Type 2 Diabetes

The incidence of Type 2 diabetes in youth in the US is rising, disproportionately more so in certain minority populations. Data also indicates a slight female predominance.

Note that the overall incidence of T2DM is lower than T1DM, so it is still more likely that a pediatric patient <20 years old with new-onset diabetes has T1DM.

- According to the SEARCH trial, the incidence of Type 2 diabetes from 2002 to 2012 increased by 7.1% overall = 9 per 100,000 in 2002-2003 to 13.8 per 100,000 in 2014-2015.

- An increase in incidence rate was seen in all age, sex, and race/ethnicity groups except the non-Hispanic white population

- The highest rate of change in incidence rates (AKA annual percent change) was observed in Asians or Pacific Islanders (7.7%) followed by Hispanics (6.5%), and non-Hispanic Blacks.

- Patients of American Indian ethnicity are more likely to present with Type 2 diabetes rather than Type 1 diabetes.

- A recent cross-sectional, multicenter prevalence study by Lawrence et al. (2021) showed that the prevalence of Type 2 diabetes has almost doubled in 10–19-year-olds from 0.34 to 0.67 per 1000 youths in 2001 and 2017 respectively.

- The greatest change in prevalence was again seen in non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanic youths.

While obesity prevalence rates have been associated with increased rates of Type 2 diabetes in all population groups, it is likely not the only explanation for the changes in incidence and prevalence seen in minority populations. Rather, this may represent genetic susceptibility toward insulin resistance. This is likely why a strong family history of T2DM is often seen among affected youths.

- 45-80% have at least one parent with DM and 74-100% have a first- or second-degree relative with T2DM.

Risk factors contributing to T2DM include:

- Increasing weight, rate of weight gain, BMI, waist-to-hip ratio, and central fat distribution

- Genetic background (ethnicity/race and other family genetics)

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Being small OR large for gestational age

- Being an infant of a diabetic mother

- Lack of (or shortened duration) of exclusive breastfeeding as an infant

Type 2 diabetes is caused by a combination of insulin resistance and the inability of the pancreatic β-cells to compensate with sufficient insulin secretion.

Type 2 diabetes is rarely seen in pre-pubertal children under ten years of age.

- Pubertal children have a natural, intrinsic increase in insulin resistance due to increased sex steroid production. Most children can compensate for this increased resistance by increasing β-cell insulin production.

- For those who are unable to compensate, a relative insulin deficiency develops.

- The addition of obesity, other risk factors, and genetic background can tip the scales even further and lead to the eventual emergence of clinical Type 2 diabetes.

Insulin resistance occurs mostly at the liver, muscle, and adipose tissue level, leading to metabolic derangements in glucose, protein, and lipid metabolism. This, in turn, causes vascular endothelial dysfunction leading to micro-and macro-vascular complications that occur earlier than in Type 1 diabetes.

The Figure below shows the relationship between how insulin secretion changes as insulin resistance increases, leading to Type 2 diabetes. Explore the graph below for further information!

In some cases, patients who have an initial response to non-insulin medications that improve insulin secretion and/or insulin sensitivity may develop irreversible β-cell insulin secretory failure. These patients then become dependent on exogenous insulin replacement.

Children with Type 2 diabetes can present on a spectrum ranging from acute manifestations of symptoms overlapping with Type 1 diabetes (the polys and weight loss) to mild hyperglycemia noted incidentally.

- Up to 50% may be asymptomatic.

- While presentation in DKA is less common in Type 2 diabetes, it does occur in up to 10% of children with new-onset T2DM.

- Over 90% of children with Type 2 diabetes are overweight (BMI greater than the 85th percentile) or obese (BMI greater than the 95th percentile).

- Hypertension, skin infections, yeast infections, and acanthosis nigricans may be present on the exam

- Acanthosis nigricans is common (60-95% of patients), but not always present.

After meeting the diagnostic criteria for diabetes, second-tier laboratory testing should be obtained to further distinguish between Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes.

Children with Type 2 diabetes are more likely to present with earlier and severe complications of obesity and diabetes at the time of diagnosis when compared with Type 1 diabetes.

Therefore, screening for retinopathy, dyslipidemia, hypertension, microalbuminuria, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NASH) is necessary at the time of (or soon after) diagnosis.

Laboratory results that help define the diagnosis of Type 2 diabetes include:

- Elevated levels of:

- C-peptide (the endogenous cleavage product of pro-insulin, secreted in a 1:1 ratio upon insulin release)

- Total insulin (a measure of endogenous insulin)

- AST/ALT (if persistently elevated, these may be due to the presence of NASH)

- Cholesterol and/or Triglycerides (dyslipidemia)

- Urine microalbumin (persistently elevated levels may indicate early nephropathy)

- Negative (or few) Islet/β-cell autoimmune antibodies:

- At the University of Iowa, we often send GAD, IA-2, anti-Insulin, and anti-Islet cell autoantibodies for almost all patients with new-onset diabetes if there is any doubt about the diagnosis between Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes. However, as discussed previously, the following autoantibodies may be present in T2DM and also portend the future need for exogenous insulin therapy:

- Glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies (GAD Ab)

- IA-2 Antibodies

- At the University of Iowa, we often send GAD, IA-2, anti-Insulin, and anti-Islet cell autoantibodies for almost all patients with new-onset diabetes if there is any doubt about the diagnosis between Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes. However, as discussed previously, the following autoantibodies may be present in T2DM and also portend the future need for exogenous insulin therapy:

While laboratory tests can be helpful, they sometimes do not provide a definitive diagnosis of Type 1 vs. Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Often the definitive diagnosis becomes clearer over time, and if it does not, may prompt endocrinologists to consider other forms of diabetes mellitus.

The same multidisciplinary team of healthcare providers for patients with Type 1 diabetes (link) is necessary for the treatment of children with T2DM.

The goals of treatment for T2DM differ from T1DM and involve:

- Normalizing glycemia with target HbA1c of less than 6.5% without excessive hypoglycemia

- Education about healthy lifestyle changes in diet and activity aimed at promoting healthy weight loss.

- Prevention or control of associated comorbidities (dyslipidemia, hypertension, nephropathy, hepatic steatosis, sleep apnea, and mental health concerns)

The cornerstone of T2DM therapy is behavioral and lifestyle modification.

Pharmacotherapy:

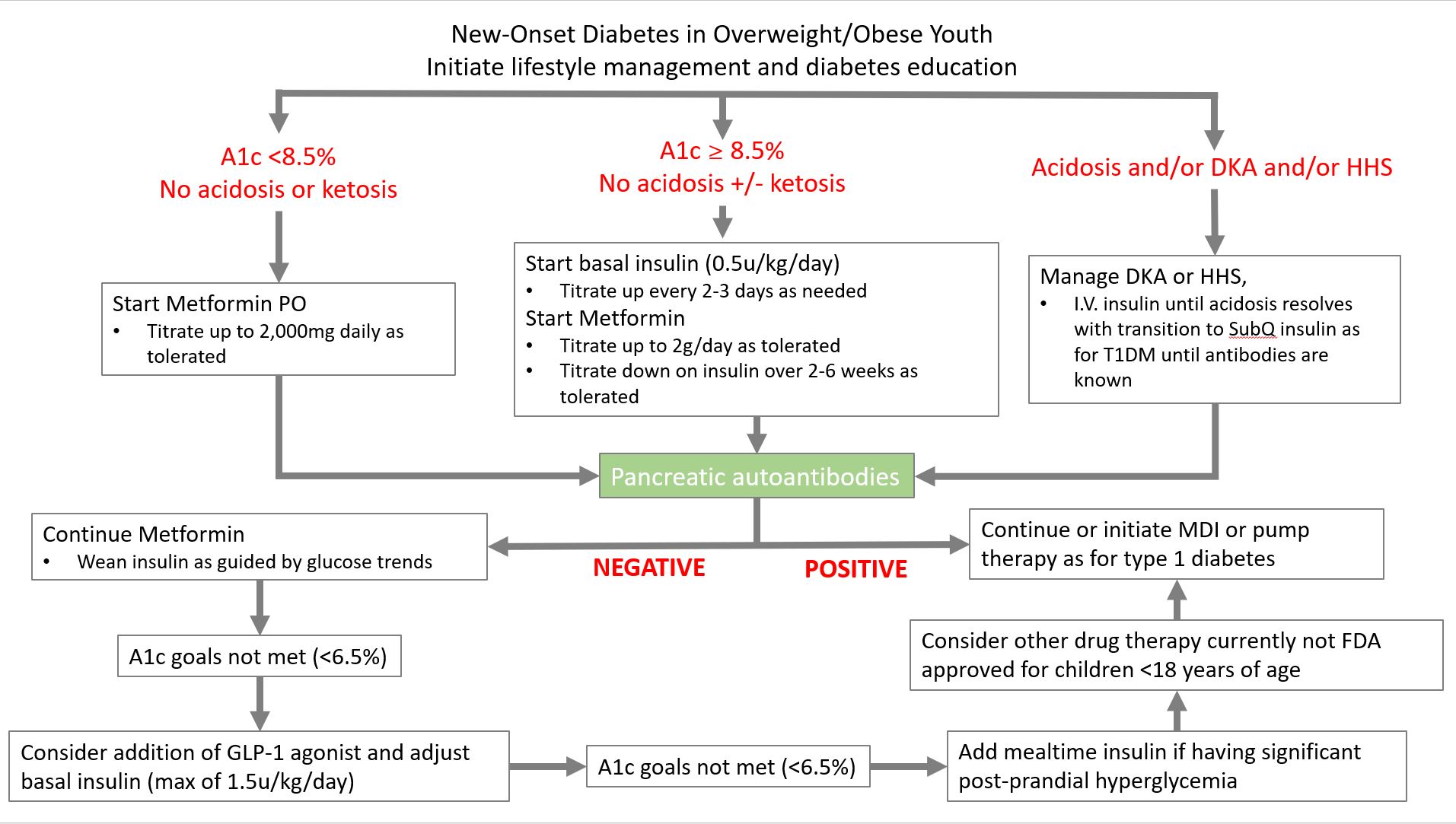

Initial pharmacotherapy is guided by the presenting severity of the patient’s metabolic status as seen in Figure 3.

- Until 2018, the only medications approved for treating type 2 diabetes in children included metformin and insulin.

- There are other oral and injectable anti-diabetes medications approved for treating Type 2 diabetes in adults, but as with all pediatric pharmacologic trials, approval of these medications for use in children is generally significantly delayed.

- In the last few years (2019 – 2023), GLP-1 agonist therapies have become FDA-approved for treating Type 2 diabetes in children. These include:

- Liraglutide (Victoza)

- Extended-release Exenatide

Pramlintide, SGLT2 inhibitors, DPP-4 inhibitors, and some other adult-FDA-approved antidiabetes medications can be considered if there is a failure to achieve sufficient glycemic control with metformin and GLP-1 agonist therapy. The selection of these additional therapies in adults is guided by the presence of other complications of diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Quiz Yourself:

Bibliography:

- Arslanian S, Bacha F, Grey M, Marcus MD, White NH, Zeitler P. Evaluation and Management of Youth-Onset Type 2 Diabetes: A Position Statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2018 Dec;41(12):2648-2668. doi: 10.2337/dci18-0052. PMID: 30425094; PMCID: PMC7732108.

-

Chen, M.E., Aguirre, R.S. & Hannon, T.S. Methods for Measuring Risk for Type 2 Diabetes in Youth: the Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT). Curr Diab Rep 18, 51 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-018-1023-3

- Lawrence, J. M., Divers, J., Isom, S., Saydah, S., Imperatore, G., Pihoker, C., . . . Liese, A. D. (2021). Trends in Prevalence of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes in Children and Adolescents in the US, 2001-2017. JAMA, 326(8), 717-727. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.11165

- Shah AS, Zeitler PS, Wong J, Pena AS, Wicklow B, Arslanian S, Chang N, Fu J, Dabadghao P, Pinhas-Hamiel O, Urakami T, Craig ME. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2022: Type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes. 2022 Nov;23(7):872-902. doi: 10.1111/pedi.13409. Epub 2022 Sep 25. PMID: 36161685.

Feedback/Errata