, among many other religions, Catholic marriages take place within the Catholic church and if one partner in the relationship is not also Catholic, they often will convert to match their Catholic partner. These complex networks of beliefs, families, and community can be monumental within family practice. The contribution of religion to family culture may be as simple as attending worship together and determining what holidays are practiced. However, religiosity and spirituality are a spectrum. In other instances religion may inform every decision made within a family unit (e.g. gender norms, acceptability and appropriateness of behavior and dress, the food that is eaten, the daily schedule, what schools are attended, what media and cultural influences are preferred, intimacy of family relationships, religious vs. secular perspective on information, etc.). For some families, religion may be a unifying experience, while for others religious ideologies or practices may be points of contention and turmoil (Dollahite, Marks & Dalton, 2018). Religion can be a highly integrated aspect of identity, therefore, it is important that we consider its impact when FoO religious identity and the individual (one person within family) align or differentiate.

Points to Ponder:

- Do religion or spirituality play a role in my Family of Origin?

- What role does religion play in family formation? My own?

- What role does religion play in family values or practices (FoO culture)?

- What role does religion play in family conflict?

- What about family connection or family healing?

Race and Ethnicity

Race and ethnicity are complex terms that are often used interchangeably, though they imply very different things. The group Gendered Innovations from Stanford University briefly explains why these terms are different, and in fact, how they are socially constructed concepts (Race & Ethnicity, n.d.). In the past race was discussed as a biological factor with implications on health and beyond, even though past, present, and ongoing research does not support genetic differences of race (Bamshad, Wooding, Salisbury & Claiborne, 2004; Rotimi, 2004). Instead, differences in physical characteristics, like the increased melanin pigmentation of skin, become racial differences when societies attach meaning like social values, norms, expectations, and prejudices to these variations in skin color and other features. Similarly, ethnicity is the association of a person to group or culture that share “identity-based ancestry” (Race & Ethnicity, n.d.). Unfortunately, social judgement of physical features or “race-based” characteristics may predefine someone’s ethnicity to dominate culture (white or western) society, despite how that individual actually identifies themselves. In the TEDx Talk, “Let’s Talk About Race,” Jennifer Chernega recounts the story of a young person born in Norway to Somalian parents. Though this person identifies as Norwegian, Dr. Chernega tells us that they are not regarded as ethnically Norwegian within the only home country they’ve ever known.

So, with all of this in mind, what does race and/or ethnicity have to do with families? First, we must recognize that FoO is potentially one of the most intimate social networks within which we experience our personal identity, this includes racial and/or ethnic identities. Next we must recognize that children recognize physical characteristic differences. We should call to question what roles family and society play in helping young people understand race and breaking down prejudicial values which perpetuate racism. In his TEDx Talk, Anthony Peterson describes the dynamic of his multi-racial family, and speaks to the important learning process that happens between children and adults when families break down the walls of race instead of continuing silence around the subject.

Watch it here.

Peterson points out another important factor for us to consider with race, ethnicity and families, which is how we assume racial or ethnic differences in family dynamics or practices. As he points out familial norms/culture are not based on skin color, instead these are likely elements of other cultural norms or products of racial and ethnic social construction by larger society. Remember that culture can be an iceberg of factors, and family culture could be an intersection of historical culture, ancestral culture, regional culture (“Iowa Nice”), interpersonal culture, trauma culture, and others.

Within the United States, and globally, there is clear evidence of the impact that racism and nationalism has had on People of Color and non-Western groups (Pettigrew, 1989; Serwer, 2019 ). Racist and nationalist ideologies give way to prejudicial treatment of certain groups, which in turn creates disparities in health, socioeconomic status, environment, criminalization, class, education, and more. Family units are undoubtedly affected by these burdens on wellbeing, and it is vital that we acknowledge and work to deconstruct the structural prejudices that weigh more heavily on some families than others.

Points to Ponder:

- How is my racial or ethnic identity influenced by my family of origin?

- Does society predefine our racial and ethnic identities? If so, how?

- What elements of this are structural

- What can be done to change this?

- What can I do to change this?

- Why do we associate certain family norms with race rather than other elements of culture?

- Are these based on stereotypes?

- What important elements of family are diluted or forgotten if we associate family norms with race only (i.e. White families do this, Black families do that, Asian parents are like this, etc.)?

- How can we become more comfortable discussing race within our families?

What to know more?

Chatters, L. M., & Taylor, R. J. (2005). Religion and Families. In V. L. Bengtson, A. C. Acock, K. R. Allen, P. Dilworth-Anderson, & D. M. Klein (Eds.), Sourcebook of family theory & research (p. 517–541). Sage Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412990172.n21

Frame, M. W. (2000). The Spiritual Genogram In Family Therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 26(2), 211–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2000.tb00290.x

Framo, J. L. (2015). Family-of-origin therapy: an intergenerational approach. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hook, J. V., & Glick, J. E. (2020). Spanning Borders, Cultures, and Generations: A Decade of Research on Immigrant Families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 224–243. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12621

Kane, C. M., & Erdman, P. (1998). Differences in Family-of-Origin Perceptions among African American, Anglo-American, and Hispanic American College Students. The Family Journal, 6(1), 13–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480798061003

Soliz, J. (2007). Communicative Predictors of a Shared Family Identity: Comparison of Grandchildrens Perceptions of Family-of-Origin Grandparents and Stepgrandparents∗. Journal of Family Communication, 7(3), 177–194. doi: 10.1080/15267430701221636

Sutton, T. E. (2018). Review of Attachment Theory: Familial Predictors, Continuity and Change, and Intrapersonal and Relational Outcomes. Marriage & Family Review, 55(1), 1–22. doi: 10.1080/01494929.2018.1458001

Thomas, A. J. (1998). Understanding Culture and Worldview in Family Systems: Use of the Multicultural Genogram. The Family Journal, 6(1), 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480798061005

Timmons, A. C., Han, S. C., Chaspari, T., Kim, Y., Pettit, C., Narayanan, S., & Margolin, G. (2019). Family-of-origin aggression, dating aggression, and physiological stress reactivity in daily life. Physiology & Behavior, 206, 85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2019.03.020

TEDx Talks and Other Videos

Jennifer Chernega, “Let’s Talk About Race”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rf8q-8gbfrw

Baratunde Thurston, “How to deconstruct racism, one headline at a time”