Long-Acting Insulins

Lantus (glargine) is a recombinant human insulin analog.

It is preferred long-acting insulin on the Stead Family Children’s Hospital’s inpatient formulary.

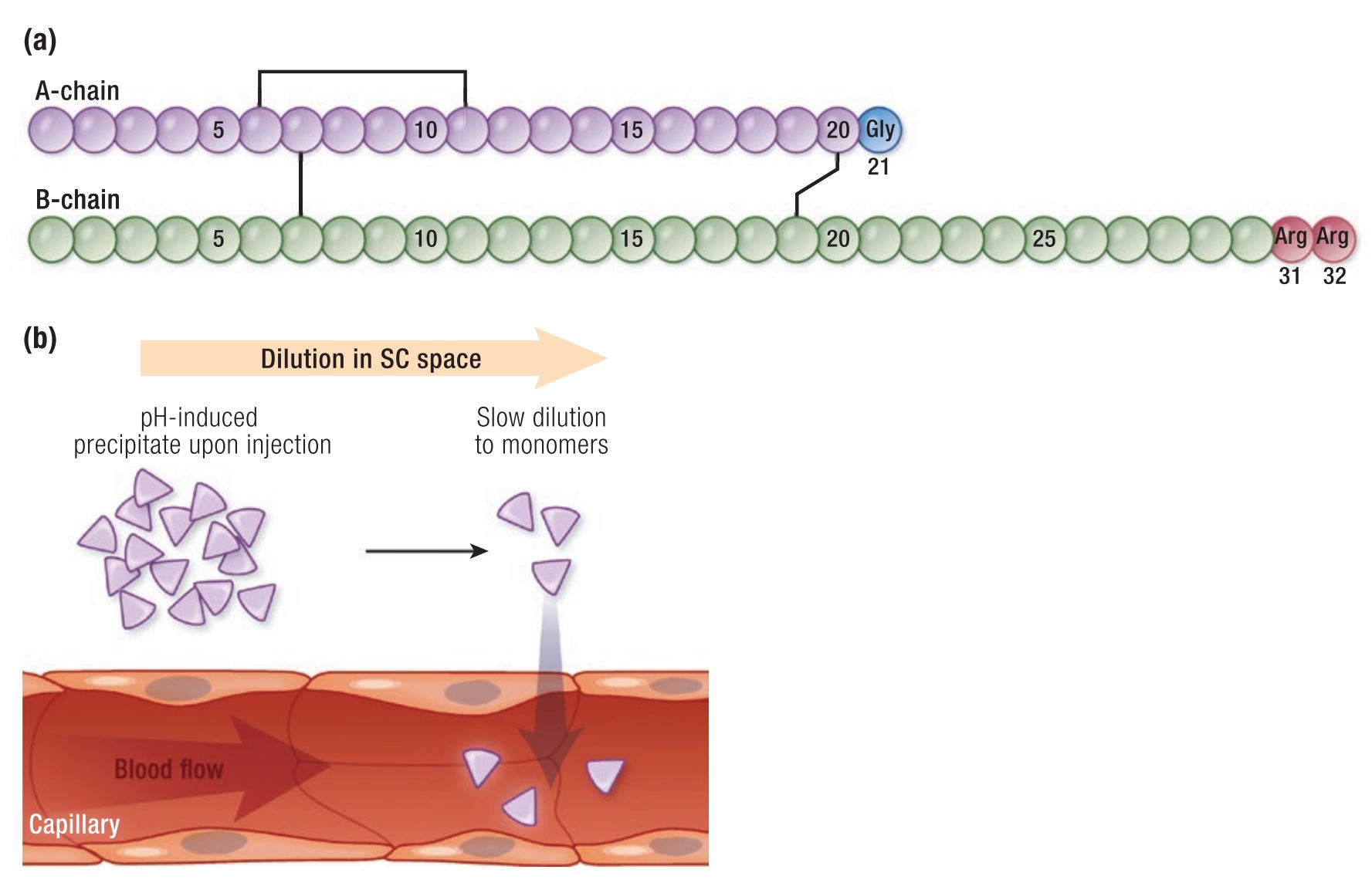

Lantus works as a long-acting insulin because after its injection into the subcutaneous tissue, the acidic solution (pH 4) in which the insulin is dissolved is rapidly neutralized. This leads to the formation of microprecipitates from which small amounts of insulin monomers are slowly released (Figure 1), resulting in a relatively constant concentration/time profile over 24 hours with no pronounced peak.

Long-acting insulins are usually dosed once in the morning or before bedtime and given around the same time each day.

Most long-acting insulins are considered “peakless” insulins as they have a gradual onset, usually within a few hours after administration, and have a long duration of action. They are ideal when used as part of a basal/bolus insulin regimen involving multiple daily injections or with inhaled insulin.

As long-acting insulin comprises about 50% of the total daily insulin needs, there is almost never a reason that long-acting insulin doses should be held or not administered.

As long-acting insulin comprises about 50% of the total daily insulin needs, there is almost never a reason that long-acting insulin doses should be held or not administered.

- Dose reductions may need to be considered prior to planned major surgical procedures.

A common mistake made by less experienced providers or patients is holding long-acting insulin if:

- A patient is sick and has a significantly decreased appetite

- The blood glucose is low around the time the long-acting insulin is usually given.

Patients who are ill produce stress hormones and have increased sympathetic tone. This, more often than not, leads to hyperglycemia and an increased risk of ketosis. By not giving the long-acting insulin, the relative insulin deficiency makes hyperglycemia worse and can make the patient enter into DKA.

Acute hypoglycemia is usually due to an error in the dosing of the rapid-acting insulin or recent exercise. Patients should treat their hypoglycemia and then take their long-acting insulin if it is due. A decrease in the long-acting insulin dose may need to be considered if a patient is struggling with recurrent hypoglycemia throughout the day, however, even then, the dose should never be held entirely.

In the outpatient setting, there are many other types of long-acting insulin that patients may be using.

In the outpatient setting, there are many other types of long-acting insulin that patients may be using.

It is important to recognize when patients are on these other types of long-acting insulin, as:

- Different concentrations of long-acting insulins exist

- Conversion to Lantus may not be a “one to one” conversion

- Biosimilar/analogs of Lantus including Basaglar and Semglee are a 1:1 conversion.

- Examples of Long-acting insulins that are not always a 1:1 conversion include:

-

Quiz Yourself:

Bibliography:

- Hirsch IB, Juneja R, Beals JM, Antalis CJ, Wright EE. The Evolution of Insulin and How it Informs Therapy and Treatment Choices. Endocr Rev. 2020 Oct 1;41(5):733–55. doi: 10.1210/endrev/bnaa015. PMID: 32396624; PMCID: PMC7366348.

Feedback/Errata