Ketone Management

The presence of urine or blood ketones in a diabetic patient is an indication that there is significant insulin deficiency. Aggressive treatment of ketones with additional insulin is needed to prevent deterioration into diabetic ketoacidosis.

Ketones should be checked whenever blood glucose is >240mg/dL and whenever a patient is ill, even if blood sugars are normal.

How Are Ketones Checked?

Ketone monitoring in the inpatient setting is usually performed with:

- Urine ketone dipstick (on Levels 9, 10, and 11 of SFCH)

- Urinalysis (in ED or PICU)

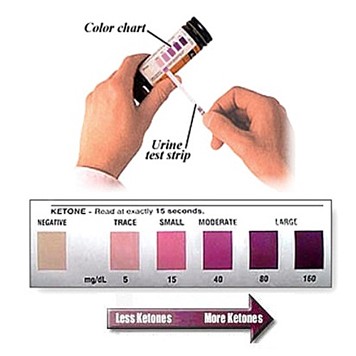

Urine ketone dipsticks are used by patients at home (Figure 1).

A urinalysis (UA) will report ketones as negative, +1, +2 and +3, corresponding to the negative, small, moderate, or large ketones, respectively. Alternatively, some labs report the quantity of ketones in mg/dL for which: <5 = trace to negative, 15 = small, 40 = moderate, >80 = large.

Urine ketone tests detect acetoacetate (rather than beta-hydroxybutyrate) and represent average urine ketone concentration since the last void. Thus, these are not the perfect method for accurately tracking ketones, as urine ketones may lag behind the development of mild ketonemia leading to delays in initiation ketone management. Conversely, the lag may also falsely represent ketonemia that has since resolved.

In severely dehydrated patients with low urine output, relying on UAs or ketone strips can delay initiating much-needed ketone corrections.

Despite these pitfalls, urine ketone monitoring is significantly cheaper, painless, and requires little in the way of supplies or technical skills training. Therefore, it is the preferred method for home ketone monitoring and is emulated during inpatient admission.

Serum beta-hydroxybutyrate levels can be sent to evaluate for ketones in the blood and is a much more accurate method for real-time ketone quantification. These can be useful in the inpatient setting when patients are not routinely voiding, are severely dehydrated, or if urine ketone results seem discrepant from the patient’s clinical status. In the outpatient setting, some patients will have blood ketone meters that can be used to check blood ketones at home. However, we do not use these home ketone meters in the inpatient setting.

Ketone correction boluses of rapid-acting insulin injections are given every 3 hours to shut down ketone production.

These are relatively large insulin doses, representing 10% to 20% of an individual’s total daily insulin dose requirement (TDD). Therefore, it is important to ensure blood sugar is >240mg/dL before treatment to avoid subsequent hypoglycemia. Usually, this is not a problem, as patients are generally more insulin resistant when ketones are present.

Because we rely on urine ketones monitoring, if a patient cannot void by the next three hours, it should be assumed that ketones are present at the level previously tested and treated as such.

USE THE KETONE/HYPERGLYCEMIA DECISION TREE TO HELP GUIDE MANAGEMENT from the Insulin Administration Chapter.

Inpatient Ketone Management Example:

Insulin Regimen: TDD: 20 units, I:C of 1:10 (all meals), Hyperglycemia correction (HC) of 1:50 > 150

The above chart represents a clinical scenario of a patient who has Large ketones at breakfast and is treated to clear ketones throughout the day.

The above chart represents a clinical scenario of a patient who has Large ketones at breakfast and is treated to clear ketones throughout the day.

Prior to breakfast, as the blood glucose is <240mg/dL, 15g of rapid-acting carbs (juice) are given and blood glucose is checked 15-20 minutes later. Now the blood glucose is >240mg/dL and the patient is going to eat breakfast, so mealtime insulin (CC) and the additional ketone correction are given (10 units total of rapid-acting insulin).

The next blood glucose is a scheduled 2-hr post-prandial blood glucose. Another ketone check and correction is not due until 1100 (3 hours after initial ketone correction). The patient urinates at 1030 and has moderate ketones. 15g of juice is provided at this time, as the previous blood glucose was down-trending and <240mg/dL. The blood glucose at 1100 shows BG is 270mg/dL, so 2 units of ketone correction are given for the treatment of moderate ketones.

The patient then prepares to eat lunch at 1230. As a ketone correction was given in the preceding 3 hours, additional correction insulin cannot be given, so only mealtime insulin for carbohydrate coverage is provided at this time.

You ask the nurse to encourage the patient to urinate at the 2-hour post-prandial glucose check which shows small ketones. Although he is due for another ketone correction, the juice must be given to boost blood glucose to >240mg/dL, so you give 30g of juice and find blood glucose improved 15 minutes later to 210mg/dL. As the blood glucose is not >240mg/dL, you ask the patient to drink another 15g of juice. At this point, you can assume the blood glucose will rise to >240mg/dL with this additional treatment and give the 2 units of ketone correction for treatment of small ketones to avoid further delays in treatment.

3 hours later the patient is ready for dinner, however, our patient won’t urinate. At this point, you should assume the patient still has small urine ketones (unless you send a STAT serum Beta-hydroxybutyrate). Because you don’t want to keep the patient from eating, you presumptively treat for small ketones with his meal. 15g of juice was given before eating the meal to provide “uncovered carbs” since blood glucose is not >240mg/dL.

The 2-hr post-prandial dinner glucose is 90mg/dL and your patient’s ketones are now trace! You encourage your patient to drink water to promote continued clearance of ketones and ask for the patient to void around midnight to ensure ketones are remaining trace or negative.

Once ketones are trace or negative x 2 consecutive checks, additional ketone checks are only needed if blood glucose is >240mg/dL. In this case, the patient’s BG check at 0300 is 283mg/dL, so you have him recheck ketones which are still negative, so instead, you give a hyperglycemia correction and ask the nurse to check a blood glucose 2 hours later at 0500 before his next routine blood glucose before breakfast.

Manage A Simulated Patient!

Click the following link (https://slimgec.github.io/ds1/) to access a diabetes ketosis simulator produced by Dr. Catherina Pinnaro.

This simulator will first give you a patient scenario and ask you to calculate an initial insulin regimen. It will then ask you to manage this patient’s ketones and hyperglycemia until they have cleared. The simulator will provide feedback on your performance; the same scenario can be repeated as often as desired.

Dr. Norris’s article, “The Most Common Cognitive Error that Physicians Make When Treatment Patients with Type 1 Diabetes”, (2020), expertly explains a common cognitive error in managing a patient with diabetes who is NPO. This error is withholding dextrose-containing fluids.

In this article, Dr. Norris uses an analogy to compare the metabolic processes that occur during the omission of the IV dextrose to cutting the fuel to the engine of the plane and the pilot letting go of the stick.

….it is poor practice to allow patients with diabetes to develop diabetic ketoacidosis while admitted! So take a moment to read the short article and discover why the provision of dextrose is necessary for our diabetes patients who are NPO!

Bibliography:

- Pinnaro, C., Christensen, G. E., & Curtis, V. (2021). Modeling Ketogenesis for Use in Pediatric Diabetes Simulation. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology, 15(2), 303-308. doi:10.1177/1932296819882058

- Norris, A. (2022, February 3). The most common cognitive error that physicians make when treating patients with type 1 diabetes. News & Views From the Division Director: University of Iowa Stead Family Children’s Hospital. https://pendia.peds.uiowa.edu/2020/06/type-1-diabetes-inpatient-management/

Figures:

- Figure 2: Figure 2 was created by Dr. Alex Tuttle using a compilation of the following icons: “Crash icon” by pongsakornRed and “Fasting icons” by Freepik, both found at Flaticon.com

Feedback/Errata